2.

In May 1834 I constructed the first magnetic apparatus with a primitive continuous circular motion. It is true that, like M. dal Negro, (with whose labours I regret that I am not better acquainted,) I had several years ago conceived the idea of applying this power to mechanics: but I could not at first divest myself of the idea of making this application by means of an advancing and receding motion, produced by the attractive and repulsive power of magnetic bars,—a motion which, by known means, might have been changed into a continuous circular one. It seemed to me that an apparatus of this kind would have only the merit of an amusing toy, which might find a place in the cabinets of men of science, but would be entirely inapplicable on a large scale with any advantage.

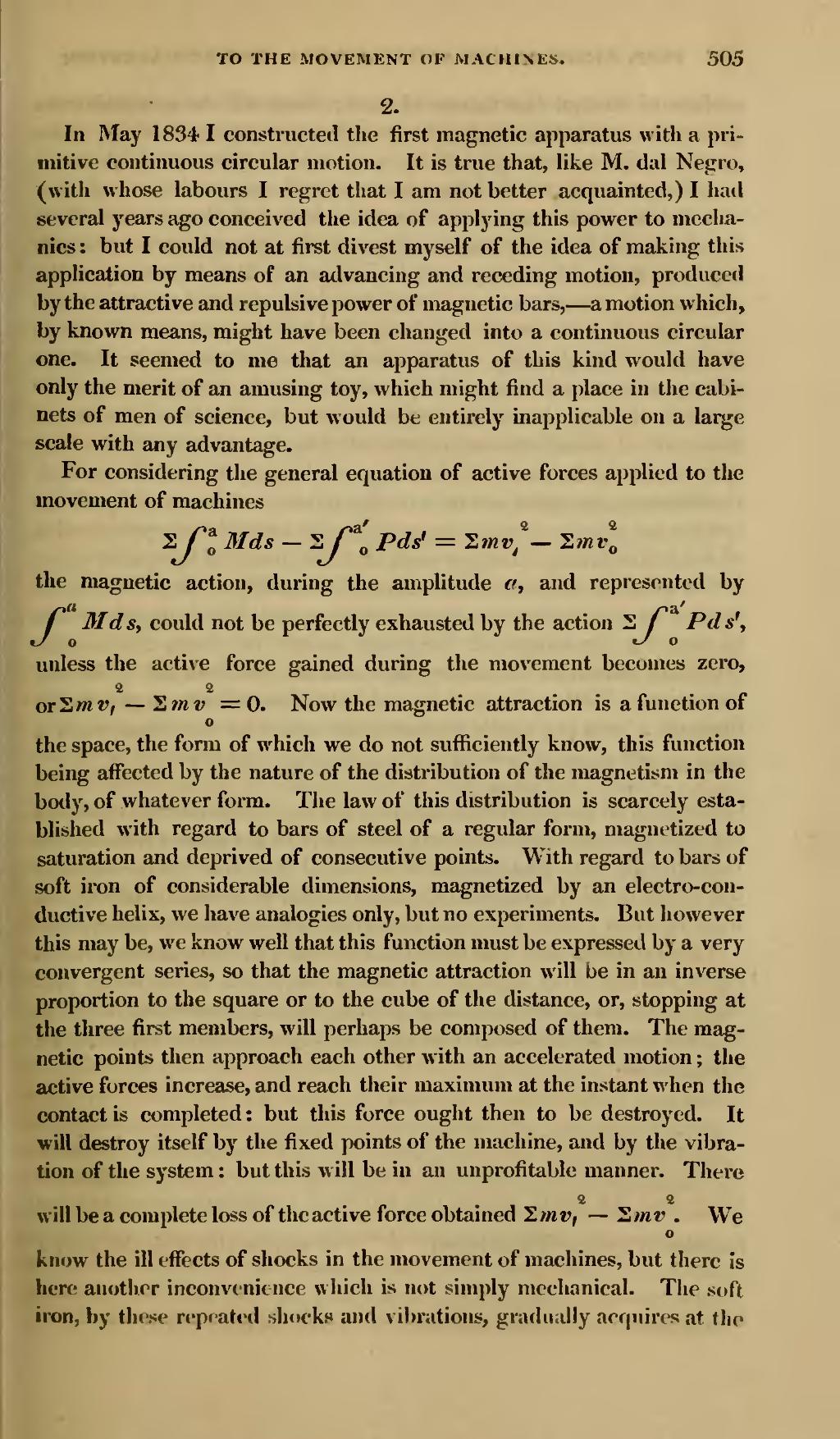

For considering the general equation of active forces applied to the movement of machines

the magnetic action, during the amplitude , and represented by , could not be perfectly exhausted by the action , unless the active force gained during the movement becomes zero, or . Now the magnetic attraction is a function of the space, the form of which we do not sufficiently know, this function being affected by the nature of the distribution of the magnetism in the body, of whatever form. The law of this distribution is scarcely established with regard to bars of steel of a regular form, magnetized to saturation and deprived of consecutive points. With regard to bars of soft iron of considerable dimensions, magnetized by an electro-conductive helix, we have analogies only, but no experiments. But however this may be, we know well that this function must be expressed by a very convergent series, so that the magnetic attraction will be in an inverse proportion to the square or to the cube of the distance, or, stopping at the three first members, will perhaps be composed of them. The magnetic points then approach each other with an accelerated motion; the active forces increase, and reach their maximum at the instant when the contact is completed: but this force ought then to be destroyed. It will destroy itself by the fixed points of the machine, and by the vibration of the system: but this will be in an unprofitable manner. There will be a complete loss of the active force obtained . We know the ill effects of shocks in the movement of machines, but there is here another inconvenience which is not simply mechanical. The soft iron, by these repeated shocks and vibrations, gradually acquires at the