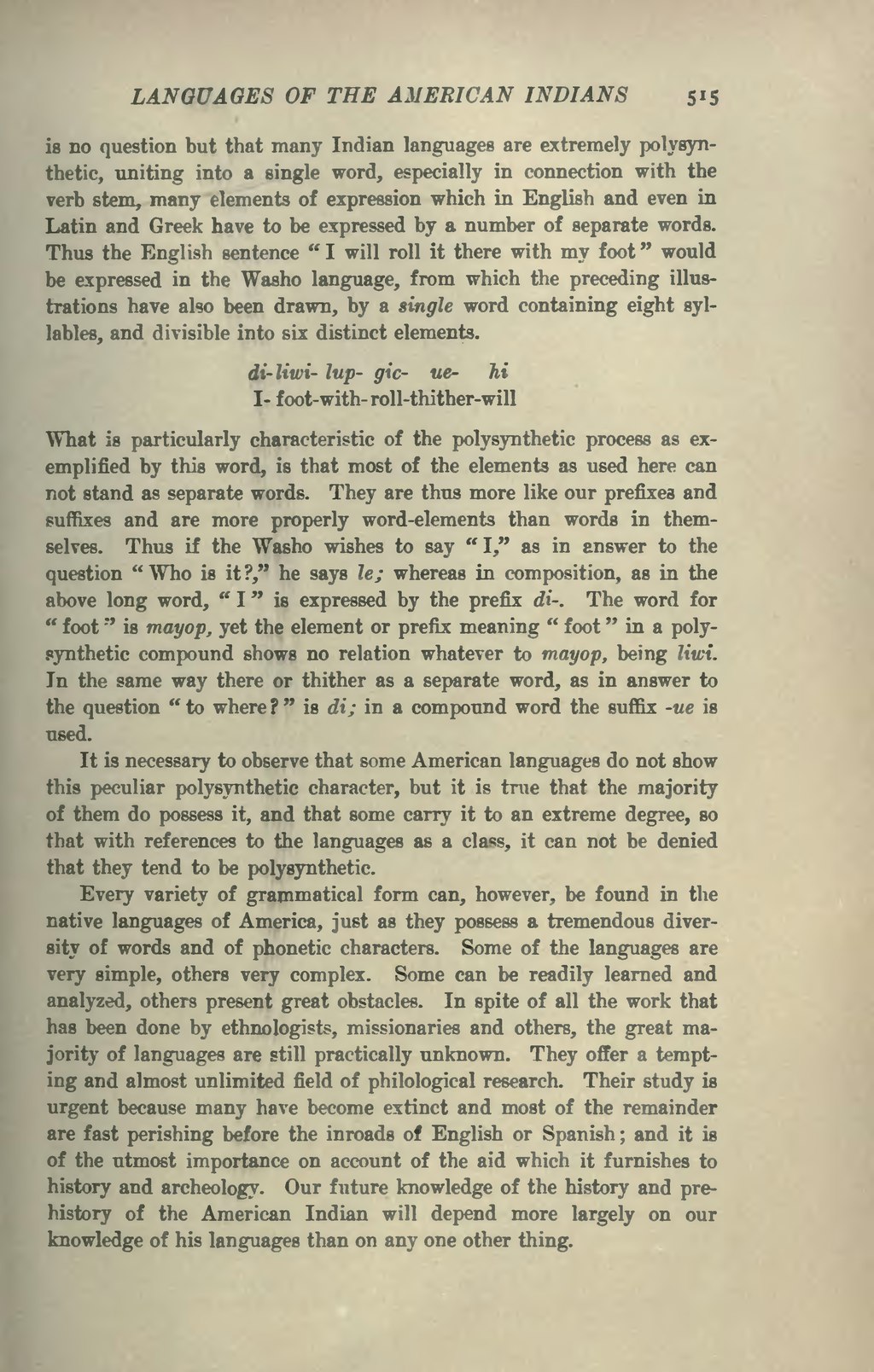

is no question but that many Indian languages are extremely polysynthetic, uniting into a single word, especially in connection with the verb stem, many elements of expression which in English and even in Latin and Greek have to be expressed by a number of separate words. Thus the English sentence "I will roll it there with my foot" would be expressed in the Washo language, from which the preceding illustrations have also been drawn, by a single word containing eight syllables, and divisible into six distinct elements.

di-liwi- lup- gic- ue- hi

I- foot-with-roll-thither-will

What is particularly characteristic of the polysynthetic process as exemplified by this word, is that most of the elements as used here can not stand as separate words. They are thus more like our prefixes and suffixes and are more properly word-elements than words in themselves. Thus if the Washo wishes to say "I," as in answer to the question "Who is it?," he says le; whereas in composition, as in the above long word, "I" is expressed by the prefix di-. The word for "foot" is mayop, yet the element or prefix meaning "foot" in a polysynthetic compound shows no relation whatever to mayop, being liwi. In the same way there or thither as a separate word, as in answer to the question "to where?" is di; in a compound word the suffix -ue is used.

It is necessary to observe that some American languages do not show this peculiar polysynthetic character, but it is true that the majority of them do possess it, and that some carry it to an extreme degree, so that with references to the languages as a class, it can not be denied that they tend to be polysynthetic.

Every variety of grammatical form can, however, be found in the native languages of America, just as they possess a tremendous diversity of words and of phonetic characters. Some of the languages are very simple, others very complex. Some can be readily learned and analyzed, others present great obstacles. In spite of all the work that has been done by ethnologists, missionaries and others, the great majority of languages are still practically unknown. They offer a tempting and almost unlimited field of philological research. Their study is urgent because many have become extinct and most of the remainder are fast perishing before the inroads of English or Spanish; and it is of the utmost importance on account of the aid which it furnishes to history and archeology. Our future knowledge of the history and prehistory of the American Indian will depend more largely on our knowledge of his languages than on any one other thing.