Problem 79

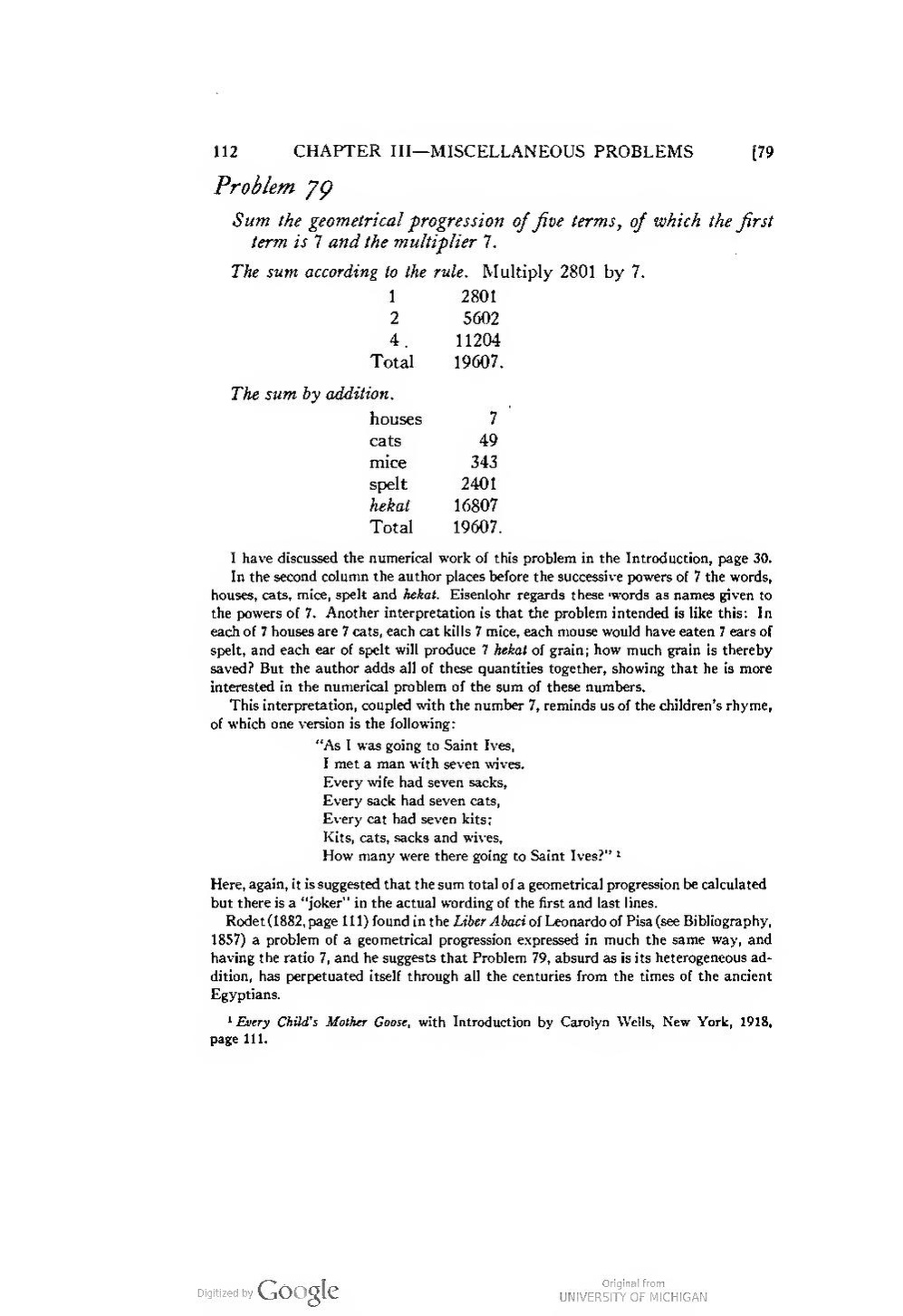

Sum the geometrical progression of five terms, of which the first term is 7 and the multiplier 7.

The sum according to the rule. Multiply 2801 by 7.

| 2801 | ||

| 2 | 5602 | |

| 4 | 11204 | |

| Total | 19607. |

The sum by addition.

| houses | 7 | |

| cats | 49 | |

| mice | 343 | |

| spelt | 2401 | |

| hekat | 16807 | |

| Total | 19607. |

I have discussed the numerical work of this problem in the Introduction, page 30. In the second column the author places before the successive powers of 7 the words, houses, cats, mice, spelt and hekat. Eisenlohr regards these words as names given to the powers of 7. Another interpretation is that the problem intended is like this: In each of 7 houses are 7 cats, each cat kills 7 mice, each mouse would have eaten 7 ears of spelt, and each ear of spelt will produce 7 hekat of grain; how much grain is thereby saved? But the author adds all of these quantities together, showing that he is more interested in the numerical problem of the sum of these numbers.

This interpretation, coupled with the number 7, reminds us of the children's rhyme, of which one version is the following:

"As I was going to Saint Ives,

I met a man with seven wives.

Every wife had seven sacks,

Every sack had seven cats,

Every cat had seven kits;

Kits, cats, sacks and wives,

How many were there going to Saint Ives?"[1]

Here, again, it is suggested that the sum total of a geometrical progression be calculated but there is a "joker" in the actual wording of the first and last lines.

Rodet (1882, page 111) found in the Liber Abaci of Leonardo of Pisa (see Bibliography, 1857) a problem of a geometrical progression expressed in much the same way, and having the ratio 7, and he suggests that Problem 79, absurd as is its heterogeneous addition, has perpetuated itself through all the centuries from the times of the ancient Egyptians.

- ↑ Every Child's Mother Goose, with Introduction by Carolyn Wells, New York, 1918, page 111.