Popular Science Monthly/Volume 54/March 1899/The California Penal System

| THE CALIFORNIA PENAL SYSTEM. |

By CHARLES HOWARD SHINN.

THEORETICALLY every new commonwealth in organizing its institutions can measurably avoid the errors of older communities, and can venture upon promising experiments elsewhere untried. In practice, however, new States are usually compelled to face unforeseen difficulties, and although their various departments gain something in flexibility, they lose in systematic organization. They have the faults as well as the virtues of the pioneer.

Penology, like every other department of human thought, is a battlefield of opposing principles. But I know of nothing in print more inspiring to the officers of the State engaged in prison and reform work than Herbert Spencer's Essay on Prison Ethics. It is likely that many of the people who should read it are not aware of its value and interest to themselves. Beginning at the foundations, Mr. Spencer makes a lucid exposition of the necessity of "a perpetual readjustment of the compromise between the ideal and the practicable in social arrangements." As he points out, gigantic errors are always made when abstract ethics are ignored.

If society has the right of self-protection, it has, as Mr. Spencer asserts, the right to coerce a criminal. It has authority to demand restitution as far as possible, and to restrict the action of the offender as much as is needful to prevent further aggresssions. Beyond this point absolute morality countenances no restraint and no punishment. The criminal does not lose all his social rights, but only such portion of those rights as can not be left him without danger to the welfare of the community.

But absolute morality also requires that while living in durance the offender must continue to maintain himself. It is as much his business to earn his own living as it was before. All that he can rightfully ask of society is that he be given an opportunity to work, and to exchange the products of his labor for the necessaries of life. He has no right to eat the bread of idleness, and to still further tax the community against which he has committed an aggression. "On this self-maintenance equity sternly insists." If he is supported by the taxpayers the breach between himself and the true social order is indefinitely widened.

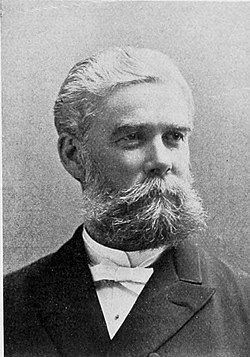

Such principles as these could easily have been made a fundamental part of the California prison system when the State was organized, for the famous Code of Reform and Prison Discipline, prepared about 1826 by a New Orleans lawyer, Edward Livingston, was well known to some of the ablest men of pioneer California, and a strong effort was made to obtain its adoption in complete form. That remarkable code known as the Livingston system agrees with the Spencerian principles of ethics, and has been a source of inspiration for the most advanced penal legislation of recent years. Louisiana adopted it only in part, but Belgium has the Livingston code in its entirety. California, suffering under difficult local conditions, took a course in the liberal pioneer days that has for a time rendered progress  Warden W. E. Hale, of San Quentin. along the lines of modern development extremely difficult.

Warden W. E. Hale, of San Quentin. along the lines of modern development extremely difficult.

California is a large and populous State, many portions of which are thinly settled and hard to reach. In early days it had many Spanish and Mexican outlaws, and became a refuge for criminals from all parts of the world. When the State was organized, money was extremely abundant, and every one had golden dreams. The idea of self-supporting prisons seemed absurd, not only because the rich young State seemed capable of supporting any expense, but also because no manufactures were yet established, and the most active penologist would have found it hard to find suitable employment for prisoners.

As time went on, the very strong labor unions of California, aided by many newspapers and politicians, accepted the principle that every dollar a convict earned was taken from some citizen, and that the State was bound to support its criminals in idleness. Numbers of good and earnest men in the service of the State as prison commissioners, wardens, and other officials studying methods elsewhere and mindful of local conditions, have made untiring efforts to stir the public conscience, and to gain recognition of a criminal's right to earn his own living by productive labor. As long ago as 1872 Hon. E. T. Crane, of Alameda County, chairman of a joint Assembly and Senate committee, made an excellent and progressive report on prison reforms. Something has been gained since then, and, though working under adverse conditions, the prisons have been excellently managed. But these results are due to individuals, not to the system, nor to the well-meant but often injurious enactments of legislatures meeting biennially for only sixty days.

Under the system of biennial State appropriations, nearly all institutions suffer at times from mistaken kindness, and at other times from undue parsimony. Since there is no general supervising board for the two State prisons and the two State reform schools, and no settled ratio of appropriation based upon the number of inmates, the friends of each institution naturally do their best to obtain as large appropriations as possible from each new legislature. Hence arise special visiting committees and combinations between legislators from different parts of the State to "take care of" institutions whose regular annual income should not be dependent in the least upon politics.

The appropriations made by the last two legislatures for all purposes connected with prisons and reform schools, including salaries of officials, are shown in the following table:

State Appropriations from July 1, 1895, to July 1, 1899 (Forty-seventh to Fiftieth Fiscal Years, inclusive).

| Name of Institution. | Sum granted. | Average yearly grants. |

| San Quentin Prison | $615,153.40 | $153,788.35 |

| Folsom Prison | 488,000.00 | 109,500.00 |

| Preston School of Industry | 237,000.00 | 59,250.00 |

| Whittier State School | 403,000.00 | 100,750.00 |

| Transportation of prisoners | 150,000.00 | 37,500.00 |

| Totals | $1,843,153.40 | $460,988.35 |

Some small appropriations for improvements are necessarily included in these totals, but nothing more than may be expected every year or two. It is proper to rate the average annual expense of these institutions at nearly half a million dollars, nor can this sum be materially reduced until the State accepts the fundamental principle that prisons should be made nearly or quite self-supporting.

San Quentin was once managed to some extent on the contract system. Furniture-makers and other manufacturers paid half a dollar a day for each convict employed, and at one time as many as eight hundred men were thus utilized, giving the prison an income of twenty-four hundred dollars a week. The system was so violently attacked by labor unions that it was finally abandoned, and now I am told that convict-made furniture, stoves, and other articles such as were formerly made at San Quentin are brought to California from Joliet, Illinois, and other places by the carload.

Having abandoned the contract system, the State decided to make jute bags, chiefly for grain, and to sell them as nearly as possible at cost direct to the consumers, so as to help the agricultural classes. Machinery costing $400,000 was obtained in England, and after many difficulties a factory was established at San Quentin. The price of raw material fluctuates greatly, and the mill has sometimes lost money, sometimes made a somewhat nominal profit. During the fiscal year ending June 30, 1891, for instance, 2,574,254 pounds of goods were manufactured at a total operating expense of $160,084.07, and were sold at a price which nominally gave $40,275.07 profit. But no sinking fund was allowed for, to cover wear and tear of machinery, nor did the operating expenses include even the maintenance of the convicts while at work. The following fiscal year the profit estimated in the same way was $39,293.18. During the fiscal year 1893-'94 the loss on the jute mill was $14,660.22; in 1894-'95 there was a profit of $6,670.56; and in 1895-'96 a loss of $12,288.45.

In five years, therefore, there was nominally a profit of about $60,000 in this department, but since neither interest, sinking fund, nor maintenance of the laborers is included among the expenses, the system can be looked upon only as a means of giving needed exercise to the prisoners and cheap grain sacks to the farmers. Financially it is a burden to the taxpayers. The old contract system had its drawbacks, but it at least afforded a profit, and gave convicts a chance of learning something about certain trades at which they could perhaps work when released; the jute mill not only offers no such opportunity, but is in other ways peculiarly unfit for modern prison requirements, since all operations in such mills can be stopped or delayed by the misbehavior of a few operatives. Far better are industries wherein small groups or individuals are engaged in various separate minor operations. Besides this, the sacks made by prison labor will probably have only local uses hereafter, because of a recent act of Parliament which is held to prevent wheat shipments in such sacks.

The Folsom Prison owns a magnificent water power and enormous quarries of granite. Between 1888 and 1894 convict labor amounting to 683,555 days were expended upon a dam, canal, and powerhouse, and over 2,000 horse power can already be used. About 250 horse power is now utilized by the prison for electric lights, ice manufacture, and other purposes. The quarries are being worked to some extent, and crushed rock for roads is sold at cost or nearly so. There is a farm that supplies many articles at less cost than if purchased in the market, At Folsom, as at San Quentin, the authorities do all in their power to economize, and to utilize convict labor, but the policy of the State prevents definite progress.

Meanwhile the reports of the prison directors and wardens and the messages of Governors have urged in the strongest terms a change. The biennial report of 1892-93 and 1893-94 says respecting the great Folsom water power: "If we can use this power solely with regard to profitable results to the State, we can return each year a surplus into the State treasury. We do not think that the State should refrain from working its convicts or utilizing its advantages because it may have some effect upon other businesses. All over the United States prisoners are engaged in manufacturing, and our investigations lead us to believe that the effect of prison competition, so called, is greatly overestimated."

The biennial report of 1894—'95 and 1895-'96 returns to the subject, states that the jute mills can not be a success under the restrictions

Folsom State Prison.

of the present law, and urges that they should be run on a business basis, for a profit. It continues, "One source of profit would be to make use of the granite owned by the State" (at Folsom). It suggests a consolidation of the two prisons at Folsom, where, with prison labor and free power, and granite on the ground, a model prison could be constructed. Warden Aull, of Folsom Prison, in discussing the subject in 1896, said that for nine years the improvements there have employed the convicts, but now some new scheme must be devised. "The convicts must be kept at work. Every consideration of discipline, economy, reformation, and health demands this." But he believes that it will not pay the State to make shoes, blankets, clothing, brooms, tinware, etc. (as has been suggested at various times) for the eight thousand inmates of our State institutions. There are over two thousand convicts at Folsom and San Quentin. Only a small part of these, he says, could be utilized in making goods for State institutions, nor would there be any profit unless manufacturing was on a large scale for the outside markets as well. The experiment that New York is making will be watched with much interest here.

The California labor unions recently adopted resolutions favoring "the quarrying of stone by convict labor, and the placing it upon market undressed at a low figure, in order to give employment to stone-cutters, stone-masons, and others employed on buildings." The State rock-crushing plant, if kept running, will utilize the labor of about two hundred and fifty convicts. Any advance beyond this point means open war with all the labor unions.

Evidently the time when the prisons of California are to be entirely self-supporting is still remote, and the public as well as the union need much more education upon the subject. Some reduction of expenses, together with any utilization of convict labor that indirectly benefits a few classes, is all that can be hoped for at present, but ultimately the reformation of the criminal by making him capable of self-support as well as anxious to live in peace with society, will be recognized as the aim of wise penal legislation.

There is no doubt but that many profitable industries can be found, as yet unnaturalized in California, and therefore coming only incidentally into competition with existing industries, but well adapted to prison labor. One of these industries is the growth and preparation of osier willows of many species, and their manufacture into many useful forms, especially into baskets for fruit pickers and for wine makers. Another possible industry is the growth and preparation of various semitropic species of grasses and fiber plants, from which hat materials, mattings, the baskets used in olive-oil manufacture and a multitude of other articles can be made. The sale of crushed rock at Folsom should, of course, be at a price which at least pays for the sustenance of the convicts employed. The enormous water power of the prison should ultimately be fully utilized for manufacturing purposes.

Let us now turn to a consideration more in detail of the separate prisons, and to a brighter side—that which concerns the men who are doing the best they can with a bad system. San Quentin, the oldest of the two, has been for six years under the wardenship of an able and attractive man, William E. Hale, formerly Sheriff of Alameda County. Those who have read the wonderfully interesting reports of the National Prison Convention are familiar with his methods and views. The report for 1895 (Denver meeting) shows that Warden Hale, in the breadth and sanity of his views, easily takes rank among the best wardens of the country. He thoroughly understands California and the Californians, and while progressive has never attempted the impossible. In his various reports and addresses he especially urges more industrial schools, better care of children, and more kindergartens, such as those established in San Francisco by the late Sarah B. Cooper. And, indeed, who can read Kate Douglas Wiggin's story of Patsy without recognizing the value of kindergartens in the prevention of crime? The San Francisco police once traced the careers of nine thousand kindergarten pupils, and found that not one had ever become a law-breaker.

Last summer San Quentin was the scene of an "epidemic of noise" on the part of many of its inmates. Some of the newspaper accounts of the affair were painfully exaggerated, and the prison management in consequence was severely criticised. The fact is that the outbreak was quelled rapidly and effectually, without outside help, with only a few days' interruption of work on the jute mill, and without injury to any person. A hose was simply turned into the noisy cells until their inmates were subdued.

There have been very few escapes in the history of the prison, and none in recent years. Its situation, on the extreme eastern end of a rocky peninsula of Marin County, projecting into the bay of San Francisco, is extremely well chosen for safety and isolation. The State owns a large tract here, but it is very poor soil, and much of its surface clay has been stripped for brick-making, so that no income from it is possible unless more bricks can be made and sold. The prison accommodations are extremely cramped, and large quantities of brick should be used in needed extensions. Many small industries could be carried on here, if permitted, for water carriage to and from San Francisco is very cheap. Heavy manufactures requiring expensive steam power are not justified here.

The abandonment of the large State improvements at San Quentin seems contrary to the dictates of economy. Equally unwise is the suggestion that it be made a prison to which only the most dangerous classes of criminals should be sent. On the other hand, Folsom, with its quarries and water power, seems fitted for a receiving prison, where all convicts, without exception, should be placed on indeterminate sentences at hard labor, and from which, on good behavior, on the credit system, they might be removed by the prison directors to San Quentin, there to work at more varied but no less self-supporting trades. The ponderous jute-mill machinery should all be transferred to Folsom, where power is now running to waste. At San Quentin, first, the State should adopt more advanced reformatory methods.

Official statistics of the two prisons contain many interesting features. In mere numbers the increase during the past two decades has not kept pace with the increase in the State's population. San Quentin at present usually contains about fourteen hundred and Folsom about nine hundred, but an increase equal to the gain in population would give them three thousand instead of twenty-three hundred. Even during the so-called hard times of recent years there has been no marked additions to the criminal classes in California, and the two great strikes—that of the ironworkers and that of the railroad brakemen and firemen—led to surprisingly few violations of the laws.

Close observers say that there has been a marked increase during the past decade in the number of tramps, and that petty criminals have increased everywhere. But there are no statistics of the county and township jails. It seems certain that many villages and small towns, even where incorporated, have increasing trouble with gangs of hoodlums who are rapidly fitting themselves for State prisons. The reform schools have been largely recruited from this semi-criminal element, but stronger laws, swifter punishment, more firmness in dealing with young offenders, and, in brief, a higher grade of public sentiment on the part of citizens of small towns is evidently necessary. According to recent discussions in the New York Evening Post, the same sort of thing occurs in staid New England, and there, as here, it is one of the most serious problems of the times. From such a class of idle and vicious boys the prisons will hereafter be recruited, rather than from newcomers.

The nativity tables of both prisons show that the number of California-born convicts ranges in recent years from eighteen per cent in 1890 to nearly twenty-five per cent in 1895-96. In that year in San Quentin, out of 819 American-born convicts, 314 were born in California, 68 in New York, 44 in Pennsylvania, 41 in Illinois, 36 in Ohio, and 35 each in Massachusetts and Missouri. Oregon sends 12, Arizona 10; Washington and Nevada are represented by only one apiece. The Southern States, excepting Kentucky and Virginia, send very few. Something the same proportion throughout holds at Folsom, and fairly indicates the States from which the population of California is chiefly drawn. The total of American nativity at San Quentin is sixty-four per cent; at Folsom, as last reported, it was about sixty-five per cent. Of the foreign born (thirty-six per cent at San Quentin), 99 out of 481 were Irish, 82 were Chinese, 56 were German, 49 were Mexican, and 44 were English. No one doubts that the laws are strictly enforced against the Chinese and the Mexicans (meaning Spanish-Californians); the other classes have votes and influence, and often have better chances for avoiding punishment for misdeeds. Japan contributes only one convict to San Quentin and two to Folsom. The Chinese as a rule go to prison for assaults upon each other ("highbinding"), for gambling, or similar offenses, but seldom for crimes against Americans. The Mexicans generally come to grief from an old-time penchant for other people's horses, or from drunken "cutting scrapes."

A racial classification attempted at Folsom showed that out of 905 convicts 704 were Caucasian, 89 Indian and Mexican, 62 Mongolian, and 50 negroid. I do not find this elsewhere, so it may stand alone as merely one year's observations.

Of much more importance are the statistics of illiteracy, kept for a term of years. Warden Hale reports in 1896 that out of 1,287 prisoners, 120 can neither read nor write, 220 can read but can not write, and 947 can both read and write. Of course, many who are rated in the third class read and write very poorly, and a careful classification in terms of the public-school system is essential to clearness. Warden Aull, at Folsom, reports that out of 905 convicts, 6 are college men, 81 are from private schools, 53 from both public and private schools, 582 have attended public schools only, and 147 are illiterate, while the remaining 36 call themselves "self-educated."

According to the evidence of the wardens, no full graduate of any American university has ever been an inmate of either prison. The so-called college men were men who had spent some time at a college of one kind or another. So-called professors appear among the convicts, but I have been unable to discover that any professor in an institution of standing has been at either San Quentin or Folsom since its establishment.

The preceding statistics of illiteracy are defective, but some additional light can be had from the tables upon occupations. Among 905 prisoners at Folsom, 96 occupations were represented. In round numbers, thirty-four per cent were mechanics, twenty-nine per cent were rated as laborers, twenty per cent were in business, and seven per cent were agriculturists. But a closer analysis of the statistics on this point shows that nearly fifty-seven per cent of the entire number came from the following occupations: acrobat, barber, bar-tender, butler, cook, gardener, hackman, hostler, laborer, laundryman, mill-hand, miner, nurse, sailor, vaquero, and "no occupation" (22).

The classification of crimes is very complete in all prison statistics, and usually follows the legal phraseology. Nearly all come under three great divisions—crimes against property, crimes of anger, and crimes which arise from a perverted sexuality. From year to year the proportion in these great divisions varies but little. In 1894 out of 1,287 convicts, 796 were sentenced for crimes against property, 358 of which were for burglary, 170 for grand larceny, and 39 for forgery; there were 343 commitments for assaults and murder, 188 of which were for murder in either the first or the second degree; lastly, there were 85 commitments for rape and other sex crimes. This was a typical year, and will serve to illustrate for all and at both prisons.

The terms of imprisonment are long: out of 1,300 men in one annual report, 143 were for life, and 392 for ten years or more. Over 300 prisoners had served more than one term, and some were even serving their eighth term. Some at Folsom have reached their twelfth term. The ages of the prisoners have ranged from sixteen to eighty-six, but the danger period is evidently between eighteen and forty.

All of the prison officers agree respecting the bad physical condition of the convicts. Many of them are weak and ill when they enter the prison; many are the victims of unnamable personal vices. The physicians at San Quentin in 1895 reported 27 cases of scrofula, 30 of syphilis, 22 of epilepsy, 29 of opium habit, 62 of rheumatism, 70 of typhus fever, and 124 of general debility. Medical statistics at Folsom show similar conditions, aggravated by the malarial climate of that locality. The death rate, formerly higher at Folsom than at San Quentin, is now considerably lower, owing to the much better accommodations for the prisoners, and the hard outdoor labor required. In 1896 it was but.79 of one per cent.

It is gratifying to observe that the cost of maintenance of the prisoners has been gradually reduced. Nearly thirty years ago legislative committees reported that the cost of running the State's prisons was four or five times as much in proportion to the inmates as that of any other State in the Union, and that the prisoners lived better than the average landowner. More economical methods were gradually adopted, and by 1891 the cost per diem of a convict was 40 cents. This has been still further reduced; at San Quentin to 30.45 cents, and at Folsom to 32.50 cents.

There will always be outside criticisms of the food supplied as "too good for convicts," but it is merely that of ordinary field laborers, with much less variety. Under California conditions it could not well be made cheaper. If the food statistics of the prisons were so compiled as to separate the butter, olives, raisins, canned fruit, etc., properly used on the tables of officers and wardens, from the articles purchased for the prisoners, much misapprehension would be prevented.

As long as the State pays the entire expense bill, however, there will be a natural restiveness on the part of the taxpayers; the prison management, no matter how careful it is, must suffer for the sins of the system. The present directors and wardens are intelligent and honest men, who could put the prisons on a self-supporting basis if they had the authority and the necessary means for the plant required. A comparatively small amount of manufactures would pay the daily maintenance of the prisoners, and thus render the management much less subject to public criticism.

This article is already as long as seems desirable, and I must close without describing the California reform schools, which are comparatively new, but have attracted much attention. At some future time I may have an opportunity to take up that subject.

| THE SCIENTIFIC EXPERT AND THE BERING SEA CONTROVERSY. |

By GEORGE A. CLARK.

IN the November number of the Popular Science Monthly for 1897, Dr. Thomas C. Mendenhall reviews at some length the workings of the Bering Sea Commission of 1892. Dr. Mendenhall was himself a member of this commission, and his account of its inside history is interesting and instructive as throwing light upon the after-work of the Paris Tribunal of Arbitration for which it was to prepare the natural-history data.

Dr. Mendenhall naturally finds little to commend in the work of his colleagues, the British experts, but he does not stop there, and proceeds to generalize in an uncomplimentary way regarding scientific experts as a class. For example, he lays down the following just and admirable rule for scientific investigation: “It should be commenced with no preconceived notions of how it is to come out, and judgment should wait upon facts,” and then continues to say: “Justice to the man of science obliges the admission that, take him in his laboratory or library, with no end in view except that of getting at the truth, and he generally lives fairly up to this high standard; but transform him by the magic of a handsome retainer, or any other incentive, into a scientific expert, and he is a horse of another color.”

It is not the purpose of this article to argue the cause of the man of science, or to say whether or not this arraignment is just. It is the intention merely to bring into contrast with the notable example of failure which Dr. Mendenhall cites, an equally notable example of success on the part of the scientific expert. If I mistake not, this simple comparison will be all the vindication the man of science needs.

To understand the full force of Dr. Mendenhall's article, it must be remembered that it appeared on the very eve of the meeting of a second Bering Sea Commission called to consider the selfsame issues which occupied the attention of the commission of 1892. The article therefore stands as a prediction of failure for the new commission.