Popular Science Monthly/Volume 63/May 1903/The Progress of Science

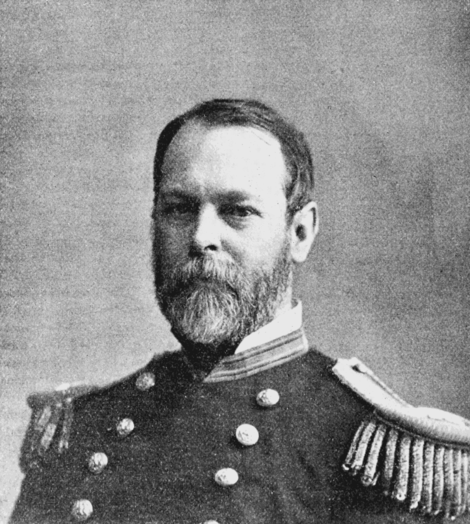

WILLIAM HARKNESS.

In the death of Professor William Harkness, U. S. N., America loses one of the group of scientific men who have given this country high rank in its contributions to astronomy. While Harkness may not have made brilliant discoveries, he accomplished a large amount of painstaking work, and had an important share in the

expeditions of the U. S. Naval Observatory and in arranging its equipment. He was born in Scotland in 1838, his father being a clergyman. He was educated at Lafayette College and Rochester University and studied medicine in New York City, being for a time surgeon during the civil war. He was appointed aid in the U. S. Naval Observatory in 1 802, and his connection with this institution continued for thirty-seven years until his retirement with the rank of rear-admiral in 1899). Harkness served on the monitor Monadnock in its cruise through the Straits of Magellan, making exhaustive observations on the behavior of compasses under the influence of iron armor and also terrestrial magnetic observations. This work was published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1871. He observed the total solar eclipse of 1869 at Des Moines and of 1870 in Sicily. Soon thereafter he devoted himself to the arrangements for the transits of Venus in 1874 and in 1882. The former transit he observed in Tasmania, later spending some years in reducing the observations, in the course of which he invented the spherometer caliper. He observed the transit of Mercury in Texas in 1878 and the total solar eclipse in Wyoming in the same year, and devoted much time to editing and preparing the reports. Professor Harkness then carried out an important work in reducing the observations of the zones of stars observed by Gilliss in Chili, and later prepared his work on the solar parallax and its related constants. From the publication of that work in 1891 to his retirement he was principally occupied with the new building of the observatory, in devising and mounting its instruments and in establishing a system of routine observations. Professor Harkness on his retirement expected to take only a few months' rest, and then to continue his scientific work at Washington, but he suffered from nervous prostration, and for the four years until his death he was scarcely able to leave his house.

THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF NATURALISTS.

Brief reference has already been made here to the meeting of the American Society of Naturalists held at Washington in convocation week in conjunction with the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and other scientific societies. The annual discussion before the society, the subject of which was 'How can endowments be used most effectively for scientific research,' has now been published. Professor Chamberlin, of the University of Chicago, who opened the discussion, spoke of the importance of endowing in connection with universities not only chairs and departments but also special schools and colleges of research. He said that instead of the colleges of the English universities, devoted mainly to personal education, the ideal university should be an association of colleges of research for the benefit of mankind as a whole. He also held that we need independent institutions of research and endowments for the coordination of research. Professor Welch, of the Johns Hopkins University, spoke with special reference to the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, describing what had been accomplished since its foundation two years ago, and foreshadowing the permanent institution, the establishment of which has since been announced. Professor Boas, of Columbia University, spoke with special reference to publications, arguing that academies and other institutions should unite their publications, so that series for each of the sciences might be established; the wasteful effects of competition and the exchange system of publication would then be supplanted by series that would became self-supporting. Professor Wheeler, of the University of Texas, criticized the present system of fellowships, and argued that fellows should be selected competent to carry on research, that they should not be regarded as recipients of alms, or required to waste their time on routine work, or do work beyond their power or in a place unsuited to it. Professor MacMillan, of the University of Minnesota, favored the multiplication of institutions and agencies for research. and said that there is some danger lest too great cooperation might lead to subordination. Professor Münsterberg, of Harvard University, argued that the equipment for research in America is ample, the difficulty is in the lack of the right men. Americans are particularly well suited to research work, but the ablest students tend to follow law or business, where the rewards are greater. Endowments can accomplish the most by creating great premiums, as by establishing an 'over-university,' where the masters of research chosen by their peers would be brought together for work transcending the possibilities under existing conditions. The giving of subsidies to individual men of science and to existing institutions is a system of charity that will in the end weaken research.

The address of the president. Professor Cattell, of Columbia University, was on the natural history of men of science. He gave the following table, showing the number of American men of science and their distribution among the sciences by different agencies:

| Special Societies. |

Fellows of Assoc- iation. |

Member of Academy. |

Univer- sity Prof- essors. |

Doctor- ates in Five Years. |

Contrib- utors to Science, 13 Vols. |

Who's Who. | Biog. Dictionary (estimated). | |

| Mathematics | 375 | 81 | 1 | 136 | 61 | 3 | 46 | 380 |

| Physics | 149 | 167 | 23 | 105 | 69 | 155 | 73 | 556 |

| Chemistry | 1933 | 174 | 12 | 143 | 137 | 73 | 166 | 656 |

| Astronomy | 125 | 40 | 12 | 41 | 16 | 48 | 51 | 212 |

| Geology | 256 | 121 | 13 | 55 | 32 | 161 | 174 | 436 |

| Botany | 169 | 120 | 7 | 57 | 53 | 94 | 70 | 416 |

| Zoology | 237 | 146 | 17 | 83 | 71 | 243 | 131 | 620 |

| Physiology | 96 | 10 | 2 | 53 | 18 | 22 | 25 | 156 |

| Anatomy | 136 | 10 | 0 | 56 | 1 | 13 | 18 | 116 |

| Pathology | 138 | 14 | 5 | 68 | 4 | 44 | 56 | 224 |

| Anthropology | 60 | 60 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 56 | 37 | 92 |

| Psychology | 127 | 40 | 1 | 37 | 63 | 58 | 21 | 136 |

| 3801 | 983 | 96 | 838 | 531 | 1002 | 868 | 4000 |

RACE SENESCENCE.

The article on 'The Decrease in the Size of American Families,' contributed by Professor Thorndike to the present number of the Monthly, is one of the first attempts to solve by scientific methods a scientific problem of the first magnitude. Incidental remarks by persons high in authority have led to numerous newspaper comments, serious and otherwise, on the failure of college graduates to reproduce themselves, and 'race suicide' has become a current term. The question of the decreasing birth rate has, however, for some years been a subject of discussion by French economists, and it has been recognized that the conditions in New England are similar. Indeed, nearly every country shows a decreasing birth rate, though only France and New England have a native population that is actually decreasing, destined, if present conditions continue, to be exterminated.

Attention has been attracted to the subject in France by economic conditions—the failure to maintain a population equal to that of Germany and Great Britain, the lack of young men for the army and the like—and economic and social causes have been assigned for the small families. The chief cause is said to be the method of dividing property among the children. The French peasant is a landowner, and if his property is to be maintained intact, he must have but one son, and can not afford to give the necessary dot to more than one daughter Other causes are also alleged—the increase of luxury, high taxation, the crowding into cities, immorality, alcoholism, etc. It is nearly always assumed that the families are small because the parents wish to have them small, and the remedies proposed, such as exemption from taxation or the payment of bounties in the case of larger families, are based on this supposition. But facts are lacking. For example, if voluntary restraint due to the economic conditions usually alleged is the cause, and the French family wishes to have one son and not more, then when there is but a single child (as is the case in one fourth of all families), it would be more often a boy than a girl; the most common family of two would be a daughter and a younger son and the most common family of three would be two daughters and a younger son. Apparently no such statistics have been collected or even proposed.

The alleged causes of the small families in France do not seem to obtain in New England. It is extremely improbable that all parents should voluntarily limit the size of families; the decreasing family must be in part due to physiological causes, which may be individual or racial. Individual causes may be late marriage, especially of women, school life and other unhygienic conditions, or an inhibition exerted by intellectual and other interests outside the family.

Racial sterility is certainly possible. It seems to conflict with the principle of natural selection, as fertility might be supposed to have a high selective value. Natural selection, however, can only select, it can not produce variations. If size of head is more variable than size of pelvis and is equally important for survival, the increasing difficulties of childbearing are not inexplicable on the theory of natural selection. If sterility increases, we must assume that the conditions of the environment have altered too rapidly for variation and natural selection to keep pace with them. Indeed the existing conditions may be due in part to our interference with natural selection. The decreasing death rate on which we pride ourselves may in part be responsible for the decreasing birth rate. When children who can not be born naturally or can not be nursed survive, we may be producing a sterile race. No statistics in regard to miscarriages are at hand, but there is good reason to believe that they increase as the number of children decreases. There is no positive proof of race senescence in man. On the contrary we know that the Italians and the French Canadians have large families, though there is as much reason for them to suffer from racial exhaustion as the inhabitants of France, and the Chinese seem to be in no danger of extermination. But we know that animals bred for special traits tend to become infertile, and selection for our civilization may have the same result. Physicists tell us that the earth may be uninhabitable in twenty million years; it may be uninhabited by man in twenty centuries.

THE FIELD COLUMBIAN MUSEUM.

The Field Columbian Museum, of Chicago, has now been in existence for ten years and has during this period made important progress. It was organized in 1893 at the close of the exposition, from which it received its building and some of its collections. The following year the name 'Field Columbian Museum' was adopted, owing to the generous gifts made by Mr. Marshall Field. The building erected for temporary purposes is gradually falling to pieces, and it is said that Mr. Field will provide a new building, which will surpass that of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and the new building for the U. S. National Museum, for which congress has recently appropriated three and a half million dollars. The report of the director of the Field Columbian Museum for last year describes important increases in the collections and improvements in their arrangement. The collections have been largely secured through sixteen expeditions sent to different parts of North America. Ethnology seems to have been specially favored, nine expeditions under the charge of Dr. George A. Dorsey and other members of the staff having made extensive collections in Oklahoma, New Mexico, Montana, California and Alaska. Two collections were also purchased, one of which contains fourteen hundred specimens from the Tlingits of Alaska. In the department of botany the herbarium has been augmented by over twenty thousand sheets, and the department of ornithology has been increased by fifteen hundred bird skins, obtained by Mr. Brenninger, largely in New Mexico, while numerous zoological specimens were obtained by Mr. Heller on the Pacific coast. Additions have also been made to the department of geology and in other directions.

Much attention has been paid to the cataloguing and exhibition of specimens, some thirty thousand entries having been made during the year, and some hundred thousand cards written, The sum of $26,000 has been spent on new cases, and many of the collections have been rearranged and new groups have been mounted by the taxidermists. We reproduce illustrations of two of these groups prepared by Mr. Akeley. The museum has been fortunate in adding to its scientific staff Dr. S. W. Williston, the well-known paleontologist, who shares his time between the museum and the University of Chicago. The attendance during the year was 262,570, a daily average of 719. This is an increase in attendance over the preceding year of 14,000, including 2.000, in paid admissions. The museum also conducted series of well attended lecture courses and published seven additions to its scientific series.

THE TREATMENT OF TYPHOID FEVER.

The London Times gives an account of a paper by Dr. Macfadyen, of the Jenner Institute, communicated on March 12 by Lord Lister to the Royal Society, which as the writer says is of peculiar interest to the public because it promises an efficient prophylactic and curative treatment for typhoid fever. That dreaded disease is known to depend upon the growth and propagation within the human body of the typhoid bacillus. Dr. Macfadyen has found that by crushing the microscopic cells of that bacillus, in a manner to be presently explained, the intracellular juices can be obtained apart from the living organism, and that these juices are highly toxic. By injecting them in small and repeated doses into a living animal its blood serum is rendered powerfully antitoxic and bactericidal. That is to say, it becomes an antidote alike to the living typhoid bacteria and to the poison which may be extracted from them. Animals dosed with the protective serum and subsequently treated with lethal doses of typhoid bacteria were found to enjoy immunity from typhoid fever, while others exposed to the same infection without the previous protective treatment died of the disease. In the same way animals receiving injections of the intracellular poison without any living bacteria escaped death only when previously treated with the protective blood serum of an animal which had gone through the immunizing process. Therefore the blood serum in question is a prophylactic for typhoid fever (at least, among the inferior animals). But further experiments were made by injecting lethal doses of the poison or of the living bacteria, and subsequently injecting the protective serum after half the time required for the toxic dose to kill the animal had been allowed to elapse. In these cases the antidote overtook the poison and the animals recovered. Therefore the serum is curative of typhoid fever when already established, as well as protective against typhoid infection. It is thus demonstrated that by the careful inoculation of an animal with the juices of the dead bacteria, its blood serum can, in the case of typhoid fever, be endowed with the antidotal properties hitherto developed, as in the case of diphtheria, only by inoculation with the living bacteria. It is reasonable to suppose that what holds good in the case of one pathogenic bacterium will also hold good in the case of others. But hypothesis, however reasonable, must be verified by experiment, and the work of extracting and investigating the juices of other bacteria is now being carried on at the Jenner Institute. Should it turn out, as may be expected, that bacterial juices in general react upon the animal organism in the same way as the living bacteria which produce them, the fact can not but have a profound influence upon medical speculation and practise.

The practical advantages of the discovery are great. When, in order to obtain a protective serum, an animal is inoculated with living pathogenic bacteria, the result is always quantitatively uncertain. The seed may fall upon a highly receptive and fertile soil, and may develop effects of unexpected violence, or it may fall upon an unusually sterile soil and fail to produce the expected results. In other words, we can not tell what will be the output of bacterial poison from a given dose of living bacteria. But the bacterial poison itself, when isolated from the living bacteria, is a definite pathogenic agent, which we can measure, dilute, and test like any other potent drug. Those who know that bacteria are so minute as to be invisible except under high microscopic powers will naturally ask by what unimaginable accuracy of grinding they can be broken up so as to release their intracellular toxins. The answer shows once more how close is the dependence of advance in one department of research upon discovery in another department apparently quite unrelated, and how impossible it is to foretell in what ways abstract inquiry may bear upon the most important practical problems. These infinitesimal organisms are crushed in liquid air, which is at once an absolutely neutral fluid and one giving the exceedingly low temperature essential for success. Thus an important step in the treatment of disease becomes possible through the previous success of efforts to reduce the most refractory gases to the liquid condition. The intense cold of liquid air has no effect upon the vitality of bacteria. After the most prolonged immersion they propagate themselves with unabated vigor as soon as they are again placed in normal conditions. But when frozen hard in liquid air these almost inconceivably minute cells are completely broken up by trituration. The completely triturated mass may be placed in the proper medium and raised to the proper temperature, but there is no sign of bacterial growth. The poisonous juices, however, remain and possess, as has just been demonstrated, the same toxic properties as when they are directly elaborated inside the human body by the living bacteria. We have, in fact, the best guarantee that nothing has happened beyond their mechanical release in the fact that at j the temperature of liquid air all chemical activities are in abeyance. The mechanical disintegration of these microscopical cells at the temperature of liquid air is not so simple a matter as it may seem. For its explanation the biologist must again apply to the physicist who has furnished him with this new and potent implement.

THE BRITISH ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION.

Reuter's Agency has cabled information from New Zealand reporting that the Morning, relief vessel to the British Antarctic exploration ship Discovery, arrived at Lyttelton on March 25. She reports finding the Discovery on January 23 in MacMurdo Bay (Victoria Land).

Commander Scott, of the Discovery, supplies the following report of the voyage up to the meeting with the Morning. The Discovery entered the ice pack on January 2 or 3 in latitude 67° south. Cape Adare was reached on January 9, but from there a heavy gale and ice delayed the expedition, which did not reach Wood Bay till January 18. A landing was effected on the 20th in an excellent harbor situated in latitude 76° 30′ south. A record of the voyage was deposited at Cape Crozier on the twenty-second. The Discovery then proceeded along the Barrier, within a few cables' length, examining the edge and making repeated soundings. In longitude 165° the Barrier altered its character and trended northwards. Sounding here showed that the Discovery was in shallow water. From the edge of the Barrier high snow slopes rose to an extensive, heavily glaciated land, with occasional bare precipitous peaks. The expedition followed the coast line as far as latitude 76°, longitude 152° 30′. The heavy pack formation of the young ice caused the expedition to seek winter quarters in Victoria Land.

On February 3, the Discovery entered an inlet in the Barrier in longitude 174°. A balloon was sent up. and a sledge party examined the land as far as latitude 78° 50′. Near Mounts Erebus and Terror, at the southern extremity of an island, excellent winter quarters were found. The expedition next observed the coast of Victoria Land, extending as far as a conspicuous cape in latitude 78° 50'. It was found that mountains do not exist here, and the statement that they were to be found is clearly a matter for explanation. Huts for living and for making magnetic observations were erected, and the expedition prepared for wintering. The weather was boisterous, but a reconnaissance of sledge parties was sent out, during which the seaman Vince lost his life, the remainder of the party narrowly escaping a similar fate. The ship was frozen in on March 24. The expedition passed a comfortable winter in well sheltered quarters. The lowest recorded temperature was 62° below zero. The sledging commenced on September 2, parties being sent out in all directions. Lieutenant Royds, Mr. Skelton, and party successfully established a record in an expedition to Mount Terror, traveling over the Barrier under severe sleighing conditions, with a temperature of 58° below zero.

Commander Scott, Dr. Wilson and Lieutenant Shackleton traveled 94 miles to the south, reaching land in latitude 80° 17′ south, longitude 163° west, and establishing a world's record for the furthest point south. The journey was accomplished in most trying conditions. The dogs all died, and the three men had to drag the sledges back to the ship. Lieutenant Shackleton almost died from exposure, but is now quite recovered. The party found that ranges of high mountains continue through Victoria Land. At the meridian of 160° foothills much resembling the Admiralty Range were discovered.

The ice barrier is presumably afloat. It continues horizontal, and is slowly fed from the land ice. Mountains ten or twelve thousand feet high were seen in latitude 82° south, the coast line continuing at least as far as 83° 20′ nearly due south. A party ascending a glacier on the mainland found a new range of mountains. At a height of 0,000 feet a level plain was reached unbroken to the west as far as the horizon. The scientific work of the expedition includes a rich collection of marine fauna, of which a large proportion are new species. Sea and magnetic observations were taken, as well as seismographic records and pendulum observations. A large collection of skins and skeletons of southern seals and seabirds has been made. A number of excellent photographs have been taken, and careful meteorological observations were secured. Extensive quartz and grit accumulations were found horizontally bedded in volcanic rocks. Lava flows were found in the frequently recurring plutonic rock which forms the basement of the mountains. Before the arrival of the Morning the Discovery had experienced some privation, as part of the supplies had gone bad. This accounted for the death of all the dogs. She has, however, revictualled from the Morning, and the explorers are now in a position to spend a comfortable winter.

THE NEW YORK FOREST AND GAME COMMISSION.

The eighth annual report of the Forest, Fish and Game Commission of New York state, recently submitted to the legislature, shows that commendable work has been accomplished during the past year. At the beginning of the year the Adirondack reserve contained 1,325,851 acres and the Catskill reserve 82,330 acres, and to these were added 28,505 acres last year. In the Adirondack Park there are also about 700,000 acres of private reserves and over 1,300,000 acres owned by individuals or companies. Of these lands about 1,000,000 acres are forest, about 700,000 acres lumbered, 48,000 waste, 43,000 burned, 48.000 denuded, 22,000 wild meadows, 100,000 improved and 125,000 water. During the last year reforestation was undertaken on a tract of 700 acres, the seedlings being

obtained from the nurseries of the State College of Forestry. Illustrations are given showing the state of the land before reforestation. The total expenses were $2,500 or less than one half a cent a plant. Owing to the organization of fire wardens, the loss from forest fires is greatly decreasing, It amounted last year only to $9,000, whereas in the neighboring state of New Jersey it was $108,000 and for the United States some twenty-five million dollars. It is estimated that nearly 200,000 people visited the Adirondack region last year for recreation and health.

A report is made on chestnut groves and orchards, which is not, however, very favorable to this industry. It appears that orchards in Pennsylvania have not been very successful, though groves of chestnut trees on waste mountain land may yield profitable results. A few elk and moose have been placed in the reserves, and it is believed that these animals will thrive. Pheasants have been distributed as usual and a large number of fish fry with some adults. An account is given of the shell fish industry. A hygienic examination has been made showing that the beds in Long Island Sound are removed from any possible contamination by sewage or otherwise.

SCIENTIFIC ITEMS.

Professor Henry Barker Hill, director of the Chemical Laboratory of Harvard College, died on April 6, in his fifty-fourth year. We regret also to record the death of Rear-Admiral George E. Belknap, retired, who, in addition to eminent services in the navy, was in charge of important hydrographic work and was at one time superintendent of the Naval Observatory; of Dr. Julius Victor Carus, associate professor of comparative zoology at Leipzig; of Dr. Franz Studnicka, professor of mathematics at Prague; of Dr. Laborde, an eminent French physician; and of Professor J. G. Wiborgh, of the Stockholm School of Mines, an authority on the metallurgy of iron.

Dr. Robert Koch has been elected foreign associate of the Paris Academy j of Sciences, in succession to Rudolf Virchow. Dr. Koch received twenty-six votes, Dr. Alexander Agassiz eighteen votes, Dr. S. P. Langley six votes and Professor van der Waals, of Amsterdam, one vote.—The Institute of France has awarded to Dr. Emile Roux, the subdirector of the Pasteur Institute, the prize of $20,000, founded by M. Daniel Osiris, for the person that the institute considered the most worthy to be thus rewarded. Dr. Roux will give the money to the Pasteur Institute.—A committee has been formed in Paris with M. H. Moissan as chairman to strike a medal in honor of the late M. P. P. Dehérain, formerly professor of plant physiology in the University of Paris.—Mr. Joseph Larmor, fellow of St. John's College, Cambridge University, has been elected Lucasian professor of mathematics in succession to the late Sir George Gabriel Stokes.—The subject of the Silliman lectures to be given at Yale University by Professor J. J. Thomson, of Cambridge University, will be 'Present Development of Our Ideas of Electricity.' The lectures, eight in number, will begin May 14.

President Roosevelt has appointed the following as a commission to report to him on the organization, needs, and present condition of government work, with a view to including under the Department of Commerce. bureaus not assigned to that department by congress: Charles D. Walcott, Department of the Interior; Brigadier-General William Crozier, War Department; Rear-Admiral Francis T. Bowles, Navy Department; Gifford Pinchot, Department of Agriculture; James R. Garfield, Department of Commerce and Labor.—Recently the President asked the Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries to have made a comprehensive and thorough investigation of the salmon fisheries of Alaska, and for this purpose Commissioner Bowers has appointed a special Alaska Salmon Commission consisting of the following: President David Starr Jordan, of Stanford University, executive head; Dr. Barton Warren Evermann, ichthyologist of the U. S. Fish Commission; Lieutenant Franklin Swift, U. S. N., commanding officer of the Albatross: Cloudsley Rutter, naturalist of the Albatross: A. B. Alexander, fishery expert of the Albatross: and J. Nelson Wisner, superintendent of fish cultural stations of the U. S. Fish Commission.

The council of the British Association for the Advancement of Science has nominated the Right Hon. Arthur James Balfour to the office of president for the Cambridge meeting in 1904. They further agreed to recommend to the association the acceptance of the invitation to South Africa for the year 1905.

The American Philosophical Society held at Philadelphia a general meeting on April 2, 3 and 4. Numerous papers were presented, including an address on the early work of the society by Dr. Edgar F. Smith, the president, and one on 'The Carnegie Institution during the first year of its development,' by President Daniel C. Oilman. The sessions were held in the hall of the society. Luncheon was served to members on each day; there was a reception to members and ladies accompanying them on Thursday evening, and visiting members were the guests of resident members at dinner on Friday evening.—The annual stated session of the National Academy of Sciences began at Washington on April 21.—The spring meeting of the council of the American Association for the Advancement of Science was held at Washington on April 23.

The administrative board appointed to organize and conduct the international congresses to be held in connection with the World's Fair in St. Louis in 1904, met on March 11 at the New York offices of the exhibition. There were present President Butler, of Columbia University, chairman; President Harper, University of Chicago; President Jesse, University of Missouri; Dr. Herbert Putnam, Librarian of Congress, and Frederick W. Holls, member of The Hague Tribunal. The board met to consider the report of the committee on the Congress of Arts and Science, which had been in session the two preceding days. The members of the committee met with the board. They are: Professor Simon Newcomb, Washington, chairman; Professor Hugo Münsterberg, Harvard University, and Professor Albion W. Small, University of Chicago. Mr. Howard J. Rogers, director of congresses, was also present. There is to be a 'Congress of Arts and Science,' with 128 sections. The board adjourned to meet in St. Louis on April 29.—The Swedish government has appropriated $20,000 for the publication of the scientific results of Dr. Sven Hedin s journey through central Asia. The work will comprise an atlas of two large volumes, while a third volume will contain Dr. Hedin's report on the geography of the country. Further volumes will be devoted to the meteorological observations, the astronomical observations, the geological, botanical and zoological collections, and the Chinese manuscripts and inscriptions. The work will be published in the English language.