Popular Science Monthly/Volume 30/April 1887/On Melody in Speech

| ON MELODY IN SPEECH. |

By F. WEBER.

THERE is an infinite variety of interesting and pleasing sounds in Nature's music around us, that may be noted by an attentive ear; these sounds are mostly melodious and harmonious, or in some harmonious connection, and form exact intervals and chords.

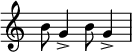

The wind in passing over houses, over trees, in gardens, fields, and forests, produces beautiful sounds of every variety, swelling from the softest to the loudest in majestic grandeur. On a stormy morning in town I heard the wind sing this melody over the roof of the house:

and on a similar night at Boulogne I copied the following passage that was wailing through the house in beautiful crescendo and decrescendo, and in many repetitions:

Thunder strikes us with awe by its deep, rolling tones; a storm or gale[1] on land or on the ocean sends forth fierce and sublime sounds, rushing from the lowest to the highest pitch; the stately flow of a great river sings an everlasting deep organ-point, while the lively brook sings melodiously, and modulates like human speech.

The suspended wires of an electric telegraph, when vibrated by a strong wind, produce touching and wailing sounds and chords over a whole country, like so many Æolian harps of sweet and sad sounds that may, from solemn strains and most perfect ideal harmonies, rise in an indescribable and inimitable crescendo, higher and higher, to moans and discords, and with the abating wind return to harmony.

All the animals on land, quadrupeds and bipeds, have their characteristic voices and calls in distinct intervals. Of our domestic animals the cow gives a perfect fifth and octave or tenth:

The dog barks in a fifth or fourth:

The donkey in coarse voice brays in a perfect octave:

The horse neighs in a descent on the chromatic scale:

The cat in a meek mood cries:

and at night on the roof in the garden may howl over an extended compass, and at times give cries like those of an infant.

The hens, geese and ducks in a farmyard chatter in pleasing chorus, and proud chanticleer crows piercing solos between, in the diminished triad and seventh chord:

The birds in bushes and trees, in gardens and woods, sing most beautiful tones in exact intervals, even in melodious chords and in measured time. In passing a garden in the southwest of London on a summer's afternoon, I noted the following tones of different birds in a few minutes:

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \time 2/4 \relative g' { \autoBeamOff g8 g d'4 \bar "||"

\time 3/4 r8 a b4 b | r8 a b4 b \bar "||"

\time 2/4 f'8[( e]) f[( e]) \bar "||"

a,[( b]) a[( b]) \bar "||" \break

\time 4/4 e,2( b'4) r | e,2( b'4) r \bar "||"

\autoBeamOn \time 6/8 d,8( g) g d( g) g \bar "||"

\time 2/4 f'[ f e e] \bar "||"

\time 6/8 a,( f') e a,( f') e \bar "||"

\time 3/8 a, fis' d \bar "||" \break

\time 4/4 g, g d' d g, g d' d \bar "||"

\time 3/4 a( e') e e dis4 \bar "||"

\time 2/4 a16( b) a8 a16( b) a8 \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/g/2gqf22vqz97tb7deqkzj9klf4fbvahf/2gqf22vq.png)

Animals of the same species vary in their musical gift, as they do in other points. Some animals are very fond of music and greatly affected by it, while others are insensible or quite averse to it; of the former the horse has already in remote antiquity been mentioned for its joy at the sound of the trumpet, as we read in the book of Job (xxxix, 25). Shakespeare also says in his "Merchant of Venice":

Or race of youthful and unhandled colts,

Fetching mad bounds, bellowing, and neighing loud,

Which is the hot condition of their blood;

If they but hear perchance a trumpet sound,

Or any air of music touch their ears.

You shall perceive them make a mutual stand,

Their savage eyes turned to a modest gaze,

A touching proof of this old truth was given in the late Franco-German War, when, in the evening after the battle of Gravelotte, on the trumpet-signal for the roll-call of the Life-Guards, more than three hundred riderless horses, some of them wounded and hobbling on three legs, answered the well-known sounds and mustered with the remnant of their regiment.

Of the nightingale it is said that in spring the males perch on a tree opposite the hens and sing their best one after another; where-upon the hens select their mates and fly off with them.

The intervals we observe most in the voices of animals are fifths, octaves, and thirds, and also fourths and sixths.

In inanimate sounding bodies, as in church-bells, in the larger strings of the piano, in the Æolian harp (or wind-harp), the fifth and tenth (or third in the next higher octave), commonly called harmonics, are very distinctly heard toward the end of the principal sound.

The human voice in speaking uses also these intervals foremost, but it moves also over most of the other intervals in melodious and harmonious combinations. We speak in melodies and harmonies, improvising them by the impulse of our thoughts and feelings over an extent or compass of one and a half to two octaves; as every plant grows with a certain color, so every sentence is spoken in some melody which rises in sympathy with the sense and sentiment of the words, giving character to the whole sentence; and from the quality and accent of this musical investment, the truth and sincerity of the words may be felt, and the character of the speaker be traced.

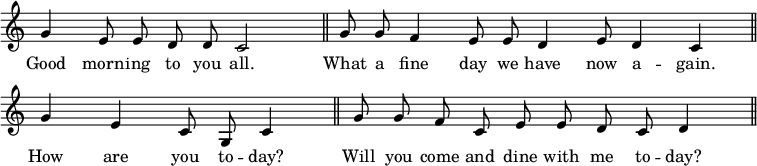

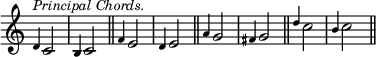

Sentences are spoken in a certain musical key, and are mostly begun on the fifth or dominant of the scale of the key-note, from which they descend in seconds or thirds or other intervals to the key-note, and, may be, down to the lower dominant:

Or they begin on the key-note and move to the dominant:

Or they ascend from the dominant to the octave, and to the ninth and tenth:

Many expressions are begun on the sixth as on a leading tone to the dominant:

The voice moves mostly up and down in the principal scale and chord, and in their relative harmonies, and frequently dwells on introducing tones from above or below to a tone of any of these chords:

Common conversation is generally held in the major mode, and in the same key:

But when sad and pathetic it is in minor:

An unfriendly reply is mostly in an unrelated key:

Every person has his own fundamental and favorite key in which he generally speaks, but which he often transposes higher or lower in sympathy to other voices, and when he is excited. In divine service at church I have heard the minister begin in his natural key, and the choir sing the response in a higher key; when the minister, possessing a musical ear, gradually rose to the tone of the choir. In one instance the minister began the communion service in E flat, and the choir and organ gave the response in F. The minister gradually raised his voice, and by the fourth commandment met the tone of the choir, wherein he continued to the end.

In ordinary conversation the different voices speak in the key of B flat, B, or C, persons with soprano or tenor voices moving in the upper part of the scale, and the alto and bass voices holding to the lower part of the same, and the replies turning often to the dominant or subdominant:

Conversation in a railway-train, of father, mother, and two daughters:

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \relative e' { \cadenzaOn e4^\markup { \smaller \italic "I. Daughter." } c e c g' e \bar "|" e^\markup { \smaller \italic Mother. } c c \bar "|" \clef bass e^\markup { \smaller \italic Father. } c g \bar "|" \clef treble a'^\markup { \smaller \italic "II. D." } g c, \bar "|" g^\markup { \smaller \italic M. } b c c c a g \bar "|"

a'^\markup { \smaller \italic "II. D." } g f \bar "|" d4.^\markup { \smaller \italic M. } c8 b4 g g \bar "|" c^\markup { \smaller \italic "I. D." } c8[ c] e4 c \bar "|" e^\markup { \smaller \italic M. } e d \bar "|" c^\markup { \smaller \italic "I. D." } \bar "|" g^\markup { \smaller \italic M. } \bar "|" d'^\markup { \smaller \italic "I. D." } e f e e c \bar "|"

f^\markup { \smaller \italic M. } e c \bar "|" \clef bass a^\markup { \smaller \italic F. } f g e c' \bar "|" \clef treble a'^\markup { \smaller \italic "I. D." } g c, e \bar "|" f^\markup { \smaller \italic "II. D." } e e c'2 \bar "|" g4^\markup { \smaller \italic "I. D." } f e \bar "|" g^\markup { \smaller \italic M. } e \bar "|"

f^\markup { \smaller \italic "II. D." } e c e g c \bar "|" f,^\markup { \smaller \italic M. } e \bar "|" c'^\markup { \smaller \italic "II. D." } a g f e \bar "|" f^\markup { \smaller \italic M. } e \bar "|" \clef bass a,^\markup { \smaller \italic F. } g f e a g \bar "|" \clef treble a'^\markup { \smaller \italic "II. D." } g \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/4/c/4cyy8xwrdrnx2r66m62b14lvrws73qv/4cyy8xwr.png)

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \key bes \major \relative b' { \cadenzaOn bes4^\markup { \smaller \italic Boy. } bes8 bes d4 bes \bar "|" d,^\markup { \smaller \italic Mother. } f( bes,) \bar "|" bes'^\markup { \smaller \italic Boy. } bes8[ bes] d4 bes \bar "|" g^\markup { \smaller \italic Mother. } bes8[( ees,]) \bar "|" g4 ees \bar "||" d f \bar "||" g^\markup { \smaller \italic "Other Woman." } bes( g) \bar "||" d^\markup { \smaller \italic Mother. } f \bar "||" }

\addlyrics { _ _ _ _ _ No, no. _ _ _ _ No, no, come on. Good -- bye. Good -- bye. Good -- bye. } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/i/x/ixcg3ihfl0j3keo8xgpfwssurkrkhr3/ixcg3ihf.png)

In a recent journey from Calais to Boulogne, Amiens, and Rheims, I found most people there speak in the key of B flat major and minor. The large bells at the belfry at Boulogne and at the cathedral at Rheims also have the low B flat, and may have been cast in that tone to be in unison with the voice of the people. Some of the convesations along the route, and the calling out of the names of railway-stations, were as follow:

Two women on Boulogne pier.

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \key des \major \clef bass \relative b, { \cadenzaOn bes8^\markup { \smaller \italic I. } des f ges4 f \bar "|" f8[^\markup { \smaller \italic II. } bes c] des[ ees des] f,4 \bar "|" f,8^\markup { \smaller \italic I. } f f f bes4 \bar "|" des8[^\markup { \smaller \italic II. } des des des] f[ des f bes] des4 \bar "|" des,8[^\markup { \smaller \italic I. } f bes] des,4 f \bar "|" f8^\markup { \smaller \italic II. } f des'4 \bar "|" bes^\markup { \smaller \italic I. } des, f f bes, des \bar "||" }

\addlyrics { _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ mais je ne crois pas. _ _ _ _ _ _ point du tout. } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/t/a/ta5d6vmz4gq0xigfy0ed0y7hzb4pe21/ta5d6vmz.png)

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \key bes \major \clef bass \cadenzaOn bes,4. bes,8 bes,4 g f4. f8 f4 bes bes, \bar "||" f8[ bes,] f[ bes,] bes4 \bar "|" bes, bes g f ees d c d c bes \bar "|" ees ees f g bes g f2 \bar "|" g4 bes f g bes \bar "|" f g f d bes \bar "||" }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/9/v/9vof00t19o0li191i2gx7qazltj9cd1/9vof00t1.png)

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \key bes \major \relative f' { \cadenzaOn f8^\markup { \smaller \italic Child. } f g4 bes \bar "|" f8[^\markup { \smaller \italic Mother. } d ees d c] bes4 bes f' d f d f g d2 \bar "|" a'4^\markup { \smaller \italic Child. } bes c bes \bar "|" d,^\markup { \smaller \italic Mother. } bes8[ bes] d4 f \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/7/6/7668a8raa0jeqtt0ilyuc0d8d82q1d2/7668a8ra.png)

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \key bes \major \clef bass \cadenzaOn { f8^\markup { \smaller \italic "I. Man." } f f d f f f a4 \bar "|" d^\markup { \smaller \italic II. } bes2 \bar "|" d8[^\markup { \smaller \italic I. } f d] d[ f d] d[ f d] bes4 \bar "|" bes,^\markup { \smaller \italic II. } bes f2 \bar "||" }

\addlyrics { Y a -- t'il en -- core de la place? mais oui _ _ _ _ au re -- voir. } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/o/h/ohs3mh3nxpg6v1a6wrbuivwelpefmuj/ohs3mh3n.png)

At the fish-market at Boulogne:

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \key bes \major \clef bass \cadenzaOn { bes[^\markup { \smaller \italic I. } bes bes f] \bar "|" bes[^\markup { \smaller \italic II. } bes bes] c'[ f f] \bar "|" bes8[^\markup { \smaller \italic III. } bes bes] bes[ bes bes] bes[ bes bes] ees4 \bar "||" \break

bes, d f bes \bar "|" d f bes, bes \bar "|" bes d f bes, \bar "|" f8[ ees ees ees] g4 c' \bar "|" g g bes d \bar "|" f8[ g f d] f[ f] c'4 \bar "|" f8[ g f d] f[ f] bes4 \bar "|" c ees d bes, \bar "|" d f c' bes \bar "||" d8^"At Calais." d d d d f4 \bar "|" bes,2 \bar "||" }

\addlyrics { _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ le ba -- teau est il prêt? oui. } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/o/6/o6zkszheqcn85qzh2mwr7pbe1mtfgcs/o6zkszhe.png)

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \key bes \major \clef bass \relative b { \cadenzaOn bes8 f f4 \bar "|" f8 bes a2 \bar "||" f4 bes des8[ ees8] des4 \bar "|" f, bes f'8[ f] f4 \bar "||" a, c2 \bar "|" ees4 a,2 \bar "||" f8 f f bes4 bes \bar "||" f' d2 \bar "||" d,8 g bes4 g \bar "||" bes8 bes g c8[ ees] d4 \bar "||" bes, f'2 \bar "||" f8 bes a2 \bar "||" g4 f2 \bar "||" f'4 d2 \bar "||" d,8 ees f2 \bar "||" bes,8 d f4 \bar "||" bes,8 bes bes d f4 \bar "||" c'4 a2 \bar "||" d,8 d g f4 \bar "||" d g( f) \bar "||" d f( ees) \bar "||" d f2 \bar "||" }

\addlyrics { Neuf -- châ -- tel, Neuf châ -- tel. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Ver -- ton, Ver -- ton, Cou -- chelle le tem -- ple. Ver -- ton. Ab -- be -- vil -- le. Mon -- tez en voi -- ture. St. Erme. Var -- sig -- ny. La Fère. Ter -- gnier. A -- mi -- ens. Mar -- tel -- lan. Vil -- liers Bre -- ton -- neux. St. Josse. Dan -- nes Ca -- miers. Rix -- ant, Rix -- ant, Rix -- ant. } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/i/y/iy9yjinn3wajk99p1wu8g0ju5wb452d/iy9yjinn.png)

The French railway guards and conductors deserve to be complimented for their melodious calls of the names of the stations.

The omnibus conductors in London ordinarily call out in the key of B flat; but at busy places and hours they speak in a higher key. At Charing Cross I heard them call:

The paper boys call:

Some of the cries of venders in the streets are quite beautiful and touching, like the following I heard and noted down of a boy in Long Acre:

Of a man at Boulogne:

A collection of such melodious and pleasant cries from towns in England and abroad would be most interesting in showing the musical talent and taste of the people who invent and use them.

Friendly conversations keep mostly to the key of the principal person of the circle, who at the time gives, not only the moral and social tone, but also the musical tone to all around him; and if any one of the company would speak in a different tone, he would be out of tune and out of countenance with the others. When we read by ourselves we speak in C, or in B flat, or lower still; but when we read to others, we raise our voice to the fourth or fifth of our own key, that is, to G, or F, or E flat.

We ought to study and exercise our voice in the different keys in which we may have to speak, through the whole extent of our voice, to enrich it with an easy flow of a variety of tones, so as to match our words and sentences with suitable melodious turns, to render them fervid and impressive, to touch a vibrating chord of sympathy and interest in our hearers.

When abroad I heard once a young orator speaking for nearly half an hour, wnth every sentence descending in these off tones of the scaleIn a speech of some length the orator will save his voice by keeping more in the middle part of it, on and about his individual dominant, which part requires least strain and is the most pleasing; from where he may with good effect rise or descend in accordance with the exciting or soothing flow of his ideas and sentiments. By thus arranging the melodious part of his speech somewhat like a musical composition, and suitably contrasting the high parts of his voice with the middle and lower parts, he will engage and rivet his audience all the more to every word.

Some persons spoil the sonorousness of their voice by not letting it flow out freely and naturally, by giving it a peculiar throaty twang, by speaking too high, or by using the head voice (falsetto) too much. The natural voice, free from the chest, is most agreeable and effective in conversation and in addressing an audience; it is least fatiguing to the speaker and to the hearer, and penetrates farthest.

Spirited and impressive sermons, mostly in a major key, modulate in elevating ideas to the dominant, in soothing sentiments to the sub-dominant and the relative minor keys, but return and end in the principal key like a musical composition.

Collections of melodies in sermons and speeches of different nations would be most interesting and useful to students in oratory, be it for a dignified and becoming rendering of the great truths and sentiments in religion and humanity, or for persuasion, admonition, and encouragement in secular matters.

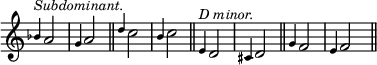

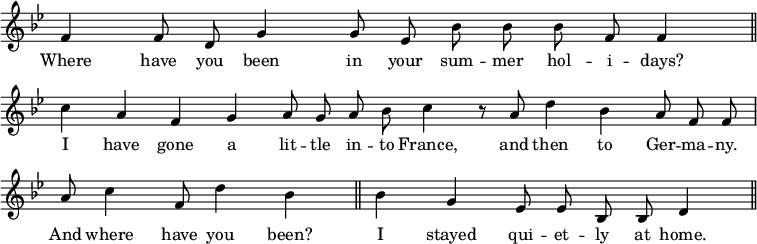

The following melodies I have copied from a speech by an Oxford professor, and from a sermon by an English bishop.

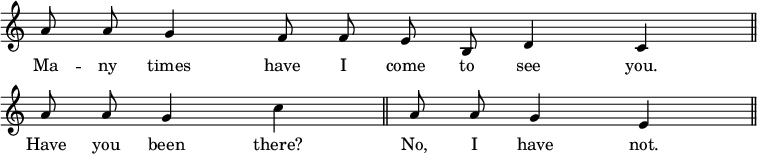

From an English speech (by an Oxford professor):

From (the sermon of an English bishop) an English sermon:

—Longman's Magazine.

- ↑ A gale in old Saxon and English means also a song, and with the bold sea-kings of old may also have had this meaning—a song on the ocean. Gale in Danish means to "crow": Hanen galer, the cock crows. Other relatives, the English to call and the German Kehle, throat, the organ of song.