then be seen turned round, with its tip and the margin of the membrane pressed against the stomach, forming a capital trap, holding the fly, the captor remaining on his back till he had withdrawn the fly from the bag.

"I had no opportunity of observing the action when the bat was in full flight; but, if the insect was captured a few inches from the side of the cage, the mode was the same! When flying, the interfemoral

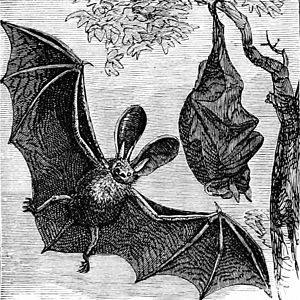

Fig. 2.—Long-eared English Bat (Plecotus auritus).

membrane is not extended to a flat surface (and appears not capable of being so stretched), but always preserves a more or less concave form, highly calculated to serve the purposes of a skim-net to capture insects on the wins.

"Occasionally, when the bat was sleepy, sitting at the bottom of the cage, nodding his head, a poor, silly 'blue-bottle fly,' no doubt of tender age, and not read in the natural history of the Vespertilionidæ, with the greatest confidence walked quietly under the bat, passing nose, ear, and eyes, without danger; but, immediately he touched the sensitive membrane of the bag, it was closed upon him, and there was no retreat except by being helped out of the difficulty by the teeth of the bat.

"I was much entertained last summer with a tame bat which would take flies out of a person's hand. If you gave it any thing to eat, it brought its wings round before the mouth, hovering and hiding its head in the manner of birds of prey when they feed. The adroitness it showed in shearing off the wings of the flies, which were always rejected, was worthy of observation, and pleased me much. Insects seemed to be most acceptable, though it did not refuse raw flesh when offered. ... I saw it several times confute the vulgar opinion that