Paper and Its Uses/Chapter 3

CHAPTER III

MANUFACTURE OF HAND-MADE

AND MOULD-MADE PAPERS

English hand-made paper is still looked upon as the best paper obtainable. Some fourteen firms still make paper by hand, and although the number does not increase, there is no sign of its diminution. The reduction of the rags to fibre was treated in the last chapter. Before leaving the beating engine the colouring matter is added; in the case of a white paper a small amount of blue is necessary to counteract the grey appearance which the natural pulp usually assumes. This is merely equivalent to the blueing which is resorted to for giving linen a bright appearance, and is not sufficient to tint the paper. If the paper is to be blue laid, azure, or yellow wove, smalts is the colouring matter used. This is an indestructible blue, being cobalt glass reduced to extremely fine powder, and is used for the highest grades of papers, but many hand-made papers will be found to be coloured with ultramarine, which is a very good blue, but not quite so durable as smalts. Coloured papers require different additions, some in the form of powders or dry colours, others in chemical solutions, which by combination produce the desired colour in the pulp. When thoroughly mixed, the pulp is let down to the stuff chests and kept in constant motion by revolving paddles. The vat at which the paper-maker—the vatman—stands is kept supplied with pulp, diluted to a regular consistency, kept in motion by an agitator, and a constant temperature is maintained. The mould used is a wooden frame, strengthened by ribs across its width, and a wire top of laid or woven wire. In the case of laid papers the wires are laid side by side, tying wires about an inch apart are superimposed, and fastened to the laid wires by very fine brass wire. These wires make an indelible impression upon all paper made upon the mould, and distinguish laid from wove papers, the latter being made upon a woven wire mould. Watermarks are the results of designs in reverse fastened to the mould, the design being formed with wire upon the mould, or else an electrotyped mark is soldered to the mould.

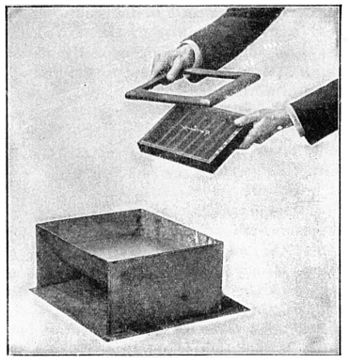

Watermarks may be simply small designs or lettering, or they may take the form of elaborate pictorial designs, but their purpose is to add distinction to the paper, and in some cases to prevent forgery of valuable notes or documents. Upon the mould is laid an open frame, known as the deckle, which serves to confine the pulp to the mould. For all papers two moulds are used in order to continue the cycle of operations uninterruptedly.

The vatman takes a mould, places the deckle upon it, dips the mould into the vat of diluted pulp, and lifts just the quantity of pulp necessary for the weight of paper being made. A slight shake is given to the mould, a small side shake and a greater shake backwards and forwards, something like the shake given to a type case, but less violent, the object being to cause the individual fibres to cross and felt together. The mould is kept perfectly level, or the sheets are thinner at one edge than at the others, the mould is pushed

along a support by the side of the vat, the deckle removed, and the operations of moulding repeated with the second mould.

The coucher who places the paper upon the felts ready for pressing, or couching, stands to the left of and facing the vatman. He takes the mould, stands it at an angle to drain, and places the mould face downwards upon a felt; the paper remains on the felt, and the mould is returned to the vatman. The felts are woollen cloths of close texture, resembling that of machine blankets, and are larger than the paper placed upon them.

Upon each sheet of paper a third worker places a felt, and the papermaking proceeds. When the pile of felts and paper is sufficiently high, it is transferred to a hydraulic press, and considerable pressure is applied in order to remove as much water as possible by squeezing, and, more important, to couch or press the fibres together and to close the sheets. The pile is removed, the felts taken out, the pile of paper given further pressing, and for some papers the paper is turned, rebuilt, and pressed again, to improve the closeness of the sheets. The paper is then taken to the drying loft, hung on ropes of cow hair, which material possesses the virtue of making no marks or stains upon the tender paper. Loft-drying is carried on at an even temperature, in order to permit of even shrinkage of the sheets. At this stage the paper, which is unsized, is known as waterleaf, and unless it is to be used in the unsized state, requires further treatment, as described in the next chapter, before being ready for use.

Mould-made papers are made by machine as far as making the sheets is concerned, other operations being carried out as for hand-made papers. The moulding or forming of the sheet is carried out in different ways on different machines, but the construction of the machines being kept secret by their users, it is not possible to give a description here.