Panama, past and present/Chapter 13

CHAPTER XIII

HOW WE ARE BUILDING THE CANAL

TO give a complete history of the building of the Canal, from the arrival of the first American steam-shovel to the final merging of the construction into the operating force, would take a library of little books like this. The best I can hope for is to give the reader some slight idea of what we might have seen, had we crossed the Isthmus together, in the days of the canal-builders. Let us imagine that we are taking such a trip.

As we steam into Limon Bay, after a two-thousand-mile voyage from New York, you will notice the long breakwater that is being built out from Toro Point, to make this a safe harbor, and also to keep storms and tides from washing the mud back into the four miles of canal that run under the sea to deep water. Down this channel comes something that looks like a very fat ocean steamer, and when it reaches the end it rises several feet in the water, turns round, and waddles back again. This is the sea-going dredge Caribbean, busy sucking up the bottom into its insides, and carrying it away. This craft is painted white, with a buff superstructure, as our warships used to be, and when it first came to the Isthmus, the quarantine officer put on his best suit of white duck, and went out to take breakfast on board the "battleship." Many other smaller dredges are dipping up rock into barges or pumping mud through long pipes to the land, all the way to the shore, and up the four miles of sea-level canal to where the Gatun Locks loom in the distance. All this you can see as we cross the bay to the ugly town of Colon, and its pretty suburb of Cristobal, which last is in the American Canal Zone, and the place where the steamers dock.

Now that you have seen what these dredges can do, you will ask me why we do not dig the rest of the Canal that way, instead of bothering with locks and dams, and I can give you the answer in five words: because of the Chagres River. This troublesome stream, as you can see by the map on page 4, comes down from the San Blas hills, strikes the line of the Canal at a place called "Bas Obispo," and zigzags across it to Gatun. And though we can dredge a channel up to Gatun, or scoop out the Gaillard Cut, which is an artificial cañon nine miles long through the hills between Bas Obispo and Pedro Miguel, on the Pacific side of the divide, we could not dig below the bed of the Chagres without having a lot of waterfalls pouring into the Canal, washing down the banks and silting up the channel. And as the Chagres is a sizable river that has been known to rise more than twenty-five feet in a night—for the rainfall at Panama is very severe—you can see that it is no easy problem to control it. But we have solved that problem by means of the Gatun Dam.

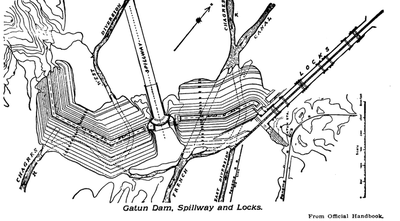

At Gatun, the valley of the Chagres is only about a mile and a quarter wide, and by closing the gap between the hills on either side with an artificial hill—for that is what the Gatun Dam really is—we accomplish two things: first, by backing up the river behind the dam, we form a deep lake that will float our ships up against the side of the hills at Bas Obispo, and make so much less digging in the Gaillard Cut; and, second, a flood that would cause a rise of twenty-five feet in the river would not cause one of a quarter of an inch in the big lake, that will have an area of nearly two hundred square miles.

In building the dam that is to hold back all this water, two trestles were driven across the valley, and from them were dumped many train-loads of hard rock from the Gaillard Cut, to form what the engineers call the "toes" of the dam. To fill the space between them, dredges pump in muddy water that filters away between the cracks of the toes, leaving the sediment it carried to settle and form a solid core of hard-packed clay, over a quarter of a mile thick. When the dam is finished, the side toward the lake will be thoroughly riprapped with stone to prevent washing by the waves, and so gentle will be the slope that you could ride over it on a bicycle without rising on the pedals.

To keep the water from running over the top of the dam, the engineers have cut a new channel for the Chagres through a natural hill of rock that stands in the center of the valley, and this, lined with concrete and fitted with regulating works, is what they call the "spillway." When the dam is finished, the spillway will be

FINISHED SECTION OF CULEBRA CUT AT BAS OBISPO.

The water in the drainage ditch is four feet below the level of the completed canal.

closed, and then the tremendously heavy rainfall—from ten to fifteen feet a year—will fill the lake in less than a twelvemonth. All the surplus water will run off through the spillway, and as it runs it will pass through turbines and turn dynamos to generate electricity for operating the machinery of the Gatun Locks that will lift ships over the dam.

These locks are in pairs, like the two tracks of a railroad, so that ships can go up and down at the same time; three pairs, like a double stairway, of great concrete tanks each big enough for a ship a thousand feet long, a hundred and ten feet wide, and forty-two feet deep to float in it like a toy boat in a bath-tub. You can get some idea of their size when you remember that the Titanic was only eight hundred and fifty-two feet long. Or, to put it another way: every one of these six locks (and there are six more on the Pacific side) contains more concrete than there is stone in the biggest pyramid in Egypt.[2] The American people have been able to do more in half a dozen years than the Pharaohs in a century, for our machinery has given us the power of many myriads of slaves.

And wonderful machinery it is at Gatun, both human and mechanical. It is not easy for a visitor, standing on one of the lock walls—which, as you can see from the diagram, is as high as a six-story house—and looking down into the swarming, clanging lock-pits, to see any system, but if he look closely, he can trace its main

GATUN LOCKS

Steel frame for casting a section of the square centre wall.

outlines. Up the straight four-mile channel from Limon Bay come many barges, towed either by sturdy sea-going tugs or an outlandish-looking, stern-wheel steamer called the Exotic. Some of these barges are laden with Portland cement from the United States, others with sand from the beaches of Nombre de Dios, or crushed stone

SECTIONAL VIEW OF A LOCK, AS HIGH AS A SIX-STORY BUILDING.

The tube through which the water Is admitted is large enough to hold a locomotive.

from the quarries of Porto Bello. (For both of these old Spanish ports are now alive again, helping in the building of the Canal, and every now and then one of our dredges strikes the hull of a sunken galleon, or brings up cannon-balls or pieces-of-eight.)[3] The cargoes of all these barges are snatched up by giant unloader-cranes and put into storehouses, out of which, like chicks from a brooder, run intelligent little electric cars that need no motormen, but climb of themselves up into the top story of the dusty mixing-house. Here, eight huge rotary mixers churn the three elements, cement, sand, and stone, into concrete, and drop it wetly into great skips or buckets, two of which sit on each car of a somewhat larger-sized system of electric trains, whose tracks run along one side of the lock-pits. Presently those skips rise in the air and go sailing across the lock-pit in the grip of a carrier traveling on a steel cable stretched between two of the tall skeleton towers that stand on either side of the lock-site. When the skip is squarely above the one of the high steel molds it is to help fill, it is tilted up, and there is so much more concrete in place.

When the last cubic yard has been set, the gates hung, and the water turned in, a ship coming from the Atlantic will stop in the forebay or vestibule of the lowest right-hand locks, and make fast to electric towing-locomotives running along the top of the lock-walls. No vessel will be allowed to enter a lock under her own power, for fear of her ramming a gate and letting the water out, as a steamer did a few years ago in the "Soo" Locks, between Lake Huron and Lake Superior. Every possible precaution has been taken to prevent such an accident at Gatun. Any ship that tried to steam into one of the locks there, for any reason whatsoever, would first have to carry away a heavy steel chain, that will always be raised from the bottom as a vessel approaches, and never lowered until she has come to a full stop. Then the

PEDRO MIGUEL LOCKS

Arches for carrying the touring locomotive tracks from level to level.

runaway ship would crash, not into the gates that hold back the water, but a pair of massive "Guard gates," placed below the others for this very purpose.

"The lock gates will be steel structures seven feet thick, sixty-five feet long, and from forty-seven to eighty-two high. They will weigh from three hundred

A BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF ONE OF THE NINETY-TWO PANAMA

"BULL-WHEELS."

This wheel was invented by Mr. Edward Schildhauer of the Isthmian Canal Commission. The wheel revolves horizontally and thrusts out from the side of each lock-wall a long steel arm that opens and closes one of the huge lock-gates. These gates are of the "miter" pattern, so called because, when closed, they make a blunt wedge pointing up-stream, like the slope of a bishop's miter. Observe the curved and hollowed recesses in the lock-walls into which the open gates fold back, like the blades of a knife into the handle. There are, of course, two "bull-wheels"; one for each of the gates.

to six hundred tons each. Ninety-two leaves will be required for the entire Canal, the total weighing fifty-seven thousand tons. Intermediate gates will be used in the locks, in order to save water and time, if desired, in locking small vessels through, the gates being so placed as to divide the locks into chambers six hundred and four hundred feet long, respectively. Ninety-five per cent, of the vessels navigating the high seas are less than six hundred feet long."[4]

You will notice that each leaf of a pair of these gates is sixty-five feet long, instead of fifty-five or half the width of a lock. When they are closed, they form a blunt wedge pointing upstream, and the pressure of the water only keeps them tighter shut. Finally, if all the gates were swept away, there would still remain the

From Official Handbook.

CROSS SECTION OF LOCK CHAMBER AND WALLS OF LOCKS.

A—Passageway for operators.

B—Gallery for electric wires.

C—Drainage gallery.

D—Culvert in center wall.

E—Culverts under the lock floor.

F—Wells opening from lateral culverts into lock chamber.

G—Culvert in sidewalls.

H—Lateral culverts.

"emergency dam" at the head of each flight of locks, ready to be swung round and dropped into position like a portcullis.

Once a ship is inside, the lower gates will be closed behind her by machinery hidden in the square center-pier, valves will be opened, and water from the lake will rush down the conduits in the walls and flow quietly in from below, until it has reached the level of the lock above. Then the upper gates will open, and the electric locomotives,—there will be four of them to handle every big ship, one at each corner,—will go clicking and scrambling up the cog-tracks carried on broad, graceful arches from level to level, and then pull the ship through after them. In like manner will she pass through the two upper locks, and out on the wide waters of Gatun Lake, eighty-five feet above the level of the sea.

The average time of filling and emptying a lock will be about fifteen minutes, without opening the valves so suddenly as to create disturbing currents in the locks or approaches. The time required to pass a vessel through all the locks is estimated at three hours; one hour and a half in the three locks at Gatun, and about the same time in the three locks on the Pacific side. The time of passage of a vessel through the entire canal (about fifty miles from deep water in one ocean to deep water in the other; forty from beach to beach), is estimated as ranging from ten to twelve hours, according to the size of the ship, and the rate of speed at which it can travel."[5]

The time spent by a ship in the locks at Panama will be more than made up by the much greater ease and speed with which she will be able to navigate the rest of the Canal there, as compared with that at Suez, where steamers must crawl at a snail's pace, or the wash from their propellors will bring down the sandy banks; and two large liners cannot meet and pass without one of them having to stop and tie up to the shore. At no place on the Panama Canal will this be necessary, for even at its narrowest part—the nine miles through the Gaillard Cut—the channel will be three hundred feet wide at the bottom, giving plenty of elbow-room for the largest ships, and lined with concrete where it is not hewn out of solid rock. The under-water and sea-level sections at either entrance will be five hundred feet wide, and through the greater part of the Gatun Lake, a ship will steam at full speed down a magnificent channel one thousand feet broad, with no more danger of washing the banks than if she were in the middle of the lower Amazon.

To help night navigation, there will be long rows of acetylene buoys, so ingeniously made that the difference of a few degrees of heat regularly caused on the Isthmus by the rising and setting of the sun, will serve to turn their light off and on, by expanding and contracting a little copper rod. This device, invented by one of the American canal employees, has been thoroughly tested, and found to work perfectly. Everywhere trim little concrete lighthouses, looking strange enough in the jungle, are being built, or, rather, cast in one piece, on wooded hilltops that will soon be islands.

Already the yellow water is rapidly backing up, as the dam and the spillway gates are being raised. You can mark the spread of the lake by the gray of the dying, drowned-out trees against the green of the living jungle. Only in the channel and the anchorage basin has Gatun Lake been cleared of timber, and the greater part of it will be a mass of stumps and snags. The centuries-old trade-route down the Chagres has been wiped out, and more than a dozen little towns and villages, Ahorca Lagarto, Frijoles, San Pablo, Matachin,[6] have been moved to new sites on higher ground. It was not easy to make the natives believe that these places that had been inhabited for hundreds of years would soon be

RELOCATING THE PANAMA RAILROAD

under forty feet of water. Some thought the Americans were prophesying a second deluge. "Ah, no, Señores," protested one old Spaniard, "the good God destroyed the world that way once, but He will never do so again."

The Panama Railroad, too, has been relocated for its entire length, except for two miles or so out of Panama City, and a little over four miles between Colon and Gatun. Both the former station and the old village at Gatun (which is the place where Morgan's bucaneers and the Forty-niners, and all the other travelers up-river spent the first night) are now buried under the huge mass of the Gatun Dam, The former line of the Panama Railroad through the lake-bed, though double-tracked and modernized only a few years ago, has been completely abandoned. The new, permanent, single-track road swings to the east at Gatun, and runs on high ground round the shore of the lake to a bridge across the Chagres at Gamboa, a little above Bas Obispo. It was originally planned that the railroad should run from here through the Gaillard Cut on a "berm" or shelf, ten feet above the surface of the water, but the many slides caused this to be abandoned, and the line was built through the hills on the eastern side of the Cut. At Miraflores it runs through the only tunnel on the Isthmus. Because of the very heavy cuts and fills, the relocation of the Panama Railroad has cost $9,000,000, or $1,000,000 more than building the original road, although the new line is about a mile shorter. It is very solidly built, with steel bridges, concrete culverts, steel telegraph poles, made of lengths of old French rails bolted together and set up on end, and embankments filled with several million cubic yards of rock from the Cut.

Only a little rock was taken out of the Gaillard Cut by the French, most of their digging being what the engineers call "soft-ground work." But the deeper part of the great nine-mile trench, which they left for the Americans to dig, is almost entirely a "hard-rock job." From Bas Obispo to Pedro Miguel (which every American on the Isthmus calls "Peter Magill") it must be hewn and blasted out of solid stone. Row above row of steam or compressed-air drills are boring deep holes in the terraces beneath them, and gangs of men are kept busy filling these holes with dynamite. As much as twenty-six tons were used in one blast, when an entire hillside was blown to pieces, and twice every day, when the men have left the Cut for lunch or to go home, hundreds of reports go rattling off like a bombardment.

Then they move up the great steam-shovels to dig out the shattered rock with their sharp-toothed steel "dippers" that can pick up five cubic yards or eight tons, at a time. Think how bulky a ton of coal looks in the cellar, and then imagine eight times that much being lifted in the air, swung across a railroad track, and dropped on a flat-car, as easily as a grocer's clerk would scoop up a pound of sugar and pour it into a paper bag. Boulders too large to handle conveniently are broken up with "dobey shots," small charges of dynamite stuck into crevices, and tamped down with adobe clay. So skilful are the steam-shovel men (all Americans), that they will make one of their huge machines pick up a little pebble rolling down the side of the Cut as easily as you could with your hand; and every one of them is racing the others, and trying to beat the last man's record for a day's excavation. The present record was made on March twenty-second, 1910, when four thousand, eight hundred and twenty-three cubic yards of rock, or eight thousand, three hundred and ninety-five tons were excavated in eight hours by one machine. There are one hundred of these steam-shovels on the Isthmus, and more than fifty of them in the Gaillard Cut, and to see them all purring and rooting together, more like a herd of living monsters than a collection of machinery, is one of the most wonderful spectacles in the world.

Sometimes steam-shovels will be caught and buried by a "slide," an avalanche of rock or a river of mud brought down by some weakness in the banks. Wrecking trains and powerful railroad-cranes are always kept ready to go to their rescue. The worst place is across the Cut from the town of Culebra, where forty-seven acres of hillside are crawling down like a glacier. This is the famous Cucaracha Slide, that began to trouble the French as long ago as 1884; and though two million cubic yards of it have been dug away, there is half as much more to come. Altogether, this slide and the twenty others will have brought twenty million cubic yards of extra material to be taken out of the Cut, by the time the Canal is finished. But our engineers have learned how to stop them, by cutting away the weight at the top of each slide, and that, and the pressure of the water in the finished canal, should keep the banks at rest.

To carry away the rock and earth dug out by the steam-shovels, there is an elaborate railroad system of several hundred miles of track, so ingeniously arranged that the loaded trains travel down-grade and only empty cars have to be hauled up hill. Much rock is used on the Gatun Dam, and also on the breakwaters at either end of the Canal, but most of the material excavated from the Cut is disposed of by filling up swamps and valleys. Every dirt-train (they would call it that on the Isthmus even if it carried nothing but lumps of rock as big as grand pianos), travels an average distance of ten miles to the dumps and has the right of way over passenger trains, specials, and even mail trains. Only for the President of the United States has the line ever been cleared.

At the dumping-ground, each dirt-train is run out on a trestle, and unloaded in one of two ways. If it is composed of steel dump-cars, they are tipped up either by hand or compressed air. Most of the trains, however, are of big wooden flat-cars, raised on one side, and connected by steel flaps or "aprons," so that a heavy steel wedge, like a snow-plow, can be drawn from one end of the train to the other by a windlass and cable, thus clearing all the cars in a jiffy. (It is great fun to ride on the big wedge when they are "plowing-off.") When the dirt begins to rise above the edge of the trestle, a locomotive pushes up a machine called the "spreader," that smooths it out into a level embankment, and then another machine, the "track-shifter," picks up the ties and rails bodily, and swings them over to the edge of the new ground. Each of these machines does the work of hundreds of laborers.

Two large machine shops, now at Gorgona and

LIDGERWOOD FLATS BEING UNLOADED

Balboa Dumps, low tide, March, 1908.

A SPREADER

Balboa Dumps, low tide, March, 1908.

From Official Handbook.

MODEL OF PEDRO MIGUEL LOCKS.

Colon, is a shipyard for the tugs and dredges of the Atlantic division, and a huge general storage yard and warehouse for everything from a ten-ton casting for a lock-gate to a box of thumb-tacks for fastening a blueprint of that gate to a drawing-board. Every necessary article is there and in its proper place; and the same is true of the tool-box of the smallest switch-engine. From the top to the bottom there is neither skimping nor waste, but an efficiency like that of a Japanese army in the field.

At Pedro Miguel a ship from the Atlantic will begin the descent on the other side of the divide. The locks on the Pacific side are exactly like those at Gatun, except that instead of having all three pairs together, there is one pair here and two at Miraflores, with a little lake between. From Miraflores, the Canal is being dredged out at sea-level to its Pacific terminus at Balboa, where there will be great docks and warehouses and shipyards on land that has been made by filling in tidal marshes with dirt from the Gaillard Cut. As on the Atlantic side, the Canal will run four miles out under the sea to deep water; and to protect it from storms, a breakwater is being built from the shore to Naos Island, in the Bay of Panama. It is both strange and appropriate that the Panama Canal should have one of its entrances at this island, whose name, the Spanish word for "ship," reminds us that three hundred and fifty years ago it was the port of the city of Old Panama.

- ↑ The greater part of this chapter originally appeared in St. Nicholas, in February, 1912, and no better time could have been chosen for a trip to Panama, either in the flesh or in print. Then the great work, though so near completion that it was possible to see in it the finished design, was still being pushed with undiminished vigor.

- ↑ In the construction of the locks, it is estimated that there will be used approximately four million, two hundred thousand cubic yards of concrete, requiring about the same number of barrels of cement. —Official Handbook of the Panama Canal.

- ↑ See Appendix.

- ↑ Official Handbook.

- ↑ Official Handbook.

- ↑ See Appendix.