Popular Science Monthly/Volume 65/October 1904/The Progress of Science

THE CAMBRIDGE MEETING OF THE BRITISH ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE.

The meeting of the British Association at Cambridge was an event of sufficient scientific importance to deserve attention here as well as in Great Britain. We are pleased, therefore, to be able to devote the present number of the Monthly to it. President Pritchett, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, contributes an interesting account of the general features of the meeting. The address of the president of the association and of the president of the section of mathematics and physics are printed in full, and parts of other addresses are given. These addresses appear to give the best available survey of the range and problems of modern science. It is possible that some of them are in part too technical for the purposes of the general scientific reader, but he must meet the man of science half way. The difficulty is more in the terminology than in the ideas. When the pages are scattered over with statoliths and gametes there is a natural tendency to skip rather than to add to our usable vocabulary. But the entire terminology needed to understand the main results of modern science is not more difficult than one foreign language and not more extensive than that of the sporting field. The language of science should be acquired by people of intelligence, but at the same time men of science should learn on occasion to address those who are not specialists.

In addition to the presidential addresses before the sections, the British Association makes arrangements for several still more popular lectures, one addressed explicitly to 'working-men.'

This lecture was given by Dr. J. E. Marr, of Cambridge, his subject being the 'Forms of Mountains.' Other lectures were given on 'Ripple Marks and Sand Dunes,' by Professor George Darwin; on 'The Origin and Growth of Cambridge University,' by Mr. J. W. Clark, and on 'Recent Paleontological Exploration,' by Professor H. F. Osborn, of Columbia University. On the other hand, the papers before the sections were mostly technical in character, though geography, anthropology, political science and education always give occasion for popular papers and discussions.

The entertainments and excursions at meetings of the British Association are always well arranged; it has indeed been urged that they are too attractive to camp followers. The social conditions in Great Britain are favorable to dinners and garden parties, and there is nearly always a duke or at least a lord ready to offer hospitalities. At Cambridge the entertainments were naturally academic in character, the principal functions being at Trinity and St. John's Colleges. Honorary degrees were conferred on some fifteen of the visitors, America being represented by Professor Osborn.

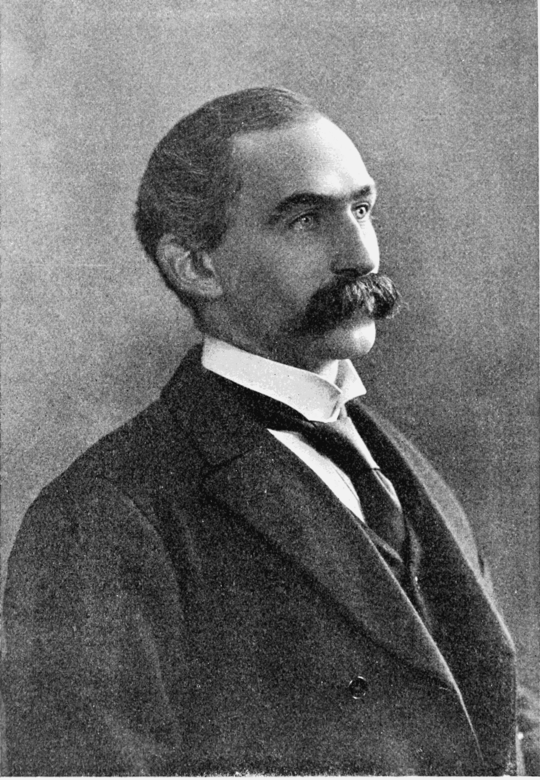

Cambridge proved to be an attractive place for the meeting, and no wonder, for a large part of the active British scientific workers have studied there, and the university unites scientific preeminence and medieval charm. The registration was 2,783, the sixth largest in the history of the association, and representing probably the largest gathering of scientific men. At Manchester and Liverpool, where the largest meetings have been held, the registration is swollen by local associates who pay the fees without taking Horace Lamb, LL.D., F.R.S.

Professor of Pure Mathematics, Owen's College, Manchester. President of the Mathematical and Physical Section.

THE ADDRESS OF THE PRESIDENT.

It is as long as forty-two years since the association last met at Cambridge. There was a meeting at Oxford ten years ago after an interval of thirtyfour years. The association was organized at York, in 1831, and held its second meeting at Oxford and its third meeting at Cambridge. It met again at Oxford in 1847 and 1860 and at Cambridge in 1845 and 1862. Some of the more conservative elements at the great universities have apparently not altogether welcomed the influx of visitors brought together by the diverse attractions of a meeting of the association. But if the meetings at the seats of the universities have not been frequent, they have tended to be of rather more than usual interest. The very contrast between the conservative and somewhat aristocratic attitude of the universities and the more radical and democratic aspects of the association have given an element of dramatic interest. Thus the Oxford meeting of 1860 is remembered for the invasion of the Darwinian theory. Bishop Wilberforce had been attacking the then infant theory in a superficial and rhetorical manner and is alleged to have turned to Huxley and asked him whether it was through his grandfather or his grandmother that he claimed his descent from a monkey. Huxley, after stating the case for evolution, said that a man has no reason to be ashamed (if having descended from an ape, but that he would be ashamed to be related to a man who used his ability and position to obscure the truth. No wonder that it was thirty-four years before the association was again invited to meet at the home of 'lost causes and impossible loyalties,' nor is it surprising that it should then have been presided over by a great statesman, who once more attempted to discredit evolution and the Darwinian theory.

Now after ten years the association meets at the sister university, and is presided over by the nephew and successor as head of the British government of the president of the Oxford meeting. It is a strange sight as

viewed from this land of magnificent levels. Mr. Balfour has character and abilities as notable and an intellect even more acute than had Lord Salisbury; there is a curious similarity in the attitude of the two men toward science, but at the same time an obvious forward movement in the authority of science when we pass from Oxford to Cambridge, from the older to the younger generation.

Lord Salisbury told his audience bluntly that he would make a survey 'not of our science but of our ignorance' and instanced atoms, the ether and the origin of life. He rejected natural selection and ended by appealing to the intelligent and benevolent, design of an everlasting creator and ruler. Mr. Balfour is too acute a thinker to set natural selection and design in opposition to one another. He, indeed, takes natural selection for granted and uses it to discredit the possibility of knowledge. He tells us that natural selection working through utility could only give us the senses needed 'to fight, to eat and to bring up children,' not the intellect required to understand physical reality. The more successful we are in explaining the origin of our beliefs 'the more doubt we cast on their validity.' Mr. Balfour, however, is ready to sanction the newest theories of physical metaphysics, saying that down to five years ago 'our race has. without exception, lived and died in a world of illusions'; now apparently Mr. Balfour and a handful of physicists live in a real world of ether and electrical monads. But perhaps Mr. Balfour is a hit ironical, and is The Hon. Charles Parsons, F.R.S.

President of Engineering Section.

Sydney Young, F.R.S.

Professor of Chemistry. Trinity College, Dublin. President of the Chemical Section.

only poking fun at simple scientific folks. The outcome of the two addresses, clearly indicated in the one subtly implied in the other, is that our science having failed, we might as well accept the doctrines of the established church.

Mr. Balfour's address will be read with interest by all. The more difficult but very able address of Professor Lamb, also published in this number of The Popular Science Monthly, should, however, be read in connection with it. As Professor Lamb tells us, science is justified by its results; we trust it because it honors our checks.

THE WORK OF THE SECTIONS.

The British Association is divided into ten sections, which are at times subdivided. There were for example this year subsections for cosmical physics and for agriculture. The range of the British Association is somewhat wider than that of the American Association. Our association has recently established a section for experimental medicine, but this has not been active, whereas physiology at the British Association has one of the best sectional programs. We have no section for education and our section for political and social science is not very strong. These two sections are likely to offer papers and discussions that are only on the edge of science, but with the sections of geography and anthropology they give suitable entertainment to the 'general hearer,' whose cooperation in scientific work it should be one of the objects of such an association to secure.

The most interesting part of the program of Section A, and perhaps the most important discussion of the meeting from the scientific point of view, was that on the radio-activity of ordinary matter, in which Professor J. J. Thomson, Lord Kelvin, Lord Rayleigh and Sir Oliver Lodge took part, four physicists whose work can scarcely be paralleled in any other country. Professor Thomson, to whom the new theories in regard to matter are so largely due. described work that had been carried on in his laboratory. It has been found that metals give out radiations peculiar to each metal. This can scarcely be due to the presence of a small quantity of radium as it is constant with different samples of the same metal. Sir Oliver Lodge remarked that on the electric theory of matter all matter ought to be radioactive, and no atom of matter should he regarded as absolutely permanent. Perhaps it would not be going too far to say that the burden of proof rested with those who denied that ordinary matter was radio-active.

Physics is undoubtedly stronger in Great Britain than in the United States, and the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge has through the discoveries of Maxwell, Rayleigh and Thomson become the chief center for physical investigation in the world. It is natural, therefore, that this science should have been well represented at the recent meeting. Dr. Glazebrook, director of the National Physical Laboratory, described its work. He told of the part taken by the British Association in its establishment, described the scientific and technical work in progress and concluded by pleading for a larger measure of support. A table was submitted showing the amount of expenditure on buildings and equipment, and of the annual grant allowed for maintenance in similar institutions in various countries; this clearly demonstrated the unfortunate position in which the laboratory was placed, while the number of tests made and the receipts from applicants contrasted favorably with those of other nationalities.

Among other contributions of special interest was a paper by Professor J. A. Fleming on the propagation of electric waves along spiral wires and on an appliance for measuring the length of waves used in wireless telegraphy, Aubrey Strahan, F.R.S.

District Geologist, Geological Survey of the United Kingdom. President of the Geological Section.

and an address by Professor J. H. Poynting on 'Radiation in the solar system.' A number of papers were presented to the section by foreign visitors including two by Professor Wood, of the Johns Hopkins University, one describing some recent improvements in the diffraction process of color photography and another on the anomalous dispersion of sodium vapor. Section A includes mathematics and astronomy as well as physics. Among the papers was one by Sir David Gill, director of the observatory at the Cape of Good Hope, entitled 'Problems of Astronomy.' which discussed some of the questions in practical astronomy now pressing for solution.

Before the Chemical Section Sir James Dewar gave an address on very low temperature phenomena with interesting demonstrations. He showed by a series of beautiful vacuum-tube experiments the behavior of nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen and argon when submitted in contact with charcoal to the cooling influence of liquid air. The nitrogen tube exhibited the usual violet color when the spark passed through it, but as soon as the charcoal was immersed in the liquid air the tube passed through various stages of attenuated brilliancy until ultimately the vacuum became so high that the current could scarcely overcome the resistance. When the liquid air was removed the changes were passed through in the reverse order. Oxygen passed through a similar series of changes, but in the case of hydrogen the absorptive power of the charcoal at the temperature of liquid air was not great enough to render the tube non-conductive. Lord Kelvin, in proposing a vote of thanks to Professor Dewar, said that he was filled with expectation as to the condition of things that would be disclosed at a temperature of 5° absolute, where there would be 110 motion. What would become of electric conductivity, of magnetism, of thermal conductivity? He wished Sir James would continue his electroconduct ivity experiments and bring him copper highly conductive at 8° but as great an insulator as glass at one or two or three degrees. Sir William Ramsay, speaking on the changes produced by the β-rays, said that he had obtained 105 milligrams of radium bromide, which, being too precious to risk in one vessel, were divided amongst three bulbs. These bulbs were placed in glass vessels, and were each provided with a tube to take away emanations. The vessels were colorless to start with, and were some of potash and some of soda glass, but in course of time the former became brown and the latter violet in color. The glass, too, became radio-active, but this property was removed by washing with water, although the color remained. When a solution of radium bromide was evaporated an invisible residue was left which was radio-active and dissolved to a radio-active solution. Radium formed chloride, sulphide, hydroxide and sulphate similar to lead, except that they were radio-active. The radium emanations rendered silver and platinum as well as glass radioactive. Professor W. O. Atwater, of Wesleyan University, presented two papers, one on the agricultural experimental work in the Smithsonian Institution and one on the experiments in nutrition carried out under his direction.

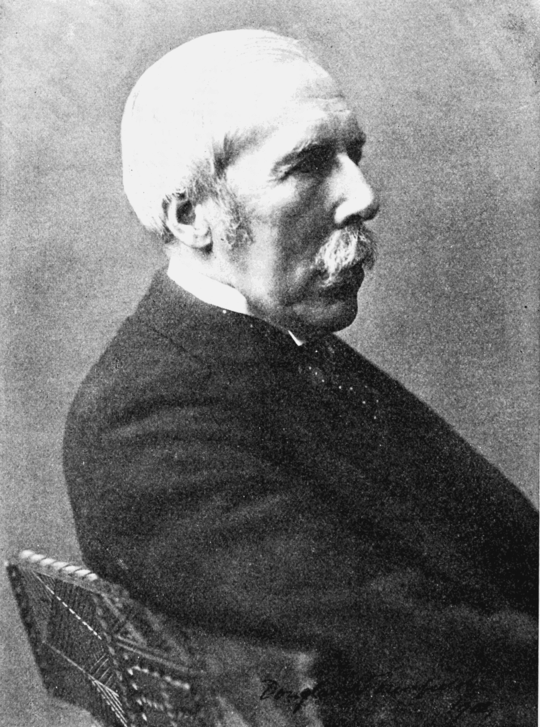

Mr. Aubrey Strahan's presidential address before the geological section was on earth movements, and this was taken as a subject for special discussion. In opening it Mr. Straham said that the subject proposed for discussion was the nature and origin of those movements of the earth's crust which have manifested themselves in the factoring, overthrusting and folding of strata. These movements have been in operation from the earliest to the latest geological periods; and, though they have been intermittent so far as anyone region is concerned, there is reason to believe that they have been more or Henry Balfour, M.A.

President of the Anthropological Section.

less continuously in action throughout the world as a whole. Their operations, in fact, arc essential to the existence of a land surface, for in their absence all rocks projecting above the sea would be worn away, and the globe would become enveloped in one continuous ocean. Notwithstanding these facts, and though they have been the object of prolonged study, no theory as to the cause of the movements has commanded universal acceptance. While some hold that the shrinking of the globe by cooling and the efforts of the crust to adapt itself to the shrinking interior are the prime causes, others maintain that the scale on which folding and overthrusting in the crust have taken place is out of all proportion to the shrinking that can be attributed to such a cause. During the meeting the collections of fossils and rocks in the new Sedgwick Museum, adjoining the hall in which the section's proceedings took place, were open and largely visited by members.

Questions of heredity and experimental breeding were prominent in the proceedings of Section D as w T ell as in the president's address. Exhibits were included, thus Miss Saunders showed a selection of stocks; Mr. Bateson, fowls and sweet peas; Mr. Darbishire, mice; Mr. Hurst, rabbits; Mr. Staples-Browne, pigeons; Mr. Doncaster, the Aleraxas moth; Mr. Locke, maize; and Mr. Biffers, wheat. Professor H. F. Osborn gave a lantern lecture on the evolution of the horse, and Professor J. C. Ewart and Professor W. Ridgeway described their investigations on the same subject. Professor Ewart's Celtic ponies, to which allusion was made, were on view in the court adjoining the Sedgwick Museum of Geology. Professor E. B. Poulton, of Oxford, delivered an address on the mimetic resemblance of Diptera for Hymenoptera, and Professor Gary N. Calkins, of Columbia University, one on the germ of smallpox. Other subjects having medical as well as strictly zoological interest were accounts of miner's worm and cancer research. Professor C. S. Minot, of Harvard University, read papers on regeneration, telegony and the Harvard embryological collection.

Before the Geographical Section there were several popular illustrated lectures, one on the work of the Scottish Antarctic Expedition, by Mr. W. S. Bruce, its leader; one by Mr. Silva White, on the unity of the Nile Valley, and one by Dr. Tempest Anderson, on the Lipari Islands and their Volcanoes.

The next section in the alphabetical order. Economic and Social Science, also contained a good many popular addresses and papers. The topic for special discussion was the housing of the poor by municipalities, but free trade and protection were naturally prominent in view of the present national interests.

The sections for engineering and physiology were the most technical in the character of their discussions. In the latter Sir John Burdon-Sanderson opened an important discussion on oxidation and functional activity, or the relation between oxygen and the chemical processes of animal and plant life. Experimental psychology was included under physiology. In botany Professor H. Marshall Ward and Professor Jakob Eriksson, of Stockholm discussed recent work on the biology of the fungi, especially the uredineae, and Dr. F. F. Blackman gave an account of his experimental researches on the assimilation and respiration of plants. In a paper of general interest Lord Avebury discussed the forms of stems of plants, showing that they anticipated engineering work in the economical use of the strength of materials.

The establishment of a Section of Education has added considerably to the popular interest of the meetings. Among the subjects under discussion were school leaving certificates; the national and local provisions for the training of teachers, and manual instruction in schools. Discussions took place on the reports of committees; one Douglas W. Freshfield.

President of the Geographical Section.

William Smart, LL.D.

Adam Smith Professor of Political Economy, University of Glasgow. President of the Economic Science and Statistics Section.

on influence of examinations on teaching, and on the course of experimental, observational and practical studies most suitable for elementary schools, and one on conditions of health in schools.

A special session of the anthropological section was devoted to the question of an anthropometric survey of Great Britain and the alleged deterioration of the people. Mr. J. Gray outlined a plan that had been presented to the Privy Council committee according to which the United Kingdom would be divided into 400 districts, in each of which a representative sample of about 1,000 adults of each sex would be subjected to a large number of measurements and observations. The whole of the school children would be measured, because a thousand of each sex for each age interval of one year would be required, which would amount to about the whole of the school population. The survey would be completed once every ten years, and the total number measured in that time would be about 800,000 adults and 8,000,000 children. It is much to be hoped that the work of the Bureau of American Ethnology may be enlarged so that a similar survey may be made in the United States. Professor D. J. Cunningham and Dr. F. C. Shrubsall read papers, the latter discussing the relations of the blond and brunette types and the fact that the former tends to disappear in cities.

Mr. Balfour, who presided over the meeting, remarked that the progeny of every man who won his way from the lowest ranks into the middle class was likely to diminish because of later marriages in that class. Hence it seemed that, as the state so contrived education as to allow this 'rising' from a lower to upper class, by so much did it do something to diminish the actual quality of the breed. It was, of course, not an argument against the state's attitude towards education in this respect; but there was, or seemed to be, no escape from the rather melancholy conclusion that everything done towards opening up careers to those of the lower classes did something towards the deterioration of the race.

In a survey such as this, it has of course only been possible to select from the programs and printed abstracts a few topics from the large number which came before the sections. They indicate, however, the general subjects now engaging the attention of scientific men and call to mind the names of a few of the leaders of science of Great Britain. It seems that on the whole the more eminent British men of science are more likely to attend the meeting of their general association and to take a part in its proceedings than is the case in this country, and it appears also that Great Britain has, at least in the physical sciences, more eminent men than we have.