Popular Science Monthly/Volume 39/October 1891/Dress and Adornment II

| DRESS AND ADORNMENT. |

II. DRESS.

By Prof. FREDERICK STARR.

WHY has dress been developed? We answer at once, to serve as a covering to the body. But, if we think over the matter a moment, we shall see that three different motives may have operated:

1. The desire for ornament.

2. The wish to protect one's self against weather and harm.

3. The feeling of shame.

Dress may, then, be a decoration, a protection, a covering. All three of these motives have no doubt acted, but we believe the first has been the earliest and most powerful.

Were modesty and the feeling of shame the only factors in urging on dress development we should expect to find no naked races; there should be an inflexible rule as to what constitutes modesty, and covering should always be more important than display. In reality we find the opposite of all these. "What is necessary is always less important than luxury." Ornament is never lacking clothing often is. Peschel has somewhat fully discussed this matter of nakedness and shame. He tells us that there are tribes who, when first discovered, lived naked. Among those he names are Australians, Andamanese, some White Nile tribes, the red Soudanese, Bushmen, Guanches, some Guianians, Coronados, and the Botocudos. All these people, dwelling in a state of nudity, seemed to have no idea of shame on that account. The feeling of shame for nudity is not then universal, nor have we any reason to believe that it ever was.

It is true that all these tribes are dark-skinned people, and it is claimed by some writers that a dark skin lessens the realization of nakedness. Adolph Bastian said that his "skin appeared abnormal and by no means beautiful by contrast" with that of the dark peoples he met. Jagor said of a King from Coromandel who wore only a turban and a waistcoat, "He did not look indecent, for his dark color almost removed the impression of nudity." At Yuma, Arizona, the Yuma Apaches flock to the passenger trains and are looked at with great interest by the tourists. We have been profoundly impressed with the absolute insensibility of these ladies and gentlemen to the fact that the Indians are really almost naked. That a dark skin does lessen the feeling that a man looked at by a white observer is naked is certain. That it lessens in any degree the dark man's own perception of the fact is doubtful.

In developing the subject still further, Peschel states that there is no fixed standard for shame on account of bodily exposure. Of what one is ashamed varies with race, with style of dress, and with fashion. "The Mussulman of Ferghana would be shocked by bare shoulders at a ball; an Arab woman does not expose the hair on the back of her head, nor the Chinese woman her bandaged foot." An early traveler describes an Australian woman who wore bands of shells about her head and arms and a cord of human hair about her waist. Without this cord she felt shame; yet it was not in the least a protection or covering. Humboldt, in speaking of skin-painting among some South Americans, says, "Shame was felt by the Indian if he were seen unpainted." In these two interesting cases we strike the key-note of the whole subject—"it is the absence of the customary that causes shame." To use a homely and not original illustration among ourselves, a man who forgets his necktie and goes to business without it, on discovering its absence feels a chagrin and uneasiness quite out of proportion to the importance of the matter. We see that shame for nudity is not universal, that the standard of decency in covering the body varies, and that the feeling of shame seems to arise from the absence of what is customary. It seems to us, from these facts, that the idea of clothing as a modest covering is relatively recent, and that it is subsequent to dress development.

Nor does it seem that protection has been the chief factor in dress development. The Fuegians went almost naked even in bad weather; "a small square of skin hung over one shoulder and was simply shifted to windward." On the other hand, clothing has been developed to a very elaborate extent in many regions where the climate does not at all compel its use.

The third of the three motives mentioned remains. Dress has generally developed out of ornament. That it has, after being developed, often been turned into a modest covering and a protection is unquestioned. No people are without ornaments; many are without dress. Ornaments are of two kinds—those directly fixed into the body, and those which are attached by a cord or band. As soon as man hung an ornament on such a band, dress evolution had begun. Lippert calls attention to the fact that some parts of the body are naturally fitted to support bands or girdles; they are the temples, neck, arms above elbow, wrists, waist, legs above knee.

Fig. 1.—African Aprons, wrapped for Storage.

ankles. There are girdles and bands of an ornamental character and in the greatest variety for all these parts. They will be described and illustrated in our next lecture. Nothing is more simple than the passage of a cord about some one of these places, and the hanging upon it of objects supposed to be beautiful. Two of these ornament-bearers would be capable of carrying a particularly heavy load of objects. These are the neck and the loins girdles. To what extent the hanging of ornament upon these girdles is carried is shown by the following cases mentioned by Wood. A young Kaffir dressed for a visit is described as follows: "He will wear furs, among them the Angora goat; feathers in his head-dress; globular tufts of beautiful feathers on his forehead or on the back of his head; eagle feathers in fine head-dresses, as also ostrich, lory, and peacock feathers. He ties so many tufts and tails to his waist-girdle that he may almost be said to wear a kilt." Of some other Africans—"Around their waists they wear such masses of beads and other ornaments that a solid kind of cuirass is made of them and the center of the body quite covered with them." In these cases, which might easily be multiplied, is it not evident that the objects hung on to the girdle are simply ornamental, and

Fig. 2.—Southern Type of Dress. Loochoo Islanders. The hair-dressing is ethnically characteristic.

that one accustomed to wearing such a mass of objects would feel shame at their absence? This ornamental mass would, with introduction of newer and lighter materials, give way to an apron which would be really a modest covering, although originating in ornament. The African apron and the Polynesian liku are developed from the waist-cord with its ornaments. In the same way the neck-girdle might give rise to a cape for the shoulders.

Examining the dress of the world, we can distinguish two fairly marked types which we may designate, as Lippert does, the northern and southern types of dress. The latter is really a development from just these two pieces of dress—the neck-girdle and the loins-girdle. It has originated in and is adapted to warm climates, it is loose and flowing, it has evidently originated in ornament. It is the dress of China and Japan, of the Orient, of ancient Greece and Rome, and of old Egypt. No matter how elaborate the style or how beautiful the material, such dress may all be reduced to the two simple articles before mentioned. The northern type may have been largely due to the wish for protection against the cold, although even here the ornamental has not been lacking in influence. Perfectly developed, the type presents us close-fitting jackets and trousers with tight sleeves and legs. The first materials for this type of dress were skins, and the form of the garments is doubtless due to the fact that the skins were at first tied with thongs about the limbs and trunk. We have said that even here we find the influence of the strife for display. We believe skins were first worn as trophies. Frequently in the classics the heroes are described as wearing skins of lions or leopards. In Egypt, Diodorus says the king wore a lion's, dragon's, or bull's skin over his shoulder. In a severe climate such trophies would become protective coverings, The forms of southern dress were developed by draping, those of the northern by wrapping; but, as the body draped and wrapped was the same, we need not be surprised at finding somewhat similar garments in both series. Jackets  Fig. 3.—Northern Type of Dress. Eskimo. and trousers are worn by both Chinese and Eskimo, but in the one they are loose-fitting, flowing garments, in the other close-fitting and tight.

Fig. 3.—Northern Type of Dress. Eskimo. and trousers are worn by both Chinese and Eskimo, but in the one they are loose-fitting, flowing garments, in the other close-fitting and tight.

It is most interesting to see how, after the idea of dress was once developed, it has stimulated man's mental progress and mechanical skill in searching for better materials for clothing and devising means of using them. Let us briefly consider some of these dress materials and the ways in which they are treated to render them fit for use. Skins were employed early and are in use the world over. Schweinfurth, in speaking of his Niam-niam guides, says: "They wear large aprons, like cooper aprons, in the early morning, as a protection against dews and dampness. None of these skins are more beautiful than that of the bushbok, with its rows of white spots and stripes upon a yellow ground. Leopard-skins are worn by chiefs only." Of the Bongo the same author says that they "simply knead and full by ashes and dung the skin for their aprons, etc.; they also apply fat and oil until the skins are pliant." Kaffirs, we are told, invite friends to help them in dressing skins. The party "sit around the skin and scrape it, carefully removing all fat and reducing the thickness. They

Fig. 4.—Beating-club, used in making Tappa Cloth; Sticks for stamping Patterns on Bark Cloth. Hawaiian Islands.

then work it all over by pulling and stretching it over their knees. When completely kneaded each takes a bunch of iron skewers or acacia thorns and revolves the bundle in his hands, points downward, on the skin, to tear up the fibers and add pliancy and raise a fine thick nap. Powder of decayed acacia stumps is then rubbed into the skin with the hands. A little grease is then carefully rubbed in." The beautiful buckskin which our own Indians make is well known. The skin is soaked in a lye of wood ashes for some time. It is then stretched and pegged out, the hair scraped off, and brains of deer rubbed in. Among the Eskimos we find some very handsome garments made of bird-skins. These, as other skins, are softened by being chewed between the teeth. These various cases interestingly show the beginnings of tanning.

Nature offers ready-made garments in leaves, and, where modesty is the motive to dress, we find them used. In New Caledonia men wear a single leaf hanging from a girdle, and in New Guinea a belt of leaves or rushes five inches wide and long behind. Kingsmill women wore a long rope of human hair two hundred to three hundred feet long, to which was hung a dress of leaves. Very interesting is the fact that at Madras, once a year, the whole low caste population put aside their ordinary garments and wear leaves. Later we shall refer to this instance again.

Nature is not always so kind as in Brazil, where, Tylor says, a man who wishes a garment goes to a shirt tree. He cuts a four or five foot length of trunk or large branch, gets the bark off in an entire tube, which he has then to soak and beat soft and cut slits in for arm-holes. A short length makes a woman's waist. But bark is used as a dress material widely. Throughout a large portion of Oceania the natives have their tapa, masi, or gnatoo cloth, made by beating the bark of the malo tree. Wood quotes the process of manufacture of the gnatoo:

A circular incision is made around the trees near the roots with a shell, deep enough to penetrate the bark. The tree is then broken off. It is left in the sun for a couple of days to become partly dry, so that the inner and outer bark may be stripped off together without leaving any of it behind. The bark is then soaked in water for a day and a night, and scraped carefully with shells, to remove the outer bark, which is thrown away. It now swells and becomes tougher. Being thus far prepared, beating (tootoo) begins. This is done by a mallet a foot long and two inches thick, two sides horizontally grooved a line in depth, with intervals of a quarter of an inch. The bark, which is two to three feet long and one to three inches broad, is then laid on a beam of wood six inches long and nine inches broad and thick, which is separated from the ground about an inch by bits of wood, so it may vibrate. Placing the bark before her, the woman beats with her right hand, and moves the bark to and fro with her left, so as to beat it evenly, using the grooved side of the mallet first and then the smooth one. Women generally beat alternately and early in the morning. In about half an hour the material is beaten sufficiently thin, and has spread so much laterally as to be square when folded. They double it several times during the process, so as to spread it more equally and to prevent breaking. Thus prepared, it is called fetage. The second part of the operation is called cocanga, or printing with cocoa. The berries of the toe are gathered—the pulp of which makes a paste. The root of mahoe is sometimes used. The soft bark of the cocoanut is scraped off and yields a reddish-brown dye. A stampis made of dry leaves of the paoonga sewed together so as to be of sufficient size, and afterward embroidered with cocoanut-husk fiber. These stamps are generally two feet long by half a foot broad. They are tied into

Fig. 5.—Garment of Beaten Bark. South Sea Islands.

the convex side of cylinders of wood six or eight feet long, with the pattern side up. The bark cloth is laid on and smeared over with a piece of gnatoo dipped in dye. Another piece of the gnatoo is laid over the first, so as not to exactly match it. Both are pieced out in all directions, and three layers are built, each being stained separately. The process is continued until a piece six feet broad and forty or fifty yards in length has been printed. This is folded and baked under ground, to harden and darken the dye, also to deprive it of the smoky smell due to cocoa. When thus exposed for a few hours, the cloth is spread on grass or sand and the operation of toogihea begins—stamping it in certain places with the juice of hea, which constitutes a brilliant red varnish. This is done in straight lines, along the junctions of the printed edges, and serves to conceal irregularities. It is also done in other places in the form of round spots an inch and a quarter in diameter. Exposed to dew, and next day to the sun, it is packed for future use. When not printed or stained the cloth is called tapa.

Schweinfurth describes the urostigma of the Monbuttos, which  Fig. 6.—South Sea Islander with Dress of Bark Cloth. is used much as the shirt tree of the Brazilians. He says that nearly every house has its trees, which need cultivation. He states that the removal of the bark does no harm to the tree, and that a new growth is ready in three years. He adds the interesting fact that this bark cloth is the common dress, and that skins are worn only when in fancy dance dress. The significance of this we shall see later.

Fig. 6.—South Sea Islander with Dress of Bark Cloth. is used much as the shirt tree of the Brazilians. He says that nearly every house has its trees, which need cultivation. He states that the removal of the bark does no harm to the tree, and that a new growth is ready in three years. He adds the interesting fact that this bark cloth is the common dress, and that skins are worn only when in fancy dance dress. The significance of this we shall see later.

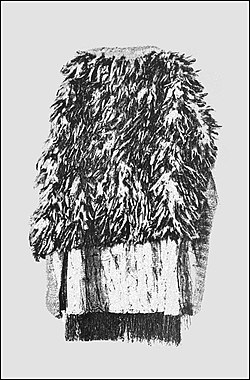

Besides tanning, beating bark, and felting hair, the search for dress materials and study of their use have given rise to the art of weaving. This art begins in basketry and plaiting, Seldom at present do we find plaited dress articles. Wood, however, mentions some of interest. In the lower Murray region of Australia a circular mat (paringkoont) made of reed ropes coiled and bound together by fibers of chewed bulmol is worn. It is simply folded about the body and tied at the waist. In New Zealand the native wild flax supplies a wonderfully fine material for plaiting. It is fully utilized, and nowhere do we find more elegant mat garments. Wood describes several kinds.

A mat may be made of phormium leaf cut into strips an inch wide, each alternate one being dyed black. Each strip is divided into eight little strips or thongs plaited into a checker-work. Other styles of "mats" are made of phormium. The fibers of the leaf of this plant are strong, fine, and silky. A weaving-frame on sticks a foot or so from the ground is used in making some of these mats. Upon it is a weft of strings close together and drawn tight; the weft is double, passed under and over each yarn. A bone beater is used. Even a common mat takes eighteen months in making. All mats are ornamented with strings or tags: thus, one was covered with long, cylindrical ornaments, looking like porcupine-quills, hard, alternately yellow and black. These are made of phormium-leaf epidermis rolled up. The kaitaka is a peculiarly beautiful mat, soft and fine, plain except the border, which is in some cases two feet deep, elaborately woven in Van-dyked patterns of black, red, and white. War cloaks of chiefs  Fig. 7.—Monbutto Warriors with Dress of Urostigma Bark.(Schweinfurth.) are woven in much the same way, but hair is woven in so that the mat looks like a skin. Such cost four years' labor, and no two are alike.

Fig. 7.—Monbutto Warriors with Dress of Urostigma Bark.(Schweinfurth.) are woven in much the same way, but hair is woven in so that the mat looks like a skin. Such cost four years' labor, and no two are alike.

Out of such plaiting as this true weaving grows. The only difference between plaiting and true weaving is that the splints or ribbons of the one are replaced by cords or threads. The development of the great looms of to-day has been often enough traced. A good example of their beginnings is the very simple little wooden cibohikan of our Sacs and Foxes.

Some of the articles of dress made by savage and barbarous peoples deserve notice. They are sometimes elegant in material and beautiful in workmanship. No furrier can do better work than does the Kaffir kaross-maker.

A large kaross is worn fur inward. If made of several skins, the heads are in a row along the upper margin. This is bent back and falls outward as a cape. Jackal-skin is prized as thick and soft, with rich black mottlings. That of the meerkat is also valued. One kaross of thirty-six skins' was sewed very neatly; each skin was pierced by a weapon; yet, viewed on the hairy side, not a hole is visible, circular pieces of skin being "let in." Great skill is shown in selecting these pieces, as the meerkat is extremely variable. A professional kaross-maker takes two pieces of fur, places them together, hairy sides in and edges just matching. He repeatedly passes the long needle between the two pieces, so as to press the hair downward and out of the way. He then bores a

Fig. 8.—Liku. South Sea Islands.

few holes in a line with each other and passes a sinew fiber through them, casting a single hitch over each hole but leaving the thread loose. Two or three such holes being made and the thread passed through, he draws it tight so as to produce a sort of lock-stitch, perfectly safe and neat. Finally, he rubs down the seams so that the edges lie as if one piece. The gray jackal is more prized than the black; though not so beautiful, it is more rare. One kaross, five feet three inches deep by three feet wide, was made of several skins. The skin is darkest along the back. The maker has here selected skins and uses the darker ones for center and lets it fade away toward the edges to give the effect of one large skin. Not only so, but by careful cutting and piecing the effect was carried out. All the heads are set in a row along the upper edge. The lower edge is made from the skin of the paws—very dark, in a stripe four inches wide. In some karosses, two feet from the top and on the outer edges, are small wings or projections, one foot long by eight inches wide. These wrap around the shoulders and arms. The kaross reaches the knees in front and a foot lower behind and at the sides. The edge of the kaross is bound on the inside with membrane band to add to its strength. This is made from antelope-skin, rolled up and buried in the ground until partly putrefied; it is then split. The needles used are like skewers and eyeless. The thread is of sinews—the best of which are from the neck of the giraffe. Naturally, these are stiff, angular, and elastic. When wanted for use it is steeped in hot water until quite soft, and then beaten between stones. This separates it into filaments of any fineness and very strong. The sinew is used wet and so is the leather; when dry, the seams are very tight and close (Wood).

The Kaffir also wears an apron called an isinene. This is simply a waist-girdle to which are hung trophies. Though these are supposed to be tails of the leopard, lion, or buffalo, they are seldom really such. One specimen was made up of fourteen tails of twisted monkey-skin, each about fourteen inches long, finely sewed to a belt of the same material covered with red and white beads. Across the belt. were two rows of brass buttons. Among the Polynesians the common dress is the liku, a fringed girdle of thongs of some vegetable material. These thongs may be of no greater coarseness than pack-thread, or they may be of some  Fig. 9.—South Sea Islander with Liku. width and neatly crimped. Feather garments are frequently of great beauty. The finest come from South America and the south seas. A Mundurucu apron consisted of a backing of cotton string into which were worked feathers: a band of jetty black at the lower end, above it bright yellow, and then scarlet with blue and yellow pattern in it; the upper edge was set with brilliant beetle elytra. The most famous feather mantles were those made for royal use in Hawaii, consisting of mesh-work into which were worked feathers of the yellow melithreptes. Only two of these feathers were produced at one time by one bird, and the mantles were valued at an almost fabulous price. Last of these descriptions we may quote what Schweinfurth says of the costume of King Munza, of Africa, on state occasions. He wore a plumed hat on top of his chignon, reaching one foot and a half above his head. This hat was a narrow cylinder of closely plaited reeds, ornamented with three layers of red parrot feathers and crowned with a plume of the same; it had no brim; he wore a copper crescent in front. His ear muscles were pierced, and copper bars as thick as the finger were in the cavity. His body was smeared, with powdered camwood. His garment of a large piece of fig bark, stained with camwood, reached in graceful folds down the body. Round thongs of buffalo hide, with heavy copper balls at the ends, hung around his waist in a huge knot and, like a girdle, held the coat, which was neatly hemmed. Around the neck hung a copper ornament with little points radiating like beams over the chest; on his bare arms were pendants, in shape like drumsticks, with rings at the end. Half-way up the lower arms and below the knees were three bright, horny-looking circlets of hippopotamus-hide, tipped with copper. In his right hand was a sickle-shaped scimiter of pure copper.

Fig. 9.—South Sea Islander with Liku. width and neatly crimped. Feather garments are frequently of great beauty. The finest come from South America and the south seas. A Mundurucu apron consisted of a backing of cotton string into which were worked feathers: a band of jetty black at the lower end, above it bright yellow, and then scarlet with blue and yellow pattern in it; the upper edge was set with brilliant beetle elytra. The most famous feather mantles were those made for royal use in Hawaii, consisting of mesh-work into which were worked feathers of the yellow melithreptes. Only two of these feathers were produced at one time by one bird, and the mantles were valued at an almost fabulous price. Last of these descriptions we may quote what Schweinfurth says of the costume of King Munza, of Africa, on state occasions. He wore a plumed hat on top of his chignon, reaching one foot and a half above his head. This hat was a narrow cylinder of closely plaited reeds, ornamented with three layers of red parrot feathers and crowned with a plume of the same; it had no brim; he wore a copper crescent in front. His ear muscles were pierced, and copper bars as thick as the finger were in the cavity. His body was smeared, with powdered camwood. His garment of a large piece of fig bark, stained with camwood, reached in graceful folds down the body. Round thongs of buffalo hide, with heavy copper balls at the ends, hung around his waist in a huge knot and, like a girdle, held the coat, which was neatly hemmed. Around the neck hung a copper ornament with little points radiating like beams over the chest; on his bare arms were pendants, in shape like drumsticks, with rings at the end. Half-way up the lower arms and below the knees were three bright, horny-looking circlets of hippopotamus-hide, tipped with copper. In his right hand was a sickle-shaped scimiter of pure copper.

A piece of suitable material for a garment having been secured,  Fig. 10.—Feather Cape and Matting Blanket. New Zealand. the forms would be easily developed. We have already suggested that the close-fitting garments of the northern type of dress arose from the tying on of skins. The present forms of the southern type are almost as simple in their origin. Tylor has suggested a development of forms from the simple blanket or skin robe. The use of the blanket itself we see among many of our Indian tribes today. It is simply thrown over the shoulders, grasped at the sides by the hands, and drawn about the body. If the arms are extended while one wears a blanket in this way, the garment drapes in such a manner as to suggest sleeves. Among some tribes of the Southwest there is a slit made in the center of

Fig. 10.—Feather Cape and Matting Blanket. New Zealand. the forms would be easily developed. We have already suggested that the close-fitting garments of the northern type of dress arose from the tying on of skins. The present forms of the southern type are almost as simple in their origin. Tylor has suggested a development of forms from the simple blanket or skin robe. The use of the blanket itself we see among many of our Indian tribes today. It is simply thrown over the shoulders, grasped at the sides by the hands, and drawn about the body. If the arms are extended while one wears a blanket in this way, the garment drapes in such a manner as to suggest sleeves. Among some tribes of the Southwest there is a slit made in the center of

the blanket and the head is put through this. Such a slit blanket would easily become a loose-sleeved garment, like the one so commonly in use in Guatemala and elsewhere. The Sacs and Foxes in Iowa usually wear the blanket. If a man wishes free use of his hands for work, he folds the blanket through the middle to reduce its length, and wraps it tightly about his waist, tucking the free end tightly in. It thus becomes a skirt, and though skirts usually have not developed in this way, they may have done so sometimes. However a skirt arises, the convenience of a divided skirt sometimes suggests itself, and a pair of loose and flowing trousers results. Thus, from girdles loaded with ornaments and from blankets worn at the shoulders and at the waist, we can see the beginnings of all the forms of the southern dress type. Curiously enough, we ourselves preserve both types of dress. There are two great conservative elements in society—woman and religion.  Fig. 11.—Southern Type of Dress. Japan. Both have served and do serve to-day as useful brakes upon rash and too impetuous change. The northern and the southern types of dress once came in conflict. The time was that of the invasions of the northern barbarians upon imperial Rome. Both men and women, in the ancient days of Rome, wore southern dress. The barbarians wore the tighter-fitting garments of their colder climate. The southern man adopted the more convenient type; the woman did not; and so we see to-day our men in jackets with tight sleeves, and trousers fitting close, while women continue to wear in a modified form the dress of the sunny south—flowing garments, skirts, and cloaks.

Fig. 11.—Southern Type of Dress. Japan. Both have served and do serve to-day as useful brakes upon rash and too impetuous change. The northern and the southern types of dress once came in conflict. The time was that of the invasions of the northern barbarians upon imperial Rome. Both men and women, in the ancient days of Rome, wore southern dress. The barbarians wore the tighter-fitting garments of their colder climate. The southern man adopted the more convenient type; the woman did not; and so we see to-day our men in jackets with tight sleeves, and trousers fitting close, while women continue to wear in a modified form the dress of the sunny south—flowing garments, skirts, and cloaks.

We have no inclination to trace the details of the history of our modern dress. In closing, however, we do wish to call attention to some "survivals" in our garments of to-day. The hatband, with its bow always on the left side, is such a survival. It exists because it once had a real use, and for the position of the knot there is a reason. A hat once was simply a piece of stuff, which was held in place upon the head by binding it with a bit of cord or ribbon. This cord, of course, was tied, and in course of time the knot became large and ornamental. It was the day of sword practice, and such a cockade upon the right side would have interfered with the free use of the weapon; hence the knot must be upon the left side. The band and knot remain, though they have long been useless. Tylor shows us that the dress-coat, the ugly and uncomfortable "swallow-tail" is a survival. It is really the old riding-coat. "The cutting away at the waist had once the reasonable purpose of preventing the coat-skirts from getting in the way in riding, while the pair of useless buttons behind the waist are also relics from the time when such buttons really served the purpose of fastening these skirts behind; the curiously cut collar keeps the now misplaced notches made to allow of its being worn turned up or down; the smart facings represent the old ordinary lining; and the sham cuffs, now made with a seam about the wrist, are survivals from real cuffs, when the sleeves used to be turned back."

We have tried to show that, while three motives have been influential in dress development, the desire for ornament has been the most powerful; that shame for nudeness, though sometimes acting, has been least potent; that two types of dress have been developed; and that our dress is a combination of these two. We have claimed that the desire for dress has urged on man's mental progress, leading to a search for materials and to development of the arts whereby they are made of service. We have considered some examples of dress of no mean workmanship made by low and barbarous tribes. We have inquired how the forms of garments came to be what they are, and have seen that in our own dress much that is useless survives from the past.