Popular Science Monthly/Volume 19/July 1881/The Races of Mankind

THE

POPULAR SCIENCE

MONTHLY.

JULY, 1881.

| THE RACES OF MANKIND.[1] |

By E. B. TYLOR, F. R. S.

ANTHROPOLOGY finds race-differences most clearly in stature and proportions of limbs, conformation of the skull and the brain within, characters of features, skin, eyes, and hair, peculiarities of constitution, and mental and moral temperament.

In comparing races as to their stature, we concern ourselves not with the tallest or shortest men of each tribe, but with the ordinary or average-sized men who may be taken as fair representatives of their whole tribe. The difference of general stature is well shown where a tall and a short people come together in one district. Thus, in Australia the average English colonist of five feet eight inches looks clear over the heads of the five feet four inch Chinese laborers. Still more in Sweden does the Swede of five feet seven inches tower over the stunted Lapps, whose average measure is not much over five feet. Among the tallest of mankind are the Patagonians, who seemed a race of giants to the Europeans who first watched them striding along their cliffs draped in their skin cloaks; it was even declared that the heads of Magalhaens's men hardly reached the waist of the first Patagonian they met. Modern travelers find, on measuring them, that they really often reach six feet four inches, their mean height being about five feet eleven inches—three or four inches taller than average Englishmen. The shortest of mankind are the Bushmen and related tribes in South Africa, with an average height not far exceeding four feet six inches. A fair contrast between the tallest and shortest races of mankind may be seen in Fig. 1, where a Patagonian is drawn side by side with a Bushman, whose head only reaches to his breast. Thus, the tallest race of man is less than one fourth higher than the shortest, a fact which seems surprising to those not used to measurements. In general, the stature of the women of any race may be taken as about one sixteenth less than that of the men. Thus, in England a man of five feet eight inches and a woman of five feet four inches look an ordinary well-matched couple.

Not only the stature, but the proportions of the body, differ in men of various races. Care must be taken not to confuse real

Fig. 1.—Patagonian and Bushman.

race-differences with the alterations made by the individual's early training or habit of life. A man's measure round the chest depends a good deal on his way of life, as do also the lengths of arm and leg, which are not even the same in soldiers and sailors. But there are certain distinctions which are inherited, and mark different races. Thus, there are long-limbed and short-limbed tribes of mankind. The African negro is remarkable for length of arm and leg, the Aymara Indian of Peru for shortness. Negro soldiers standing at drill bring the middle finger-tip an inch or two nearer the knee than white men can do, and some have been even known to touch the knee-pan. Such differences, however, are less remarkable than the general correspondence in bodily proportions of a model of strength and beauty, to whatever race he may belong. Even good judges have been led to forget the niceties of race-type and to treat the form of the athlete as everywhere one and the same. Thus, Benjamin West, the American painter, when he came to Rome and saw the Belvedere Apollo, exclaimed, "It is a young Mohawk warrior!" Much the same has been said of the proportions of Zooloo athletes. Yet, if fairly-chosen photographs of Caffres be compared with a classic model, such as the Apollo, it will be noticed that the trunk of the African has a somewhat wall-sided straightness, wanting in the inward slope which gives fineness to the waist, and in the expansion below which gives breadth across the hips, these being two of the most noticeable points in the classic model which our painters recognize as an ideal of manly beauty.

In comparing races, one of the first questions that occurs is, whether people, who differ so much intellectually as savage tribes and civilized nations, show any corresponding difference in their brain. There is, in fact, a considerable difference. The most usual way of ascertaining the quantity of brain is to measure the capacity of the brain-case by filling skulls with shot or seed. Professor Flower gives as a mean estimate of the contents of skulls in cubic inches—Australian, seventy-nine; African, eighty-five; European, ninety-one. Eminent anatomists also think that the brain of the European is somewhat more complex in its convolutions than the brain of a negro or Hottentot. Thus, though these observations are far from perfect, they show a connection between a more full and intricate system of brain-cells and fibers, and a higher intellectual power, in the races which have risen in the scale of civilization.

The form of the skull itself has been to the anatomist one of the best means of distinguishing races. It is often possible to tell by inspection of a skull what race it belongs to. In comparing skulls, some of the most easily noticeable distinctions are the following:

When looked at from the vertical or top view, the proportion of breadth to length is seen as in Fig. 2. Taking the diameter from back

Fig. 2.—Top View of Skulls. a, Negro, index 70, dolichocephalic: b, European, index 80, mesocephalic; c, Samoyed, index 85, brachycephalic.

to front as 100, the cross diameter gives the so-called index of breadth, which is here about 70 in the negro (a), 80 in the European (b), and 85 in the Samoyed (c). Such skulls are classed respectively as dolichocephalic, or "long-headed"; mesocephalic, or "middle-headed"; and brachycephalic, or "short-headed." A model skull of a flexible material like gutta-percha, if of the middle shape, like that of an ordinary Englishman, might, by pressure at the sides, be made long like a negro's, or by pressure at back and front be brought to the broad Tartar form. In the above figure it may be noticed that while some

Fig. 3.—Side View of Skulls. d, Australian, prognathous; e, African, prognathous; f, European, orthognathous.

skulls, as b, have a somewhat elliptical form, others, as a, are ovoid, having the longest cross diameter considerably behind the center. Also in some classes of skulls, as in a, the zygomatic arches connecting the skull and face are fully seen; while in others, as b and c, the bulging of the skull almost hides them. In the front and back view of skulls, the proportion of width to height is taken in much the same

Fig. 4.—a, Swaheli; b, Persian.

way as the index of breadth just described. Next Fig. 3, which represents in profile the skulls of an Australian (d), a negro (e), and an Englishman (f), shows the strong difference in the facial angle between the two lower races and our own. The Australian and African are prognathous or "forward-jawed," while the European is orthognathous, or "upright-jawed." At the same time the Australian and African have more retreating foreheads than the European, to the disadvantage of the frontal lobes of their brain as compared with ours.

Fig. 5.—Female Portraits. a, Negro (W. Africa); b, Barolong (S. Africa); c, Hottentot; d, Gilyak (N. Asia); e, Japanese; f, Colorado Indian (N. America); g, English.

Thus the upper and lower parts of the profile combine to give the faces of these less civilized peoples a somewhat ape-like slope, as distinguished from the more nearly upright European face.

Let us now glance at the evident points of the living face. To some extent feature directly follows the shape of the skull beneath. Thus the contrast just mentioned, between the forward-sloping negro skull and its more upright form in the white race, is as plainly seen in the portraits of a Swaheli negro and a Persian, given in Fig. 4. On looking at the female portraits in Fig. 5, the Barolong girl (South Africa) may be selected as an example of the effect of narrowness of skull (b), in contrast with the broader Tartar and North American faces (d, f). She also shows the convex African forehead, while they, as well as the Hottentot (c), show the effect of high cheek-bones. The Tartar and Japanese faces (d, e) show the skew-eyelids of the Mongolian race. Much of the character of the human face depends on the shape of the softer parts—nose, lips, cheeks, chin, etc.—which are often excellent marks to distinguish race. Contrasts in the form of nose may even exceed that here shown between the aquiline of the Persian and the snub of the negro in Figs. 4 and 6. European travelers in Tartary in the middle ages described its flat-nosed inhabitants as having no noses at all, but breathing through holes in their faces. By pushing the tips of our own noses upward, we can in some degree imitate the manner in which various other races, notably the negro, show the opening of the nostrils in full face. Our thin, close-fitting lips differ in the extreme from those of the negro, well seen in the portrait

Fig. 6.—African Negro.

(Fig. 6) of Jacob Wainwright, Livingstone's faithful boy. With the purpose of calling attention to some well-marked peculiarities of the human face in different races, a small group of female faces (Fig. 5) is given, all young, and such as would be considered among their own people as at least moderately handsome. Setting aside hair and complexion, there is still enough difference in the actual outline of the features to distinguish the negro, Caffre, Hottentot, Tartar, Japanese, and North American faces from the English face below.

The color of the skin, that important mark of race, may be best understood by looking at the darkest variety. The dark hue of the negro does not lie so deep as the innermost or true skin, which is substantially alike among all races of mankind. The negro, in spite of his name, is not black, but deep brown, and even this darkest hue does not appear at the beginning of life, for the new-born negro child is reddish-brown, soon becoming slaty-gray, and then darkening. Nor does the darkest tint ever extend over the negro's whole body, but his soles and palms are brown. The coloring of the dark races appears to be similar in nature to the temporary freckling and sunburning of the fair white race. On the whole, it seems that the distinction of color, from the fairest Englishman to the darkest African, has no hard and fast lines, but varies gradually from one tint to another.

The natural hue of skin farthest from that of the negro is the complexion of the fair race of Northern Europe, of which perfect types are to be met with in Scandinavia, North Germany, and England. In such fair or blonde people the almost transparent skin has its pink tinge by showing the small blood-vessels through it. In the nations of Southern Europe, such as Italians and Spaniards, the browner complexion to some extent hides this red, which among darker peoples in other quarters of the world ceases to be discernible. Thus the difference between light and dark races is well observed in their blushing, which is caused by the rush of hot red blood into the vessels near the surface of the body. The contrary effect, paleness, caused by retreat of blood from the surface, is in like manner masked by dark tints of skin.

The range of complexion among mankind, beginning with the tint of the fair-whites of Northern Europe and the dark whites of Southern Europe, passes to the brownish-yellow of the Malays, and the full brown of American tribes, the deep-brown of Australians, and the black-brown of negroes. Until modern times these race-tints have generally been described with too little care. Now, however, the traveler, by using Broca's set of pattern-colors, records the color of any tribe he is observing, with the accuracy of a mercer matching a piece of silk. The evaporation from the human skin is accompanied by a smell which differs in different races. This peculiarity, which not only indicates difference in the secretions of the skin, but seems connected with liability to certain fevers, etc., is a race-character of some importance.

The part of the human body which shows the greatest variety of color in different individuals is the iris of the eye. This is the more noticeable because the adjacent parts vary particularly little among mankind. Professor Broca, in his scale of colors of eyes, arranges shades of orange, green, blue, and violet-gray. But one has only to look closely into any eye to see the impossibility of recording its complex pattern of colors; indeed, what is done is to observe it from a distance, so that its tints blend into one uniform hue. It need hardly be said that what are popularly called black eyes are far from having the iris really black like the pupil; eyes described as black are commonly of the deepest shades of brown or violet. These so-called black eyes are by far the most numerous in the world, belonging not only to brown-black, brown, and yellow races, but even prevailing among the darker varieties of the white race, such as Greeks and Spaniards. In races with the darker skin and black hair, the darkest eyes generally prevail, while a fair complexion is usually accompanied by the lighter tints of iris, especially blue.

From ancient times, the color and form of the hair have been noticed as distinctive marks of race. Thus Strabo mentions the Ethiopians as black men with woolly hair, and Tacitus describes the German warriors of his day with their fierce blue eyes and tawny hair. As to color of hair, the most usual is black, or shades so dark as to be taken for black, which belongs not only to the dark-skinned Africans and Americans, but to the yellow Chinese and the dark whites, such as Hindoos or Jews. In the fair-white peoples of Northern Europe, on the contrary, flaxen or chestnut hair prevails. Thus we see that there is a connection between fair hair and fair skin, and dark hair and dark skin. But it is impossible to lay down a rule for intermediate tints, for the red-brown or auburn hair common in fair-skinned peoples occurs among darker races, and dark-brown hair has a still wider range. Our own extremely mixed nation shows every

variety, from flaxen and golden to raven black. As to the form of the hair, its well-known differences may be seen in the female portraits in Fig. 5, where the Africans on the left show the woolly or frizzy kind, where the hair naturally curls into little corkscrew spirals, while the Asiatic and American heads on the right have straight hair like a horse's mane. Between these extreme kinds are the flowing or wavy hair, and the curly hair which winds in large spirals; the English hair in the figure is rather of the latter variety. If cross-sections of single hairs are examined under the microscope, their differences of form are seen as in four of the sections by Pruner-Bey (Fig. 7). The almost circular Mongolian hair (a) hangs straight; the more curly European hair (b) has an oval or elliptical section; the woolly African hair (c) is more flattened; while the frizzy Papuan hair (d) is a yet more extreme example of the flattened ribbon-like kind. Not only the color and form of the hair, but its quantity, vary in different races.

That certain races are constitutionally fit, and others unfit, for certain climates, is a fact which the English have but too good reason to know. It is well known that races are not affected alike by certain diseases. While in equatorial Africa or the West Indies, the coast fever and yellow fever are so fatal or injurious to the new-come Europeans, the negroes, and even mulattoes, are almost untouched by this scourge of the white nations. On the other hand, we English look upon measles as a trifling complaint, and hear with astonishment of its being carried into Feejee, and there, aggravated, no doubt, by improper treatment, sweeping away the natives by thousands. It is plain that nations moving into a new climate, if they are to flourish, must become adapted in body to the new state of life. Fitness for a special climate, being matter of life or death to a race, must be reckoned among the chief of race-characters.

Travelers notice striking distinctions in the temper of races. There seems no difference of condition between the native Indian and the African negro in Brazil to make the brown man dull and sullen, while the black is overflowing with eagerness and gayety. So, in Europe, the unlikeness between the melancholy Russian peasant and the vivacious Italian can hardly depend altogether on climate and food and government. There seem to be in mankind inbred temperament and inbred capacity of mind. History points the great lesson that some races have marched on in civilization while others have stood still or fallen back, and we should partly look for an explanation of this in

differences of intellectual and moral powers between such tribes as the native Americans and Africans, and the old-world nations who overmatch and subdue them. In measuring the minds of the lower races, a good test is, how far their children are able to take a civilized education. The account generally given by European teachers who have had the children of lower races in their schools is that, though these often learn as well as the white children up to about twelve years old, they then fall off, and are left behind by the children of the ruling race.

It will be well now to examine more closely what a race is. Single portraits of men and women can only in a general way represent the nation they belong to, for no two of its individuals are really alike, not even brothers. What is looked for in such a race-portrait is the general

Fig. 9.—Caribs.

character belonging to the whole race. It is an often-repeated observation of travelers that a European landing among some people unlike his own, such as Chinese, or Mexican Indians, at first thinks them all alike. After days of careful observation he makes out their individual peculiarities, but at first his attention is occupied with the broad typical characters of the foreign race. It is just this broad type that the anthropologist desires to sketch and describe, and he selects as his examples such portraits of men and women as show it best. It is even possible to measure the type of a people. To give an idea of the working of this problem, let us suppose ourselves to be examining Scotchmen, and the first point to be settled how tall they are. Obviously there are some few as short as Lapps, and some as tall as Patagonians; these very short and tall men belong to the race, and yet are not its ordinary members. If, however, the whole population were measured and made to stand in order of height, there would be a crowd of men about five feet eight inches, but much fewer of either five feet four inches or six feet, and so on till the numbers decreased on either side to one or two giants, and one or two dwarfs. This is seen in Quetelet's diagram. Fig. 8, where the heights or ordinates of the binomial curve show the numbers of men of each stature, decreasing both ways from the central five feet eight inches, which is the stature of the mean or typical man. Here, in a total of near 2,600 men, there are 160 of five feet eight inches, but only about 150 of five feet seven inches or five feet nine inches, and so on, till not even ten men are found so short as five feet, or so tall as six feet four inches.

It thus appears that a race is a body of people comprising a regular set of variations, which center round one representative type. In the same way a race or nation is estimated as to other characters.

The people whom it is easiest to represent by single portraits are uncivilized tribes, in whose food and way of life there is little to cause difference between one man and another, and who have lived together and intermarried for many generations. Thus Fig. 9, taken from a photograph of a party of Caribs, is remarkable for the close likeness running through all. In such a nation the race-type is peculiarly easy to make out. It is by no means always thus easy to represent a whole population. To see how difficult it may be, one has only to look at an English crowd, with its endless diversity. But, to get a view of the problem of human varieties, it is best to attend to the simplest cases first, looking at some uniform and well-marked race, and asking what in the course of ages may happen to it.

The first thing to be noticed is its power of lasting. Where a people lives on in its own district, without too much change in habits, or mixture with other nations, there seems no reason to expect its type to alter. The Egyptian monuments show good instances of this permanence. Indeed, the ancient Egyptian race, who built the Pyramids, and whose life and toil are pictured on the walls of the tombs, are with little change still represented by the fellahs of the villages, who carry on the old labor under new tax-gatherers. Thus, too, the Ethiopians on the early Egyptian bass-reliefs may have their counterparts picked out still among the White Nile tribes, while we recognize in the figures of Phœnician or Israelite captives the familiar Jewish profile of our own day. Thus there is proof that a race may keep its special characters plainly recognizable for over thirty centuries, or a hundred generations. And this permanence of type may more or less remain when the race migrates far from its early home, as when African negroes

Fig. 11.—Cafusa Woman.

are carried into America, or Israelites naturalize themselves from Archangel to Singapore. Where marked change has taken place in the appearance of a nation, the cause of this change must be sought in intermarriage with foreigners, or altered conditions of life, or both. The result of intermarriage or crossing of races is familiar to all English people in one of its most conspicuous examples, the cross between white and negro called mulatto. The mulatto complexion and

Fig. 12.—Aheta (Negrito), Philippine Islands.

hair are intermediate between those of the parents, and new intermediate grades of complexion appear in the children of white and

Fig. 13.—Melanesians.

mulatto, called quadroon or quarter-blood, and so on; on the other hand, the descendants of negro and mulatto, called sambo, return toward the full negro type. This intermediate character is the general nature of crossed races, but with more or less tendency to revert to one or other of the parent types. To illustrate this. Fig. 10 gives the portrait of a Malay mother and her half-caste daughters, the father being a Spaniard; here, while all the children show their mixed race, it is sometimes the European and sometimes the Malay cast of features that prevails. The effect of mixture is also traceable in the hair, as may often be well noticed in a mulatto's crimped, curly locks, between the straighter European and the woolly African kind. The Cafusas of Brazil, a peculiar cross between the native tribes of the land and the imported negro slaves, are remarkable for their hair, which rises in a curly mass, forming a natural periwig which obliges the wearers to stoop low in passing through their hut-doors. This is seen in the portrait of a Cafusa (Fig. 11), and seems easily accounted for by the long stiff hair of the native American having acquired in some degree the negro frizziness.

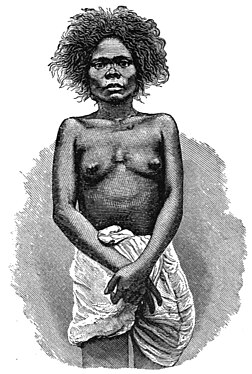

| Fig. 14.—South Australian (Man). | Fig. 15.—South Australian (Woman). |

Within the last few centuries it is well known that a large fraction of the world's population has actually come into existence by race-crossing. This is nowhere so evident as on the American Continent, where since the Spanish conquest such districts as Mexico are largely peopled by the mestizo descendants of Spaniards and native Americans, while the importation of African slaves in the West Indies has given rise to a mulatto population. By taking into account such inter-crossing of races, anthropologists have a reason to give for the endless shades of diversity among mankind, without attempting the hopeless task of classifying every little uncertain group of men into a special race. Among the natives of India, a variety of complexion and feature is found which can not be classified exactly by race. But it must be remembered that several very distinct varieties of men have contributed to the population of the country. So in Europe, taking the fair nations of the Baltic and the dark nations of the Mediterranean as two distinct races or varieties, their intercrossing may explain the infinite diversity of brown hair and intermediate complexion to be met with. If, then, it may be considered that man was already divided into a few great main races in remote antiquity, then intermarriage

Fig. 16.—Dravidian Hill-man (after Fryer).

through ages since will go far to account for the innumerable slighter varieties which shade into one another.

It is not enough to look at a race of men as a mere body of people happening to have a common type or likeness. For the reason of their likeness is plain, and indeed our calling them a race means that we consider them a breed whose common nature is inherited from common ancestors. Now, experience of the animal world shows that a race or breed, while capable of carrying on its likeness from generation to generation, is also capable of varying. It must be admitted that our knowledge of the manner and causes of race-variation among mankind is still very imperfect. The great races, black, brown, yellow, white, had already settled into their well-known characters before written record began, so that their formation is hidden far back in the prehistoric period. Nor are alterations of such amount known to have taken place in any people within the range of history.

That there is a real connection between the color of races and the climate they belong to, seems most likely from the so-called black peoples. Ancient writers were satisfied to account for the color of the Ethiopians by saying that the sun had burned them black, and, though modern anthropologists would not settle the question in this off-hand way, yet the map of the world shows that this darkest race-type is principally found in a tropical climate. The main line of black races

Fig. 17.—Calmuck (after Goldsmid).

stretches along the hot and fertile regions of the equator, from Guinea in West Africa to that great island of the Eastern Archipelago, which has its name of New Guinea from its negro-like natives. The type of the African negro race perhaps shows itself most perfectly in the nations near the equator, as in Guinea, but it spreads far and wide over the continent, shading off by crossing with lighter-colored races on its borders, such as the Berbers in the north, and the Arabs on the east coast. As the race spreads southward into Congo and the Caffre regions, there is noticed a less full negro complexion and feature, looking as though migration from the central region into new climates had somewhat modified the type. There are found in the Malay Peninsula and the Philippines scanty forest-tribes apparently allied to the Andamaners and classed under the general term Negritos (i. e., "little blacks"), seeming to belong to a race once widely spread over this part of the world, whose remnants have been driven by stronger new-come races to find refuge in the mountains. Fig. 12 represents one of them, an Aheta from the island of Luzon. Lastly come the widespread and complicated varieties of the Eastern negro race in the region known as Melanesia, the "black islands," extending from New Guinea to Feejee. The group of various islanders (Fig. 13), belonging to Bishop

Fig. 18.—Coreans.

Patteson's mission, shows plainly the resemblance to the African negro, though with some marked points of difference, as in the brows being more strongly ridged, and the nose being more prominent, even aquiline—a striking contrast to the African. The great variety of color in Melanesia, from the full brown-black down to chocolate or nut-brown, shows that there has been much crossing with lighter populations. Finally, the Tasmanians were a distant outlying population belonging to the Eastern blacks.

In Australia, there appears a thin population of roaming savages, strongly distinct from the blacker races of New Guinea at the north, and Tasmania at the south. The Australians, with skin of dark chocolate-color, may be taken as a special type of the brown races of man. while their skull is narrow and prognathous like the negro's, it differs from it in special points, and has peculiarities which distinguish it very certainly from that of other races. In the portraits of Australians (Figs. 14, 15), there may be noticed the heavy brows and projecting jaws, the wide but not flat nose, the full lips, and the curly but not woolly black hair. On the continent of India, the Dravidian hill-tribes present the type of the old dwellers in South and Central India before the conquest by the Aryan Hindoos. Fig. 16 represents one of the ruder Dravidians, from the Travancore forests.

| Fig. 19. Finn (Man). | Fig. 20.—Finn (Woman). |

The Mongoloid type of man has its best marked representatives on the vast steppes of Northern Asia. Their skin is brownish-yellow, the hair of the head black, coarse, and long, but face-hair scanty. Their skull is characterized by breadth, projection of cheek-bones, and forward position of the outer edge of the orbits, which, as well as the slightness of brow-ridges, the slanting aperture of the eyes, and the snub-nose, are observable in Fig. 17, and in Fig. 5 (d). The Mongoloid race is immense in range and numbers. The great nations of South-east Asia show their connection with it in the familiar complexion and features of the Chinese and Japanese. Fig. 18 gives portraits from Corea. In his wide migrations over the world, the Mongoloid, through change of climate and life, and still further by intermarriage with other races, loses more and more of his special points. It is so in the southeast, where in China and Japan the characteristic breadth of skull is lessened. In Europe, where from remotest antiquity hordes of Tartar race have poured in, their descendants have often preserved in their languages, such as Hungarian and Finnish, clearer traces of their Asiatic home than can be made out in their present types of complexion

Fig. 21.—Dyaks.

and feature. Yet the Finns (Figs. 19 and 20) have not lost the race-differences which mark them off from the Swedes among whom they dwell, and the stunted Lapps show some points of likeness to their Siberian kinsfolk.

On the Malay Peninsula, at the extreme southeast corner of Asia, appear the first members of the Malay race, seemingly a distant branch of the Mongoloid, which spreads over Sumatra, Java, and other islands of the Eastern Archipelago. Fig. 21 shows the Dyaks of Borneo, who represent the race in its wilder and perhaps less mixed state. The Micronesians and Polynesians show connection with the Malays in language, and more or less in bodily make. But they are not Malays proper, and there are seen among them high faces, narrow noses, and small mouths, which remind us of the European face. The Maoris

Fig. 22.—Colorado Indian (North America).

are still further from being pure Malays, as is seen by their more curly hair, often prominent and even aquiline noses.

Turning now to the double continent of America, we find in this New World a problem of race remarkably different from that of the Old World. The traveler who should cross the earth from Nova Zembla to the Cape of Good Hope or Van Diemen's Land would find in its various climates various strongly-marked kinds of men, white, yellow, brown, and black. But, if Columbus had surveyed America from the Arctic to the Antarctic regions, he would have found no such extreme unlikeness in the inhabitants. Apart from the Europeans and Africans who have poured in since the fifteenth century, the native Americans in general might be, as has often been said, of one race. Not that they are all alike, but their differences in stature, form of skull, feature, and complexion, though considerable, seem variations of a secondary kind. The race to which most anthropologists refer the native Americans is the Mongoloid of Eastern Asia, who are capable of accommodating themselves to the extremest climates, and who by the form of skull, the light-brown skin, straight black hair, and black eyes, show considerable agreement with the American tribes. Fig.

Fig. 23.—Swedes.

22 represents the wild hunting-tribes of North America in one of the finest forms now existing, the Colorado Indians.

Though commonly spoken of as one variety of mankind, it is plain that the white men are not a single uniform race, but a varied and mixed population. It is a step toward classing them to separate them into two great divisions, the dark-whites and fair-whites (melanochroi, xanthochroi). Ancient portraits have come down to us of the dark-white nations, as Assyrians, Phœnicians, Persians, Greeks, Romans; and when beside these are placed moderns such as the Andalusians, and the dark Welshmen or Bretons, and people from the Caucasus, it will be evident that the resemblance running-through all these can only be in broad and general characters. They have a dusky or brownish-white skin, black or deep-brown eyes, black hair, mostly wavy or curly; their skulls vary much in proportions, though seldom extremely broad or narrow, while the profile is upright, the nose straight or aquiline, the lips less full than in other races. Fig. 23, a group of Swedes, represents the fair-whites, whose transparent skin, flaxen hair, and blue eyes may be seen as well, though not as often, in England as in Scandinavia or North Germany. The intermarriage of the dark and fair varieties, which has gone on since early times, has resulted in numberless varieties of brown-haired people, between fair and dark in complexion. But as to the origin and first home of the fair and dark races

Fig. 24.—Gypsy.

themselves, it is hard to form an opinion. Language does much toward tracing the early history of the white nations, but it does not clear up the difficulty of separating fair-whites from dark-whites. Both sorts have been living united by national language, as at this day German is spoken by the fair Hanoverian and the darker Austrian. Among Keltic people, the Scotch Highlanders often remind us of the tall, red-haired Gauls described in classical history, but there are also passages which prove that smaller darker Kelts like the modern Welsh and Bretons existed then as well. A mixture of the white and brown races seems to have largely formed the population of countries where they meet. The Moors of North Africa, and many so-called Arabs who are darker than white men, may be thus accounted for. It is thus that in India millions who speak Hindoo languages show by their tint that their race is mixed between that of the Aryan conquerors of the land and its darker indigenes. An instructive instance of this very combination is to be seen in the gypsies, low-caste wanderers who found their way from India and spread over Europe not many centuries since. Fig. 24, a gypsy woman from Wallachia, is a favorable type of these latest incomers from the East, whose broken-down Hindoo dialect shows that part of their ancestry comes from our Aryan forefathers, while their complexion, swarthiest in the population of our country, marks also descent belonging to a darker zone of the human species.

Thus to map out the nations of the world among a few main varieties of man, and their combinations, is, in spite of its difficulty and uncertainty, a profitable task. But to account for the origin of these great primary varieties or races themselves, and exactly to assign to them their earliest homes, can not be usefully attempted in the present scantiness of evidence.

- ↑ Abridged from Chapter III of "Anthropology: An Introduction to the Study of Man and Civilization." By Edward B. Tylor, D.C.L., F.R.S. New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1881.