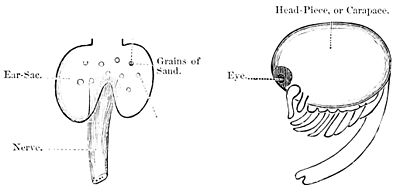

called the coral. The baby-lobsters differ greatly from their parents. Their eyes are very large, and set in the head instead of on eye-stalks. They have a great rounded head-shield (carapace) and a small body (Fig. 31). The limbs are not at all like the lobster's; altogether, he looks as if his eyes and head were running away with him. As soon as he is hatched he begins to swim about and feed himself, and never

| |

| Fig. 30. | Fig. 31.—Young Lobster. |

goes back to the old home. Of course, as he grows, his shell gets too small, but, instead of putting on an addition as the mussel does, he leaves the old house altogether and builds a new one. In three days after the lobster moves out of the old house he has been found all settled in a bran-new one one-third larger. Two round balls are often found in the lobster's stomach, and people call them "crab's-eyes." These balls are made of lime, which it is said the lobster has been storing up for his new shell. Thus the lobster moves "out of the old house into the new" every year till he gets his growth. Then he lives contentedly under the same roof till he dies, or till some one throws him into a lobster-pot.

| THE ELECTRICAL GIRL. |

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH OF LOUIS FIGUIER, BY CLARA HAMMOND.

IN the beginning of 1846, a year memorable in the history of table-turning and spirit-rapping, Angélique Cottin was a girl of fourteen, living in the village of Bouvigny, near La Perrière, department of Orne, France. She was of low stature, but of robust frame, and apathetic to an extraordinary degree both in body and mind. On January 15th of the year named, while the girl was with three others engaged in weaving silk-thread gloves, the oaken table at which they worked began to move and change position. The work-women were alarmed; work was for a moment suspended, but was soon resumed. But, when Angélique again took her place, the table began anew to