Popular Science Monthly/Volume 44/November 1893/Nature at Sea

| NATURE AT SEA. |

By FRANCIS H. HERRICK,

PROFESSOR OF BIOLOGY IN ADELBERT COLLEGE.

IN crossing the seas, as in walking through the fields, there is always the anticipation of making some new discovery. To-day Nature may reveal to us some long-withheld secret. This illusive bird or wild flower which we hitherto missed we now meet face to face. So it is in traversing the great blue fields of the ocean. On this voyage hardly a living object may be seen. The sea-serpent lies low. The captain complains of meeting few sail. Again, on the same track, the winds are fair, the ship makes her course, and the storm cloud no longer baffles the navigator. The inhabitants of the sea show themselves at the surface, and the long days lose their monotony. The voyage is a memorable one in the sailor's calendar.

A good traveler and genuine lover of Nature has the advantage often of turning the rubbish heaps of another to the best account. He finds gold where his companion sees only sand. We can hardly imagine Agassiz or Thoreau (the one representing the scientific, the other the poetic naturalist) at a loss to turn Nature to account anywhere under the sun. Thoreau delves in his Concord meadow and brings up some precious nugget, while Agassiz studies the waterworn pebbles and finds them more interesting than arrowheads. Yet our good observer is, no doubt, put to a severe test at sea, where he may often have occasion to repeat with feeling those familiar lines:

"Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean."

I left Nassau, New Providence, the 1st of July, on a sailing vessel bound for New York. Our boat was a trim schooner of a hundred and fifty tons burden, clean and well ordered, and did credit to this kind of craft. We sailed out of the harbor and crossed the coral bar at high water under a steady southwest breeze which soon drove us out of sight of land and wafted us many miles away in the night.

The Bahaman capital shows to best advantage from the water. Its peak-roofed, chimneyless houses and stuccoed walls of coral stone make a strong contrast with their deep green setting of tropical foliage, the ever-encroaching bush which comes up to the threshold of the town on all sides, and covers these rocky islands with a perpetual mantle of vivid green. The impenetrable maze of the fig and silk-cotton trees, and the looser, stiffer foliage of the almond, add here and there a bolder touch to the landscape, and the unmistakable cocoa palms, seen from afar, adorn the hillside or wave their feathered crests above the beach.

The town skirts the shore for some distance, covering the slope of a low ridge which lies parallel with it. From the brow of the hill an old fort looks down upon the clustering roofs below, upon the white streets, and the dazzling bluish-emerald waters of the bay. A remote fortress half hidden by mantling shrubbery stands guard on a low bluff to the right, while cottages and fishermen's huts, following the main street eastward, dot the shore for several miles on the opposite side. This picturesque little harbor has a livelier appearance to-day than usual. Dingy sponging boats and leaky-looking fishing craft lie along the wharf and down the bay, or are beached at low tide. There are larger vessels bringing ice from Maine, and the iron-gray sides of an English steamer loom

Fig. 1.—Head and Foot of Wilson's Stormy Petrel.

up from yonder low dock, where it now discharges its merchandise fresh from over the sea.

Sailing northeastward, Nassau and its shipping are soon obscured by the long green bar of Hog Island. This is in turn overlapped by similar keys, which gradually fade to green lines and dip under the waves.

For several days the ship speeds on with every sail set. Day and night not a sound is heard but the rustle of waves and the occasional flapping of a sail or sharp report of a rope on the taut canvas. On the sixth day out the sea was nearly calm, like glass, heaving in long, subdued billows, or like a silvered mirror, with slow, undulating tremors spreading far out to the horizon edge.

We noticed that the petrels now rested for the first time on the water after their long journey by wing. These little waifs appear never to alight except in calm weather. Day after day they follow the vessel in search of the stray scraps of greasy food thrown overboard. Now they flit noiselessly alongside, then dash on ahead or fall back astern, and so over the same course again hour after hour for days at a time, without uttering a note or showing the least sign of fatigue.

Dauntless, brave-hearted little bird!—bred in the storm and passing thy life on the ocean wastes. How nimbly you trip along the surging waves, now hid in their deep valleys, or skimming  Fig. 2.—Portuguese Man-of-war. their crests, which you pat with your slender webbed feet, as if to caress them when ready to ingulf you!

Fig. 2.—Portuguese Man-of-war. their crests, which you pat with your slender webbed feet, as if to caress them when ready to ingulf you!

We had not been at sea long before these petrels found us out, and they followed us hundreds of miles. At night I heard, or thought I heard, low, crooning notes from them, but was not sure this mournful sound did not come from some part of the ship's rigging. This is Wilson's petrel (Oceanites oceanicus), named in honor of that great lover of the birds, and well described by him in his American Ornithology. Wilson had an opportunity to study this species while coming by sailing vessel from New Orleans to New York. In order to examine them more particularly he shot a number, notwithstanding the superstitions of the sailors, who lowered a boat and helped him pick them up. These genii of the storm remind you of the swallow, whose graceful movement and power of wing they have, but, unlike the latter, they never soar above the turmoil of the sea. Their plumage is of a nearly uniform sooty-brown hue, excepting the tail coverts, or feathers at the base of the tail, which are snow-white. The physiognomy of the bird is marked by the beak, which points downward, thus enabling it to pick up objects with greater ease from the surface of the water. These delicate, soft-plumaged creatures are the scavengers of the sea. Toss out a few scraps of food, and the object of their comradeship is at once seen. Immediately their quick sense detects it, and all from far and near collect about the floating object, making a little dark cluster on the water. In thus taking their food they never alight, but hover over it, standing tiptoe on the wave or lifting their delicate black feet up and down as if dancing on the water. From this characteristic performance the name petrel is said to be derived from Saint Peter, in allusion to the story of his walking on the sea.

This and the rarer stormy petrel and a third species, which all resemble one another very closely, are commonly known to sailors as "Mother Carey's chickens," a name quite generally applied  Fig. 3.—Common Porpoise. to this family, and probably suggested, as Wilson observes, by their mysterious appearance before and during storms, their great power of flight, and obscure habits. The superstitious mariner may indeed have regarded his little comrades not as harbingers merely, but as agents in league with the powers of darkness, directly concerned in bringing the storm. Mother Carey is the mater cara; so with the French these birds are "oiseaux de Notre Dame." The gigantic fulmar of the Pacific is known as "Mother Carey's goose," and hence the phrase "Mother Carey is plucking her goose"—that is, "it is snowing."

Fig. 3.—Common Porpoise. to this family, and probably suggested, as Wilson observes, by their mysterious appearance before and during storms, their great power of flight, and obscure habits. The superstitious mariner may indeed have regarded his little comrades not as harbingers merely, but as agents in league with the powers of darkness, directly concerned in bringing the storm. Mother Carey is the mater cara; so with the French these birds are "oiseaux de Notre Dame." The gigantic fulmar of the Pacific is known as "Mother Carey's goose," and hence the phrase "Mother Carey is plucking her goose"—that is, "it is snowing."

While the petrels do not "carry their eggs under their wings and hatch them while resting on the sea," as seafaring men affirmed, yet their domestic life seems to be curtailed as much as possible. They nest in cavities in rocks along the coast or in burrows in the ground, laying a single white egg. This species is said to breed in Florida and the West India islands.

The petrel belongs to the wild wastes of the sea, as the gull belongs to the shore, and the swallow to inland districts. Sea birds are as completely helpless when driven far inland as the  Fig. 4.—Salpa. strictly land species are at sea. Every now and then we hear of some wanderer from the coast being picked up half dead from exhaustion and fright hundreds of miles from the ocean, having been shipwrecked apparently and blown in thither during a storm. A case of this kind was communicated to me some time ago by a gentleman in Sharon, Vermont, where a specimen of the dovekie, or sea dove, a common bird of the northern New England coast, was found one morning in the fall on a neighbor's porch.

Fig. 4.—Salpa. strictly land species are at sea. Every now and then we hear of some wanderer from the coast being picked up half dead from exhaustion and fright hundreds of miles from the ocean, having been shipwrecked apparently and blown in thither during a storm. A case of this kind was communicated to me some time ago by a gentleman in Sharon, Vermont, where a specimen of the dovekie, or sea dove, a common bird of the northern New England coast, was found one morning in the fall on a neighbor's porch.

The helplessness of our song birds when carried to sea is pitiable in the extreme. I rarely make a voyage of any length but some small bird is shaken out of a sail where it hid in its fright, or is found taking refuge in the rigging. Once, while off Cape Hatteras, a finch or sparrow of some species came aboard our schooner, showing great fatigue and fear by its tremulous, hesitating flight. Its small wings were of little avail to cope with the wide blue expanse on which distance is so deceptive. It fluttered about from rope to spar, glad to find "rest for the sole of its foot," and although it made short detours reconnoitring sallies now and then from the boat—I think it invariably returned, and decided to take passage with us to the land.

On a calm evening I saw another larger bird looking like a petrel, swimming about with Mother Carey's chickens. It had long, swordlike wings, and was of a dark slate color above and below pure white. Once a pair of tropic birds crossed our track. We frequently catch glimpses of the bold shearwaters skimming the distant seas, and hear their piercing cries as they dart along  Fig. 5.—Flying Gurnard. the waves, now lost in the trough of the sea or soaring aloft, their breasts white as the foam below.

Fig. 5.—Flying Gurnard. the waves, now lost in the trough of the sea or soaring aloft, their breasts white as the foam below.

How welcome is every unusual sight and sign of life on the desert sea plains! The great schools of fish ruffling the surface, now and then leaping into full view; the sleek porpoises showing their powerful tails or racing the ship under her bows; the chance shark which dogs the vessel; the splendid physalias, or Portuguese men-of-war. How eagerly the sailor scans the horizon to catch a glimpse of a sail, and the discovery is soon known to every one on board! A mere phantom to an ordinary eye, he tells whether it be schooner, bark, or brig, knows her course, perhaps also where she is bound and what she carries. Now we see the topmasts only of some vessel standing off on the horizon, or the gray form of a ship half screened by the fog. Now a steamer passes us, and the thud of the wheel and clang of its foghorn are heard long after it vanishes in the mist.

I never saw the physalia so abundant as on one afternoon of this voyage. The surface of the sea heaved in long, gentle swells. At times a dozen of these little sails could be counted from the vessel. Those farthest away appear as white, glistening specks. One, unusually large and handsome, floats near by. It looks like a diminutive boat blown out of iridescent glass. Its transparent, gleaming sail, gathered at the edge, is tinged with pink and blue next the water. Once we dipped one in a net, and placing it carefully in a pail of sea-water, examined it at our leisure on deck. It was then seen to consist of a float or air bag, and thick clusters of pink bodies attached, and longer blue ones which extend down in the water.

Our little man-of-war bears a truer resemblance to a well manned and ordered warship than might at first be supposed, since it is not an individual, but a community of polyp-like animals

Fig. 6.—Antennarius.

bound together for common support and protection, with a division of labor recalling that maintained aboard a vessel, or, better still, like that seen in a hive of bees. There are four kinds or grades of persons in the physalia community. There are the feeders, the pink bodies just mentioned, which procure and digest the food for the whole community, all the polyps communicating freely with each other; the defenders, the long, indigo-colored tentacles, which may be distended like flexible threads to the length of several yards, and which are covered all over with batteries of poison cells, a touch from which is like the sting of a dozen nettles; the reproducers are the very small polyps at the bases of the tentacles; while the locomotor float represents a polyp or hydra which has become modified the most of all. This float, like a miniature sail, may be raised or reefed by admitting or expelling the air, and if punctured it collapses like a toy balloon.

The physalias are hydrozoa—that is to say, they belong to that large class of marine forms which include, with the little

Fig. 7.—Ship in Phosphorescent Waters.

green and brown hydras of fresh-water ponds, the highly colored or glass-like jellyfish or medusæ, and those numerous hydroid colonies or branching stocks which often remind one more of small shrubs or some vegetable growth than of a community of animals. Many hydrozoa possess marvelously complicated life histories. By "alternation of generations"—that is, by the regular alternation of a sexual generation with one or more generations reproducing asexually by budding or division—and by division of labor, an almost unlimited number of individuals with various functions, as we saw in physalia, may arise from a single polyp egg.

Porpoises bent upon voyages of their own pass us at intervals. At each turn in the water we see their huge fins and shining, convex bodies. The porpoise describes a graceful, undulatory line in its course through the water; now appearing at the surface and immediately diving below it, showing itself only as it rounds the crest of each wave. When a number rise together in line, their dorsal fins and backs alone being visible, you are reminded of a great saw with huge, incurved teeth. Here, again, are others apparently at play. How they lash the water into spray with their powerful tails! Now one shoots like an arrow into the air; another jumps, and clearing the water for several feet, enters it again with a plunge. This may be anything but play, however. A whale or some other enemy is perhaps giving them chase, and they are fleeing for their lives.

We saw several whales during this voyage, and on one evening two crossed our bows. They swam side by side, rolling along at an easy gait, much like that of the porpoise, and spouting a jet of spray as they came to the surface to breathe.

At another time a very large school of porpoises was seen advancing toward our vessel. There must have been several hundred of them. They formed a long, not very deep line, swimming in several squads of fifty or more each, and crossed our course without altering theirs. Some passed by the stem or bow, or with a plunge shot under the vessel as if it were a plank. Both dolphins and porpoises like to race with a ship, although it costs many their lives. You can see their brown, spotted bodies and blunt noses as with great speed they shoot to this and that side of the cutwater. The faster the ship goes the greater seems to be the sport. The porpoise is little more than a powerfully muscular tail, developed at the expense of the rest of the body. Most sailing craft carry a spear or harpoon, for the sailors not only like the excitement of taking these animals, but also find in their flesh a welcome variety to the monotonous ship fare.

One morning, as I stood with the captain on the forecastle deck, he attaching his harpoon line as I watched the porpoises, I saw a large loggerhead turtle under the bow, his brown back being barely under water. He appeared to be asleep, but in a moment the vessel struck him, and down he slowly paddled out of sight. The spear did not happen to be in readiness, so that our turtle soup that day was a strictly Barmecide dish.

The number of small invertebrate animals which come to the surface on calm evenings is quite astonishing. Once in May, while in the vicinity of the Gulf Stream, near the Florida coast, there appeared regularly at about four o'clock in the afternoon countless swarms of a brown jellyfish or medusa—"sea thimbles," as sailors call all animals of this class—and this species (Linerges) is about the size of a thimble. The clear indigo water was speckled with them. You could dip them up anywhere in a bucket, and we sailed miles without noticing any appreciable diminution in their numbers. This and like spectacles give us a

Fig. 8.—Luminous Fishes.

faint conception of the incalculable wealth of the sea in living things, and of their superabundance if allowed to multiply unchecked.

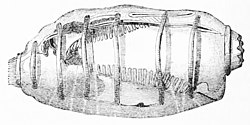

Another marine organism seen floating near the surface is three or four inches long and looks like a little roll of white lace with a pink spot in the center. This is a species of salpa, which belongs to the class of Ascidians, and is especially noteworthy since its embryonic history bears a strong resemblance to that of the lower vertebrates. The life history of the salpas is greatly complicated by the process of alternation of generations seen in physalia, and it was in them, in fact, that this phenomenon was first noticed.

The flight of the flying fish recalls that of some insects. When a ship plows through a school of these creatures, how they scud off on all sides like grasshoppers rising from underfoot in the fields, and by the aid of their gauze wings, the pectoral and ventral fins, fly to a place of safety! From the indistinct halo seen about these fish in flight, from the abrupt turns which they execute, going as readily against the wind as with it, and from their apparently uniform speed, we naturally infer a rapid beating of those delicate wings, as in the case of humming birds and certain insects, and this inference is probably a correct one. Many observers, however, contend that this is not a genuine flight, but scaling. According to this view, the fish project themselves with a great velocity from the water, press with their wings, held at an advantageous angle, against the air, and are thus kept up, while they are carried forward by their own inertia. Their motion would thus be gradually retarded until they finally entered the water again, like that of a stone skimmed along the surface of a pond, while on the contrary their flight appears to be quite uniform. This and other mechanical difficulties, and the fact that the beating of the fins can be clearly seen in other species of flying fish, show that the common belief that these animals fly in the strict sense of the word is probably the true one.

The vegetation of the sea is limited to the brown masses of sargassum or "gulf weed," which is most abundant in or along the borders of the Gulf Stream and may be seen growing on the sheltered reefs about Nassau. This alga is especially interesting for the wealth of marine life which it shelters. A large mass, which has been a floating island for some time, possesses in fact quite a varied fauna. If you fish up a handful of it and shake it over the deck, the little animals pour down like rain. Here are crabs and shrimps without number, some of them very delicate, no longer than a pin; barnacles, mollusks, and fish of several species, one of which, the Antennarius, regularly lives and builds its nest in these little islands. This grotesque fish is two or three inches long and nearly as broad in a vertical plane, and is variously spotted and mottled with light and dark-brown colors. Its lower fins resemble a pair of hands in shape and function, and its head recalls that of a mediæval war horse armed and plumed.

These little communities furnish a striking instance of the protective coloring of animals, a phenomenon of which there

Fig. 9.—A Submarine View of the Shore at Nassau. A sand bottom near a sheltered reef with loggerhead sponges (Hircinia arcuta) in the foreground, and buds of seaweed, sprinkled with large white "sea eggs" or sea urchins (Hipponæ). Trunkfish (Ostracion) are swimming above.

The salpas and medusæ are beautifully phosphorescent at night, and in fact most of the invertebrate life of the sea, which on calm evenings swarms in myriads at the surface, possesses this remarkable power. Then is every ripple followed by a train of glowing sparks, every wave which breaks against the ship by a brilliant meteoric shower. The larger medusæ, which look like softly glowing balls of mystic fire, and the barrel-shaped ctenophores are stars of the first magnitude, while behind there is a whole galaxy of lesser lights, to count which would be much like counting the stars. As I sat one evening watching our rudder, after which trailed a long, curling line of sparks, four small fish made their appearance and swam by the stern for several hours. Their forms were illumined in the black water, and a train of fire followed each as like little meteors they darted after the ship.

We can form at most but a very imperfect idea of the life of the sea from the chance glimpses afforded on the most favorable voyage. We see but transient tokens of that vast life which the sea holds in her teeming bosom.

Could we project vertical sections of the ocean upon a screen and examine these pictures in detail, what revelations might they not unfold! We would have the dwellers in every story of the sea caught in their natural attitudes, the hosts of smaller animals at the surface, the many fish and other monsters of the deep, and those far off dwellers in the abyssal sea. Scientific study with the microscope, the tow-net, and deep-sea dredge is revealing little by little those wonderful forms of life which have been so long hidden from human eyes.