Paper and Its Uses/Chapter 13

CHAPTER XIII

DEFECTS AND REMEDIES

Many users of paper look upon that material as being perfectly inert and stable, always of the same quality, and any defect which may arise remediable only by changing the paper. Unfortunately, the printer who uses the paper for letterpress, lithographic, or ruling purposes, finds that paper is not unchangeable, and when work has to be registered upon the paper difficulties often arise, and exchange is not always possible.

The principal difficulties arise from stretching, cockling, creasing, from the surface lifting or picking, from the paper being out of square, from electricity contained in the paper, and from loose particles coming away from the paper in the form of fluff. In addition there are difficulties in getting colour to dry upon certain papers, and in obtaining a solid impression or continuous line from printed or ruled matter.

Reference to the chapter on machine-made papers will serve to give the clue to some of the difficulties, and may suggest the remedy. The pulp, diluted with a large volume of water, consists of innumerable fibres, their length being at least 100 times their diameter, and as is the case of all water-borne bodies travelling in a fast stream, they take up the position in which their length is parallel to the direction of flow. The side shake of the wire alters the position of some of the fibres, and although the alteration is permanent, the majority of fibres remain in a position parallel to the machine direction of the web of paper. Most machine-made papers are dried on the heated cylinders of the paper machine, the diameters of the cylinders being arranged to allow for the consequent contraction of the web, but the fibres are not given the opportunity to adjust themselves as in the case of air-dried papers.

When it is remembered that the papermaking fibres may expand in diameter to the extent of 20 per cent., but only one per cent, in length, it will be seen that the expansion will show itself chiefly in one direction, for the majority of fibres lie side by side. Fortunately the full expansion does not take place. Paper which is properly matured contains water equal to 7 per cent. of its weight. Without this moisture, paper would be brittle, and when this amount is exceeded the paper expands. But paper, as it leaves the calender rolls of the paper machine, contains less than 7 per cent. of water. It is essential that all the water should be dried out of the paper, and the paper is sometimes reeled almost bone-dry, but if the paper is to be super-calendered it is damped before reeling, and left until the paper mellows before calendering. Many papers are cut and packed without much opportunity for maturing, that is, as regards paper, attaining a degree of stability which should be maintained during its manipulation by the printer, and, it is hoped, during the remainder of its career.

All papers have some spaces between the fibres, sometimes partly filled with sizing and loading, but always containing some air space, the amount depending upon the density of the paper. Heavy or dense papers and light or bulky papers are the extremes, 30 to 70 per cent. of air space being examples of the two ends of the scale. The fibres, when expanding, fill some of the air spaces between the fibres, and the expansion can never extend to the 20 per cent, mentioned. Experiments carried out on a litho. paper, 36 lb. royal, showed the maximum expansion from absorption of moisture to be 2½ per cent, but papers do not expand as much as this in working, or register work would be extremely difficult.

Expansion, or stretching as it is usually termed, is caused by absorption of moisture by the finished paper from the atmosphere. The atmosphere always contains some moisture, the amount varying not only from day to day, but from hour to hour. When there is an excess of moisture in the air, as on wet days or when fogs occur, paper will readily absorb the extra moisture, and the absorption will be accompanied by expansion of the sheet, principally across the web, or as it is generally termed, in the cross direction. This propensity of paper really points to the remedy. Paper should be matured and kept in that state, or to put it in other words, it should contain an amount of moisture which is neither increased nor diminished.

Few printers treat the machine-room, letterpress or lithographic, or the ruling-room as places where scientific conditions should be maintained. The use of the wet and dry bulb thermometers in other factories is for a definite purpose, to indicate the state of the atmosphere, and to guide in regulation of temperature and humidity, in order that the manufacturing processes may be carried out under scientific conditions. But the machine-room of the printer, closed for more than half its time, heated perhaps by hot water or steam pipes, sometimes hot, sometimes cold, in wet weather damp, in summer alternately very dry and damp, what wonder if paper expands, contracts, and causes trouble at machine.

The establishments where scientific conditions are observed reap the benefit in increased output, because less work is spoiled by bad register, and less time is spent in getting work to register. Even with the regulation of atmosphere suggested by the use of the dry and wet bulb thermometers or hygrometer, the paper must be matured in the machine-room, that is, the paper must be exposed in order to allow it to absorb moisture if too dry, and to part with moisture if too damp, so that the paper may be as stable as possible while the condition of the machine-room remains constant. It is important that the amount of atmospheric moisture should remain constant, and printers'

engineers will advise on the means of attaining this end.

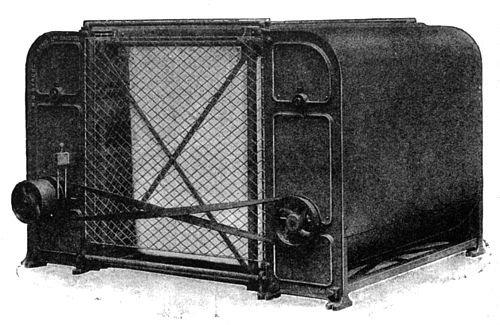

Various methods may be adopted for suspending paper. In some cases the paper is hung over lines, about a quire at a time, exposed to the atmosphere and dust of the machine-room. Hanging frames are supplied by vendors of printers' supplies, in which the paper is clipped by a ball or swinging lever, and about a quire is held in each of the clips, a perpendicular position minimising the danger of dirt. By use of these frames a large quantity of paper can be treated in a comparatively small space. The "Swift" machine is another method of maturing paper. The claim made for the machine is that it matures large quantities of paper in a short time.

The machine consists of two sets of fans, enclosed by iron framing, driven by motor attached or by existing motive power, some four to six reams of paper being suspended in ball clip frames in the space between the two sets of fans. The air of the machine-room is circulated by the fans rapidly through the paper, and maturing takes place in two or three hours.

All paper, after it has been matured, must be stacked, a board and a heavy weight placed on the top of the stack, and the edges protected from getting dirty.

Stretching takes place when paper is subjected to tension or rolling. All cylinder printing machines exert these strains, from the pull of the cylinder and from the printing surface. Difficulty in register will be experienced when a paper stretches much under tension, but it is not so great a trouble as the expansion already referred to. All papers are elastic, and if stretched just within the bounds of the breaking strain of the paper, will show some elongation, permanent or temporary. If the paper returns to its original length there is no permanent stretch, but that is seldom found in practice. The greater expansion of paper is in the cross direction, and the direction of greater stretch of the sheet coincides with that of the larger expansion.

Careful tests of good litho. papers on the Leunig Paper Tester show them to have a mean temporary stretch of 2½ per cent, in the machine direction, with a stretch that is permanent of .68 per cent. The figures for the cross direction of the paper are 4 per cent, and 1½ per cent, respectively. It is the permanent stretch that may cause inconvenience, but the figures quoted must not be taken as an indication of what takes place when printing. A properly adjusted machine does not exert the tension that would be necessary to obtain the percentage of elongation shown above. The fact that lithographers prefer papers cut with the cross direction coincident with the narrower dimension of the sheet is sufficient proof that it is not the machine tension that is dreaded in register work.

Writing and most printing papers, which may or may not be printed in more than one colour, are frequently cut two ways of the webs, that is, a 30 by 40 inch paper, if cut from a web of 70 inches net width, is cut without waste by cutting sheets 30 inches wide from one part and 40-inch sheets from the remainder of the reel. All papers on which register work is to be printed must be cut with the same machine direction. In ordering paper which is not generally used for work in several printings, the printer should be careful to point out the purpose for which it is intended, and ask that the instruction shall, if necessary, be passed on to the papermaker.

Cockling in paper is caused by the paper being drier or damper than the atmosphere, and shows that there is unequal expansion of the sheets, and exposure as detailed above should be tried as a remedy. Cardboards which are cockled may or may not improve upon exposure to the atmosphere. The thicker the cardboard the less likely it is to alter its shape. Usually the fault will have arisen through severe drying under tension, stretching the boards, and drying while unequally stretched. The cockling and wavy edges of boards are frequently found to be permanent faults.

Wavy edges to paper, if at the feed edge, will frequently cause bad creasing, from which damage to the printing surface may result. Creasing from defects of the machine, make-ready, or printing surface must not be visited upon the papermaker. If the paper will not respond to exposure to air, feeding the narrow way of the sheet may overcome the difficulty, or, if the size of the machine permits it, cutting the paper in half and rearranging the forme or other printing surface and putting on an extra feeder.

Art and other coated papers which have the coating fixed to the paper with glue in addition to the liability to wavy edges, may be troublesome by reason of the surface lifting or picking. The latter fault is caused by the coating being insecurely fastened to the body paper, the trouble being temporary or permanent. Storing the paper in a damp place will weaken the adhesive properties of the glue, and the coating will not stand the pull exerted by the printing surface, but will come away in places. The paper may be improved by suspending it to dry off the excess of moisture, but if heated air is used, the temperature should not exceed 90° Fahr. Newly coated papers may cause trouble, owing to the adhesive not being quite hard, and keeping in stock for a fair length of time, a month or two, may result in an entirely satisfactory issue. But if the papers must be used, maturing as already described, with a careful use of heat, will usually remove the trouble altogether. Slight modification of the ink may be necessary, and should be tried before condemning the paper altogether.

It will be found occasionally that the coating is not properly fixed to the paper, owing to insufficient glue, or a soft-sized body paper being used. Damp the thumb and press on the coated paper, lifting it a few seconds after. If a large part or the whole of the coating comes away the coating is at fault. Crumple a piece of the paper, treating it rather severely, and note the amount of coating which has left the paper when flattened out again. A large amount of dust indicates bad coating. Comparative tests should be carried out, a sample known to be satisfactory being tried by the side of the suspected sample.

Fortunately papermakers do not often offend by sending supplies which are out of the square. It does, however, sometimes occur that one edge of the paper is not quite true; folding a sheet in half, with the short edges coincident, will show the extent of deviation from squareness. For ordinary purposes it may not be material if one edge of the paper is one-eighth of an inch out, but if the sheet has to be backed up, care must be taken to feed the longer side into the grippers and to place the side lay, when backing up, at the opposite side exactly at the same point as when first fed. This, of course, is the printer's rule, and in such cases it must be rigidly observed. When paper is fed to the narrow edge, as when two sheets of demy are laid on a double demy machine, the square edge must be the lay edge, or the register of the backing forme will be impossible. For colour work the only safe rule is to trim the two lay edges of all the paper, and, if necessary, to use a larger paper to allow for the trim.

Electricity in paper causes delay in feeding, the sheets sticking together, necessitating an undue use of the cylinder stop. As the paper is reeled at the end of the papermaking machine, electric sparks are frequently to be observed, owing to the electricity generated by friction of the dry paper. A large quantity of the electricity is extracted, but some thin papers with high surface will retain a fair amount, and sheets cling together. Paper which has been exposed for maturing will not give this trouble, and thick papers, even if electrified, do not usually call for special treatment. Elaborate methods have been suggested for discharging the electricity in the paper, but it is a difficult matter, and the most satisfactory plan is to set aside the reams which are troublesome, and in time the electricity will disperse. The use of automatic feeding mechanism is sometimes quoted as a cure for this trouble.

Papers which are loose in texture are usually soft-sized, and thus, having comparatively little size to hold the fibres together, will give off fluff or dust, consisting of small fibres, as soon as the paper is subjected to friction, even of the lightest description. Such paper in its passage through the printing machine gradually deposits its fibrous dust upon the printing surface, the rollers take it from there to the ink distributing surface, and the whole of the inking and printing becomes foul. Such papers are extremely difficult for lithographic printing, and the letterpress printer consumes most of such papers. Soft papers with the mill cut are slightly rough and give off dust, and trimming a clean edge reduces the liability to fluff, but cleaning up at machine (forme, rollers, and ink slab or drum) will be necessary more frequently than is usual. When the machine is stopped for washing up, all parts of the machine carriage which can be reached should be wiped free from dust, as the accumulation will gradually find its way to the rollers when the machine is in motion.

The proper ink for the paper will prove the solution for difficulties in printing on hard papers, and also on very soft papers. It is outside the scope of this work to deal with printing inks, but in regard to coated papers it will be found that all such papers do not behave alike. Some take the ink readily and retain the fullness of colour, while others soak up the varnish and leave the dry colour on the surface. The latter fault is owing to the absorbency of the body paper, and ink must be treated so that the absorbency of the paper is satisfied, and yet the colour and medium remain more on the surface of the paper.

Ruling on papers with hard surface is rendered less difficult by the use of a small amount of gall in the ink. For hand-made papers the ink always requires such manipulation, while for other tub-sized papers a little gum arabic in addition to the gall will render even ruling more easily attainable. In ruling engine-sized papers a small amount of gum arabic and carbonate of soda (ordinary washing soda) will make the colours lie better. While all work can be done on the pen machine, papers with soft surfaces, blottings, duplicating, metallic, and coated papers generally, will give the disc machine opportunity to prove its superiority for this class of work. Cockled papers and very thin papers can be dealt with successfully at the ruling machine by a little manipulation of the pens and feed.

Although rolling, hot or cold, may be effectively used for giving finish to the printed work, the paper is subjected to such great pressure that it is liable to stretch. As pointed out earlier in the chapter, stretching of paper is not equal in both directions of the sheet, and it is advisable, in order to preserve the strength of the paper, to roll in the same direction as the paper was made and rolled in the papermaking machine. Discover the machine direction by the method described on page 86, and feed the paper to the rolling machine in the same way as it left the papermaking machine.

Tub-sized papers may contain or develop a fault which will not occur in engine-sized papers, that of unpleasant smell. A preservative of some kind is frequently added to the sizing solution, but if the gelatine has commenced to decompose the smell will be at least unpleasant. Coated papers contain glue in the coating mixture, and are liable to the same fault. Printers should be careful when buying job lots of tub-sized or coated papers that the cause of the inclusion in the job list is not smell, for a customer cannot be expected to accept a big parcel of printed matter for circulation which is offensive to one of the finer senses, and therefore not likely to prove persuasive to the recipients.

Deterioration of paper has been dealt with already, but there are faults unwittingly developed in some paper which can be avoided by the application of a little forethought. The colouring matters of papers are affected by various things. Some blue colours are discharged (bleached) when acid in any form comes in contact with them, others behave similarly when alkali is encountered. Some buff papers are altered in shade or even in colour by the same agents, and other colours are affected by some but not by all acids. It is not proposed to examine the composition of the colours used by the papermaker, but to point to instances where care is required. When the printer or manufacturing stationer is covering strawboards, boxboards, or millboards with coloured papers, paste or glue may be employed as adhesive, and these are always liable to become acid. To avoid change of colour the use of freshly prepared paste or glue should be adopted. Strawboards frequently contain a certain amount of free alkali, and the colours of papers or cloth mounted upon them may be affected. It may be necessary to change the paper to one which is unaffected by the strawboard, and if this is not feasible, a change of board may be necessary. It is not practicable to neutralise the alkali, as fresh trouble may be caused, and an unsatisfactory result be obtained. Before starting on a big job, tests should be made with the actual materials so that no serious loss by spoilage or stoppage may occur.

All knives, whether circular or straight, must be kept keenly sharpened in order to produce clean edges. Soft cards and papers give more trouble than moderately hard stock when cutting in a guillotine. Some materials should be cut by the rotary cutter when exact measurements are essential, for although it may take longer, for index cards all supplies must be trimmed exactly to the same dimensions, and the very hard index boards are liable to be cut irregularly by the guillotine.

When sheets are ruled or printed, and are afterwards to be bound, the printed or ruled horizontal lines should coincide with the machine direction, or, as it is sometimes expressed, should run with the grain of the paper. The stitching and the binding which secure the leaves will then be fully operative, whereas if the paper is held with the back of the book parallel to the machine direction, the leaves are more liable to break away from the binding.