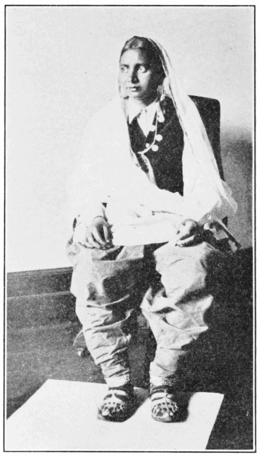

A Genuine Harem Skirt.

A Genuine Harem Skirt.

photograph, taken at Ellis Island, of a woman from Hindustan. good ship sailed, and their brilliant cheeks and country dress are in keeping with their dense ignorance and shyness. They know the price of shoes and what spuds are worth at market, but it is beyond them to recall the date of their birthday, or what the present month may be.

Those immigrants who are destined for points other than New York City are sent to the railroad room. Here they change their money for United States coin, and buy their railroad tickets under careful supervision. Their baggage is checked,  A Servian Woman. they have a telegraph, cable and post office of their own, and may buy lunches whose contents are exhibited to all in glass cases. Special agents see that each one buys a lunch proportioned to the size of his family and the length of his journey. Cigars, cakes and fruits are also to be had. One day a stolid and emotionless Slavish woman opened her cardboard lunch box at the bottom and extraced a piece of bologna cut on the bias, smelled it carefully from different sides, licked it, finally tasted it, and then broke into a flood of smiles as she pressed it forcibly into the mouth of her equally stolid two-year-old baby. And the baby sucked and munched on the new

A Servian Woman. they have a telegraph, cable and post office of their own, and may buy lunches whose contents are exhibited to all in glass cases. Special agents see that each one buys a lunch proportioned to the size of his family and the length of his journey. Cigars, cakes and fruits are also to be had. One day a stolid and emotionless Slavish woman opened her cardboard lunch box at the bottom and extraced a piece of bologna cut on the bias, smelled it carefully from different sides, licked it, finally tasted it, and then broke into a flood of smiles as she pressed it forcibly into the mouth of her equally stolid two-year-old baby. And the baby sucked and munched on the new