Picturesque Nepal/Chapter 10

CHAPTER X

THE ARTS OF THE NEWARS—Continued

The Nepalese School—Its Origin and Influences—Metal-work—Metal Statuary—The Process of Manufacture—The Artist-priest—Minor Metal-work—The Makara—Religious Utensils—Wood-carving—Terra-cotta—Stone-carving—Textiles.

METAL STATUE OF RAJA BHUPATINDRA MALL, DURBAR SQUARE, BHATGAON.—Pages 71, 156.

The highest forms of Nepalese art are represented by two different methods of expression—painted pictures and metal statuary. In the Valley itself, for reasons which are not quite clear, specimens of the former craft are not numerous, although the State Library at Katmandu possesses a small collection which is most instructive. It demonstrates that in the art of picture-painting the old artist-priests of the Valley produced work of a very fine order, and this was no doubt the foundation on which was built the better-known banner-painting of the Tibetan monasteries. But it was in the plastic arts, especially in their manipulation of metals, that the Newar craftsmen excelled, and it is this aspect of the æsthetic that gave Nepal in the old days its artistic reputation. The sculptured portraits of its nobles, the life-size statues of its kings, the dignified bas-reliefs of its saints, and the noble conceptions of its gods, executed in hammered brass or cast copper, show, besides a profound knowledge of artistic principles, an earnestness of purpose, and intensity of feeling, which must impress all who see this work at its best. A study of the Newar's handiwork in this direction will reveal an acquaintance with the best traditions of his subject; and an attainment of a superior plane of art work, which give the productions of this comparatively small country a more than ordinary interest.

To properly appreciate the art of the Newar metal-worker, one must see a statue in copper-gilt of a Newar king on his high stone colunm, surrounded sometimes by a group of smaller members of his family, and in the picturesque architectural setting of the Dubar square. Seated or kneeling, in a dignified attitude, usually with hands clasped, from the height of his monumental pillar he gazes down calmly and serenely on the city that he ruled, and on the temples that he caused to be built. It is doubtful whether any country in the world has conceived a more artistic memorial statue than those to be observed in the public squares of the cities of Nepal. The well-proportioned stone pillar, some 40 feet in height, severe in its simplicity, stands firmly on the flagged pavement supported by a solid stone base. Surmounting this is a lotus capital—the symbol of purity and divine birth—and around this is entwined a snake, the emblem of eternity. Then comes the massive throne of metal-gilt, on the back of embossed lions, elephants, and dragons, bound together by boldly executed foliage, among the conventional branches of which sport animals, birds, and fishes, each having its special attribute. The statue is shaded and protected by a golden umbrella, hung with little tongues of metal which tinkle in the breeze; or it may have a canopy of Naga snakes or huge cobras, whose expanded hoods form an ideal background to the whole. Here and there to give lightness to the conception a metal bird or reptile is poised, standing out from the remainder of the design, a little touch of delicate art-feeling which indicates that the maker of these statues was an artist to his finger-tips. The Newar metalworker played with his stubborn material as a modeller manipulates clay with his fingers, and the ease with which he twisted and turned his copper or brass, and chased the little figure on its surface or applied the flower-bud there and the lizard here, indicates the thought of the master-mind and the touch of the master-hand. Much of the distinctive character in this work lies in the freedom in which the metal is handled, and the combination of the two different processes of hammering and casting in the same artistic composition. The Newar craftsman conceived his design, and proceeded in the most workmanlike manner to materialize it in the metals at his command, melting, embossing, and riveting the various portions, separately forging the dagger, chasing the bracelet, and engraving the finger-ring, thus building the whole up according to his approved original idea. The result of this is a work of art which will stand every test, and is perfectly satisfying in all respects. The figure itself, regarded as a portrait, is broadly treated, and seems to reproduce the general character of the sitter, while the features appear to have been studied from life, but conventionalized in order to be in conformity with the entire scheme.

Apart from these public statues which adorn the streets and squares of the cities, the courtyards of the temples often contain portrait figures in metal, of people of lesser degree, works of considerable artistic merit and no little interest. They represent founders or benefactors of the sacred edifice, and vary in size according to the practical interest these bygone individuals have shown in its foundation. In front of the principal entrance to the shrine may generally be seen a large group, often protected by a substantial cage of forged iron, so closely constructed as to cause an investigation of its contents a matter of no little difficulty. These are the portraits of the founder and his wife, and are regarded by all with great respect, almost approaching worship. In some few cases these are actually saints or deities, but the ordinary custom is to place in front of the shrine metal images of the distinguished laity who have been intimately identified with its establishment. Around these are grouped smaller statues, also portraits, and in front of each is a shallow receptacle for incense or oil and wick. These are likenesses of those who have contributed their moiety to the glorification or upkeep of the temple, or depict devotees who have dedicated a figure, a bell, or some sacred utensil, to be added to its furniture.

The method employed by the Newar in building up his larger statues is a somewhat unusual one, as he obtains his result by the combination of two distinct technical processes. His smaller work is cast in the well-known cire-perdue manner, literally, the "lost wax," and technically, the "waste mould," method of casting. Parts of his larger

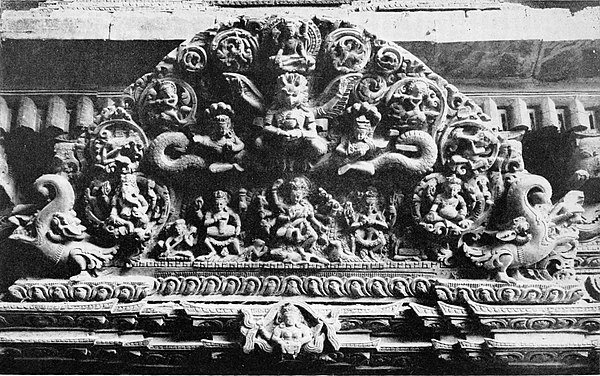

ELABORATE WOOD-CARVING ON BHAIRAN TEMPLE AT BHATGAON.

WOOD-CARVING OVER DOORWAY AT KATMANDU.

In the lower flights of his artistic fancy the Newar metal-worker has also recorded some very fascinating ideas, and his guardian lions or aggressive dragons placed in front of his buildings are often very spirited in feeling. Some of these for size alone are fine pieces of workmanship, and show the Newar to be a thoroughly honest craftsman, proud of his skill. His purely ornamental effects are, moreover, freely designed, and display a love of nature and a fondness for floral forms which are in keeping with the temples they serve to decorate. Flowers are a great feature of the Newar ritual, as they are of most religions of the East. A quotation from an old work, attributed to the Prophet Mahomet, and often referred to by followers of other creeds, may explain one of the reasons of this—

"If you happen to possess one pice

Keep it for buying your daily bread;

But if you are the fortunate possessor of two,

Then spend half to buy a flower.

The fruits and rice sold in the bazaar

Are only to pacify our bodily wants;

But a flower will pacify the Thirst of the Soul,

And it is the only nectar in this Universe."

STEPS OF THE NYATPOLA DEVAL, OR THE TEMPLE OF THE FIVE STAGES, AT BHATGAON.

The lowest of these colossal statues are two wrestlers, the historic giants of the Newars, supposed to have ten times the strength of ordinary men.

FOUNTAINS IN THE GARDEN AT BALAJI.—Page 179.

Of what may be termed the minor arts of Nepal, that of the worker in wood is the most important, and in his productions this craftsman has been even more prolific than the metalworker. But he has rarely if ever aspired to statuary in this material, although his caryatid struts are at times such wonderful figure groups that they may almost be classed as fine art. But regarded broadly the Newar woodworker has subordinated his handiwork and utilized it mainly in conjunction with the architect, so that his conceptions come within the category of the applied arts. In his carved tympanums—those large characteristic panels applied over all Nepali doorways—the woodworker has been allowed considerable latitude, and these features are often complete pictures, religious subjects sculptured out of wood, and treated with a freedom which adds not a little to their charm. The motive of these "overdoors," whether in wood or in metal, is ordinarily the same general idea—a story in the centre depicting a mythological incident, or a pictorial arrangement of various deities, while around the whole in high relief is displayed a kind of traditional convention of Garuda, Makara, Nagas, and ornament, nearly always composed on the same general lines. A picturesque detail, and one on which the Newar woodcarver delighted to show his skill and versatility, is the afore-mentioned roof-strut, supporting the wide overhanging eaves of the pagodas. The broad roofs of these buildings naturally threw deep shadows, and the duty of breaking up this dark mass with some light and graceful design was left to the artistic devices of this craftsman. This individual conceived the idea of converting these constructive elements into figures of deities provided with many arms, and the problem was solved in a most satisfactory manner. The light catches on these fanciful figures with their outspread arms, and the heavy appearance of this shadow is at once corrected, and an artistic and picturesque effect attained. But this is only one of the many clever contrivances invented by the Newar woodworker to overcome constructive difficulties of a like nature. That useful element in sound building, the wooden lintel, is a special characteristic of Nepalese architecture, and the decorative treatment of this forms an important feature of the style. A masonry composed of a good red brick flashed with a kind of half glaze, and bound with beams of sal timber, is the manner in which the builder carried out his work in the days of the Newar kings, and over this sensible solid framework the metal and wood worker were allowed to bring their artistic fancies into play, with a result in every sense satisfying. This structural device of the lintel, as used in connection with the doors and windows, gives the buildings of Nepal their distinctive character, and the particular beam above and below the window, treated in the Newar manner, is the keynote of the whole design. Foliated and elaborated, moulded and corbelled, this constructive element was the joy of the woodcarver, who brought all his artistic energies to bear on its embellishment. The consequence is that the window, in Nepalese buildings, has rarely received more ornate treatment in the history of art, and in the decoration of this single feature the Newar has proved himself a versatile designer and a finished craftsman. To add to its richness, he has also devoted his cunning to devising innumerable patterns of lattice-work with which to fill in the open space of the window, and a study of these alone is a field in itself. The screen-like effect is obtained by dovetailing together small pieces of wood, and the variety of combinations produced by the Nepal workman is endless. It is, of course, the mushrebiyeh of Cairo and the pinjra of the Punjab, but the patterns in the windows of the Newar houses are considerably more elaborate than those designed by the Arab or the Sikh. This very attractive form of window screen, enabling the occupant to "see and not to be seen," is ordinarily supposed to have been invented by the Mussulman, with a view to securing air combined with privacy in his zenana, but the exuberance of this lattice-work in Nepal indicates its possible origin in a country where the Crescent was never carried. Owing to the method of construction the patterns employed in this art are fundamentally geometrical, but the Newar has been able to add foliated forms to these, and, by superimposing floral shapes in wood and metal, has carried this joinery to its utmost limit. A living interest is still taken in this effective form of lattice-work, and one special design on a building in Bhatgaon is pointed out with pride to this day as the only specimen of its kind in the whole of Nepal.

In conjunction with the carved woodwork, moulded brick and modelled terra-cotta is often found, the eave-mouldings and watercourses over the doors and windows being generally constructed in this manner. The builder used an exceptionally good quality of clay, and by means of a system of firing which produced a hard, smooth, shell-like surface, his masonry seems to defy all weathers, besides displaying a most artistic colouring. But apart from these structural features, terra-cotta is used freely for purely decorative purposes. The tympanum, which is found over most important doorways, usually of hammered brass or carved wood, is in cases boldly executed in burnt clay with the details sharply modelled in this plastic material. Niches with figures, dragons, and foliage, running borders of snakes, finials of crowing cocks, and all the ornamental additions characteristic of a brick architecture are to be observed, while one curious accessory to many of the temples, also in terra-cotta, smacks not a little of Celestial influence. This is a small figure of an elephant, spiritedly modelled in clay, and usually placed in a position occupied by a flower-pot, for out of a hole in its broad back sprout bulbous plants, displaying a most quaint effect. Terra-cotta is sometimes used in place of wood or metal for the sake of economy, and in place of the metal lamp hanging in front of a building, this takes the form of a similar article in burnt clay, exactly the same design being followed by the potter in his material as employed by the metalworker in producing his brass casting.

Except in a few instances, the stone-carving of the Newar craftsman is not quite of the high quality as shown in his wood and metal work. For some reason, which is not immediately evident, he did not seem at home in this material, and usually his figures are archaic in character, his dragons limp and wanting in vigour, while his ornament is heavy, and lacks feeling. His architecture, when executed in stone, is not so open to these adverse criticisms, the various features such as the columns, capitals, mouldings, and niches being executed in an artistic and workmanlike manner, but the higher flights of fancy, as for instance his figure-work, compare unfavourably with his pictorial ideas expressed in other mediums. Nevertheless, in some examples this material has been very cleverly manipulated, a frieze continued around two stories of a temple in the Patan Durbar, and representing in lithic pictures a complete epitome of one of the Hindu epics, being a wonderful piece of stone-carving in miniature, and there are a few others almost its equal.

In textiles Nepal is singularly deficient, and except for the common cloth of the country, little or no weaving is undertaken. Certain woven and embroidered fabrics find their way into Nepal, but they are obviously of Chinese or Tibetan origin, and it does not seem that the Newars were ever in sympathy with this art. The more masculine materials of wood and metal were the favourite mediums of this craftsman, and with these he has left records in the Nepal Valley which show that he was one of the most gifted artists of his time.

The submerged statue of Narain at Bajali.—Page 181.

The head which alone rises above the gently flowing waters is surrounded by a canopy of snakes' heads.