Popular Science Monthly/Volume 76/January 1910/Halley's Comet

THE

POPULAR SCIENCE

MONTHLY

JANUARY, 1910

| HALLEY'S COMET |

By Professor C. L. DOOLITTLE

THE FLOWER ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATORY

IN what will be said in this connection respecting comets in general and Halley's comet in particular, it will not be necessary to occupy much space in repetition of the well-known series of ancient views respecting the physical nature of these bodies or the superstitious dread with which they were regarded. With reference to the latter phase of the subject it may be said in passing, that it was not altogether an unfortunate matter, as without this incentive, probably even such fragmentary and unsatisfactory records of comets as have come down to us would not have existed.

These accounts are very seldom of much service from a scientific point of view. Very few seem ever to have thought it worth while to measure the position of a comet, or to record anything that would help us to-day in the determination of its orbit, or in identifying it with earlier or later appearances. It was believed that they were meteoric in character, occurring like the aurora borealis only a few miles perhaps above the earth's surface, and subject to no uniform laws like the heavenly bodies. This applies to the western nations simply. We shall see that the Chinese were at least a little more rational in their methods, though little as to their ideas on this branch of astronomy is known. There are, however, among the ancient writers, two whose utterances regarding comets are worthy of some attention, Diodorus Siculus and Seneca. The former wrote a voluminous universal history in which matters of authentic history are indiscriminately jumbled with myth and fiction, all apparently being considered of equal value. Among these, this statement occurs. "The ancient Egyptians and Chaldeans derived from long series of observations, methods for predicting the appearance of comets." As earthquakes and hurricanes were also occurrences which they were said to be able to predict, it seems to be the usual custom to dismiss the entire matter as belonging to the realm of astrology or myth, especially as nothing is said regarding the system employed. This would seem, however, to be a somewhat arbitrary procedure in view of what we know of their methods and results in other problems. It is well known that by comparison of long series of eclipses, these ancient people were able to predict their occurrence by

means of the cycle of 6,585 and one third days, or 18 years 11 and one third, or 10 and one third days, depending on whether the particular cycle included four or five leap years. It appears also, from comparatively recent investigation, that the same methods were employed in the planetary motions, and with success. It seems, then, a very natural method of procedure to attempt to find similar cycles for other natural phenomena.

In view of the apparent facility with which the cycles, real or imaginary, can be discovered by those who have a taste for such investigations, we can readily believe that the occurrences referred to were thought to fall into line, and that predictions for the future may have been attempted. It is well to remember, in this connection, that no inconsiderable part of the science of to-day is in a similar empirical status. I need only to mention the sun-spot cycle, or cycles of which there are two or three, more or less fully established, and which depend wholly upon observation. Regarding the underlying causes, we perhaps know as little as the Babylonians did of the nature of comets. The numerous attempts which are still made to fit the various phenomena of the weather into some such orderly scheme are not all confined to the ranks of the ignorant and mentally unbalanced.

The second writer alluded to, viz., Seneca, makes, what was for his time, this remarkable statement:

Greece counted the stars by their names.

It was during the middle ages that the wildest absurdities regarding comets prevailed. Their connection with plague, pestilence and famine, with battle and murder and sudden death seems to have been called in question by no one. With the dawn of the renaissance, more rational notions began to appear. At first slowly, as we might expect.

One of the first to take hold of the problem in something approaching a scientific fashion, was the renowned Tycho Brahe, 1546–1601. From observations of his own he proved that comets were heavenly bodies, certainly as distant as the moon, instead of mere atmospheric phenomena, as was commonly supposed. With regard to their orbits, however, he was far from the truth in supposing them circular. Kepler was not so fortunate here as in his planetary investigations, supposing as he did that they moved in straight lines. Finally Dörfel, a clergyman of Plauen, upper Saxony, eighty years after the death of Tycho, proved by a graphic process that the orbit was parabolic. He knew nothing, however, of the physical causes underlying this motion, but shortly after this appeared the immortal "Principia" of Sir Isaac

Newton with his remarkable demonstration relating to the motion of bodies under the action of gravity, viz., that the orbit may be an ellipse, parabola or hyperbola. Thus comets took their true place as orderly members of the system, and the last reason, if any such ever existed, for the superstitious dread of previous times disappeared. Errors, however, die hard, and this particular form manifested the usual vitality, in fact, it has not even now entirely disappeared.

The "Principia" appeared in 1687. So far as the conclusions there reached apply to the subject before us, the labor of adapting the theoretical results to numerical form and applying them to the practical problem of orbit computation, fell to Edmund Halley.

Halley, a contemporary and friend of Newton, occupies a very prominent place in the history of astronomical and physical science. Among other important discoveries and researches, may be mentioned the long inequality of Jupiter and Saturn, the proper motions of the stars, the secular acceleration of the moon's motion, method of determining the solar parallax by observations of transits of Venus, researches on terrestrial magnetism, and his epoch-making work on the motions of comets.

Halley's Comet.

| No. | Observed Perihelion. | Authority. | Calculated Perihelion. |

Authority. | ||

| (1) | 11 | B. C. Oct. 9, | Jul | Hind | — | — |

| (2) | 66 | Jan. 26 | " | " | — | — |

| (3) | 141 | March 29 | " | " | — | — |

| (4) | 218 | April 6 | " | " | — | — |

| (5) | 295 | April | " | " | — | — |

| (6) | 373 | Beg. Nov.? | " | " | — | — |

| 7 | 451 | July 3 | " | Laugier | — | — |

| (8) | 530 | Beg. Nov.? | " | Hind | — | — |

| (9) | 608 | End Oct.? | " | " | — | — |

| (10) | 684 | Oct. | " | " | — | — |

| 11 | 760 | June 11 | " | Laugier | June 15 | Crommelin-Cowell |

| 12 | 837 | March 1 | " | Pingré | Feb. 25 | "" |

| (13) | 912 | Beg. April | " | Hind | July 19 | "" |

| 14 | 989 | Sept. 12 | " | Burckhard | Oct. 9 | "" |

| 15 | 1066 | April 1 | " | Hind | March 27 | "" |

| 16 | 1145 | April 19 | " | " | April 6 | "" |

| 17 | 1222 | Aug. 22 | " | Crommelin-Cowell | Sept. 10 | "" |

| 18 | 1301 | Oct. 23 | " | Hind | Oct. 26 | "" |

| 19 | 1378 | Nov. 9 | " | Laugier | — | — |

| 20 | 1456 | June 8 | " | Pingré-Celoria | — | — |

| 21 | 1531 | Aug. 26 | " | Halley | — | — |

| 22 | 1607 | Oct. 27 | Greg. | " | Oct. 27 | Lehmann |

| 23 | 1682 | Sept. 14 | " | " | Sept. 15 | " |

| 24 | 1759 | March 13 | " | Various | March 13 | Rosenberger |

| 25 | 1835 | Nov. 16 | " | " | Nov. 15 | Pontécoulant |

| 26 | 1910 | April 8 | Crommelin-Cowell | |||

But perhaps Halley's most important work was the part which he took in the publication of the "Principia." It was largely through Halley's influence that Newton was persuaded to prepare this great work for publication, and entirely at his expense that the printing was finally done.

Among the contemporaries of Halley, we find many astronomers whose names have survived in history. We need only mention Flamsteed, the first astronomer royal, Cassini, Hevelius, Koemer and Huyghens. In his sixty-fourth year, Halley succeeded Flamsteed as astronomer royal and, at once, boldly set about the task of observing the moon through a complete revolution of the nodes, viz., a period of eighteen years, for the purpose of improving the lunar theory, a problem which had long occupied much of his attention. He had the satisfaction of completing this eighteen-year task before his death, which occurred in 1742, his age being eighty-five.

Soon after the development of Newton's method, Halley set to work with the application to comets' orbits. Certain terms were tabulated in order to facilitate the application, but even with this aid Halley himself, who delighted in large undertakings, seems to have been greatly impressed with the magnitude of this one. The undertaking consisted in computing the parabolic orbits of all comets where sufficient data existed for this purpose, but, although the appearance of some four hundred of these bodies had been noted during historic times, only twelve had been sufficiently observed to give much hope of success. To this first twelve were afterwards added twelve more. The final results of this long investigation were not published until 1749, when it appeared with the title, "Synopsis Astronomiæ Cometæ." In these days, with improved methods of attacking the problem, such a task

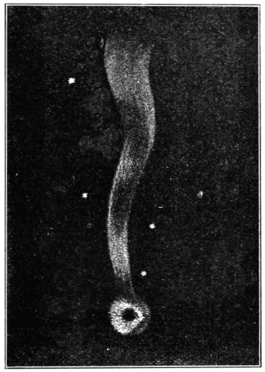

Halley's Comet in 1456 (according to Lubieniecki, Theatrum Cometicum).

would be very promptly disposed of. Of course, all computers are not like the late Professor Safford, who used to compute such an orbit in one hour, but we should probably not find it necessary to search long for one who would undertake to do the work in ten or twelve days. But the method developed by Newton seems now very cumbersome and its application laborious. It was, moreover, so far from completion

Tailless Comet of 684 (Halley?) in the Pleiades (according to Lubieniecki, Theatrum Cometicum).

that no means were found for computing the elliptic elements of a periodic comet unless it had been observed at a second return. The identification, therefore, depended on the similarity of the elements, a very uncertain criterion, as we shall see.

It is not at all improbable that if Halley had known more of the chances of failure which beset this method of identification he would hardly have ventured to predict another return of his comet. The step,

Halley's Comet in 1066, after its emergence from the Sun's Rays (according to Lubieniecki, Theatrum Cometicum).

in any case, was a bold one but, fortunately for Halley's reputation and for science, the result fully justified it.

The same process has been tried in many cases besides this one, but this seems to be the only instance where the prediction has been verified by success. Gibbon gives us a very interesting instance of this method of identification.[1] After referring to the remarks of Seneca, already quoted, he continues:

Time and science have justified the conjectures and predictions of the Roman sage: the telescope has opened new worlds to the eyes of astronomers; and, in the narrow space of history and fable, one and the same comet is already found to have revisited the earth in seven equal revolutions of 575 years. The first, which ascends beyond the Christian era 1767 years, is coeval with Ogyges, the father of Grecian antiquity. And this appearance explains the tradition which Varro has preserved, that under his reign the planet Venus changed her color, size, figure and course; a prodigy without example either in past or succeeding ages. The second visit, in the year 1193, is darkly implied in the fable of Electra, the seventh of the Pleids, who have been reduced to six since the time of the Trojan war. That nymph, the wife of Dardanus was unable to support the ruin of her country: she abandoned the dances of her sister orbs, fled from the zodiac to the north pole, and obtained, from her dishevelled locks, the name of comet. The third period expires in the year 618, a date that exactly agrees with the tremendous comet of the Sibyl, and perhaps of Pliny, which arose in the west two generations before the reign of Cyrus. The fourth apparition, 44 years before the birth of Christ, is of all others the most splendid and important. After the death of Caesar, a long-haired star was conspicuous to Rome and to the nations, during the games which were exhibited by young Octavian in honor of Venus and his uncle. The vulgar opinion that it conveyed to heaven the divine soul of the dictator, was cherished and consecrated by the piety of a statesman; while his secret superstition referred the comet to the glory of his own times. The fifth visit has already been ascribed to the fifth year of Justinian, which coincides with the 531st of the Christian era. And it may deserve notice that in this, as in the preceding instance, the comet was followed, though at a longer interval, by a remarkable paleness of the sun. The sixth return, in the year 1106, is recorded by the chronicles of Europe and China: and in the first fervor of the crusades, the Christians and Mahometans might surmise, with equal reason, that it portended the destruction of the infidels. The seventh phenomenon, of 1680, was presented to the eye of an enlightened age. The philosophy of Bayle dispelled a prejudice which Milton's muse had so recently adorned, that the comet from its "horrid hair shakes pestilence and war." Its road in the heaven was observed with exquisite skill by Flamsteed and Cassini: and the mathematical science of Bernoulli, Newton and Halley, investigated the laws of its revolutions. At the eighth period, in the year 2355, their calculations may perhaps be verified by the astronomers of some future capital in the Siberian or American wilderness.

In more recent times we have the remarkable group of bodies of which the comets of 1668, 1843, 1882 are members; there are others, the total number being probably very large. All of these bodies move in orbits almost identical, almost grazing the surface of the sun at the time of perihelion passage, and passing through millions of miles of the sun's corona. At the appearance of the 1882 member, it was fully believed by some prominent astronomers to be the same comet which had appeared in 1843, which  Halley's Comet in the Year 1682. was being rapidly drawn into the sun by the resistance encountered at perihelion passage. It appeared, however, that the orbit, derived exclusively from observations after that event, indicated a period of six hundred or seven hundred years, at least thus disposing of the question of identity. The behavior of the body itself was, however, very suggestive as to the true condition of things. After the close approach to the sun with its tremendous tidal strain, the nucleus was found to be broken up into a number of pieces. These parts, instead of approaching each other, separated more and more as long as the body could be kept in sight. At the next return, after some six hundred or seven hundred years, there will, no doubt, be four or five separate comets, following each other at intervals of perhaps a number of years.

Halley's Comet in the Year 1682. was being rapidly drawn into the sun by the resistance encountered at perihelion passage. It appeared, however, that the orbit, derived exclusively from observations after that event, indicated a period of six hundred or seven hundred years, at least thus disposing of the question of identity. The behavior of the body itself was, however, very suggestive as to the true condition of things. After the close approach to the sun with its tremendous tidal strain, the nucleus was found to be broken up into a number of pieces. These parts, instead of approaching each other, separated more and more as long as the body could be kept in sight. At the next return, after some six hundred or seven hundred years, there will, no doubt, be four or five separate comets, following each other at intervals of perhaps a number of years.

Halley's Comet in the Year 1759.

Halley's Comet in the Year 1759.

Halley confidently predicted the return of his comet in 1759. He also identified it as having been seen in 1305, 1380 and 1456. The difference of period, which amounted to one year and three months, was somewhat disturbing, but Halley assigned this to the true cause, namely, the perturbations produced by Jupiter and Saturn. He remarked that the period of the planet Saturn might vary as much as a month from the action of Jupiter. He says:

As no method existed at that time for precise determinations of the perturbations, there was considerable uncertainty as to when to look for the next return, but Halley estimated that the general result would be a retardation, and that it would not be visible much before the beginning of 1759. This, as we shall see, proved to be a very fortunate guess.

Naturally, the old chronicles were now diligently searched for records of earlier appearances. Beginning with 240 b.c., a continuous series of supposed appearances is found at an average interval of 76.8 years, but with the very considerable range of a little more than five years between the longest and shortest of these periods. With such a range, naturally, the period alone furnishes a very slight foundation for establishing identity, and, unfortunately, in many cases, the accounts given are so meager and unsatisfactory as to leave the matter in grave doubt. In a number of instances, where the comet has been connected with natural events, such as conjunctions of planets, eclipses, earthquakes and the like, or with important matters of history, the accounts may contain, in connection with much rubbish, sufficient material of value to leave no doubt as to identity. It has been thought by many that this is the comet mentioned by Josephus in connection with the destruction of Jerusalem. This would, perhaps, not be impossible, though a considerable stretching of the period would be required. The appearance in A.D. 451 is the first record which seems open to no doubt on the score of identity. In the autumn of that year the Huns, under Attila, were defeated by the Roman armies. Numerous historians and chroniclers of that day agree that this event was announced by a comet, which proves to have been this one of Halley. To eclipses of the moon, April the second and September the twenty-sixth of this year, assist in fixing the date securely. The second of these eclipses is charged to the account of the comet itself. The return in 1066 has received much attention on account of its supposed connection with invasion of England by William, the Norman, and with the overthrow of Harold at Hastings.

By 1456 something more like scientific activity had begun. It was indeed nearly one hundred years before the publication of the immortal work of Copernicus, and astronomical observers were few and far between, particularly in Europe. In recent times a series of observations has been brought to light, made by Toscanelli in Florence. The discovery was made by Celoria, in 1885, and, as may be supposed, it is a most welcome addition to our data for fixing the exact circumstances of this appearance. Perhaps never before or after has a comet caused so much consternation as upon this occasion. Three years before, the Turks under Mahomet the second had taken Constantinople and their armies were pushing their conquests to the west. Many were apprehensive of the complete subjugation of Europe. Then a brilliant comet appeared, the precursor, as was supposed, of further calamities, and a universal panic seems to have taken possession of high and low alike. Who wonders if the pope ordered the church bells to be rung everywhere at noon, and that all should then engage in prayer for the protection against the Turks and the comet?

1531 is one of the dates used Halley in fixing the character of the orbit, the other two being 1607 and 1682. This appearance is known as the comet of Apian, that is, Petrus Apianus, alias Peter Bienewitz, court astronomer of Charles V., and of Ferdinand I. His observations

extended for three or four weeks, and were made at Ingolstadt. Apian first established the fact that the comet's tail is constantly directed away from the sun. This was the first substantial item of evidence towards showing that comets, instead of being simply terrestrial phenomena, are in some way connected with the cosmic universe. The system of Copernicus had not then appeared, so the true solution of the problem could not be expected, though here at least was a beginning. Earthquakes, showers of blood and fiery appearances in the heavens are charged to this comet, but from now on, we have less and less of these matters. The next appearance, 1607, was detected by Kepler, though it had been seen a few days before by a monk in Swabia. Kepler furnishes a series of observations from September 26 to October 26, but he was less fortunate in his speculations regarding its nature and movements than had been his lot in his planetary researches.

The year 1682 brings us again to Halley. In these attempts to identify the early appearances, the Chinese annals have been of great assistance. In some cases all of the substantial evidence which we possess comes from this source. These records were kept in a much more systematic manner than the chronicles of the western people. The times when the comet was first and last seen are carefully recorded. The path, observed among the stars, is often given, not, of course, with extreme accuracy, but sufficiently so as to admit of the determination of an approximate orbit, and thus furnish valuable data for identification. The Chinese appear not to have been disturbed by the superstitious dread of comets which pervaded Europe. Their accounts of the physical characteristics are unsatisfactory, the length of tail and similar matters being given, not in angular, but in linear, measure, which, of course, means nothing.

Much was done, between 1682 and 1759, in the way of advancing the principles and methods of celestial mechanics. It was now possible, as it was not seventy-five years earlier, to determine the effect of the planetary perturbations and thus reduce to narrow limits the uncertainty as to the time of appearance. The matter does not seem to have been taken up seriously, however, until 1757, when Clairaut, who had already proved himself a brilliant mathematician, attacked the problem. Elaborate discussions of the problem of three bodies had already been developed, but they were not adapted to this case, on account of the great eccentricity of the orbit. This made it necessary to attack the problem in a very different manner from that employed in the case of the moon and the planets. Clairaut, however, proved himself equal to the task, though the practical application involved an immense amount of numerical work, and the time remaining was short. He was ably assisted, however, by Lalande, then a youth of seventeen, and a lady, Madame Lepaute.

The final result indicates a retardation of 618 days, 518 being due to the action of Jupiter, 100 to Saturn. The time of perihelion passage was fixed at April 13, 1769, but, as it had been necessary for want of time to abridge the work, by omitting some small terms, Clairaut stated that the true time might differ from this by as much as a month. He states further that a body passing into regions so remote, and which is hidden from our view during such long periods, might be exposed to the action of forces, totally unknown, such as the

attraction of other comets or even of some planet, too far removed from the sun to be even perceived. It should be remembered that nothing was known at this time of Uranus and Neptune. The actual time of perihelion passage was March 13, just within the limit.

The history of its discovery is interesting. Though astronomers everywhere were looking forward with great interest to the event, the most elaborate attack was made at Paris. This was planned by De Lisle, but the work of searching for the body fell to Messier, whose name is familiar to astronomers everywhere in connection with the discovery of numerous comets, nebulæ and clusters. He had a genuine

passion for this class of work, but no taste whatever for theoretical research. At this time he was living in the house of De Lisle, who seemed to think that he had a property right in Messier's observations, which Delambre tells us he hoarded as a miser does his wealth, neither using them himself nor allowing any one else to do so.

De Lisle planned a systematic siege of the stronghold. Assuming limits which he believed wide enough for the purpose, he prepared charts on which lines were drawn for convenient dates, the supposition being that the comet would be found somewhere on the line. Night after night for eighteen months, Messier carried on the siege until, finally, on January 21, 1759, he was rewarded with his first sight of the comet. It was doubtless humiliating to all concerned to learn that on Christmas eve, previous, the comet had been seen by a peasant named Palitzsch. Delambre states that he saw it with the naked eye, without previous knowledge of its existence, but this is not the true history. The account given by Palitzsch is quite different. He states that he was engaged in observing the variable star, Omicron Ceti, with his nine foot tube, and that he found between Delta and Epsilon Ceti a nebulous Apparent Orbit of Halley's Comet from October 2, 1908, to December 7, 1909. 1908 (1) Oct. 2, (2) Nov. 25. 1909 (3) Jan. 15, (4) March 3, (5) April 15, (6) May 25, (7) June 31, (8) Aug. 3, (9) Sept. 3. (10) Sept. 30, (11) Oct. 26, (12) Nov. 17, (13) Dec. 7.

star which proved to be the comet. There were not wanting skeptics who doubted whether the comet would be found, but its return put an end forever to the old notions, and left no foothold for the opponents of Newton's theory of universal gravitation.

The prediction for the next return was taken in hand, in due time, by no less than four distinguished mathematicians—Damoiseau, Pontécoulant, Lehmann and Rosenberger. These found, respectively, for the time of perhelion passage, 1835, November 4, 13–15, 26 and 12. This time the perturbations due to Uranus and the earth were included as well as those of Jupiter and Saturn. The actual time proved to be November 16.

Search for the comet began, on the part of numerous comet seekers, as early as January, 1835, but the first sight of it was obtained August 5, by Dumorchel, at Rome, very near the predicted place. About the middle of September, two months before perihelion, it became visible to the naked eye. The greatest brilliancy occurred about the middle of

October. The public had been expecting something very striking, but, unfortunately, cloudy weather interfered to a great extent. It practically disappeared from the northern hemisphere with perihelion passage, but was followed for some time longer by Sir John Herschel at the Cape of Good Hope.

As regards the present appearance, the comet is already with us. The preliminary searching on this occasion has been greatly facilitated by photography, a resource not available on previous occasions. More than a year ago, as soon as this region of the sky had fairly emerged from the sun's rays, the campaign began at a number of observatories, in this country and Europe. The results were negative. Dr. Wolf, of Heidelberg has the honor of being the first to detect the comet on one of his plates, and is apparently the first who succeeded in photographing it. The first plate to show it was taken August 28, but he did not venture to announce it until September 11. At Greenwich two plates were taken September 9. At first nothing unusual was detected, but, after hearing of Dr. Wolf's discovery, a reexamination showed faint images on both plates. It has since been photographed and observed visually at several places. On the seventeenth the first view was obtained of it at the Flower Observatory.

The observed place differs from the computed one in right ascension 24s, and 4′ in declination, bringing the time of perihelion passage to April 20.0. Another result gives the time of perihelion, April 18.63.

The nearest approach to the earth will be in May 19, the distance about 14,000,000 miles. On May 18.14, Greenwich mean time, the earth and comet will be in heliocentric conjunction. It is not unlikely that on this date the earth will pass through the tail.

At the meeting of the Astronomical Society, 1908, a committee on comets was appointed, with the understanding that special attention

should be given to this one. The plan which this committee hopes to carry out involves a constant watch of the comet, to be undertaken by a series of observers, so situated in latitude and longitude that the comet will never be lost sight of, except, of course, when it is in conjunction with the sun. A continuous series of photographs, taken in this way, on practically a uniform plan, will go far, it is hoped, toward the solution of some of the puzzling questions in connection with the physical behavior of these bodies, particularly with the rapid and peculiar change of the tail. The committee reports that good progress is being made towards carrying out their program. For the purpose of bridging the long interval between the Pacific coast and eastern Asia, Mr. Ellerman, of the Mount Wilson Observatory, expects to go to Honolulu early next spring.

- ↑ "Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire," Vol. IV., p. 289.