This page has been validated.

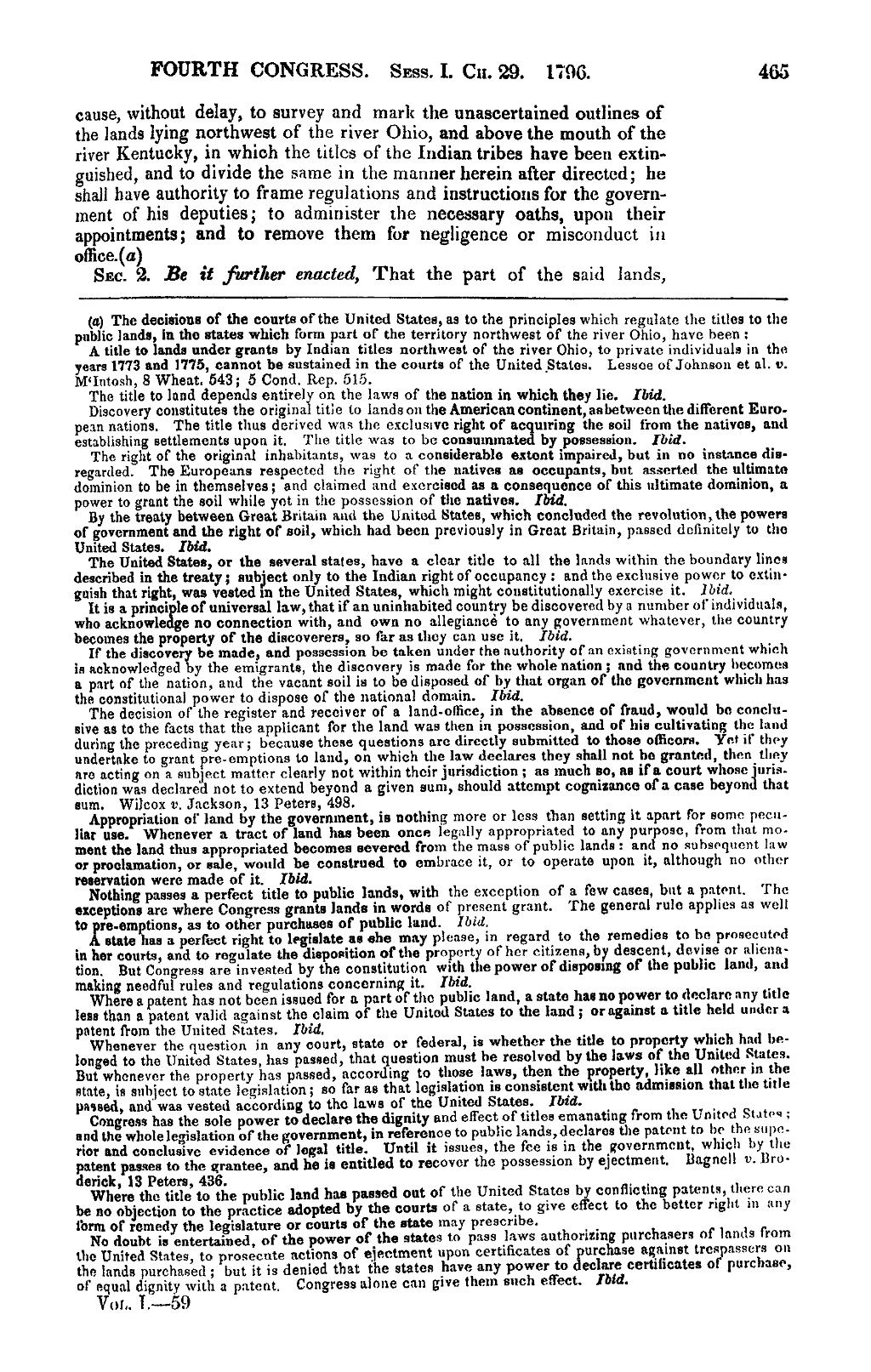

FOURTH CONGRESS.Sess. I. Ch. 29.1796.

cause, without delay, to survey and mark the unascertained outlines of the lands lying northwest of the river Ohio, and above the mouth of the river Kentucky, in which the titles of the Indian tribes have been extinguished, and to divide the same in the manner herein after directed; he shall have authority to frame regulations and instructions for the government of his deputies; to administer the necessary oaths, upon their appointments; and to remove them for negligence or misconduct in office.[1]

Sec. 2. Be it further enacted, That the part of the said lands,- ↑ The decisions of the courts of the United States, as to the principles which regulate the titles to the public lands, in the states which form part of the territory northwest of the river Ohio, have been:A title to lands under grants by Indian titles northwest of the river Ohio, to private individuals in the years 1773 and 1775, cannot be sustained in the courts of the United States. Lessee of Johnson et al. v. M’Intosh, 8 Wheat. 543; 5 Cond. Rep. 515.The title to land depends entirely on the laws of the nation in which they lie. Ibid.Discovery constitutes the original title to lands on the American continent, as between the different European nations. The title thus derived was the exclusive right of acquiring the soil from the natives, and establishing settlements upon it. The title was to be consummated by possession. Ibid.The right of the original inhabitants, was to a considerable extent impaired, but in no instance disregarded. The Europeans respected the right of the natives as occupants, but asserted the ultimate dominion to be in themselves; and claimed and exercised as a consequence of this ultimate dominion, a power to grant the soil while yet in the possession of the natives. Ibid.By the treaty between Great Britain and the United States, which concluded the revolution, the powers of government and the right of soil, which had been previously in Great Britain, passed definitely to the United States. Ibid.The United States, or the several states, have a clear title to all the lands within the boundary lines described in the treaty; subject only to the Indian right of occupancy: and the exclusive power to extinguish that right, was vested in the United States, which might constitutionally exercise it. Ibid.It is a principle of universal law, that if an uninhabited country be discovered by a number of individuals, who acknowledge no connection with, and own no allegiance to any government whatever, the country becomes the property of the discoverers, so far as they can use it. Ibid.If the discovery be made, and possession be taken under the authority of an existing government which is acknowledged by the emigrants, the discovery is made for the whole nation; and the country becomes a part of the nation, and the vacant soil is to be disposed of by that organ of the government which has the constitutional power to dispose of the national domain. Ibid.The decision of the register and receiver of a land-office, in the absence of fraud, would be conclusive as to the facts that the applicant for the land was then in possession, and of his cultivating the land during the preceding year; because these questions are directly submitted to those officers. Yet if they undertake to grant pre-emptions to land, on which the law declares they shall not be granted, then they are acting on a subject matter clearly not within their jurisdiction; as much so, as if a court whose jurisdiction was declared not to extend beyond a given sum, should attempt cognizance of a case beyond that sum. Wilcox v. Jackson, 13 Peters, 498.Appropriation of land by the government, is nothing more or less than setting it apart for some peculiar use. Whenever a tract of land has been once legally appropriated to any purpose, from that moment the land thus appropriated becomes severed from the mass of public lands: and no subsequent law or proclamation, or sale, would be construed to embrace it, or to operate upon it, although no other reservation were made of it. Ibid.Nothing passes a perfect title to public lands, with the exception of a few cases, but a patent. The exceptions are where Congress grants lands in words of present grant. The general rule applies as well to pre-emptions, as to other purchases of public land. Ibid.A state has a perfect right to legislate as she may please, in regard to the remedies to be prosecuted in her courts, and to regulate the disposition of the property of her citizens, by descent, devise or alienation. But Congress are invested by the constitution with the power of disposing of the public land, and making needful rules and regulations concerning it. Ibid.Where a patent has not been issued for a part of the public land, a state has no power to declare any title less than a patent valid against the claim of the United States to the land; or against a title held under a patent from the United States. Ibid.Whenever the question in any court, state or federal, is whether the title to property which had belonged to the United States, has passed, that question must be resolved by the laws of the United States. But whenever the property has passed, according to those laws, then the property, like all other in the state, is subject to state legislation; so far as that legislation is consistent with the admission that the title passed, and was vested according to the laws of the United States. Ibid.Congress has the sole power to declare the dignity and effect of titles emanating from the United States; and the whole legislation of the government, in reference to public lands, declares the patent to be the superior and conclusive evidence of legal title. Until it issues, the fee is in the government, which by the patent passes to the grantee, and he is entitled to recover the possession by ejectment. Bagnell v. Broderick, 13 Peters, 436.Where the title to the public land has passed out of the United States by conflicting patents, there can be no objection to the practice adopted by the courts of a state, to give effect to the better right in any form of remedy the legislature or courts of the state may prescribe.No doubt is entertained, of the power of the states to pass laws authorizing purchasers of lands from the United States, to prosecute actions of ejectment upon certificates of purchase against trespassers on the lands purchased; but it is denied that the states have any power to declare certificates of purchase, of equal dignity with a patent. Congress alone can give them such effect. Ibid.