in an unusual manner, probably for convenience in holding putty, which he often carries "dabbed" on the handle. In some cases, as in the working of copper vessels which have been silver-plated or gilt, the coats of the precious metals are so thin that, although the weight of a hammer-head is required, yet-even the wooden hammer of the plumber, or the still softer leaden hammer of the engineer, is equally unsuitable, and therefore the workers in these metals cover the face of their hammers at times with one or more layers of cloth.

The veneering hammer is compound, one end being formed of metal and the other of wood. The metal end is used as a squeezing-hammer (if such a term may be employed), and the wooden end as a tapping-hammer, to ascertain by the sound produced where the veneering is adhering and where it is not.

Fig.—11 Mason's Hammer-Head.

The stone-mason seems to claim a universal choice. As to material, he has and frequently uses hammers made of wood, of iron (steel-faced), and of an alloy of lead.

In some cases the hammer and the anvil mutually change places, the hammer of wood, the anvil of metal, or the converse. Nor is the

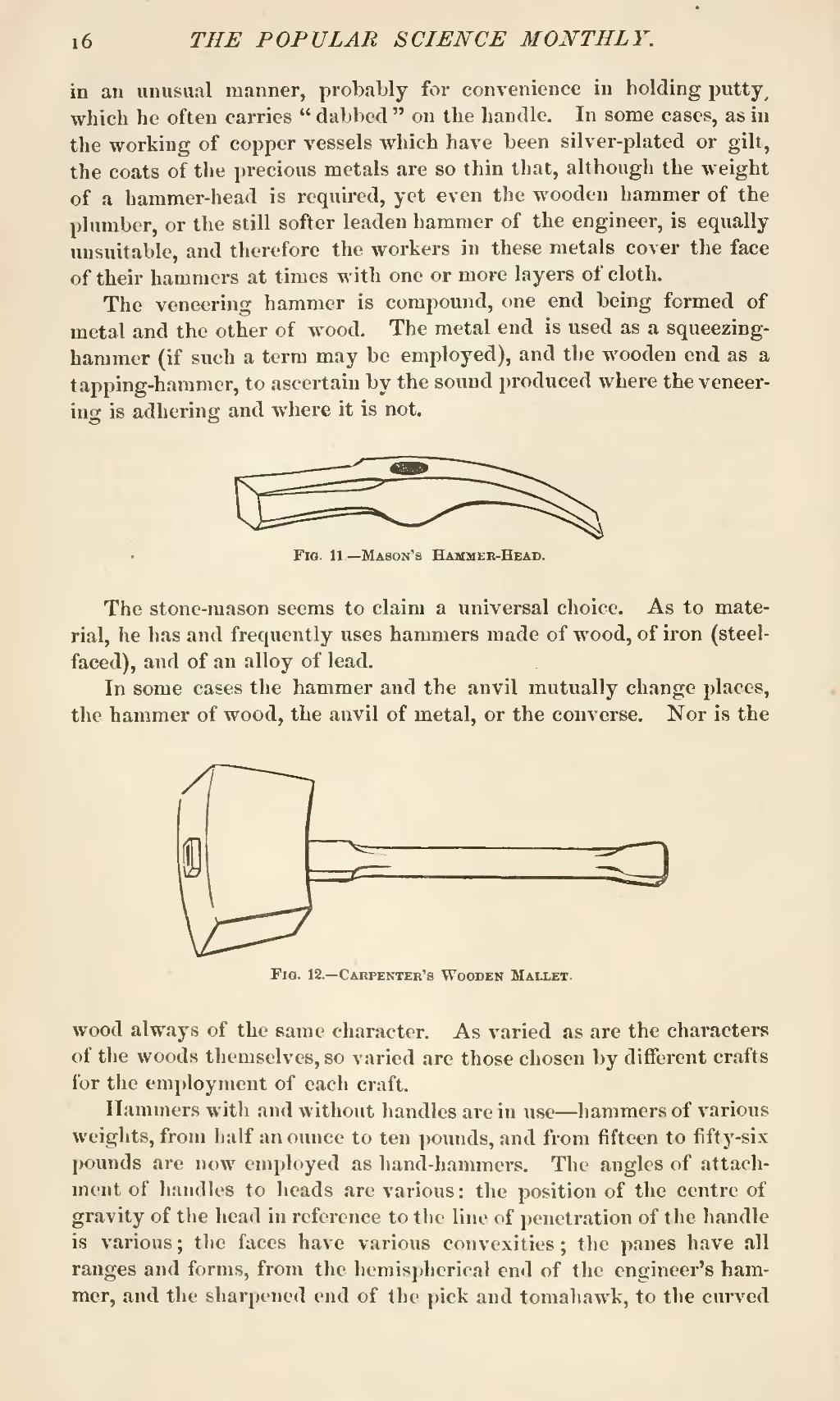

Fig. 12.—Carpenter's Wooden Mallet.

wood always of the same character. As varied as are the characters of the woods themselves, so varied are those chosen by different crafts for the employment of each craft.

Hammers with and without handles are in use—hammers of various weights, from half an ounce to ten pounds, and from fifteen to fifty-six pounds are now employed as hand-hammers. The angles of attachment of handles to heads are various: the position of the centre of gravity of the head in reference to the line of penetration of the handle is various; the faces have various convexities; the panes have all ranges and forms, from the hemispherical end of the engineer's hammer, and the sharpened end of the pick and tomahawk, to the curved