Popular Science Monthly/Volume 5/May 1874/The Grape Phylloxera

THE

POPULAR SCIENCE

MONTHLY.

MAY, 1874.

| THE GRAPE PHYLLOXERA. |

By CHAS. V. RILEY, M. A., Ph. D.

THIS is an insect which is attracting much attention just now, and which has held a very prominent place in economic entomological literature during the past five years. It has occurred to me that it would not be uninteresting to the many readers of The Popular Science Monthly to have the facts now known about it laid before them in a popular form, and with as little of the nomenclature of science as is consistent with precision. I therefore transmit the following advance matter from the forthcoming sixth "Entomological Report of Missouri," very slightly modified to adapt it to the pages of the Monthly.

To many the term "Phylloxera" is void of meaning, so that it may not be amiss to say, at the outset, that it is a term derived from the Greek (øύλλον and ξηρός), meaning withered-leaf, and founded many years ago,[1] by Boyer de Fonscolombe, to designate a peculiar genus of plant-lice. It was originally erected for a species (Phylloxera quercus) quite common in Europe on the under side of oak-leaves, which, in consequence of its punctures, wear a withered appearance. The genus now comprises several species, none of them affecting man's interests except the species under consideration (vastatrix Planchon). This, on account of its injurious work, has acquired such prominence that the generic term has come to be used in a broader sense, and to indicate at once the insect and the disease it produces; just as in botany the term oidium, though originally referring only to a genus of cryptogamic plants, is now popularly employed to designate the mildew on grape-vines, caused by Oidium Tuckeri.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL.

The first published reference to this insect was made in the year 1856,[2] by Dr. Asa Fitch, the State Entomologist of New York, who subsequently described the gall-inhabiting type of it, which I have termed gallæcola in a rather insufficient manner,[3] by the name of Pemphigus vitifoliæ. Dr. Fitch knew very little of the insect, as we understand it to-day. It was subsequently treated of by several American authors, and in January, 1867, Dr. Henry Shimer, of Mount Carrol, III, proposed for it a new family Daktylosphæridæ),[4] which has not been accepted by homopterists, for the reason that it was founded on characters of no family value.

All these authors referred to the leaf-louse described by Dr. Fitch, and never dreamed that the insect existed in another type on the roots. During the few years following our civil war a serious disease of the Grape-vine began to attract attention in France, and soon caused so much alarm that the Minister of Agriculture and Commerce in that country offered a prize of 20,000 francs for an effectual and practicable remedy; and a special committee was appointed to draw up a programme of conditions, and award the prize if it saw fit so to do.

The disease is known as pourridie, or rotting, the roots becoming swollen and bloated, and finally wasting away. There were no end of surmises and theories as to its cause, until Prof. J. E. Planchon, of Montpellier, in July, 1868, announced[5] that it was due to the puncture of a minute insect belonging to the plant-louse family (Aphididæ), and bearing a close resemblance to our gall-louse. The insect was subsequently described, by the same author, from the apterous form, under the name of Rhizaphis vastatrix, and not till September of the same year[6] when the winged insect was discovered, did he give it the name by which it is now so well known. In January, 1869, Prof. J. O. Westwood, of Oxford, England, announced[7] the receipt of both the gall and root-inhabiting types, from different parts of England and Ireland, and his inability to distinguish between the two. In the same article he announced having received the gall-making type from Hammersmith in 1863, and having described it by the name of Peritymbia vitisana, in a notice communicated to the Ashmolean Society of Oxford, in the spring of 1868, which communication was, I believe, never published. In the spring of 1869,[8] M. J. Lichtenstein, of Montpellier, first hazarded the opinion that the Phylloxera, which was attracting so much attention in Europe, was identical with the American insect described by Dr. Fitch. This opinion gave an additional interest to our insect, and I succeeded in 1870, while the Franco-Prussian war was at its highest, and just before the investment of Paris, in establishing the identity of their gall-insect with ours, through correspondence with, and specimens sent to. Dr. V. Signoret, of that city. During the same year I also established the identity of the gall and root-inhabiting types, by showing that in the fall of the year the last brood of gall-lice betake themselves to the roots and hibernate thereon. In 1871 I visited France and studied their insect in the field; and in the fall of that year, after making more extended observations here, I was able to give absolute proof of the identity of the two insects, and to make other discoveries, which not only interested our friends abroad, but were of vital importance to our own grape-growers, especially in the Mississippi Valley. I have given every reason to believe that the failure of the European vine (Vitis vinifera) when planted here, the partial failure of many hybrids with the European vinifera and the deterioration and death of many of the more tender-rooted native varieties, are mainly owing to the injurious work of this insidious little root-louse. It had been at its destructive work for years, producing injury the true cause of which was never suspected until the publication of the article in the "Fourth Entomological Report of Missouri." I also showed that some of our native varieties enjoyed relative immunity from the insects' attacks, and urged their use for stocks, as a means of reestablishing the blighted vineyards of Southern France.

The disease continued to spread in Europe, and became so calamitous in the last-named country that the French Academy of Science appointed a standing Phylloxera Committee. It is also attracting some attention in Portugal, Austria, and Germany, and even in England, where it affects hot-house grapes.

The literature of the subject grew to such vast proportions that, after publishing a biographical review, containing notices and summaries of 484 articles or treatises published during the four years of 1868-'71, MM. Planchon and Lichtenstein gave up the continuance of the work as impracticable.

At the suggestion and with the coöperation of the Société Centrale d'Agriculture de l'Hérault, the French Minister of Agriculture last autumn commissioned Prof. Planchon to visit this country and learn all he could about the insect and its effects on our different vines. Prof. Planchon arrived here the latter part of August and remained over a month, during which time he visited many prominent vineyards in the Eastern States, on Kelley's Island, in Missouri, and in North Carolina. His investigations not only fully corroborated all my previous conclusions regarding the Phylloxera, but gave him a knowledge of the quality of our native grapes and wines which will be very apt to dispel much of the prejudice against them that has so universally possessed his countrymen, who have not followed our recent rapid progress in viticulture and viniculture, but found their opinions on the inferior results which attended the infancy of those industries in America. Such, in brief, is the history of the grape Phylloxera. Let us now take a closer insight into the nature of the insect.

The genus Phylloxera is characterized by having three-jointed antennæ, the third or terminal much the longest, and by carrying its wings overlapping flat on the back instead of roof-fashion. It belongs to the whole-winged bugs (Homoptera), and osculates between two great families of that sub-order, the plant-lice (Aphididæ) on the one hand and the bark-lice (Coccidæ) on the other. In the one-jointed tarsus of the larva or newly-hatched louse, and in being always oviparous, it shows its affinities with the latter family; but in the two-jointed tarsus of the more mature individuals, and in all other characters, it is essentially aphididan. "In every department of natural history a species is occasionally found which forms the connecting link between two genera, rendering it doubtful under which genus it should properly be arranged. Under such circumstances the naturalist is obliged to ascertain by careful examination the various predominating characteristics, and finally place it under the genus to which it bears the closest affinity in all its details." So wrote Audubon and Bachman twenty-eight years ago;[9] and what is true of genera is equally true of species, families, and of still higher groups. In the deepest sense all Nature is a whole, and all her multitudinous forms of animal and vegetal life are so closely interlinked, and graduate into each other so insensibly, that in founding divisions on too trivial differences we subvert the objects of classification. Thus, instead of founding a new family for this insect, as Dr. Shimer did, and as there seems a tendency on the part of others to do, it is both more consonant with previous custom, and more sensible in every way, to retain it among the Aphididæ.

BIOLOGICAL.

Different Forms which the Insect assumes.—Not the least interesting features in the economy of our Phylloxera are the different phases or forms under which it presents itself. Among these forms are two constant types which have led many to suppose that we have to do with two species. The one type, which I have, for convenience, called gallæcola, lives in galls on the leaves; the other, which I have called radicicola on swellings of the roots. The subjoined table will assist to a clear understanding of what follows.

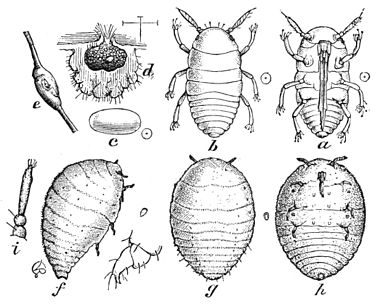

Type 1. Gallæcola. (Vitifoliœ, Fitch. Fig. 3, f, g, h.)

Type 2. Radicicola.—

a, Degraded or Wingless Form. (Fig. 4, e, f, g.)

β, Perfect or Winged Form. (Fig. 5, g, h; Fig. 7, b.)

Type Gallæcola or Gall-inhabiting.—The gall or excrescence produced by this insect is simply a fleshy swelling of the under side of the leaf, more or less wrinkled and hairy, with a corresponding depression of the upper side, the margin of the cup being fuzzy, and drawn together so as to form a fimbriated mouth. It is usually cup-shaped, but sometimes greatly elongated or purse-shaped (Fig. 2, a, b).

Soon after the first vine-leaves that put out in the spring have fully expanded, a few scattering galls may be found, mostly on the lower leaves, nearest the ground. These vernal galls are usually large (of the size of an ordinary pea), and the normal green is often blushed with rose where exposed to the light of the sun. On opening one of them (Fig. 3;d) we shall find the mother-louse diligently at work surrounding

Fig. 1.

Leaf covered with Galls.

herself with pale-yellow eggs of an elongate oval form, scarcely .01 inch long, and not quite half as thick (Fig. 3, c). She is about .04 inch long, generally spherical in shape, of a dull orange-color, and looks not unlike an immature seed of the common purslane. At times, by the elongation of the abdomen, the shape assumes, more or less perfectly, the pyriform. Her members are all dusky, and so

Fig. 2.

a and b, elongated galls; c and d, upper and under side of abortive galls.

short compared to her swollen body, that she appears very clumsy, and undoubtedly would be outside of her gall, which she never has occasion to quit, and which serves her alike as dwelling-house and coffin. The eggs begin to hatch, when six or eight days old, into active little oval, hexapod beings, which differ from their mother in their brighter yellow color and more perfect legs and antennae, the tarsi being furnished with long, pliant hairs, terminating in a more or less distinct globule. These hairs were called digituli by Dr. Shimer, and they lose their globular tips and become more or less worn with age. Issuing from the mouth of the gall, these young lice scatter over the vine, most of them finding their way to the tender terminal leaves, where they settle in the downy bed which the tomentose nature of these leaves affords, and commence pumping up and appropriating the sap. The tongue-sheath is blunt and heavy, but the tongue proper––consisting of three brown, elastic, and wiry filaments, which, united, make so fine a thread as scarcely to be visible with the strongest microscope––is sharp, and easily run under the parenchyma of the leaf. Its puncture causes a curious change in the tissues of the leaf, the

Fig. 3.

Type Gallæcola.—a, b, newly-hatched larva, ventral and dorsal view; c, egg; d, section of gall; e, swelling of tendril; f, g, h, mother gall-louse—lateral, dorsal, and ventral views; i, her antenna; j, her two-jointed tarsus. Natural sizes indicated at sides.

growth being so stimulated that the under side bulges and thickens, while the down on the upper side increases in a circle around the louse, and finally hides and covers it as it recedes more and more within the deepening cavity. Sometimes the lice are so crowded that two occupy the same gall. If, from the premature death of the louse, or other cause, the gall becomes abortive before being completed, then the circle of thickened down or fuzz enlarges with the expansion of the leaf, and remains (Fig. 2, c) to tell the tale of the futile effort. Otherwise, in a few days the gall is formed, and the inheld louse, which, while eating its way into house and home, was also growing apace, begins a parthenogenetic maternity by the deposition of fertile eggs, as her immediate parent had done before. She increases in bulk with pregnancy, and one egg follows another in quick succession, until the gall is crowded. The mother dies and shrivels, and the young, as they hatch, issue and found new galls. This process continues during the summer until the fifth or sixth generation. Every egg brings forth a fertile female, which soon becomes wonderfully prolific. The number of eggs found in a single gall averages about 200; yet it will sometimes reach as many as 500, and, if Dr. Shimer's observations can be relied on, it may even reach 5,000.[10] I have never found any such number myself; but, even supposing there are but five generations during the year, and taking the lowest of the above figures, the immense prolificacy of the species becomes manifest. Small as the animal is, the product of a single year, even at this low estimate, would encircle the earth over thirty times if placed in a continuous line, each individual touching the end of another. Well it is for us that they are not permitted to multiply in this geometrical ratio! Nevertheless, as summer advances, they do frequently become prodigiously multiplied, completely covering the leaves with their galls, and settling on the tendrils, leaf-stalks, and tender branches, where they also form knots and rounded excrescences (Fig. 3, e), much resembling those made on the roots. In such a case, the vine loses its leaves prematurely. Usually, however, the natural enemies of the louse seriously reduce its numbers by the time the vine ceases its growth in the fall, and the few remaining lice, finding no more succulent and suitable leaves, seek the roots. Thus, by the end of September, the galls are mostly deserted, and those which are left are almost always infested with mildew [Botrytis viticola, Berkely), and eventually turn brown and decay. On the roots, the young lice attach themselves singly or in little groups, and thus hibernate. The male gall-louse has never been seen, and there is every reason to believe that he has no existence. Nor does the female ever acquire wings. Indeed, I cannot lay too much stress on the fact that gallæcola occurs only as an agamic and apterous female form. It is but a transient summer state, not at all essential to the perpetuation of the species. I have found it occasionally on all species of the Grape-vine (vinifera, riparia æstivalis, and Labrusca) cultivated in the Eastern and Middle States, and on the wild Cordifolia; but it flourishes only on the River-bank grape (riparia), and more especially on the Clinton and Taylor, with their close allies. Thus, while legions of the root-inhabiting type (radicicola) are overrunning and devastating the vineyards of France, this gallæcola is almost unknown there, except on such American varieties as it infests with us. A few of its galls have been found at Sorgues, on a variety called Tinto; and others have been noticed on vinifera vines interlocking infested American vines, or have been produced by purposed contact with the young gallæcola. Similarly, there are many varieties, especially of Labrusca, which, in this country, suffer in the roots, and never show a gall on the leaves.

The precise conditions which determine the production and multiplication of gallæcola cannot now, if they ever can, be stated; but it is quite evident that the nature and constitution of the vine are important elements, since such vines as the Herbemont often bear witness, by their leaves covered with abortive galls, to the futile efforts the lice sometimes persist in making to build in uncongenial places.

Yet other elements come into play, and nothing strikes the observer as more curious and puzzling than the transitory nature of these galls, and the manner in which they are found—now on one variety, now on another.

I was formerly inclined to believe that gallæcola was a necessary phase in the annual cycle of the insect's mutations; in other words, that it was essential to the continuance of the species, and was probably the product of the egg laid by the winged and impregnated female. On this hypothesis I imagined that gallæcola was probably the invariable precursor of radicicola in an uninfested vineyard, and that, if galls were not allowed to develop in such a vineyard, it would not suffer from root-lice. More extensive experience has satisfied me that the hypothesis is essentially erroneous, and that, while the first galls may sometimes be produced by lice hatched from the few eggs deposited above-ground by the winged female, they are more often formed by young lice hatched on the roots, and which, wandering away from their earthy recesses, are fortunate enough to find suitable leaf conditions. It is barely possible that under certain circumstances, as, for instance, on our wild-vines, where the soil around the roots is hard and compact, gallæcola may become more persistent, and pass through all the phases belonging to the species without descending to the roots—the eggs wintering on the ground, or the young under the loose bark, or upon the canes. For a somewhat similar state of things actually takes place with another plant-louse (Eriosoma pyri Fitch), which in the Western United States normally inhabits the roots of our apple-trees, and only exceptionally the branches; while in the moister Atlantic States, and in England and moister parts of Europe, where it was introduced from this country, it normally infests the branches, and more exceptionally the roots. But there are no facts yet known to prove such to be the case with the Grape Phylloxera, even on our wild-vines, and I do not believe that it ever is the case in our cultivated vineyards.

As already indicated, the autumnal individuals of gallæcola descend to the roots, and there hibernate. There is every reason to believe also that, throughout the summer, some of the young lice hatched in the galls are passing on to the roots; as, considering their size, they are great travelers, and show a strong predisposition to drop, their natural lightness, as in the case of the young Cicada, and of other insects which hatch above but live under ground, enabling them thus to reach the earth with ease and safety. At all events, I know, from experiment, that the young gallæcola, if confined to vines on which they do not normally, and perhaps cannot, form galls, will, in the middle of summer, make themselves perfectly at home on the roots.

Type Radicicola or Root-Inhabiting.—We have seen that, in all probability, gallæcola exists only in the apterous, shagreened, non-tubercled, fecund female form. Radicicola, however, presents itself in two principal forms. The newly-hatched larvæ of this type are undistinguishable, in all essential characters, from those hatched in the galls; but in due time they shed the smooth larval skin, and acquire raised warts or tubercles which at once distinguish them from gallæcola. In the development from this point two forms are separable with sufficient ease, one (a) of a more dingy greenish-yellow, with more swollen fore-body, and more tapering abdomen; the other (ß) of a brighter yellow, with the lateral outline more perfectly oval, and with the abdomen more truncated at tip.

Fig. 4.

Type Radicicola.—a, roots of Clinton vine, showing relation of swellings to leaf-galls, and power of resisting decomposition; b, larva as it appears when hibernating; c, d, antenna and leg of same; e, f, g, forms of more mature lice.

The first or mother form (Fig. 4, f, g,) is the analogue of gallæcola, as it never acquires wings, and is occupied, from adolescence till death, with the laying of eggs, which are less numerous and somewhat larger than those found in the galls. I have counted in the spring as many as 265 eggs in a single cluster, and all evidently from one mother, who was yet very plump and still occupied in laying. As a rule, however, they are less numerous. With pregnancy this form becomes quite tumid and more or less pyriform, and is content to remain with scarcely any motions in the more secluded parts of the roots, such as the creases, sutures, and depressions, which the knots afford. The skin is distinctly shagreened (Fig. 4, h), as in gallæcola. The warts, though usually quite visible with a good lens, are at other times more or less obsolete, especially on the abdomen. The eyes, which were quite perfect in the larva, become more simple with each moult, until they consist, as in gallæcola, of but triple eyelets (Fig. 4, k), and, in the general structure, this form becomes more degraded with maturity, wherein it shows the affinity of the species to the Coccidæ, the females of which, as they mature, generally lose all trace of the members they possessed when born.

The second or more oval form (Fig. 4, e) is destined to become winged. Its tubercles, when once acquired, are always conspicuous;

Fig. 5.

Type Radicicola.—a, shows a healthy root; b, one on which the lice are working, representing the knots and swellings caused by their punctures; c, a root that has been deserted by them, and where the rootlets have commenced to decay; d, d, d, show how the lice are found on the larger roots; e, female pupa, dorsal view; f, same, ventral view; g, winged female, dorsal view; h, same, ventral view; i, magnified antenna of winged insect; j, side view of the wing-less female, laying eggs on roots; k, shows how the punctures of the lice cause the larger roots to rot.

it is more active than the other, and its eyes increase rather than diminish in complexity with age. From the time it is one-third grown, the little dusky wing-pads may be discovered, though less conspicuous than in the pupa state, which is soon after assumed. The pupæ (Fig. 5, e,f) are still more active, and, after feeding a short time, they make their way to the light of day, crawl over the ground and over the vines, and finally shed their last skin and assume the winged state. In this last moult the tubercled skin splits on the back, and is soon worked off, the body in the winged insect having neither tubercles nor granulations. These winged insects are most abundant in August and September, but may be found as early as the first of July, and until the vines cease growing in the fall. The majority of them are females, with the abdomen large, and more or less elongate. The veins of the front wing are not connected (Fig. 6, a), and, by virtue of the large abdomen, the body appears somewhat constricted behind the thorax. From two to five eggs may invariably be found in the abdomen of these, and are easily seen when the insect is held between the light, or mounted in balsam or glycerine. A certain proportion have an entirely different shaped and smaller body, the abdomen being short, contracted, and terminating in a fleshy and dusky penis-like protuberance, the limbs stouter, and the wings proportionally larger and stouter, with

Fig. 6.

Pterogostic Characters.—a, b, different venation of front-wing; c, hind-wing; d, e, f, showing development of wings.

their veins connecting (Fig. 6, b). This shorter form (Fig. 7, b) never has eggs in the abdomen, but, instead, a number of vesicles (Fig. 7, e), containing granulations in sacs. These granulations have much the appearance of spermatozoa, and seem to have a Brownian movement, but are without tails.

This form has been looked upon as the male by myself, Planchon, Lichtenstein, and others. Yet I have never succeeded in witnessing it perform the functions of the male, nor has any one else that I am aware of. The males in all plant-lice are quite rare, and, in the great majority of species, unknown. Where known, this sex bears about the same relation to the female as the shorter and smaller Phylloxera just described does to the larger. These same differences observed in the winged insects obtain in the other species of the genus that are known, and have always been looked upon as sexual. Signoret, an authority on these insects, once so looked upon them,[11] but has lately declared the shorter form to be a female emptied of her eggs. If this be so, then the eggs must be laid before the insect arrives at maturity (a highly improbable circumstance); for the characteristics which distinguish it are to be noticed in the pupa (Fig. 7, a), which is almost as broad as long, with very large wing-pads and strong limbs; while the winged insect does not, as we have seen, carry any eggs. But, whatever the true nature and functions of these problematic and gynandrous individuals, it would seem, from some exceedingly interesting observations lately made by Balbiani,[12] that they cannot be males, if there be any such thing as unity of habit and character among the species of the genus. Balbiani has made the curious discovery, in the annual development of Phylloxera quercus that the winged individuals, which appear in August, fly off to new leaves and deposit their

Fig. 7.

Type Radicicola.—a, b, pupa and image of a gynandrous individual, or supposed male; c, d, its antenna and leg; e, vesicles found in abdomen.

unimpregnated eggs, to the number of five to eight. These eggs are of two different sizes, the smaller being readily separated from the larger. They hatch in about a dozen days, the smaller giving birth to males, and the larger to females, which have neither mouth-parts nor digestive organs, and neither grow nor moult after birth. The sole aim of their existence is the reproduction of the species, and they crawl actively about and gather in little multitudes in the crevices and interstices which are afforded them. The male, except in size, seems to differ from the female only in having a small conical tubercle, which serves as sexual organ. Coitus lasts but a few minutes, and the same male may serve several females. Four or five days after birth the female lays a solitary egg, which, increasing somewhat after impregnation, had caused her abdomen to swell and enlarge a little prior to oviposition. Two or three days after this operation the mother dies; but the males live as long again.

This solitary egg, which Balbiani calls the winter-egg, soon takes on a dark color, which indicates its fecundity and distinguishes it from parthenogenetic eggs of both the winged and wingless females. It is surmised that this egg passes the winter to give birth in spring to the form destined to recommence the cycle of development belonging to the species.

These discoveries are truly remarkable, and appear to me all the more so since Balbiani[13] likewise found that the individuals which never become winged attain maturity without laying eggs on the leaves on which they were born, but crawl on to the branches and in the interstices of the old scales at the base of the new year's growth. There they lay a number of eggs, which are absolutely like those deposited by the winged females, and, like them produce the sexual individuals i. e., both males and females. Now, this does not correspond with what I have seen myself of the species, or with what has been described by others; for the apterous individuals of quercus surround themselves with eggs on the leaves where they are born.

M. Max-Cornu has already announced having found a sexual individual, without mouth-parts, of the Grape Phylloxera; and it is quite likely, now that Balbiani has paved the way, that we shall next year have its natural history complete. But whether the Grape Phylloxera produces this fecundated and solitary egg or not, such an egg is neither essential to its winter life, nor to that of an American species (Phylloxera Rileyi Lichtenstein), which will be described farther on, and which is, in every respect, very closely allied to the European quercus.

While, therefore, there is much yet to learn in the life-history of our Grape Phylloxera, the facts which I have already unequivocally stated, as well as those which I shall now proceed to give, remain indisputable, and do not seem fully to accord with Balbiani's discoveries.

As fall advances the winged individuals become more and more scarce, and as winter sets in only eggs, newly-hatched larvae, and a few apterous egg-bearing mothers, are seen. These last die and disappear during the winter, which is mostly passed in the larva state, with here and there a few eggs. The larvæ thus hibernating (Fig 4, b) become dingy, with the body and limbs more shagreened and the claws and digituli less perfect than when first hatched; and, of thousands examined, all bear the same appearance and all are furnished with strong suckers. As soon as the ground thaws and the sap starts in the spring, these young lice work off their winter coat, and, growing apace, commence to deposit eggs. All, without exception, so far as I have seen,[14] become mothers and assume the degraded form (a) already described.

At this season of the year, with the exuberant juices of the plant, the swellings on the roots are large and succulent and the lice plump to repletion. One generation of the mother form (a) follows another—fertility increasing with the increasing heat and luxuriance of summer—until at least the third or fourth has been reached before the winged form (β) makes its appearance in the latter part of June or early in July.

Such are the main features which the development of the insect presents to one who has studied it in the field as well as in the closet.

This polymorphism, which at first strikes us as singular, is quite common among plant-lice, and many curious instances of still more striking character might be given. Even the differences themselves, between gallæcola and radicicola are more apparent than real. Individuals of the latter are often met with, which, in the comparative obsoleteness of their tubercles, are almost undistinguishable from the former; and the tubercles, like many other purely dermal appurtenances, are of an evanescent and unimportant character. Many insect larvæ, which are normally granulated with papillæ, not unfrequently have these more or less obsolete, and at some stages of growth have the skin absolutely smooth. The same thing holds true of tubercles, which, as in the case of the Imported Currant-worm (Nematus ventricosus Klug), are often completely cast off at a moult. In Phylloxera they are very variable in size, as we shall see, in Rileyi; and in quercus, according to several reliable authors, the tubercles which are characteristic of the species in Southern France are entirely wanting around Paris. If we carefully study them in vastatrix we shall find that they consist of points where thrugosities, and becomes darker (Fig. 4, i). They do not e granulated skin is gathered around a fleshy hair in little occur in the newly-hatched larva, are not visible immediately after each moult, and are lost again in the winged individuals. In the form gallæcola we shall find, upon careful examination, especially of the exuvia, that, as Max-Cornu has shown, there are rows of these short hairs, scarcely extending beyond the natural granulations and corresponding to those on the tubercles of radicicola. These hairs are more visible on the younger and smoother lice, after the first moult; and they are sometimes so stout, particularly on the abdomen, as to remind one of those on Rileyi, to be described. The ventral characteristics of the two types are identical.

Since I proved, in 1870, the absolute identity of these two types by showing that the gall-lice become root-lice, the fact has been repeatedly substantiated by different observers. Yet, strange to say, no one has heretofore succeeded in making gall-lice of the young hatched on the roots, though I formerly supposed that Signoret had done so. It is, therefore, with much satisfaction that I record the fact of having succeeded this winter in obtaining galls on a young Clinton vine from young radicicola, and of thus establishing beyond peradventure the specific interrelation and identity of the two types. I make this announcement with all the more pleasure, that for three years past, both on vines growing out-doors and in pots in-doors, I had in vain attempted to obtain the same result.

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS.

The more Manifest and External Effects of the Phylloxera Disease.—The result which follows the puncture of the root-louse is an abnormal swelling, differing in form according to the particular part and texture of the root. These swellings, which are generally commenced at the tips of the rootlets, where there is excess of plasmatic and albuminous matter,[15] eventually rot, and the lice forsake them and betake themselves to fresh ones—the living tissue being necessary to the existence of this as of all plant-lice. The decay affects the parts adjacent to the swellings, and on the more fibrous roots cuts off the supply of sap to all parts beyond. As these last decompose, the lice congregate on the larger ones, until at last the root-system literally wastes away.

During the first year of attack there are scarcely any outward manifestations of disease, though the fibrous roots, if examined, will be found covered with nodosities, particularly in the latter part of the growing season. The disease is then in its incipient stage. The second year all these fibrous roots vanish, and the lice not only prevent the formation of new ones, but, as just stated, settle on the larger roots, which they injure by causing hypertrophy of the parts punctured, which also eventually become disorganized and rot. At this stage the outward symptoms of the disease first become manifest, in a sickly, yellowish appearance of the leaf and a reduced growth of cane. As the roots continue to decay, these symptoms become more acute, until by about the third year the vine dies. Such is the course of the malady on vines of the species vinifera when circumstances are favorable to the increase of the pest. When the vine is about dying it is generally impossible to discover the cause of the death, the lice, which had been so numerous the first and second years of invasion, having left for fresh pasturage.

Mode of Spreading.—The gall-lice can only spread by traveling, when newly hatched, from one vine to another; and, if this slow mode of progression were the only one which the species is capable of, the disease would be comparatively harmless. The root-lice, however, not only travel underground along the interlocking roots of adjacent vines, but crawl actively over the surface of the ground, or wing their way from vine to vine, and from vineyard to vineyard. Doubts have repeatedly been expressed by European writers as to the power of such a delicate and frail-winged fly to traverse the air to any great distance. "On a calm, clear day, the latter part of last June, it was my fortune to witness a closely-allied species (Phylloxera caryæfoliæ Fitch), of the same size and proportions, swarming on the wing to such an extent that to look against the sun revealed them as a myriad silver specula. They settled on my clothing by dozens, and any substance in the vicinity that was the least sticky was covered with them. With such a sight before one's eyes, and with full knowledge of the prolificacy of these lice, it required no effort to understand the fearful rapidity at which the Phylloxera disease has spread in France, or the epidemic nature it has assumed. Imagine such swarms, mostly composed of egg-bearing females, slowly drifting, or more rapidly blown, from vineyard to vineyard; imagine them settling upon the vines and depositing their eggs, which give birth to fecund females, whose progeny in five generations, and probably in a single season, may be numbered by billions, and you have a plague (should there be no conditions to prevent that increase) which, though almost invisible and easily unnoticed, may become as blasting as the plagues of Egypt."[16]

Since the above-quoted passage was written, I have fully proved the same ability to fly in the winged grape-root lice, and am satisfied that they can sustain flight for a considerable time under favorable conditions, and, with the assistance of the wind, they may be wafted to great distances. These winged females are much more numerous in the fall of the year than has been supposed by entomologists. Wherever they settle, the few eggs which each carries are sufficient to perpetuate the species, and thus spread the disease, which, in the fullest sense, may be called contagious. Whether in a state of nature these winged females show a preference for any one part of the vine in the consignment of their eggs, is not yet known. It is quite certain, however, that they do not reënter the ground. Neither do we know whether—in the light of Balbiani's discoveries regarding the European Oak Phylloxera—the young hatching from these eggs produce the diminutive sexual individuals already described. In confinement I have had such eggs deposited both on the leaves and on the buds, and from the preference which, in ovipositing, these aërial mothers showed for little balls of cotton placed in the corners of their cages, I infer that the more tomentose portions of the vine, such as the bud, or the base of a leaf-stem, furnish the most appropriate and desirable nidi. On this hypothesis it is quite possible for the insect to be introduced from vineyard to vineyard, or from country to country, as well upon cuttings as upon roots.

- ↑ "Annales de la Société Entomologique de France," tome iii., p. 222.

- ↑ "New York Entomological Reports," vol. i., p. 158.

- ↑ Report, vol. iii., § 117.

- ↑ Proceedings Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, January, 1867.

- ↑ Messager du Midi, July 22, 1868.

- ↑ "Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris," September 14, 1868.

- ↑ Gardeners' Chronicle, January 30, 1869.

- ↑ "Insectologie Agricole," 1869, p. 189.

- ↑ "Quadrupeds of North America," vol. i., p. 215.

- ↑ "Practical Entomologist," vol. i., p. 17.

- ↑ "Annales de la Société Entomologique de France," 1867, pp. 301, 308.

- ↑ "Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris," 1873, p. 884.

- ↑ Auctore Dr. Fr. Cazalis, as reported in the Messager du Midi, November 16, 1873.

- ↑ I have examined thousands in the vineyard in early spring, and other thousands reared artificially in a warm room in winter.

- ↑ For a very minute and careful study of the pathological characteristics of these swellings the reader may refer to Max-Cornu's excellent papers in the Comptes Rendus, for 1873, of the Paris Académie des Sciences.

- ↑ "Entomological Report of Missouri," vol. v., pp. 72, 73.