marsupial bone, and thence stretches itself over the inner or deep surface of the adjacent mammary gland or "breast," which is situated low down, and not in the breast at all.

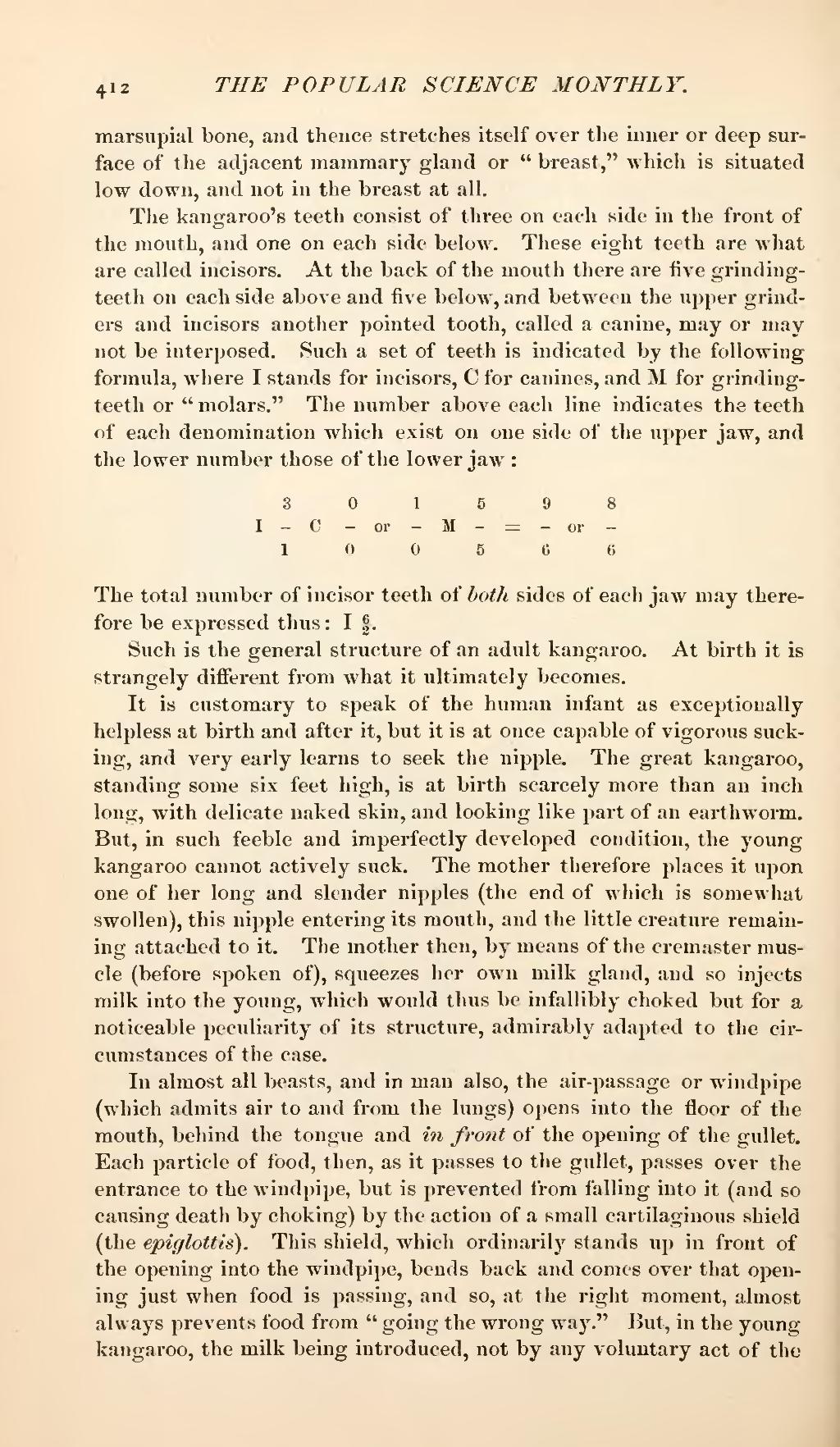

The kangaroo's teeth consist of three on each side in the front of the mouth, and one on each side below. These eight teeth are what are called incisors. At the back of the mouth there are live grinding-teeth on each side above and five below, and between the upper grinders and incisors another pointed tooth, called a canine, may or may not be interposed. Such a set of teeth is indicated by the following formula, where I stands for incisors, C for canines, and M for grinding-teeth or "molars." The number above each line indicates the teeth of each denomination which exist on one side of the upper jaw, and the lower number those of the lower jaw:

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 8 | ||||||

| I | — | C | — | or | — | M | — | = | — | or | — |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

The total number of incisor teeth of both sides of each jaw may therefore be expressed thus: I 6⁄2.

Such is the general structure of an adult kangaroo. At birth it is strangely different from what it ultimately becomes.

It is customary to speak of the human infant as exceptionally helpless at birth and after it, but it is at once capable of vigorous sucking, and very early learns to seek the nipple. The great kangaroo, standing some six feet high, is at birth scarcely more than an inch long, with delicate naked skin, and looking like part of an earthworm. But, in such feeble and imperfectly developed condition, the young-kangaroo cannot actively suck. The mother therefore places it upon one of her long and slender nipples (the end of which is somewhat swollen), this nipple entering its mouth, and the little creature remaining attached to it. The mother then, by means of the cremaster muscle (before spoken of), squeezes her own milk gland, and so injects milk into the young, which would thus be infallibly choked but for a noticeable peculiarity of its structure, admirably adapted to the circumstances of the case.

In almost all beasts, and in man also, the air-passage or windpipe (which admits air to and from the lungs) opens into the floor of the mouth, behind the tongue and in front of the opening of the gullet. Each particle of food, then, as it passes to the gullet, passes over the entrance to the windpipe, but is prevented from falling into it (and so causing death by choking) by the action of a small cartilaginous shield (the epiglottis). This shield, which ordinarily stands up in front of the opening into the windpipe, bends back and comes over that opening just when food is passing, and so, at the right moment, almost always prevents food from "going the wrong way." But, in the young kangaroo, the milk being introduced, not by any voluntary act of the