Peking the Beautiful

PEKING THE BEAUTIFUL

An image should appear at this position in the text. If you are able to provide it, see Wikisource:Image guidelines and Help:Adding images for guidance. |

The Beautiful

Comprising seventy Photographic Studies of the Celebrated Monuments of China's Northern Capital and its Environs Complete with Descriptive and Historical Notes

By Herbert C. White Art Director Signs of the Times Publishing House, Shanghai Introduction By Dr. Hu Shih Celebrated Chinese Scholar, Philosopher, and Leader of the Chinese Renaissance The Commercial Press, Limited Shanghai, China Copyright, 1927, by The Commercial Press, Limited Printed in China To All Lovers of China's Glorious Artistic Heritage

the Monuments This Book is Dedicated An Acknowledgment

An image should appear at this position in the text. If you are able to provide it, see Wikisource:Image guidelines and Help:Adding images for guidance. |

THE author desires to express his indebtedness to the many friends who P have so kindly helped in gathering material, or who have otherwise assisted in the preparation of this volume. Special thanks are due Juliet Bredon, whose wonderful work on Peking first aroused an interest in, and a love for, the great historic monuments of the capital. Her kindly sympathy and valued suggestions in the make-up and plan of the present volume are greatly appreciated

The author is also indebted to Princess Der Ling for her enthusiastic encouragement in the production of this album, and for her sympathetic coöperation in the preparation and the revision of the captions. The many years spent with the Empress Dowager in the Forbidden City gives her an advantage as an authority on Peking which very few enjoy, and makes her suggestions and criticism of untold value.

Thanks are due Mrs. C. C. Crister for her kindly interest in the work, and for her valuable criticism of the text. Her long experience as editor and literary critic has made her assistance in the preparation of the manuscript of the utmost value; and also to Dr. Fong F. Sec, of the Commercial Press, who first conceived the idea, and encouraged the author to attempt the present production, and who has given the work its name.

Special credit is accorded the Commercial Press artists, Mr. C. Bockisch, Mr. F. Loebl, and Mr. F. Heinicke, who for more than a year have worked untiringly to produce a piece of art worthy of the city whose glory this volume seeks to portrag; and to Mr. A C. Liang, artist, whose excellent work in tinting the bromides for the color plates has added much to its beauty and interest

As a final word of appeciation, it is only fair to mention the fact that j. Herry White, twin brother of the author, has assisted him on all the numerous photographic expedi tions, and his enthusiastic cooperation and untiring ejorts have done much to make this volume a success. The beautiful study in full colors of the striking Porcelain Pailou of Confucian Temple fame was taken by him last spring by special request, to be used in the pages of this album. Introduction IN THE preface to her valuable work on Peking, Juliet Bredon makes the very modest remark that "a proper appreciation of Peking is not in the power of a Westerer to give, ... since it presupposes a thorough Z knowledge of China's past, an infinite sympathy with Chinese character and religions, an intimate familiarity with the proverbs and household phrases of the poor, the songs of the streets, the speech of the workshop, no less than the mentality of the literati and the motives of the rulers." While fully agreeing with these sagacious words, I wish to supplement Miss Bredon's observation by pointing out that the Western, visitor to Peking is often far more apprecia tive of its artistic and architectural beauty than are the native residents themselves. It is doubtless true that the Chinese resident loves Peking no less than does the Desterner, but search his heart and we shall find that he clings to Peking because of its fine climate and clear skies, or because of its spaciousness, or intellectual atmosphere. Few place its artistic beauty and architectural grandeur above these considerations. There are superficial reasons for this lack of appreciation on the part of the Chinese. The Imperial palaces and parks were for centuries forbidden places to the people, even to the high officials. Everywhere there were walls, and walls so annoyingly inconvenient that the people had to go out the norther gate in order to gain the southern gatel What the people could see every day were the decaying exteriors and red walls and yellow roofs which no longer had fascination for them. And the poets and the ment of letters of those Imperial days had no place for excursion and rendezvous in the city except the Tao-jan Ting, a deserted lonely arbor in the southern extremity of the city 1 Little wonder, then, that the people of Peking should be blind to architectural beauties that were never realities to them. But the real explanation lies deeper and touches the philosophical and artistic background of the nation The Chinese are a practical people, too much obsessed with utilitarian considerations to maintain a proper sense of appreciation for things beautiful in themselves but of little practical value Confucius was severely criticized by the Mo School for his emphasis on the importance of music and the dance, yet even Confucius was not free from shortsighted utilitarianism. In his eulogy on the great legendary King Yü, he paid a special tribute to his virtuous act of "living in shabby palaces but devoting all resources to drainage and flood prevention" Natural enough, there grew up legends which pictured the great kings Yao and Shun as reigning in houses with thatched roofs and earthen doorsteps. And these examples of virtuous simplicity were frequently cited by scholar-ministers who fought against the architectural extravagances of the tyrants. The naturalistic philosophers (commonly termed Taoists), too, were against the development of the fine arts. Lao Tsū went so far as to condemn all culture as leading men away from the path of nature. To these philosophers, nature is everything, and art as anti-nature, is evil. True it is that this exaltation of nature against art has produced an art of its own kind. It has had great influence in producing the school of "nature poets" who sang the praise of the silent flowers and the eloquent brooks, of the grandeur of the mountains, and the majesty of the farmer and the weaver. And from the nature poets there arose the nature-painters,--the poetic landscape painters - who saw beauty and personality in the trees and rocks and gave expression to their own feelings and ideas through artistic presentatiou of the bits of nature that chanced to attract them, But just as the naturalistic philosopher finds himself most at home under thatched roofs and within faggot doors, so the nature artist draws his inspiration chiefly from the rugged rocks and weeping willows and majestic pine trees. Architectural beauty does not interest him and consequently architecture is not ranked as a fine art. It is merely the craft of the carpenter and the builder who cater to the vulgar pomposity of the rich and the powerful Native philosophical and artistic traditions, too, seem to conspire to ignore all architectural grandeur and splendor. And because of the attitude of indifference on the part of the artistic and intellectual classes (except in the matter of landscape planning), Chinese architecture has remained to this day the conventional craft of the building trade. Anyone who has studied the Ying Tsao Fa Shih ( ), a compendium of architectural methods and designs first published in 1103, will realize that Chinese architecture has undergone practically no change during these centuries and has never advanced beyond the empirical tradition of the practicing craftsmen. The artists dis dainfully ignore it, and the utilitarian Confucianist scholar often regards it as an economic extravagance which smelt the blood of the people. The architectural grandeurs of Peking, to-day, are they not judged from this traditional standpoint? The Summer Palace, for instance, is remembered by many as something for which the wicked Empress Dowager once squandered the twenty-four million taels originally appropriated for the construction of the new navy. The truly splendid Pan Chan Lama Memorial, which Juliet Bredor ranks as the best example of modern stone sculpture in the vicinity of Peking (page 49 of the present collection), is regarded by the Chinese observer as nothing but a most extravagant monument of essentially foreign architecture, dedicated to the memory of the barbarian chief of a vulgar religion. And what is the Great Wallthe greatest of the Seven Wonders of the world, but the theme throughout the ages that has called forth a thousand plaintive and protesting songs that bemoan the tragic fate of its numberless and nameless slave-laboters and condemn the wars and territorial ambitions that necessitated its building and rebuilding To the Western visitor, all these artistic and moralistic prejudices ate a thing apart He, on his first arrival, falls in love with Peking. He is delighted with its red walls, its variegated shop signs, its beautiful lotus ponds, its gigantic cypresses-above all with its architectural splendors. He eagerly applies at his legation for permission to visit the temples and palaces, which until very recent years were closed to the general public Soon he is exploring the Dinter and the Summer Palace, the Hunting Park, the temples in, and far beyond, the Western Hills. Later he is tramping the Great Wall and the Ming Tombs. Soon he is looking for a house in which to settle down. He has "done" Peking, but cannot pull himself away from this City Beautiful. He must study further into these architectural glories which Religion and Power and Wealth have created. Such an ardent admirer of Peking is the author of this album of Peking the Beautiful. Mr. Herbert C. White, art director of the Signs of the Times Publishing House in Shanghai, arrived in this city in 1922, and shortly after joined his brother in Peking for language study. Both the brothers confess that they fell deeply in love with Peking from the first day of their arrival. During their one year of language study, they spent every holiday and every moment of spare time in exploring the great monuments and places of artistic and architectural interest. In that year they made seven hundred photographs of Peking and its vicinity. Since taking up his duties in Shanghai, Mr. White has returned to Peking every summer. His collection of photographs has now grown to three thousand, and it is from this vast collection that the present album of seventy pictures is selected. In 1925, two of his photographs were awarded first prize by the Henderson Photographic Competition : these now for the first and last plates of the present volume. Beginning with a Graflex camera, Mr. White has constantly studied the difficulties which he has had to encounter in photographing objects insufficiently lighted, or views too distant or too wide in range for the ordinary camera. Through sheer love of the art, he has gradually equipped himself to meet all kinds of emerqency situations. The strikingly beautiful picture on page 87, showing the palaces with the marble bridges, would have been impossible without the aid of a special lens. And the almost miraculous effect of the view of the Drum and the Bell Tower taken from the high White Dagoba (page 41) is only made possible by the use of unusual equipment Several of the views in this collection have already become records of history. The marble remains of the Benoist Fountain in the Yaan Ming Yuan shown on page 33, for example, have now disappeared from the scene where they were photographed. The Yuan Ming Yuan-of which the Jesuit Father Benoist wrote in 1767: "Nothing can com pare with the gardens, which are indeed an earthly paradise" – was destroyed in the war of 1860. Its glory is now preserved only in the records left to us by Benoist, Attiret, and others who visited it. What a pity it is, that of this earliest monument of combined architecture of the East and the best, so small a fragment is recorded by the modern art of photography) . I am convinced that such a collection of pictures of Peking as appear in this volume will not only serve the purpose of introducing or further endearing Peking to its Western friends, but will also help to teach the Chinese people to put aside their traditional prejudices and learn to admire and appreciate the monuments of Peking as a most valuable part of their artistic heritage. Let us forget the crimes that were committed in the palaces: forget those great ministers and censors of the Ming dynasty who died under the bastinado in the Imperial courtyards; forget the naval appropriations spent by the late Empress Dowager on her pleasure resort; and be thankful for the fact that after all something beautiful has survived the naval defeats and even the dynasty itself. Let us ascend the Pai Ta in a tranquil mood and allow our thoughts to transcend the hideousness of the Tantric religion and go back to those beautiful tales of Queen Hsiao (or was it Lady Liy) for whom her Tartar Emperor built the Dressing Arbor on that glorious Golden Island And let us forget, for the moment at least, all the woes and wait ings of the people around us and lose ourselves in appreciative contemplation of Peking the Beautiful.

HU SHIH

Shanghai, China, November 20, 1927. Preface

PEKING, for ages the center of art and culture, the pride of an ancient and glorious civilization, has within its crenelated walls the best that China has ever produced in literature, art, and architecture. To appreciate China, therefore, one must first see Peking. To have seen Peking is to have seen something far more than a mere town inclosed by mammoth walls. The great Northern Capital possesses individuality. It radiates an atmosphere that is "different." It is like nothing else on earth, and that is in itself a rare merit. In this city, with its ancient monuments, some of which date back nearly two thousand years, we find at once a picture and a history of all China in miniature. True, the historic monuments, unused and neglected, are fast falling into decay; but this ruin, which greets us at every tumn, pitiful as it really is, seems only to enhance the romance of this mysterious and once all-powerful metropolis. The greatness, the vastness the glory of such celebrated places as the Forbidden City, the Temple of Heaven, the Great Wall, or the Summer Palace, grips the imagination and holds one spellbound and humble before these emblems of an ancient and glorious past. For a long time there has been a recognized need for an album on historic Peking that would embody a representative set of all the important monuments of the capital. The very fact that so many of the ancient landmarks-priceless in their age-old glory-are being torn from their foundations and ruthlessly destroyed, makes an album of this kind not only interesting as an art volume, but a work of immeasurable value to China and to the world, as an authentic record of picturesque Peking. In the preparation of this volume it was recognized from the first that it should be as different as possible from any previous publication on Peking, so that it might not compete with, but add to the splendid contributions which have already been offered by others. Therefore, in the selection of photo-studies for Peking the Beautiful, the aim has been to present the ancient Chinese capital to the public in a new and entirely different setting. The photographs shown are the result of five years of tireless effort on the part of the author to reveal, through the medium of pictures, the charm and greatness of the capital, as revealed in its wonderful historic monuments. His collection of over three thousand photographs on Peking have been drawn upon for the material, and it has been the determination of the publishers to reproduce these as true to life as it is possible to make them. Photogravure-the only perfect medium of photographic reproduction-has been used in the printing of the monochromes, and of these there are fifty-eight. Of all the art books thus far produced in China, no attempt has been made to show the beauty and charm of the wonderful coloring of palaces and shrines. In the present volume the difficult and expensive task of presenting Peking in all the glory of its mar velous coloring has been accomplished, for twelve of the photographic studies have been reproduced in full and natural colors-a triumph which in itself makes this work absolutely distinctive. The album is also unique in that each of the seventy pictures is supplemented by a brief descriptive and historical sketch: that the reader, though a stranger to Peking, may learn to appreciate something of the grandeur of its conception, the greatness of its historic past, the wealth of its artistic heritage, and through contemplation of these venerable relics of a distant age, gain a keener insight into, and a better appreciation of, "things Chinese"; that those of our friends who are visiting the capital for the first time may not feel utterly lost as they wander through Forbidden City courts, and Throne halls, or stroll beside the rippling waters of the Summer Palace Lake; and that those who have seen Peking, or better still have lived within the circle of her mysterious gray arms, may be reminded of the happy days spent in the quest of romance and adventure both within and without her walls. Unfortunately, many difficulties have been encountered in the preparation of the "story" of the monuments. Accurate historical data in China is rare; especially that concerning the Imperial monuments and pleasure gardens for from these the people and even the officials have ever been kept apart, and much interesting information, gleaned from our guides and other "authorities" on Peking has later been found to be false, the vagaries of over-imaginative minds. Abandoning these sources of information, then, the author has turned to more reliable fountains, and the material presented herewith is largely that which he has succeeded in gathering from the information of others who, by long experience in the country and accurate knowledge of the language, have succeeded in arriving at the facts concerning this great monument or that. In the preparation of these captions the author is greatly indebted to Juliet Bredon for the wealth of information gleaned from the pages of her notable work, Peking, of which every friend of China should possess a copy. Much help has also been received and quotations freely made from the works of such noted Sinologues and specialists in various lines as Dr. W. A. P. Martin, Princess Der Ling, S. Dells Williams, A, E. Grantham, G. E. Hubbard, and L Newton Hayes; and these friends of China and lovers of Peking deserve credit for all of a literary nature that is excellent within the pages of this volume. Without doubt, some inaccuracies and discrepancies have inadvertently crept into its pages, and for these, we crave the indulgence of our readers; but if in spite of its faults the present volume should serve to introduce, or further endear, Peking to its Western friends, or should help Chinese and Westerners alike to a fuller appreciation of the wonderful "artistic heritage" bequeathed to the present generation in these priceless and venerable monuments of the Northern Capital, the purpose of this volume will have been fully met.

H.C.W. Page:Peking the Beautiful.pdf/19 Page:Peking the Beautiful.pdf/20 PEKING THE BEAUTIFUL Morning Sunlight on the Great Wall

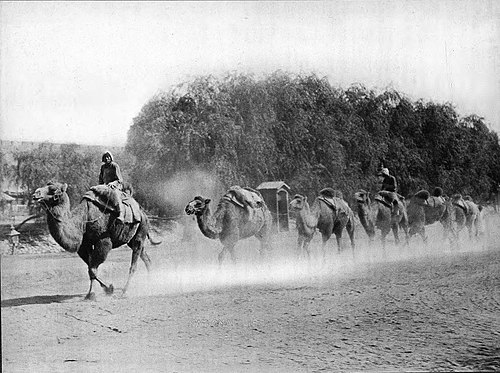

OF ALL the historic monuments scattered over the face of the erstwhile Celestial Kingdom, Rone enjoy such world-wide and age-old rep utation and prestige as belongs to the Great Wall of China. In comparison with this, the other famous sights of the country sink into insignificance. To many the world over, "China" and the "Great Wall" 3 are geographical terms equally well known. What the pyramids are to Egypt, the Great Wall is to China, a symbol that has made this country famous. It is with an unusual and indefinable thrill of expectancy, then, that the lover of antiquity purchases for the first time his ticket to the Great Wall! Boarding the train at old Hsi Chih Mên - Peking's westeramost gate--a modern train soon whisks us from the fertile plains, with their waving fields of kaoliang, past the old frontier city of Nankow, up. up into the very heart of the hills of Chihli. As our engine slowly puits up the narrow Nankow Pass - that remarkable Thermopylae fifteen miles in length which forms the northwestern gateway into China-the steep bare hills rise higher and higher. Soon "we leave behind us the last little farms, so stony that it seems impossible for industry to wrest a living from such poor soil. Walls curving down into the cañon and watch towers standing like sentinels give a picturesque sky line to mountain profiles, Scarred with the traces of many battles between the Chinese and the nomads, these subsidiary defenses of the Pass, which now seem purposeless and disconnected, send fancy roaming back to the days when they were vitally important in keeping out the ancestors of the Turks, the Huns, the Khitans, the Nüchens, the Mongols, and other barbarians who tried to fight their way into the coveted plains of North China" It is but an hour's climb from the walled city of Nankou to the little station of Ching Lung Ch'iao, or "Bright Dragon Bridge," and from here it is only a few minutes' walk along the ancient and rocky caravan road to the famous Pa Ta Ling Gate on the Dall. Nowhere along its winding course of fifteen hundred miles is the Great Wall more im pressive, nowhere more sublime, than here in the heart of the rugged mountains of Chihli. To see the wall at its best one must climb to the summit above the Pass; and there, in all their age-long glory, the giant battlements may be seert stretching of into the distant horizon as far as the eye can reach, now dipping into valleys, now climbing high on mountain sides resplendent with the glory of the ages,

The accompanying plate shows an unusually beautiful section of the wall as it "wanders along the crests of the hills" above the Nankou Pass, "scaling peaks which it seems impossible even the foot of man could climb. The massive loops of historic masonry are doubly impressive in these mountain solitudes," For a detailed description and historic sketch of the Great Wall, see paqes 70 and 112.

WALLS, walls, walls-nothing but walls ! This is one's first impression of Peking. These walls which at first give one such queer feelings WAV of imprisonment soon become symbols of protection, and give to the A TEX dwellers within the massive gray arms "a soothing sense of security." Bigger and broader and higher than the walls of any other city, the giant battlements that surround the capital are still the chief glory of this grand, old, medieval fortress. During the thousand years which have elapsed since Peking first became master of China the city has existed under many different names, and perhaps has been surrounded by as many different walls. "After each disaster her walls have been changed and her houses rebuilt, so that to-day she stands upon the debris of centuries of buildings." of the very earliest we know little, but fairly accurate accounts have been left us of the more recent walls. The noted Venetian traveler, Marco Polo, in his romantic description of the thirteenth-century Peking, writes thus : "As regards the size of this city, you must know that it hath a compass of twenty-four miles, for each side of it hath a length of six miles, and it is foursquare. And it is all valled round with walls of earth which have a thickness of full ten paces at bottom, and a height of more than ten paces; but they are not so thick at top. for they diminish in thickness as they rise, so that at top they are only about three paces thick And they are provided throughout with loop-holed battlements, which are all whitewashed. "There are twelve gates, and over each gate there is a great and handsome palace, so that there are on each side of the square three gates and five palaces, for (1 ought to mention) there is at each angle also a great and handsome palace, in which are kept the arms of the city garrison." To-day we find the walls just as they were in the time of the Mings. The present north vall was erected by the first Ming emperor, Hung Du, who later transferred his capital to Nanking: and his son, Yung Lê, rebuilt the other three sides in 1419. Towering fifty feet above the streets of the Manchu Tartar City, sixty feet thick at the bottom, and forty feet wide at the top, these roble battlements form what is undoubtedly the "finest wall surrounding any city now extant" Nine gates pierce the walls of the Nei Chiêng, as the Tartar City is called, and each of these is surmounted by an imposing tower. In these were kept the implements of war, and here were stationed the brave garrisons.

Our photo shows the famous "Fox Tower," which guards the southeast comer of the wall. The peculiar name has been derived from the popular belief that it is haunted by the spirit of a fox, "for whose ghostly comings and goings its doors are left open." The great fortress is here seen reflected in the waters of the moat, which completely encircles the city. For a further description of the walls and towers, see paqes 24 and 136.

東南城角之狐仙樓

ALMOST midway between Peking and the Western Hills -out and away from the whirl and bustle of the great"Northern Capital"—there lies a lovely paradise of pleasure. Ideally situated on the sides of a tiny mountain, amid the rare beauties of nature, the New Summer Palace stands to-day in almost undiminished splendor, a lasting monument to the artistic sense and skill of the Chinese people, The popularity of this spot through so many ages has been due principally to the presence of the famous Jade Fountain, only a mile or so distant, from whose cool depths there flows a constant and copious stream of the purest water. Around this crystal stream from age to age numerous palaces have been erected- the summer homes of the Imperial family. After the flight of the royal family and the destruction of the Old Summer Palace in the war of 1860, this beautiful place was abandoned. The Yüan Ming Yuan, as it was called, has never been rebuilt, and for more than twelve years the Imperial Court was without a summer residence. As Tzu Hsi, the Empress Dowager, began to advance in years, however, she longed for a quiet retreat from the strict formalities and routine of the Forbidden City, and so determined to build a summer residence near the site of the Old Summer Palace ruins. From the first she met with opposition. But this did not worry her. Furthermore, her private purse was empty; but that did not detain her in her purpose. She solved this difficult problem quite characteristically by appropriating the 24,000,000 taels set aside by the government to build a modem Chinese navy, for the erection of her "dome of pleasure," and on her sixtieth birthday, the Dan Shou Shan was ready for occupation. Our photo-study shows the beautiful entrance gateway, or pailou, that fronts the Summer Palace lake, and leads from the marble landing-place past two huge bronze guardian lions into the secluded recesses of the Pan Yün Tien, a group of lovely palaces surrounded by red walls and capped by a massive pagodalike temple. This handsome pailou is an elaborate wooden structure elegantly carved with extraordinary richness and variety of design. The delicate tracery of its numerous panels blends beautifully with the wealth of color on lacquered pillars and dragon-mounted beams. Those old court painters were lavish with color. Red, yellow, blue, gold, and green predominate, but these stronger tones are carefully blended with more subtle hues, and transform this archway into a thing of living beauty. The colorful eaves with their wealth of omamentation are surmounted by a glowing, glittering mass of Imperial yellow

glaze. This forms the roof, and caps the whole with a triple crown of never-fading glory. [See paqes 38, 46, 58, 80, 90, 94, 104, 110, 118, and 130.]

頤和園之雲輝玉宇坊

A GOLDEN island on a golden sea - such, according to popular legend, is this most beautiful of all the famous pleasure grounds of the capital. The Pei Hai is one of three charming artificial lakes known as the San Hai, or "Three Seas," which run from the north to the south along the entire western section of the Imperial City. The three lakes, which are supplied with water from the famous Jade Fountain in the Western Hills, date back to the days of the Great Khan, and are over a mile in length. In and around these lakes, are to be found some of the most beautiful objects and spots in the capital. Here for more than six centuries the great monarchs of China have built their domes of pleasure, and here by the rippling waters of the lake have they carried on their lordly revelries. The famous "Jade Rainbow Bridge," with its nine arches of chiseled marble, spans the waters of the Chung Hai, and separates the Pei Hai from the Chung Hai and the South Sea Palace. From this marble bridge the view is one of surpassing loveliness. At our feet lie the sparkling waters of the beautiful "North Sea," its banks shaded by groves of trees, while here and there float lotuses, "lazily grand, with their dense growth of leatherlike leaves and solitary blossoms rising above them in majestic isolation the very ernbodiment of the drowsy summer air, the very essence of repose." Spanning these quiet waters, and connecting the "Golden Island" with the mainland. is a graceful marble bridge, with a picturesque pailou on either end Beyond these, rising tier upon tier, are the glittering, multicolored roofs of temples and palaces; while above all, and overshadowing all, like a great "phantom lotus bud in the sunshine," with its lofty spire reaching up into the blue done of the sky, rises that mighty monument, the Pai Ta, or White Dagoba This massive pagoda, which crowns the "Hill of Gold," is among the most conspicuous as well as the most interesting of Peking's famous landmarks, and the whole gorgeous scene, as reflected again in the quiet waters of the lake, forms a never-to-be-forgotten picture-one so impressive that for centuries this landscape has been regarded by the Chinese as one of the "eight famous sights" of Peking.

The White Dagoba, standing on the ground of still older structures, was erected in A.D. 1652, in honor of the Tibetan pontiff who came to Peking to be confirmed in the title of Dalai Lama. But centuries before, in the days of the Liaos, a famous temple also crowned the beautiful hilltop. This huge monument is unlike most of the Chinese structures in shape, having a large, round, unomamented base, surmounted by a tall slender spire which ends gracefully in a gilded ball. This form of tower, so common throughout Mongolia and Tibet, symbolizes by its five sections."base, body, spire, ornament, and gilded ball- the five elements, earth, water, fire, air, and ether." For a further description of the Pei Hai, see paqe 62.

北海之堆雲積翠坊

BETWEEN the Nei Chêng, or Tartar City, on the north, and the Wai P E R Chêng, or Chinese City, in the south, we find two of the finest specimens of purely Chinese architecture in the capital - the huge Ch'ien Mén, or "Front Gate" and its adjoining tower. This imposing outer gate, here shoum in all its splendor, is built on the site of a five-hundred-year-old Ming structure, which was burned by the Boxers in 1900. A jew months later the inner tower also caught fire and was reduced to ashes. "The Chinese, fearful of ill-luck overtaking the city, hastened to rebuild both towers, which are practically the only monuments in Peking restored since Chien Lung's time." The Chien Mên tower is a huge brick structure built along medieval lines. A broad double stairway leads from the once sacred lower court to the lofty terrace above. Shining balustrades of polished marble and massive double roofs of gleaming emerald tile add life and color to the drab-gray of brick and stone, and transform this gateway into a thing of life and beauty. Typical of all the other towers, it is ninety-nine feet high, which allows free and uninterrupted passage for the good spirits who soar through the air, according to the necromancers, at a height of one hundred feet" The great central doorway, the arch of which is just discernible above the tree tops, has for centuries been kept for the sovereign's use alone. No common feet were allowed to desecrate this sacred entrance. To-day, even though the imperial prerogatives have long since passed away, we still find the huge doors closed and barred; and the populace, quietly submissive to an age-old custom, uncomplainingly make their way around the mammoth pavilion Vithin recent years four wide passages have been pierced through the walls - two on either side of the inner tower. This has helped greatly to relieve the congestion of traffic between the south and the north city. The former single entrance was wholly inadequate for the traffic of a great capital's main thoroughfare. In former days the two towers were connected by high walls, semicircular in form, with the convex side facing the outer or south city. This wall with its outer tower served as a double protection to the inner gate that opens directly into the capital with its vast treasures and splendid palaces. Most of the gateways still retain this medieval feature, of which, within the last three decades the great "Front Gate" has been robbed

If one would see the street life of Peking, no better place could be fourd than this spot between the two towers of the Ch'ien Mén. This hot July morning finds the streets unusually quiet. Pedestrians a donkey, rickshas, a Peking cart, and last of all the modern tramcar make up the list of Peking's popular modes of travel. Besides these we find the common handcart with its human horses straining away under the load of heavy freight For a further description of Peking's walls and towers, see pages 18 and 136,

正陽門城樓

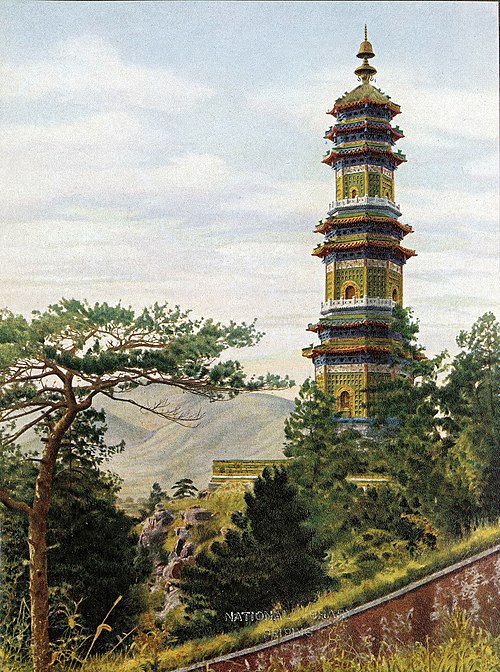

AN A TOT THE least interesting of the myriad monuments in and around old Peking ate its fascinating pagodas. Typically Oriental, and often occupying the most beautiful and prominent places in the city, these artistic spires add just the needed touch to fine vistas both within and without the walls. Aside from their artistic value as landscape dec the orations, these structures have a deep religious significance. According to tradition, the primary or original object of such towers vas to provide a "depository for the relics of Buddha's burnt body." but Confucianists still declare them to be important "regulators of 'feng shui,'or the 'influence of wind and water,' and they are supposed to bring peace to the cities and temples and tombs that lie within their shadow." All the Peking pagodas, some of which carry us back to a far-distant age, are of Indian origin, and they are usually found in the neighborhood of Buddhist temples and shrines. The two most noted pagodas within the city walls are the "Bottle Pagoda," and the "White Dagoba" in the Pei Hai These two splendid structures both show strong traces of Tibetan influence in their design. Materials that enter into the construction of pagodas differ widely, and there is also a vast range in shape and size. Some, such as the " Thirteen-Storied Pagoda" of Pa Li Chuang, are vast brick structures towering hundreds of feet above the plain Others, like the striking spire on "Jade Fountain Hill" are constructed entirely of stone; while dozens more, comparatively small, ače made of much costlier materials, such as marble, iron, or glazed-porcelain tile. Some miniature pagodas, sheltered within the walls of famous temples in the Forbidden City, are even made of bronze or cloisonné. Most of these interesting structures are tall spires containing seven divisions, each of which is surmounted by a curved roof of tile. Sometimes we find the magic "seven" broker into other odd numbers, such as nine or thirteen, but in the majority of cases the number "seven" is adhered to. The graceful Porcelain Pagoda, here shown in all the beauty of its green and gold encaustic tiles, is not located on a hilltop, as is customary, but on the sunny western slope of the Yu Ch'uan Shan, or "Jade Fountain Hill." Overlooking a very ancient temple ded icated to the Yü Wang, or "Rain King," its shining gilded dome points heavenward, while around its eight sides are hundreds of miniature niches, each of which provides a resting-place for a seated figure of Buddha. This pagoda with its myriad Buddhas fulfills to an almost superlative degree the real purpose of a pagoda; for its very name signifies an "Abode of Idols." This ornate little spire has been declared by Chinese writers to be "the loveliest of 20,000 pagodas which once existed in and around Peking," For other glimpses of these picturesque structures, see paqes 23, 49, 55, and t21,

Page 28

玉泉山瓷塔

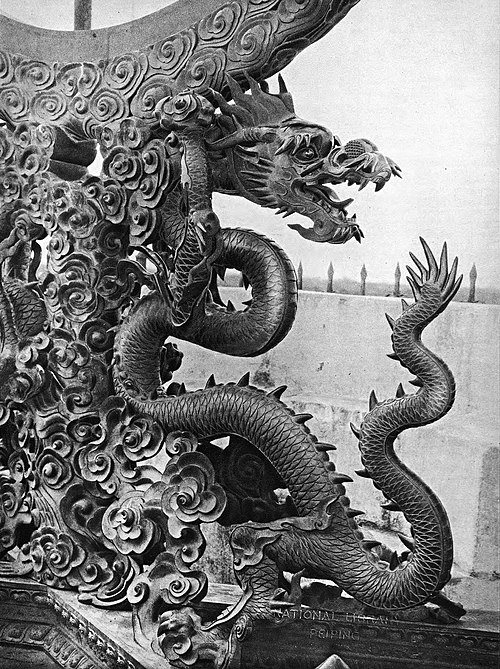

T R OM the earliest times the Chinese, like most Eastern people, have been interested in astronomy and astrology. For ages, the court astronomers have been men of the highest standing and were reverenced alike by Th e princes and people. The Imperial Almanac, which it was their duty to AS ) prepare, "was a publication followed, trusted, and reverenced as sacred os as scripture," and the observations it contained regulated every important act in the life of untold millions within the borders of the Celestial Kingdom. By all, froma the humblest subject, to the emperor on his gilded throne, its dictates were accepted without a question. The present observatory, or Kuan Hşiang Tai, as it is called, was established in Peking during the reign of Kublai Khan, in the year 1279, and is located on top of the city wall. In those ancient times it formed the southeast angle of the capital. But when Yung Lê, the first Ming emperor to establish his capital in the north, tore away the old Mongol wall in 1409, he extended the city south to the present line of the Hatamen and Ch'ien Meru At the same time he rebuilt and remodeled the old observatory on the wall. Native astrologers were put in charge of this National Observatory, and they made their calculations from huge bronze instruments of rather crude design. Later on, the Arabs were placed in charge, and they made all the observations for the official calendar until early in the seventeenth century, at which time the remarkable talent of Father Derbiest, a Jesuit missionary, was discovered by the court, and he was placed in charge. For many years Father Verbiest served as president of the Mathematical Faculty, and the Observatory was under his control until his death in 1688. Under his able direction, Many new instruments cast in bronze vere erected, and some others were brought over from Europe. With these new instruments, this famous missionary was able to introduce "Occidental science in mathematical circles in place of a semi-superstitious study of the four quadrants and the twenty-eight constellations of native science," For his distinguished services to the court and people of China, Derbiest was "granted a title of nobility and presented with a tablet," which is now preserved in the French legation. His connection with the Honorable Board, and his popularity at court, gave great influence, it is said to the Jesuit fathers who first settled in China. The beautiful dragon-wreathed instrument shoun in the plate opposite is undoubt edly one of the masterpieces cast by Chinese artisans under the direction of Father Derbiest. It is the most richly omamented instrument in the famous group that sur mounts the upper platform of the broad brick terrace on the wall. These fine old instruments are still consulted occasionally by students of astronomy from the government universities, and are at present under the care of the Department of Education.

Page 28

觀象臺方位儀

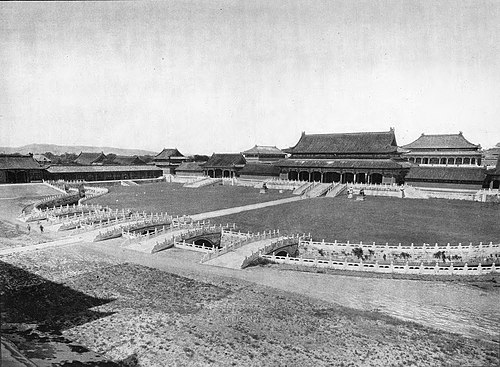

ITHIN the crenelated walls of old Peking we find to-day four distinct cities: the Tartar or Manchu City on the north; the Chinese City in the south; the Imperial City in the center of the Manchu City; and in the innermost heart of them all the Purple or Forbidden City, the one-time home of the emperor and his court From the marble terrace of the lofty White Dagoba one can get a most delightful view of the Forbidden City, with its acres of yellow tile gleaming like gold in the sunlight. This vast palatial domain is surrounded by six Chinese miles of massive pink walls, with a charming pavilion on each of the four comers, and a mammoth gateway on each side. The whole is surrounded by a broad moat The great doors of this mysterious Forbidden City have been closed to the public for centuries, and before the establishment of the Republic, sew from the outside world were permitted to enter its gilded halls. "What poetic suggestion in the very name of the city," exclaims Miss Bredon,"-a Forbidden City reserved for the Son of Heaven! The dignity of such a conception compels respect, doubly so when we consider all it represented the profound reverence paid to the Sovereign by the people of a great empire, the immense spiritual power in his hands, the tradition of his divine descent, the immemorial dignity of his office. To have seen this Forbidden City therefore is to have seen something much more wonderful than noble buildings, and to enter it is to feel the pulse of the ancient civilization which throbbed as mightily in the eighteenth century as ever in that dim past whereof these palaces them selves, though already old, are but a modern record" The approach to the Forbidden City is magnificent indeed. Splendid gates dot the wide imperial avenue as it leads from the great Ch'ien Mên, past the Legation Quarter, into the Imperial City. The huge T'ien An Mén, shown on the extreme right of the photo, guards the southern wall of the Huang Cheng. "Between the t'ien An Mên and the Du Men lies the outer part of the Forbidden City, subdivided by the Tuan Mén," the second from the right The third structure is the famous Wu Men, or Meridian Gate. This huge fortress is the "official entrance to the Forbidden City, and is the grandest of all the palace gates."

The T'ai Ho Mên is next in line, and leads directly into the great Court of Supreme Harmony. Beyond, in all their glory, stand the three principal throne halls. These mag nificent buildings are known as the San Ta Tien, and are arranged on a high marble platform, one behind the other. The first is the gigantic T'ai Ho Tien, or Throne Hall of Supreme Harmony: the second is the Chung Ho Tien; and the third is the Pao Ho Tien, which formerly was used as an imperial examination hall. The space immediately behind these until recent months has not been open to the public, having been reserved as a home for the deposed Manchu emperor and his court

禁城全景

ON THE outer, or southern, portion of the Forbidden City, almost midway between the Tien An Men and the lofty battlements of the Wa Men, stands the superb structure known as the Tuan Men - shown from 2 between the trees in the opposite plate. This quiet, enchanting spot is set be in the midst of a "series of immense paved courtyards divided one from the other by high and massive walls, above which are erected imposing pavilions with yellow-tiled, overhanging roofs, flanked by great towers built in the same style and similarly roofed with Imperial yellow." This huge pavilion and its courtyard constitutes one of seven such gateways that line the royal avenue-a half mile in length-between the great "Front Gate" of Peking and the sacred precincts of the "Purple City." This southern approach is the grandest and by far the most impressive of all the many fine approaches to temples and palaces within the walls of the capital-one eminently befitting the abode of a "Son of Heaven," and the sovereign of nearly one fourth of the human racel To most Westerners, a gate is merely a door. The word is not generally associated with architecture or great buildings. Not so in China! Here "a gate" often proves to be a vast monument -a masterpiece of architecture and Oriental art In the Imperial and Forbidden Cities these so-called gates rival in beauty of design and richness of omamen tation, even the finest of the palaces and throne halls. In China the Bible student leams to appreciate in a new way the descriptions of Eastern life and Oriental customs recorded in that most ancient of all books. Much of the detail of Bible stories, once hazy and obscure, are here made plain in the charming book of Esther we read of Mordecai the Jew, "who sat in the king's gate," and we pity the poor man, thus compelled to pursue his duties in the midst of the humble surroundings that the word "gate" suggests to the Western mind. But from China we see him sitting, not in a gate, but in the midst of regal splendor; with probably a palace at his disposall The Tuan Men is a lofty edifice, surmounting a massive red wall, which serves as its foundation. From the shining balustrades of polished marble to the peak of the gently stoping roofs of "golden" tile, this beautiful gateway is in a state of excellent preservation. The harmony in the rich Oriental decoration is perfect. The massive wooden pillars that support the roof, as well as the delicate tracery on windows and doors, are painted a rich maroon, while the eaves are elaborately decorated in shades of white, blue, green, and gold. Unfortunately the three huge passageways which pierce the walls of the foundation are hidden by the luxuriant foliage which adorn these outer imperial courtyards. For a further description of the gates and palaces of the Forbidden City, see pages 30, 50, 82, 80, 102, and 116. Page 32

端門

"A Palace That Has Lost Its Soul" O PILGRIMAGE to Peking is complete without a visit to the ruins of the Yüan Ming yvan, the once beautiful summer home of the emperors. For two centuries the pride of the whole empire, this paradise of pleas ure is to-day a heap of ruins. On every hand are mute evidences of the PAROL tragedly that war has wrought Exquisitely formed artificial hills are na row crowned by wrecked pagodas, picturesque valleys are filled with shattered pavilions, and lovely lotus lakes are spanned by broken bridges. Of the far famed island palace of a hundred rooms—"once the jewel of the domain"-naught remains save tottering walls and leaning balustrades. Were it not for the delightful pen pictures left us by Father Benoist and others who visited the palace grounds and assisted in the building of the five "yang lou" or foreign pavilions, we would know little of the former grandeur of the Yuan Ming Yian. Writing from Peking in the year 1767, Father Benoist gives a vivid picture of the Imperial surtimer home in the following words: "Six miles from the capital, the emperor (Ch'ien Lung) has a country house where he passes the greater part of the year, and he works day and night to further beautify it. To form any idea of it one must recall those enchanted gardens which authors of vivid imagination have described so beautifully. Canals winding between artificial mountains form a network through the grounds, in some places passing over rocks, then forming lovely lakes bordered by marble terraces. Devious paths lead to enchanting dwelling pavilions and spacious halls of audience, some on the water's edge, others on the slopes of hills or in pleasant valleys, fragrant with flowering trees which are here very common. Each maison de plaisance, though small in comparison with the whole inclosure, is large enough to lodge one of our European grandees with all his suite. That destined for the emperor himself is immense, and within may be found all that the whole world contains of the curious and rare a great and rich collection of furniture, omaments, pictures, precious woods, porcelains, silks, and gold and silver stuffs."

It was in the year 1737 that Chien Lung commanded Father Castiglione to build the five foreign palaces. These charming pavilions, built of the purest white marble and richly decorated, were the pride and delight of the emperor. In order to further beautify these costly mansions he thought of adorning them both inside and out with fountains. The talented and versatile Father Benoist was called upon to construct these fountains in spite of all his representations as to "want of knowledge." The sketck below shows all that remains of the celebrated fountain and water clock, which was once a masterpiece of sculpture and engineering. Many there are, of every nation, who mour the loss of this wonderful palace which was laid in ruins by the guns of the British and French in the war of 1860.

圓明園遺址

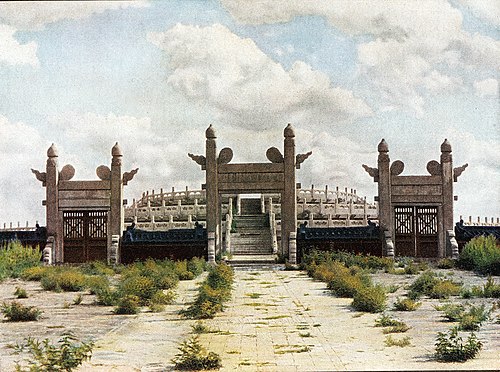

A Royal Cemetery N A VAST amphitheater formed by converging hills, which are supposed to bring all good influences to a focus, repose the ashes of thirteen emperors of the last Chinese dynasty." This beautiful cemetery, known as the Ming Tombs, lies a little more than ninety li from the gates of the capital, and is considered one of the most interesting sights in the vicinity of Peking. Emperor Yung Le, the second of the Mings, and perhaps the greatest statesman and builder that China has ever known, was the one who chose this enchanting spot as the site for his temple and tomb. Perhaps the most striking feature of these imperial tombs, which before the downfall of the Ming dynasty constituted "one of the largest and most gorgeous royal cemeteries ever laid out by the hand of man," is the magnificent approach more than three miles in length, designated in the Annals as "The Spirit's Road for the Combined Mausolea." This road begins with a massive memorial arch, which is here seen in all its beauty. The mammoth pailou, with its five exquisitely carved arches of polished marble, is over fifty feet high and more than eighty feet wide. It is said to be the finest and largest memorial arch in all China Through its wide portals we catch a glimpse of the long spirit avenue as it leads along through waving fields of kaoliang past graceful pavilions, over marble bridges, and up to the foothills that shelter this "vale of the dead" After passing the "Great Red Gate," we arrive at the "Tablet House," guarded by four marble "Pillars of Victory." Here we enter the "Triumphal Way," more than two Chinese miles in length. This royal road, paved throughout its entire length, is lined, as were the triumphal approaches of the Tangs and the Sungs, with attendant figures of men and animals. Beyond the last pair of kuge stone images, all of which have been cut from single blocks of marble, the road passes through the triple "Dragon and Phoenix Gate," and thence up the gently sloping hill that leads to the Mausolea, which are arranged in a vast semicircle, with the grave of Yung Le in the center,

The majestic sacrificial hall, where for centuries the rites of ancestral worship have been performed in his honor, is the largest building in China. Two hundred feet across the front, and one hundred feet deep, with its massive double roof of "golden" tiles supported by forty huge pillars sixty feet in length, this wooden structure has withstood the storms for five hundred years, and "looks as if it might brave them for a thousand more." Behind this hall is the graceful "Soul Tower," containing a large tablet of pink marble inscribed with Yung Le's posthumous title. Immediately to the rear of this tower is the artificial hill, more than a half mile in circuit planted with somber pines. "Beneath this is the huge doned grave chamber where Yung Le's coffin, richly lacquered and inscribed with Buddhist sutras, reposes upon its jeweled bedstead amid rich treasures of precious stones and metals."

明陵

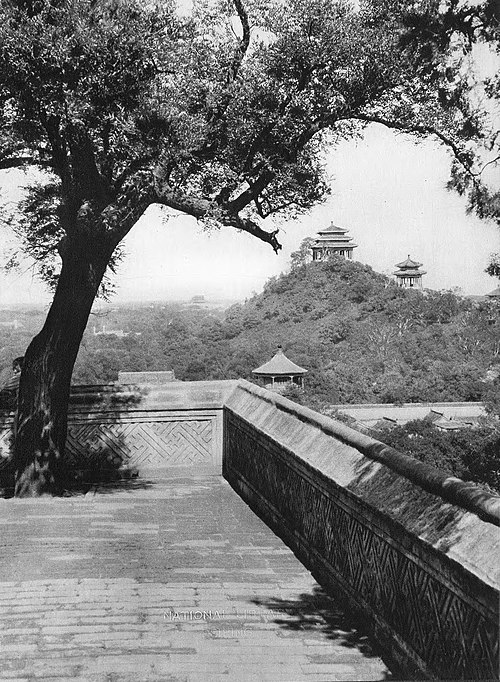

The Mountain of Ten Thousand Ages T is one of those delightful Oriental days in early spring. The warm April sun, half hidden behind fleecy clouds, mounts higher and higher as ve, on our pilgrimage to the Summer Palace, bid farewell to the massive gray walls of old Hsi Chih Men and enter the long winding avenue of weeping A willows that leads us on toward our goal. Twenty Chinese miles and more are covered before we near the Imperial summer home. Then in the distance a roof of gleaming tile, reflecting the rays of the morning sunlight, is seen, and soon, swinging around the last sharp bend and passing beneath a spreading wooden archway, we find ourselves in a spacious open courtyard. Here we are greeted by two huge, bronze, guardian lions. In days, not at all remote, when imperialism held sway in China, few save the Empress Dowager herself and a few court favorites were permitted to participate in the pleasures of this romantic spot; but now gates and doors formerly closed to the public are wide ftung on their hinges. Finding ourselves within the walls of the first inner courtyard, which is dotted with trees and rows of handsome statuary, we stand before an imposing structure formerly used by the Empress Dowager as her Imperial Audience Hall Here she met the great officials of state, and here she received the foreign diplomats and their wives. We can learn little of the grandeur of this fine hall, for, like most of the other pavilions within the palace grounds, its great doors are sealed, and only a peep here and there can be had through the heavily latticed windows. Passing this large throne hall, and tuming abruptly to the left we follow a winding pathway, bordered by flowering shrubs and trees, down to the shores of the lovely lake The scene spread out before us is enchanting. All that the lavish hand of nature could bestow, combined with the best that human art and skill could devise, seems here to be brought together to enrich the spot and make it beautiful Gardens and flowers, hills and groves, mountains and lakes, islands and bridges, temples and pagodas, in all their natural and artistic splendor, make a rare setting for the elegant verandahed pavilions and spacious courtyards which compose the Imperial summer home.

Skirting the whole northern end of the lake, the K'un Ming Hy, which is more than four miles in circumference, is a richly carved marble balustrade. From these marble terraces charming views can be had of the Dan Shou Shan and of the whole glorious landscape. Our photo-study shows the Summer Palace hill with its mammolh pagoda and other interesting temples and pavilions from a comer of this wonderful terrace. [See paqes 20, 46, 58, 68, 80, 90, 94, 104, 126, 118, and 130.]

萬壽山

The Drum and Bell Towers

OF THE many historic monuments spoken of by Marco Polo in his poetic description of the majestic city of Cambaluc, only a few remain to grace the modern capital of China. Perhaps the most noteworthy among these are the Bell and Drum Towers - two huge structures of Simposing proportions and design that still constitute the chief glory of the north city. Towering far above the surrounding homes of the people, and overshadowing even the most princely of the temples and palaces, for seven centuries these two veterans have played an important part in the lives of the dwellers within the walls. For many millions all down through the years, the very habits of life have been guided and circumscribed by the deep notes of that giant curfew and the thunder tones of the great drums in the tower. Here is what Marco Polo says: "In the middle of the city there is a great clock-that is to say a bell -- which is struck at night. And after it has struck three times, no one must go out in the city, unless it be for the needs of the sick; and those who go about on such errands are bound to carry lanterns with them." In the olden days, indeed, even until comparatively recent years, "when the curfew sounded from the Bell Tower, people went to bed." These two towers, facing each other, and not more than a stone's throw apart, are situated in a large open space almost midway between Coal Hill and the northern wall. In Mongol days they are said to have stood in the exact center of the city of the great Khan. The Drum Tower, as can readily be seen from the picture, is by far the larger of the two structures, being ninety-nine feet in height, and ninety-nine feet long. Its giant base, or terrace, is of brick plastered over with thick mortar and painted a deep red The upper portion is of wood, also painted a rich vermilion. The whole is surmounted by a double roof of glittering emerald tile, supported by giant pillars nearly forty feet high. Sixty-nine stone steps of rather uncomfortable proportions lead from the base of the tower to the immense upper hall, where the three great drums are kept—the largest one in the center, and a smaller one on either side. On this large central drun the watches of the night were struck.

la former days this tower also contained a clepsydra, or water clock,"consisting of four vessels, one below the other; water trickling from the highest to the lowest moved an indicator which showed the hour," thus giving the time to the whole city. From the lofty porches, a superb view can be had of the city and its environs. The graceful Bell Tower contains one of the large bells cast in the days of Yung Lê, which weighs over 23,000 pounds. This distant view of the two towers, with the Pei Hai, or "North Sea," in the foreground, was taken from the base of the White Dagoba, another monument that carries us back to the days of Mongol grandeur. For a further description of the Bell Tower, see paqe 148.

鐘樓與鼓樓

The South Sea Palaces

U ST outside the walls of the Forbidden City on the west are to be N R K found a group of beautiful gardens and palaces. These less formal halls and dwelling pavilions, nestled in among the trees that border the shores of the Nan Hai, were erected by the old emperors as a winter resort-a conveniently close yet quiet retreat from the strict formalities of the Court and the more or less strenuous routine always adhered to within the walls of the "Purple City." The usual approach to these delightful Winter Palaces is by the Hsin Hua Men on the south, an Imperial gateway, two stories high, which more nearly reserables a palace than a gateway. It was built, we are told, by Ch'ien Lung, who prepared it for his favorite Mohammedan concubine, so that she might gaze across the street at the mosque that had been erected especially for her, but which custom prevented her from entering. "As soon as we pass through the gateway, a radiant vista stretches before us. At our feet lies the Nan Hai, or 'Southern Sea,' with the fairy island of the Ying T'ai [Ocean Terrace) floating on it, and beyond, the stately succession of Winter Palace roofs shining in the sunlight." Near by is the Imperial boathouse where are kept the ponderous barges, which to this day "are pressed into service to convey guests across the lake when the President gives a garden party." Having been invited by His Excellency Li Yuan-hung to attend one of these Presi dential parties, we find the stately boats all in readiness, and are soon gliding smoothly over the rippling waters of the lake toward beautiful "Ocean Terrace," a corner of which is shown in the opposite plate. Here in this little fairyland, under the green canopy of trees, with charming pavilions and fascinating rockeries on every hand, we pause for a few moments to listen to the quiet lapping of tiny waves-waves, which with every ripple seen to whisper some telltale story of Peking's Tomantic past--days of barbaric splendor, and nights of lordly revelry, when great warriors like the splendid Khan feasted with a thousand of his lords; or of later days and nights when the Nan Hai gardens were filled with light, music, and laughter as the Empress Tzū Hsi carried on her splendid revelries.

In the midst of all this concentrated beauty, a pathetic touch is added by the memory of the unfortunate Emperor Kuang Hsü, who for years was kept a prisoner here, and who died an exile in his palace shortly after the Court returned to Peking in 1902. The room is shown us where he died--a small alcove chamber very much like the usual Chinese sleeping apartment, but richly furnished, and with the unusual addition of a large plate glass window. Here the frail, melancholy prisoner might look out on "his little world of beauty," and mourn over his lonely, forlom condition- an emperor, born to rule, but all his life ruled over, until death released him from his mental and physical sufferings

南海瀛臺

Temple of the Five Towers

ISITORS, motoring to and from the capital along the far-famed avenue of to weeping willows, pause in their journey along this charming highway to view at close range a strange, pagodalike structure, half hidden behind groves of ancient cypress and pine. Standing a little more than a li S e from the road, almost midway between the sparkling waters of the SC K'un Ming Lake and the gloomy battlements of old Hsi Chih Men, this ruined remnant of past splendor lifts its lonely towers above the tombs and princely sepulchers that dot the western suburb of the capital. The Du T'a $să, or "Five-Pagoda Temple" as this odd monument is called, shows strong traces of Indian influence; in fact, it is supposed to be an exact copy of the ancient Indian Buddhist temple of Buddhagaya Juliet Bredon, in her monumental work Peking gives a fascinating glimpse into the picturesque history of this six-hundred-year-old shrine, which once bore the impressive title of "Great Perfect latelligence Temple." Her story is as follows: "In the early part of Yung Le's reign, during which time a new impetus was given to the intercourse between China and India, a Hindu 'sramana' of high degree came to the Chinese capital and was received in audience by the emperor, to whom he presented golden images of the five Buddhas and a model in stone of the diamond throne, the 'vajrasana' of the Hindus, such being the name of the memorial temple erected on the spot where Sakyamuni attained his Buddhahood. In return the emperor, himself the son of a Buddhist monk, appointed him state hierarch, and fitted up for his residence the 'True Bodhi' temple to the west of Peking (founded during the preceding Mongol dynasty), promising at the same time to erect there a reproduction in stone of the model temple he had brought with him, as a shrine for the sacred images. The new temple was not, however, finished and dedicated until the reign of Cheng Hua, according to the marble slab set up near it, and inscribed by the emperor for the occasion. This specifically states that in dimensions as well as in every detail the Wu T'a Ssŭ is an exact reproduction of the celebrated diamond throne of central India. Only the five pagodas from which the temple takes its name remain, standing on a massive square foundation whose sides are decorated with rows of Buddhas. Worshipers and objects of worship-all have vanished. The priests are gone and the site is utterly abandoned save for the occasional visit of a hurried tourist."

The imposing terrace, which forms the base of the tower, is constructed entirely of pink marble and stands about thirty feet high. The group of five marble pagodas that surmount it are approximately twenty feet in height, and are engraved with Hindu characters and adorned with seated figures of noted Buddhist disciples. For a description of other Peking monuments bearing traces of Indian influence and design, see paqes 22, 48, and 98

五塔寺

A Thousand-Colonnade Walk

NDOUBTEDLY the most fascinating spot in all Peking is the lovely Yi Ho Yuan, or "Garden of Peaceful Enjoyment." Formerly known as Un the Wan Shou Shan, it was renamed thus by Her Imperial Majesty, a Tzū Hsi, who rebuilt and beautified it during the later years of her long regency. The Empress Dowager was an artist to her verg finger-tips; and in this quiet spot by the lakeside, where nature so kindly lends itself to art, she gave full expression to her innate sense of the beautiful In all Chinese art three things predominate. They are always there-mountains, trees, and water. Without these three no picture is complete. Thus, in the forest-covered Dan Shou Shan, or "Mountain of Ten Thousand Ages," with the sparkling waters of the K'un Ming Lake playing at its feet, the artist soul of the great Empress found a hapen of rest from the duties and cares of state. Here she could lavish untold millions without regret in an effort to adom and make it still more beautiful The Imperial summer homes overlooking the water "are massed in a townlike group at the northern end of the lake One, double-storied," belonging to the emperor, "Jaces a vied across the lagoon that even a sovereign was lucky to command. "The Empress Dowager's quarters, further on, also give directly onto the lake with special landing stages whose balustrades are curled into sea foam, and coiled into dragons. These apartments, like all Chinese palaces, consist of a series of verandahed pavilions connected by open corridors built around spacious courts." In the summer time these courtyards, brilliant with flowering shrubs and trees, laden with sweet perfume, were roofed over with "honey colored matiings, thus transforming them into cooloutdoor living rooms like Spanish patios." From the Empress Dowager's quarters there extends a gorgeous covered walk, decorated with hundreds of pictures showing various scenes within the Summer Palace grounds. This colorful promenade, mounted on its terrace of chiseled stone, follows the Marble balustrade the full length of the northern end of the lake. Dinding past lovely pavilions and graceful marble bridges: fronted by dazzling pailous and artistic marble landing-places, this cool inviting walk terminates at the famous "marble boat." From end to end this picturesque structure is bordered by majestic cypress trees and inlaid paths of stone

Our plate shows a ting section of this gorgeously decorated promenade, the long line of which is broken at frequent intervals by graceful pavilions. These not only served to break the monotony of the lakeside scene, but also afforded frequent resting places where Her Majesty might stop and refresh herself with a sip of tea, with naught to break the evening stillness save the lapping of silver-capped waves ont marble shores. See paqes 20, 88, 58, 88, 80, 90, 94, 104, 116, 118, and 130.]

頤和園長廊

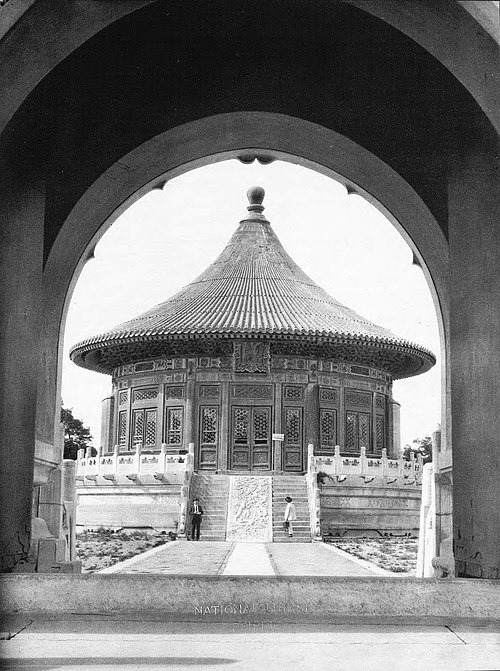

The Pan Chan Lama Memorial

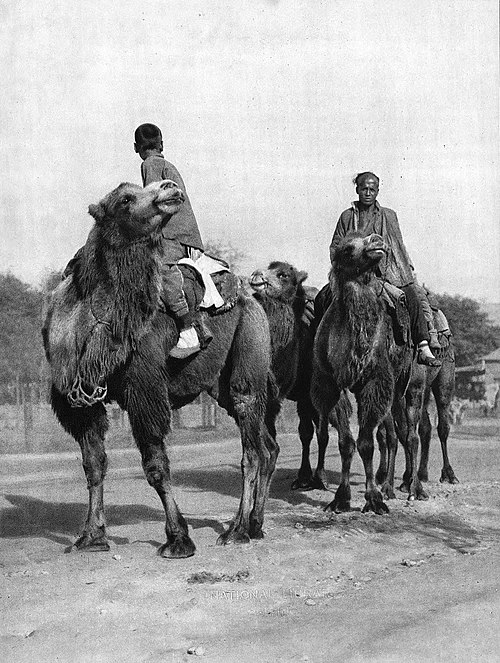

WAT Z ITHIN the secluded walls of the famous Huang Ssă, a Buddhist monastery two miles north of Peking, there stands to-day the most remarkable and perhaps the finest monument in all China --the Pan Chan Lama Memorial. This splendid marble cenotaph, which is shown in the opposite plate, was erected by the emperor Chien Lung in honor of the Pan Ch'an Lama, one of the "Living Buddhas" from Tibet, who contracted smallpox while on a visit to the emperor, and died in his palace near Peking in the year 1780. The "Son of Heaven," anxious to prove his devotion to the Lama faith, and eager to retain the friendship of the Mongol monks, placed the body of the holy man in a golden coffin and sent him back to the Dalai Lama in Tibet. The emperor then proceeded to prepare a second precious casket in which were placed the infected garments of the saint, and over this was erected the beautiful white marble stupa, to stand as a perpetual memorial to the life and labors of this illustrious priest. As we leave the protecting towers of old Anting Mên, and wend our way northward over the dusty plain toward the massive walls of this ancient Buddhist monastery, with its temple roofs of yellow tile gleaming like gold in the sunlight, we follow in the footsteps of thousands of faithful devotees who for centuries have come here "to gaze with reverent awe and place their votive offerings before the temple shrine." As we stand with silent worshipers beneath the shadow of this proud monument, with its massive proportions, its exquisite sculpture, and its golden crown, in its picturesque setting amid shady groves of cypress and pine, we are deeply impressed with the rare ability of the Chinese sovereigns to choose the sites for their temples and shrines, "so that the beauties of nature should enhance the work of the religious architect."

"No better example of modern stone sculpture exists near Peking," says Juliet Bredon, "than this pinnacled memorial modeled oa Tibetan lines, adhering generally to the ancient ladian type but dijering in that the dome is inverted. The spire, composed of thirteen steplike segments symbolical of the thirteen Buddhist heavens, is surmounted by a large cupola of gilded bronze, and the whole monument, with the four attendant pagodas and the fretted white pailous, is raised on a stone and marble terrace. From its wave-patterned base to the gilded ball thirty feet above, it is chiseled with carvings in relief, which recall the Mongol tombs and palaces in Agra and Delhi, and on its eight sides we find sculptured scenes from the life of the deceased Lama--the preternatural circumstances attendant on his birth, his entrance to the priesthood, combats with heretics, instruction of disciples, and death A pathetic note is given by the lion who wipes his eyes with his paw in grief over the good man's passing. All this carving is unusually fine with extraordinary richness of Omanentation." For a further description of the Huang Ssū, or "Yellow Temple," see paqe 122.

黃寺石塔

DHROUGH the medium of architecture the old emperors of China have s from the earliest times sought to empress upon the minds of their subjects the sacredness of the Imperial prerogatives. Thus we find in the history of the Chinese capitals that vast significance was attached to the emperor's palace, and all that pertained to it. Occupying the central portion of the Tartar City, the "Forbidden City" of Peking has been famous for many centuries. Marco Polo in describing the palace of that early day says: "You must know that for three months of the year, to wit December, January, and February, the Great Khan resides in the capital city of Cathay, which is called Cambaluc, In that city stands his great Palace, and now I will tell you what it is like "It is inclosed all round by a great wall forming a square, each side of which is a mile in length; that is to say, the whole compass thereof is four miles. This you may depend on; it is also very thick, and a good round. At each angle of the wall there is a very fine and rich palace in which the war hamness of the Emperor is kept, such as bous and quivers, saddles and bridles, and bowstrings, and everything needful for an army. Also midway between every two of these Comer Palaces there is another of the like, so that taking the whole compass of the inclosure you find eight vast Palaces stored with the Great Lord's hamess of war." Much that is grand in the conception and plan of the wonderful Forbidden City, we owe to the hardy space-loving Mongols, but to Yung Le, the mighty builder of the most noteworthy palaces and temples of Peking, we are indebted for the Forbidden City as it stands to-day. "The famous Du Mên, or Meridian Gate" (see opposite plate), is the official entrance to the inner Forbidden City, and is the grandest of all the palace gates." This huge fortress-like structure, with its five massive towers, is second only to the great Throne Hall itself in beauty of line and massive splendor. The unusual photograph shown herewith was taken from the pretty "terrace walk" which surrounds the courtyard. Through the huge central archway the Emperor passed on his journey to and from the palaces. At such times his coming and going was announced to all by the deep-toned bell in the tower above.

This glorious Itaperial arch was also frequently used for other important state occasions. Here the Emperor went out to meet his conquering armies, and here the prisoners that they brought were presented to him. "Here too," writes Juliet Bredon, "the presents he conferred on vassals and ambassadors were pompously bestowed, and the calendar for the whole empire distributed at New Year."

午門

The Eastern Hill Temple

IS New Year's morning in Old Cathay, and Peking, the proud capital, is

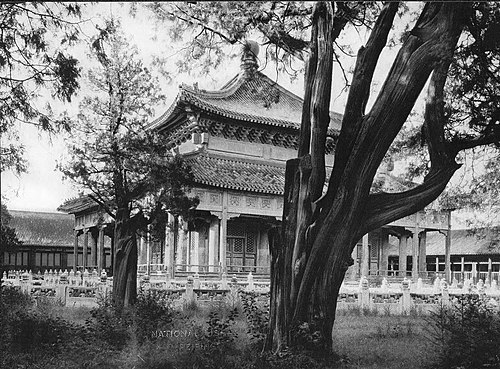

dressed in gayest holiday attire. As the sun rises above the eastera horizon her people may be seen wending their way along the broad street toward the city gate. They pass through the old Chi Hua Men and join the eager, expectant throngs who press on toward a common goal De join the procession, and after a brief ten-minute walk approach a temple entrance, imposing even for Peking. Four wooden pailous, arranged in a quadrangle, mark the spot by the roadway, which, for more than ten centuries, has been a temple site. Two stone lions, one on either side, guard the outer gateway, while cords of fragrant incense, piled high on tables all about us, meet with an ever-ready sale. De enter and find the spacious courtyards teeming with life and activity; for, within these outer walls, an old-fashioned fair is in progress, and the numerous bazaars present a galaxy of flaming Oriental color. Passing through the massive gateway, we enter the sacred inner court. Here we are surrounded by thousands of reverent worshipers performing their devotions, while clouds of incense rise from countless brazen urns that dot the spacious porticoes. The Tung Yüeh Miao, or Eastern Hill Temple, as this rich sanctuary is called, is one of the best examples of a Taoist pantheon to be found anywhere in China. It is very old, and some of the more popular images carry us back to a remote age. The temple buildings, ROW standing upon the site of still older structures, date back to the Mongol dynasty (A.D. 1260-1368). In the center of the courtyard, approached by an elevated causeway of chiseled stone, stands the main hall or temple, which is beautifully shown in the accompanying plate. Here, where "shadows meet and whisper and shrink back into deep warm darkness," sits the deity who, in the Taoist hierachy, ranks "almost on a level with the Creator," namely, the Spirit of T'ai Shan, China's holy mountain in Shantung.

Near "Him Vho Rivals Heaven," in a comer of this same sanctuary, we find the famous god of writing, "to whom all those desirous of succeeding in literature bring their offerings of pen brushes and ink slabs." The lesser shrines of the Tung Yüeh Miao are filled with a multitude of gods-"mostly those who control the mortal body. Persons sufering from various ailments come here to propitiate the gods of fever, of chills, of coughs, of con sumption, of colic, of hemorrhage, of toothache: for gods exist governing 'every part of the body from the hair to the toenails.' To make assurance doubly sure, the sick include in their pilgrimage a visit to the famous brass horse in one of the shrines behind the main wall, which can cure all the maladies of men." This temple, with its spacious courtyards, dotted with handsome pavilions and row upon row of glistening marble tablets, interspersed with fine old trees, is one of the most attractive of Peking's numerous shrines.

東嶽廟

H E STORY of Peking would remain only half told were we to forget the glorious range of mountains that encompass it on the west and on the north. These far-famed Western Hills form the outer bul | S w arks of a huge sierra "which separates the plain of northeast China from the Mongolian Plateau, and stretch back over a hundred 30 miles to the Gobi Desert." But why are the Western Hills so intimately associated with Peking and her age-old prestige as the center of the world's oldest and most populous empire? The place chosen for the site of the capital seems to be an odd one indeed. "Tucked away in this northert comer of the empire," comments G. E. Hubbard, "far from sea or river, and farther still from the centers of population and wealth which congregate on the Yangtze, it seems a strange position for the old emperors to have chosen. The key to the mystery lies, how ever, in these very hills and the mountains lying beyond, which through all the centuries have been the bulwark of China against her principal enemies. The threat of Tartar and Mongol invasion was so persistent till modern times that the only safe place for the sovereign power of China was here close behind the barrier which separated it from the dreaded 'hordes.' The strategic center lay at the focal point of the great amphitheater of moun tains which commanded the exits of the various passes, and from which the tribesmen, if they broke through, could be attacked in force before they were clear of the foothills." Behind the outer ridge of the Western Hills the "ranges mount gradually to a series of peaks 4,000 to 5,000 feet, possessed of a ruggedness of outline which gives them a grandeur out of all proportion to their actual height. Along the sky line, invisible from the capital except through powerful glasses, runs the Great Wall of China." In these Vestera Hills, twenty miles and more from the capital, we find the famous Imperial Hunting Park. Here, amid the rugged yet beautiful surroundings of these fascinating hills, the old emperors gave themselves up to the joys of the chase, and here from age to age they erected fine temples and splendid pagodas. Within the walls of this ancient hunting park, "which runs like a huge coil of rope flung across ridge and valley," and set in the midst of fine groves of cypress and pine, is the beautiful spire known as the "Hunting Park Pagoda" In ages past it used to grace the entrance to a fine old temple, but all traces of this sanctuary have vanished, and now only the ting, tinkling bells, drooping like pomegranates from green and gold pagoda eaves remain to tell us of past glories of the chase. The lower portion of this interesting old "Idol Tower"- the part constructed of brick and mortar-is fast falling into decay, but the encaustic green and gold tiles of the upper portion are as bright and as fresh as though constructed only yesterday.

西山御苑寶塔

The Hall of the Great Perfection