Post-office, a vast increase of business might be done with but little more expense. Accordingly, to gain the increased business they reduced the rates one-half, and succeeded—but not in a pecuniary sense. Prof. Jevons ascribes this disappointing result to the great cost of erecting and maintaining the lines; to their small carrying capacity when compared with that of a railroad-train; and to the number of hands and heads which each telegraphic message has to pass through before reaching its destination, and which must all be paid. But the progress of the last five years, made principally in this country, has demonstrated that these difficulties are not insuperable.

In order of time, the first important step toward this end was the Duplex Telegraph of Mr. Joseph Stearns, of Boston, Massachusetts. Its object is to allow of two operators using the same wire to send messages in opposite directions simultaneously. To persons having only a general acquaintance with the ordinary working of the telegraph, this at first seemed impossible; and, when it was accomplished, it was held by many—some scientific men among the number—to furnish an indubitable proof of the theory that the electric waves, or currents, or whatever they might be held to be, necessarily passed each other in contrary directions over the wire. That they do not will be evident from the subjoined explanation.

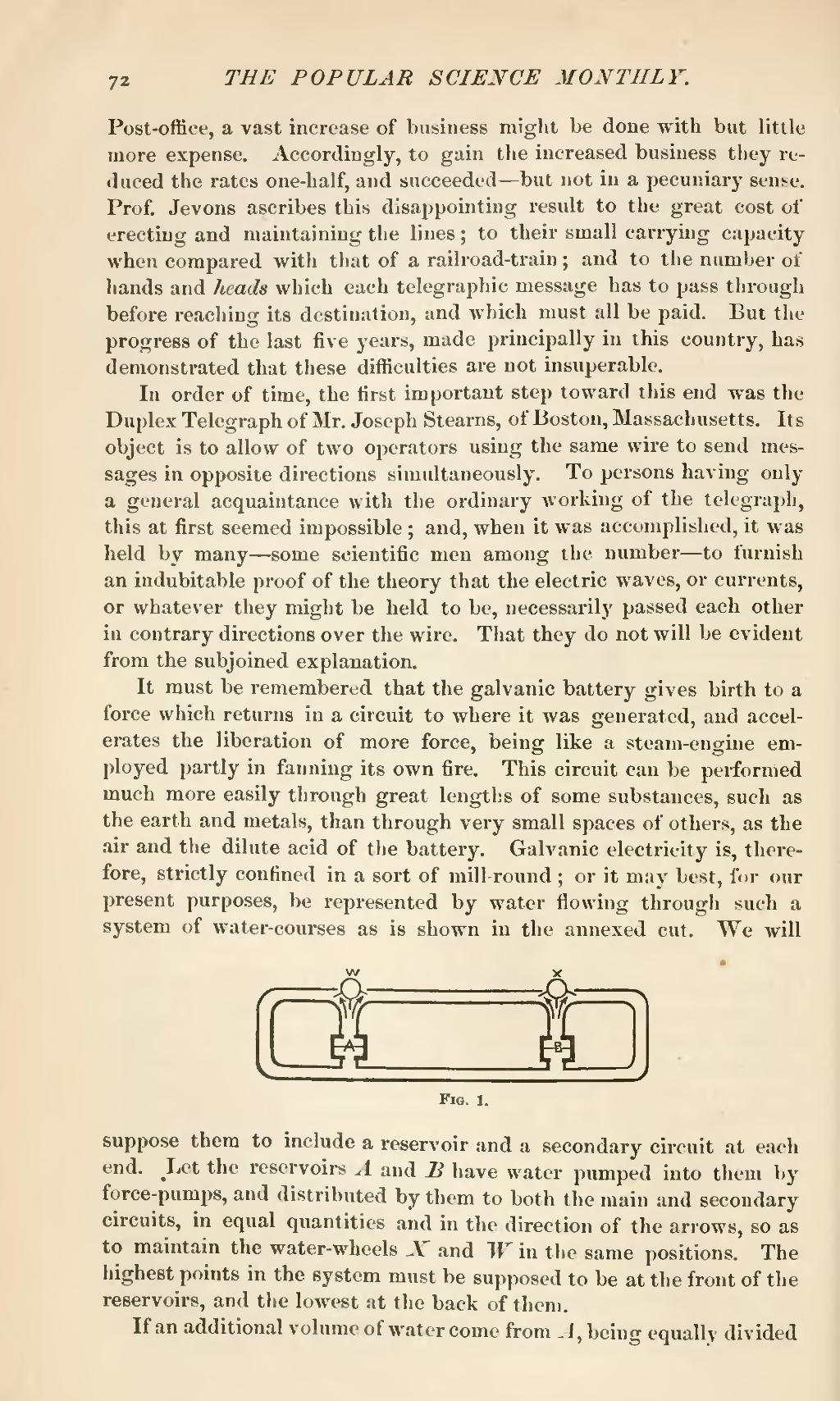

It must be remembered that the galvanic battery gives birth to a force which returns in a circuit to where it was generated, and accelerates the liberation of more force, being like a steam engine employed partly in fanning its own fire. This circuit can be performed much more easily through great lengths of some substances, such as the earth and metals, than through very small spaces of others, as the air and the dilute acid of the battery. Galvanic electricity is, therefore, strictly confined in a sort of mill-round; or it may best, for our present purposes, be represented by water flowing through such a system of water-courses as is shown in the annexed cut. We will

Fig. 1.

suppose them to include a reservoir and a secondary circuit at each end. Let the reservoirs A and B have water pumped into them by force-pumps, and distributed by them to both the main and secondary circuits, in equal quantities and in the direction of the arrows, so as to maintain the water-wheels X and W in the same positions. The highest points in the system must be supposed to be at the front of the reservoirs, and the lowest at the back of them.

If an additional volume of water come from A, being equally divided