Popular Science Monthly/Volume 76/February 1910/The Swedish Kristineberg Marine Zoological Station

| THE SWEDISH KRISTINEBERG MARINE ZOOLOGICAL STATION |

By Professor CHARLES LINCOLN EDWARDS

TRINITY COLLEGE

NESTLED among the outcropping granite ledges and islands of the west coast of Sweden, lies the village of Fiskebäckskil, near which on Skaftö has arisen the Kristineberg Marine Zoological Station. The primordial mass of the surrounding rocks and hills was planed off in curved and deeply-scratched surfaces by the vast ice-sheet of the glacial epoch. From the crests of the hills one can see the blue waters of Gullmar fjord penetrating inland and, off to the west, beyond Gasö, Flatholm and others of the protecting archipelago of islets, the white capped waves of the Kattegat.

Lichens and mosses partly incrust the rocks, and from every soil collecting crevice, grass and wild flowers give life to the hills near at hand, while at some distance the great rocks seem bleak and desolate. In these patches of wild flowers the colors are brilliant, pink heather contrasting with blue-bells and golden hökfibla. Beside the pools of

The Kristineberg Zoological Station, approached from the Bay.

The Kristineberg Zoological Station, as seen from the cliffs.

rainwater the white, downy "field-wool" waves from dried stems, and from the more shaded niches  S. Lovén. in the granite arise the graceful fronds of ferns. The large black-hooded gray crow flies from hill to hill, while on the ground the pert gray backed white wagtail nods its head and flirts its white bordered tail.

S. Lovén. in the granite arise the graceful fronds of ferns. The large black-hooded gray crow flies from hill to hill, while on the ground the pert gray backed white wagtail nods its head and flirts its white bordered tail.

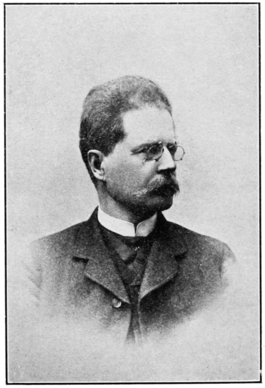

It was near the end of the eighteenth century when the Danish zoologist, O. F. Müller, made the first trawl in a form still in use for the collection of animals living upon the sea-bottom, and thus began the special study of marine zoology. Fiskebäckskil was visited for zoological research by Professor Bengt Fries in 1835. Four years later Sven Lovén and others joined the colony of naturalists, who worked with such meager facilities as the place could offer. Around the islands in the bays and fjords of the region they found a rich and interesting fauna distributed from  Hjalmar Théel. the shallow flats to depths of eighty fathoms, over bottom varying from rock, sand, shell, clay and ooze, to a carpet of grass and algæ. The foundation here of the Kristineberg Zoological Station by the Royal Academy of Science in 1877 was due to the initiative of Lovén, who had become the most famous and influential Swedish zoologist of the nineteenth century. For almost sixty years Lovén investigated problems in the morphology, comparative anatomy, embryology and taxonomy of various classes of invertebrates, especially of the echinoids, or sea-urchins. He had been a pioneer in Swedish Arctic scientific expeditions and deep-sea exploration, and hence it was fitting that he should suggest the creation of this station in the region where so much work of value had already been accomplished. It was not possible to have a good marine station nearer Stockholm on the east coast because the waters of the Baltic in former times was a vast lake and now receiving the outflow of many rivers, has a comparatively small percentage of salt, and consequently its fauna is poor in marine species. The physician A. Regnell gave the necessary funds to primarily establish the Kristineberg station.

Hjalmar Théel. the shallow flats to depths of eighty fathoms, over bottom varying from rock, sand, shell, clay and ooze, to a carpet of grass and algæ. The foundation here of the Kristineberg Zoological Station by the Royal Academy of Science in 1877 was due to the initiative of Lovén, who had become the most famous and influential Swedish zoologist of the nineteenth century. For almost sixty years Lovén investigated problems in the morphology, comparative anatomy, embryology and taxonomy of various classes of invertebrates, especially of the echinoids, or sea-urchins. He had been a pioneer in Swedish Arctic scientific expeditions and deep-sea exploration, and hence it was fitting that he should suggest the creation of this station in the region where so much work of value had already been accomplished. It was not possible to have a good marine station nearer Stockholm on the east coast because the waters of the Baltic in former times was a vast lake and now receiving the outflow of many rivers, has a comparatively small percentage of salt, and consequently its fauna is poor in marine species. The physician A. Regnell gave the necessary funds to primarily establish the Kristineberg station.

In 1892 Lovén's friend and biographer, Professor Hjalmar Théel, succeeded the founder as director and to him is due the reorganization and enlargement of the station now not only open during the summer for university students and public school teachers, but also all the year

for the investigating naturalists. Many animals which in the summer live in the depths in winter come up into the littoral belt, where their life-history can be studied to the best advantage. Almost nothing is known of the fate of the littoral fauna of the shallow bays when in winter the sand and slime in which these animals live is often frozen solid. Professor Théel's experiment demonstrated that a frozen mass of barnacles will not only resist -18° Centigrade, but revive after the ice melts and leave many young. For the solution of such physiological problems it is necessary to have the station available in winter as well as in summer. This was made possible in 1901 by a gift of 40,000 crowns from Konsul Broms, Mæcenas of the Swedish expedition to Spitzenbergen and eastern Greenland. The funds were used to the best advantage, so that now the station has a very substantial granite building in addition to the old laboratory erected in 1884. There are also three residences., a water tower reservoir and smaller houses for pumping salt-water and generating acetylene gas. A motor sloop of ten tons, the Sven Lovén, completely fitted with winding-reel, and the various patterns of trawls and dredges, as well as an enlarged granite wharf, were the gifts of Fru Anna Broms. A complete collection of well-preserved specimens illustrates the marine fauna and enables the stranger to readily identify any of the animals he may find. In a sunny room where the busts of Charles Darwin and Sven Lovén face one another, is a working library of 4,500 zoological journals, monographs and shorter papers mainly presented by Professors Théel and Retzius. Any writings not at hand can be supplied from the library in Stockholm within a few days. The station has an annual income of 10,000 crowns, 6,000 from the Royal Academy of Science and 4,000 from the Swedish government.

The grounds are fenced from the summer visitors of the neighboring Fiskebäckskil and the more fashionable Lysekil on the other side of the entrance to Gullmar fjord. The rules, firmly but courteosly enforced, establish an atmosphere of quiet. Investigators and students are provided with the animals desired, as well as all of the necessary apparatus and chemical reagents, and every assistance is most generously extended. Besides the Sven Lovén a fleet of sail and row boats is equipped and ready for the work of collecting, or for the observation of the animals in their own environment. The very slight tide makes the sea here almost like an inland lake, and gives none of the many tide-pools which constitute such an important part of the collecting grounds in our American stations.

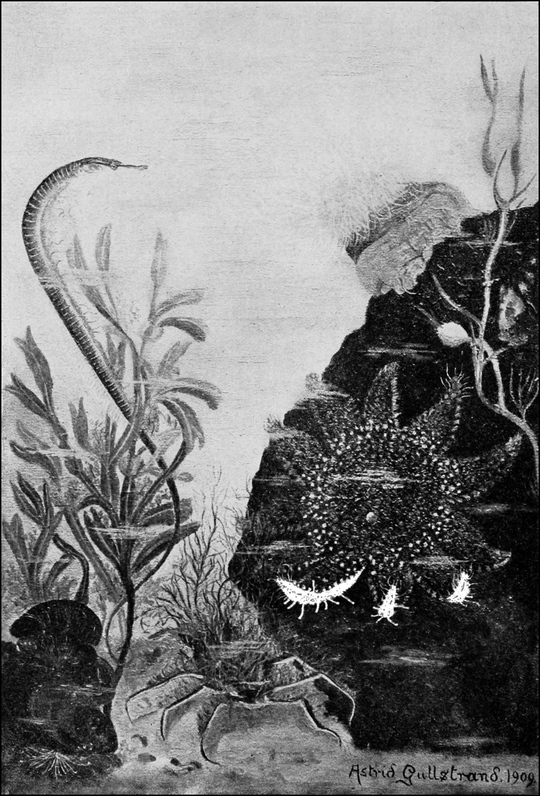

In the two laboratories there are many large and small aquaria, with such an abundant supply of sea-water that animals from a good sized shark to the most delicate coral polyp will live in contentment. The frontispiece from a painting by Fru Astrid Gullstrand represents a corner of one aquarium. The orange colored anemone, like a veritable flower, unfolds its stinging tentacles to entrap the unwary minute animals swimming by, while below, the eleven-rayed sun-star pulls itself by the contraction of hundreds of adhering sucking tube-feet. With sharp pincers the spider-crab has broken off pieces of algae and hydroid colonies and then planted them among the bristles on its back. Thus the creature is completely masked both from the game it hunts and its own carnivorous foes. The edible mussel spins strong threads from its byssus gland firmly attaching the bluish, or sometimes brownish, shell to the rock or to another mussel. Protectively colored by the olive green alga around the stem of which his prehensile tail is entwined, Nerophis, the needle-fish, as a model father, broods his young, which are glued fast to his ventral surface during development.

The station is primarily under the direction of Professor Théel as Prefect, while director Dr. Hjalmar Östergren is the very efficient administrator of affairs. Under such leadership one may feel confident that the dream of Lovén and Théel will he fulfilled and that here in Kristineberg, as at Naples, will evolve a great station, not alone for work in marine zoology but as well for the investigation of allied problems in botany, chemistry, hydrography and meteorology. Thus Kristineberg is a link in the chain of the more than fifty world encircling marine biological stations. Here and in Bergen, Kiel, Plymouth, Roscoff, Banyuls-sur-Mer, Villefrance, Trieste, Naples, Batavia, Misaki, San Diego, Pacific Grove, Cold Spring Harbor. Woods Holl, and the other sea-side stations, as well as upon the vessels designed as floating laboratories, investigators are solving the mysteries of life in the sea, the primæval birth-place of life itself.

One is reminded that it is the land of the midnight sun by the twilight lasting until after ten o'clock and the break of dawn at three, when the gulls awaken us with a chorus of hoarse cries like those of migrating geese. One of their number is the laboratory pet. It was taken, as Director Östergren naïvely remarked, "When the parting from its parents was without pain," and reared with no fear of man. It is of adult size and strong enough to fly over land or water wherever it pleases. When hungry, and that is most of the time, it sounds a shrill whistle, throwing its head up and down, until a fish is offered, when it comes to one's hand to be fed. But gradually the racial instinct has been asserted until, at the last, the gull follows the call of the wild so much of the time that little is seen of it within the laboratory precincts.

By seven o'clock the engine of the Sven Lovén is warning ns by a series of sharp explosions, accompanied by a cloud of dark smoke and fumes from the burning crude oil, that everything is in readiness for a collecting trip. We scramble aboard and Albert Henriksson, the capable draggmästaren, swings the tiller around so that we head up Gullmar Fjord.

In the distance the hills rise from the water like banks of purple mist while the nearer rocks are as clean cut as cameos. In an hour we come to the deeper waters where under fifty fathoms the beautiful red holothurians browse. Our object is to study the embryology of these cousins of the star-fish and we get them with a trawl built like the front half of an old fashioned bob-sled from which a long hood of netting runs out behind. In a half hour the engine gear is shifted and the piano-wire cable carrying the trawl is wound in. With rope and tackle we lift the great mass of slimy ooze and organisms on deck, pick out our holothurians, place them in a weighted box and again lower them to the bottom, in the hope that eggs will be laid and fertilized for our work on the unknown life-history of this species.

Again by means of the fine meshed plankton net we seek some ctenophores and in a short time a number of these exquisite ovoid jelly-fishes are found in the glass collecting-jar at the blind end of the net. Each bilaterally symmetrical body, transparent as crystal, is propelled by eight meridional rows of minute paddles, which shimmer in the sunshine like rainbows. At the upper end of the globular creature is a sac filled with clear fluid, in which delicately balanced otoliths vibrate. What does the ctenophore feel when the microscopic otoliths lightly touch the sensory cells? We know that this animal has a very primitive type of nervous system and there is experimental evidence that the apical organ responds to mechanical stimuli while it is indifferent to light. To ascertain the nature and extent of ctenophore psychology is a most difficult task. First must come the skilful, patient stimulation of each part of the animal with the most delicate physical apparatus and chemical reagents, varying the light, temperature and other elements of the environment under all the possible conditions of existence. The more difficult part however is the interpretation of the observed results of experimentation. The investigator must now be a philosopher, able to resist the inclination to regard the creature as a mere mechanism because its behavior seems so simple, and on the other hand not yielding to the temptation to project his own mind into the ctenophore when he finds its responses are an elementary edition of his own. That such primitive organisms have the psychic, just as they have the assimilative excretory, respiratory and reproductive functions,

The cliffs of Skaftö.

is demanded by the logic of the law of evolution. But just what they feel and to what degree they think is largely unknown. In the solution of these fascinating problems enduring biological research will give us knowledge where metaphysical speculation has left us groping and fencing with a jargon of terms.

Among the general problems to be solved in marine stations none are more interesting than those concerning the countless millions of organisms, that float in the surface waters as the plankton. Professor Théel has investigated these matters in the neighborhood of Fiskebäckskil since 1874 and has published important conclusions as to the origin and fate of the plankton. While most of these organisms constitute the holoplankton, always swimming freely, yet many, especially in the breeding season, belong to the meroplankton, swimming as larvæ only part of the time and then going to the bottom to form the benthon population, or to become anchored for the rest of life like the corals. One mystery at Kristineberg is that while many chætopod worms live in the bottom ooze their swimming larvæ appear but rarely in the plankton. On the other hand some forms occur at times in such masses as to make the water thick. Here, as on other seashores, the phosphorescent protozoan Noctiluca miliaris has been cast up in windrows of glowing greenish blue living fire. This tiny creature, in common with many other organisms, emits light when touched or rolled about, or upon chemical or electrical stimulation. It is possible on a dark night to read by their phosphorescence, which after all is but a secretion of their photoplasm on fire.

In the bay near Kristineberg from 1890 to 1900, the irregular sea-urchin Echinocardium cordatum occurred in large numbers but in the summer of 1902, none of the adults were found and only the young of one centimeter, or less, in size. It is the view of Professor Théel that in such cases, during some unfavorable years, the currents of the sea bear the swimming larvæ away from the ancestral breeding ground where, during their metamorphosis, they may be eaten by hungry hunters, or else sink in the abysmal waters and perish. If they find favorable bottom they will there establish a new race while the old unreplenished parent stock dies out. Thus in 1902 new larvæ of Echinocardium came to Kristineberg bay and reestablished the colony in its former home.

So animals appear and flourish in a region only to die out, while others come in to take their places. The rise of the herring fishery in these waters within the last forty years has seen the decline and practical extermination of the oyster business. In view of the fact that the planktonic larvas, while free-swimming yet depend upon the sea-currents to place them upon the right bottom, it is no wonder, that many perish in the constant struggle for existence. It is only because of the enormous production of eggs that the species does not die out. If, for instance, only one half of the descendents of one pair of cod-fish should survive, then in the third generation the whole Atlantic Ocean would be packed full of cod-fish! So overpopulation brings its own dangers when members of the same species must fight for space and food and kill one another, or migrate to new regions, before the marvelous balance in nature is readjusted.

Standing in the west wind, on the ocean-ward cliffs of Skaftö, one feels the deep-stirring obsession of the sea. It is no wonder that the Vikings could not resist the siren call of wind and wave. To-day their descendants Lovén, Nordenskiöld and Nansen, sailing forth into the great unknown, have made conquests in the realm of nature that will endure forever.