and-down motion, enabling certain of the teeth to cut meat as nippers do. There is also a backward-and-forward motion, producing a saw or file like operation, and there is a lateral or side motion, producing such a result as that of grinding. It is probable that, from observation on the action of the teeth, the "draw cut," so essential to the perfection of tools that really cut, has been suggested.

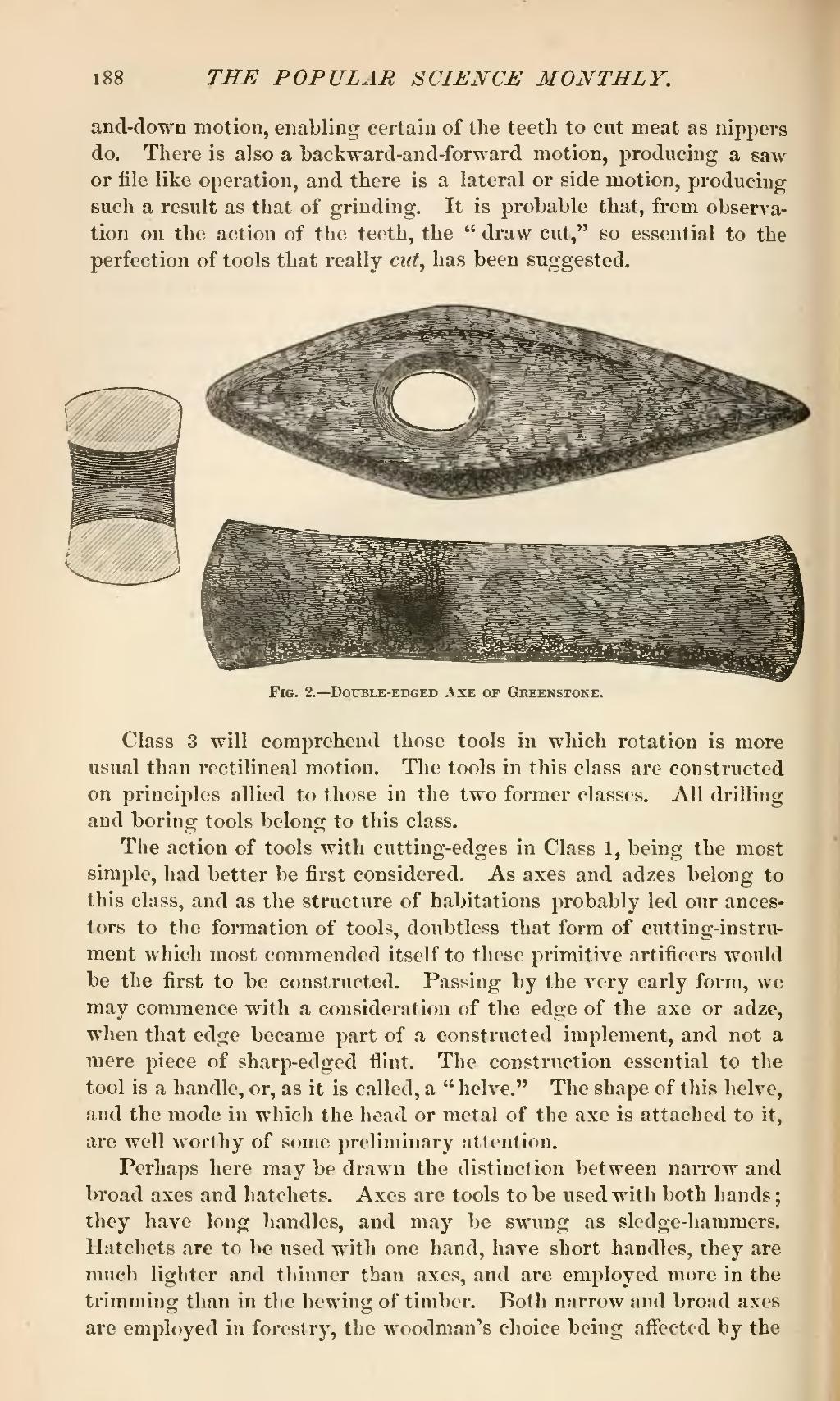

Fig. 2.—Double-edged Axe of Greenstone.

Class 3 will comprehend those tools in which rotation is more usual than rectilineal motion. The tools in this class are constructed on principles allied to those in the two former classes. All drilling and boring tools belong to this class.

The action of tools with cutting-edges in Class 1, being the most simple, had better be first considered. As axes and adzes belong to this class, and as the structure of habitations probably led our ancestors to the formation of tools, doubtless that form of cutting-instrument which most commended itself to these primitive artificers would be the first to be constructed. Passing by the very early form, we may commence with a consideration of the edge of the axe or adze, when that edge became part of a constructed implement, and not a mere piece of sharp-edged flint. The construction essential to the tool is a handle, or, as it is called, a "helve." The shape of this helve, and the mode in which the head or metal of the axe is attached to it, are well worthy of some preliminary attention.

Perhaps here may be drawn the distinction between narrow and broad axes and hatchets. Axes are tools to be used with both hands; they have long handles, and may be swung as sledge-hammers. Hatchets are to be used with one hand, have short handles, they are much lighter and thinner than axes, and are employed more in the trimming than in the hewing of timber. Both narrow and broad axes are employed in forestry, the woodman's choice being affected by the