Maestrissimo!

HE has been in America now for nearly twenty years. He is still the best type of an Italian gentleman. For Giulio Gatti-Casazza that is quite enough.

In every opera house in the world, from Palermo to Colon, there are more than a hundred maestros. Even the piccolo player goes by that name. Any doorkeeper will slip you gratis into the house if you salaam him with the magic title. But they never permit you to forget that there is only one maestrissimo, one impresario, one chief unimpeachable, incomparable. Behold him here in Signor Gatti-Casazza of the Metropolitan Opera Company.

According to the biographies he is not yet sixty. He looks older than that, though. He has already about him the frosty dignity, the calm chagrin of a septuagenarian.

Provided you can speak Italian, or understand his French, he can be voluble enough on one or two topics. He has as little respect for French operas as he has for American criticisms. He must produce one or two of the former, every season or so. He must read the latter now and then—or, rather, have them read to him by a tactful translator. Catch him in his own big, brocaded sanctum, or better still, in the giddy, fumy coop of a publicity office, just off the stars’ stage entrance, and quote him just two words of Deems Taylor’s on the subject of “William Tell.” Up fly his arms, hands writhing on his wrists, fingers spread like the boulevards of Paris from an airplane. He hisses, he sprays the air around him. There is no checking him for the next hour.

That is a rare occurrence, though. Six and three-quarter days out of every week he preserves the fiction of a courteous, imperturbable, quite inscrutable Jove. Silence is a great aid to him, there. It is the apron he puts on while kneading, over and over, the personnel and property of his company. It preserves his air, not only of efficiency, but of mystery.

He will sit for hours among vivid talkers—even at some dinner in his honor—without spilling more than an occasional monosyllable down upon his embonpoint. He takes a splendid, mute pleasure in sinking upon the small of his back, for his big shoulders droop and seem tired nowadays. In their eloquent way they sum up his seventeen years in a land of plenty, a land of strangers. So, at table, at his desk, in the audience room … the small of his back … and the silent, exquisite comfort of fondling his nose.

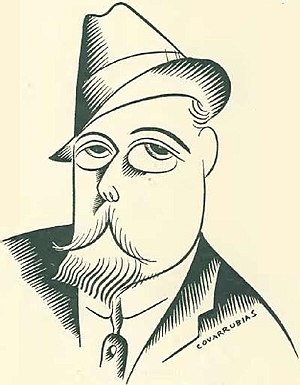

Giulio Gatti-Casassa

It is a fine, memorable feature, this Gatti-Casazza nose, It is the sharpest, most assertive part of his wise, sensitive, melancholy face. The bone of it presses hard upon the skin and leaves it bloodless. There is extraordinary aquilinity there, a twist of the cartilage which confers owl-like shrewdness on the big forehead, cheeks and beard surrounding it. The beard is of that forked variety known as Swiss, much favored by modern Roman senators. It adds to the illusion of an owl's disk of radiating feathers.

He is tremendously well educated, scientifically and artistically. Centuries of courtly breeding are behind his culture, His family were distinguished Ferrarese and Romans, musicians, financiers and honorary senators. He himself was taught at the haughtiest of schools and universities of Italy, graduating a naval engineer. Then suddenly, when he was still in his twenties, circumstances bundled him into the directorship of a small municipal opera company. Five years later his conspicuous ability put him in charge of La Scala, Milan, and he made of it the greatest opera house in the world. He came to the Metropolitan in 1908. He has stayed there longer than any other impresario. The rumor of his resignation never arises but that another two or three years are added to his contract, surrounded by the flourishes of high praise from Mr. Otto H. Kahn and other directors of the company.

They are a bit bored by the Metropolitan repertory, the most of them; and you can persuade them to say so in a confidential moment. They believe in Signor Gatti-Casazza, though, because of his patent honesty, his stability, his fair economy, his tact in melting great reputations down to the convenience of one big, elephantine, somewhat commonplace, undeniably successful company. He gives the public what it likes, and the public—through a board of Metropolitan directors—compensates him generously.

For the public′s sake he has persuaded himself that opera is as much a social as a musical institution. If the public prefers “Tosca” for the benefit of the Save-a-Pet Home to “Don Giovanni” for the good of its own soul … it is the American public after all. And if the American public doesn't like novelties—ecco! Revive them some Verdi!

He loves to mount operas with ships in them: “Tristan” and “L’Africana,” for example. It makes you wonder, does he hanker for the old naval engineering days? He might have been building navies instead of backdrops and repertories, He might have been commanding seas instead of ballets. Perhaps this is his secret sorrow.

For he has one, that is sure. Perhaps, again, it is simply a disinclination to discover America, a reluctance which has built up a defensive disdain. He has found it as unnecessary to study