hole has been encountered, when of course, there is nothing of the kind. Indeed such cascades should be entirely harmless so long as the aeronaut keeps his machine well above the surface and therefore out of the treacherous eddies, presently to be discussed.

Wind Layers

It is a common thing to see two or more layers of clouds moving in different directions and at different velocities. Judgment of both the actual and the relative velocities of the cloud layers may be badly in error—the lower seems to be moving faster, and the higher slower, than is actually the case. Accurate measurements, however, are possible and have often been made.

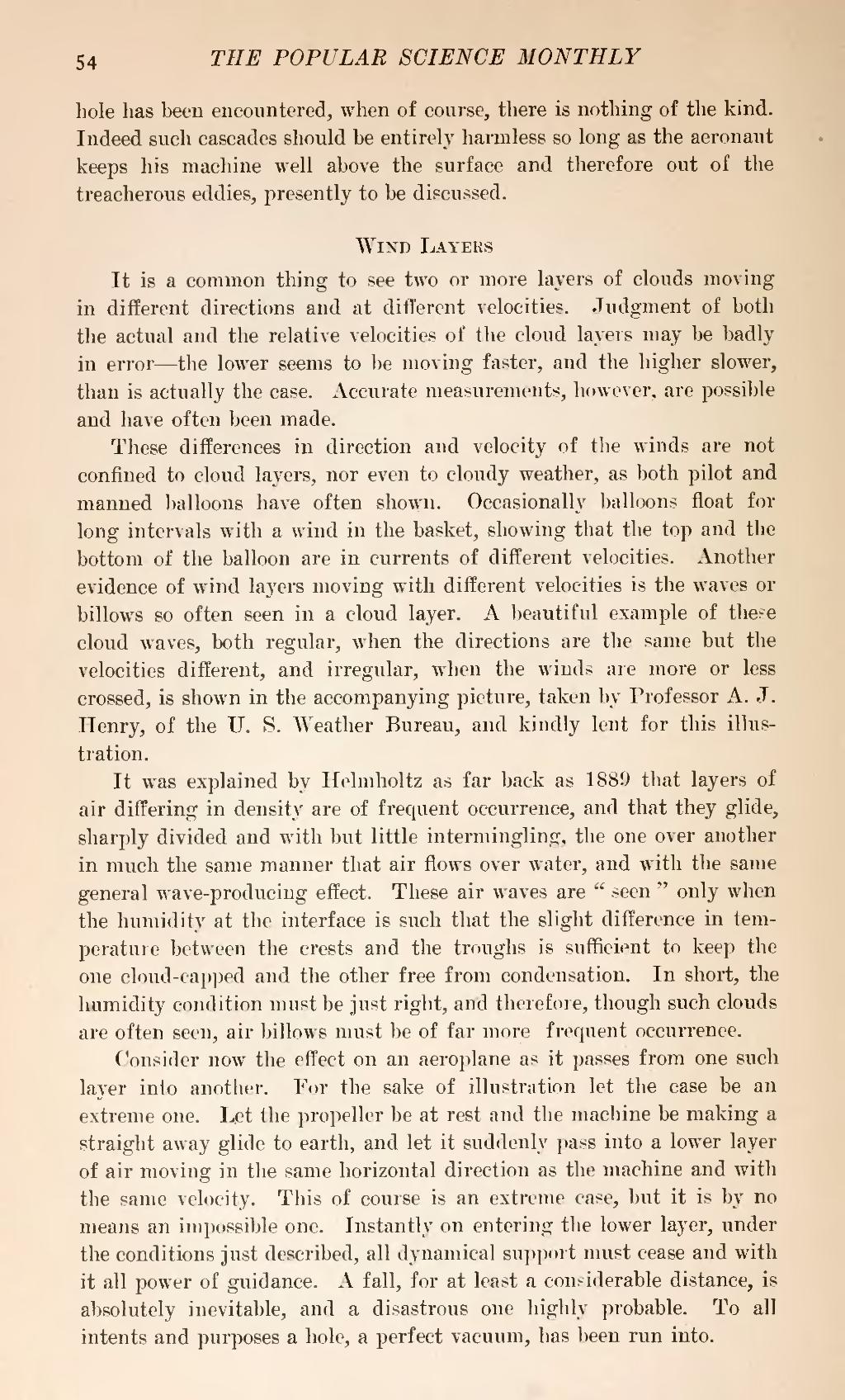

These differences in direction and velocity of the winds are not confined to cloud layers, nor even to cloudy weather, as both pilot and manned balloons have often shown-Occasionally balloons float for long intervals with a wind in the basket, showing that the top and the bottom of the balloon are in currents of different velocities. Another evidence of wind layers moving with different velocities is the waves or billows so often seen in a cloud layer. A beautiful example of the?e cloud waves, both regular, when the directions are the same but the velocities different, and irregular, when the winds are more or less crossed, is shown in the accompanying picture, taken by Professor A. J. Henry, of the U. S. Weather Bureau, and kindly lent for this illustration.

It was explained by Helmholtz as far back as 1889 that layers of air differing in density are of frequent occurrence, and that they glide, sharply divided and with but little intermingling, the one over another in much the same manner that air flows over water, and with the same general wave-producing effect. These air waves are "seen" only when the humidity at the interface is such that the slight difference in temperature between the crests and the troughs is sufficient to keep the one cloud-capped and the other free from condensation. In short, the humidity condition must be just right, and therefore, though such clouds are often seen, air billows must be of far more frequent occurrence.

Consider now the effect on an aeroplane as it passes from one such layer into another. For the sake of illustration let the case be an extreme one. Let the propeller be at rest and the machine be making a straight away glide to earth, and let it suddenly pass into a lower layer of air moving in the same horizontal direction as the machine and with the same velocity. This of course is an extreme case, but it is by no means an impossible one. Instantly on entering the lower layer, under the conditions just described, all dynamical support must cease and with it all power of guidance. A fall, for at least a considerable distance, is absolutely inevitable, and a disastrous one highly probable. To all intents and purposes a hole, a perfect vacuum, has been run into.