past midnight. Pamela's alibi becomes that of Lady de Chavasse, and is quite conclusive. Besides, that elegant lady was not one to do that sort of work for herself."

"What do you mean?" I asked

"Do you mean to say you never thought of the real solution of this mystery?" he retorted sarcastically.

"I confess———" I began a little irritably.

"Confess that I have not yet taught you to think logically, and to look at the beginning of things."

"What do you call the beginning of this case, then?"

"Can't you picture him, hearing the two women's talk in the next room?"

"Why! the compromising letters, of course."

"But," I argued.

"Wait a minute!" he shrieked excitedly, whilst with frantic haste he began fidgeting, fidgeting again at that eternal bit of string. "These did exist, otherwise why did Lady de Chavasse parley with Pamela Pebmarsh? Why did she not order her out of the house then and there if she had nothing to fear from her?"

"I admit that," I said.

"Very well; then, as she was too fine, too delicate, to commit the villainous murder of which she afterwards accused poor Miss Pamela, who was there sufficiently interested in those letters to try and gain possession of them for her?"

"Who, indeed?" I queried, still puzzled, still not understanding.

"Aye! who but her husband," shrieked the funny creature, as with a sharp snap he broke his beloved string in two.

"Her husband!" I gasped.

"Why not? He had plenty of time, plenty of pluck. In a flat it is easy enough to overhear conversations that take place in the next room—he was in the house at the time, remember, for Lady de Chavasse said herself that he went out afterwards. No doubt he overheard everything—the compromising letters, and Pamela's attempt at levying blackmail. What the effect of such a discovery must have been upon the proud man I leave you to imagine—his wife's social position ruined, a stain upon his ancient name, his relations pointing the finger of scorn at his folly.

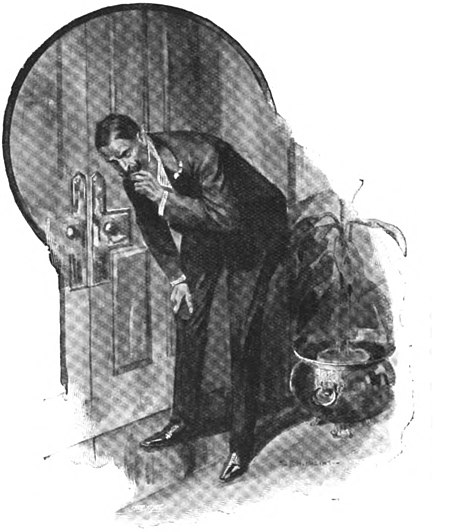

"Can't you picture him, hearing the two women's talk in the next room, and then resolving at all costs to possess himself of those compromising letters? He had just time to catch the 10 train to Boreham Wood.

"Mind you, I don't suppose that he went down there with any evil intent. Most likely he only meant to buy those letters from Miss Pebmarsh. What happened, however, nobody can say but the murderer himself.

"Who knows? But the deed done, imagine the horror of a refined, aristocratic man face to face with such a crime as that.

"Was it this terror, or merely rage at the girl who had been the original cause of all this, that prompted him to commit the final villainy of writing out a false accusation and placing it under the dead woman's hand? Who can tell?

"Then, the deed done, and the mise-en-scène complete, he is able to catch the last train—11.23—back to town. A man travelling alone would pass practically unperceived.

"Pamela's innocence was proved, and the murder of Miss Pebmarsh has remained a mystery, but if you will reflect on my conclusions you will admit that no one else—no one else—could have committed that murder, for no one else had a greater interest in the destruction of those letters."