Popular Science Monthly/Volume 77/August 1910/The Progress of Science

THE WORK OF THE NEW YORK ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY

The Zoological Society has performed an important service for the city of New York by the establishment and conduct of a Zoological Park and later by taking charge of the Aquarium. The relations of the society to the city are similar to those of the trustees of the American Museum of Natural History, of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Botanical Garden, but are somewhat unusual. In each case the city provides the buildings and the cost of maintenance, while a private corporation supplies the collections and is responsible for the conduct of the institution. The plan appears to have worked very well, as j each institution has had a strong organization, free from any political control, but effective in obtaining large appropriations from the city and considerable private gifts.

The fourteenth annual report of the Zoological Society lays emphasis on increasing the scientific work done both at the park and the aquarium. The institutions have been extremely successful in gathering and maintaining large collections of animals and interesting the public in them; but they have not as yet been able to undertake

i research work comparable in value. The director of the aquarium writes in his report, "The small aquarium at Naples has made Naples famous." It is not, however, the exhibition tanks, but the research work and publications

1 of the station which have added to the fame of Naples. The entertainment and instruction of the public is an important function for the city to undertake, and the money devoted to these purposes at the Zoological Park and the Aquarium is well spent. But money used for research is not spent at all; it is invested for the permanent benefit of all the people. Zoological gardens have hitherto emphasized scientific work less than have botanical gardens, but there are problems of comparative psychology and comparative pathology to which collections of

The Administration Building of the New York Zoological Society.

animals might be made to lend themselves admirably; and there are many kinds of research work in experimental morphology and heredity which might be carried on to advantage. While paying their cost in exhibits of general interest and unusual instructiveness to the public, they would at the same time advance science and its applications.

The report of the executive committee begins with the paragraph: "With this year closes the first period of the Zoological Park development, and from now on the work of the society will be, to an ever increasing degree, in the direction of the remaining objects of the society. Briefly stated, those objects are, scientific work in connection with the collections, and the protection and preservation of our native fauna." The director of the aquarium also urges the desirability of establishing a small staff of scientific curators. We may consequently expect that in a short time the contributions to science from the Zoological Park and the Aquarium will rival those from the Museum of Natural History and the Botanical Garden.

The director of the Zoological Park urges the need of additional bear dens, a zebra house and an aviary for eagles and vultures. He expresses the hope that these three buildings may be obtained during the present year and states that with these the animal! buildings and other installations for exhibits will be practically complete. During the past year an administration building has been erected at a cost of $75 000. It is intended for executive offices and as a meeting place for the members, and is to contain a library and art gallery. At present a collection of some 600 heads and horns, in which the director has taken much interest, is housed in this building, but a separate building open to the public is planned.

The attendance at the park last year was 1,614,953, an increase of 200,000 over the preceding year. There were 5,000 animals on exhibition representing 1,117 species, of which 812 were mammals, 2,880 birds and 1.308 reptiles. This is an increase over 1908 of 155 species and 421 specimens, including many of special interest.

The attendance at the aquarium reached the remarkable record of 3,803.501,

George Frederick Barker.

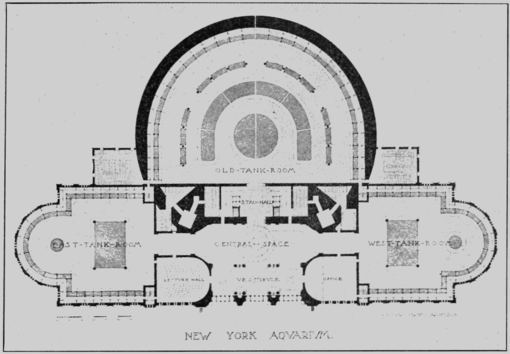

an increase of a million and a quarter in a single year, and probably a larger number of persons than visited any other institution in the world for scientific entertainment and instruction. There were no increases in the collections, as there is no room for them. The director very properly urges the desirability of enlarging the aquarium and providing laboratories for scientific work and men to carry it forward.

DEATHS AMONG AMERICAN MEN OF SCIENCE

Since the death of Mr. Alexander Agassiz, in April, we have lost three other American scientific men officially placed among the hundred who are most eminent by their membership in the National Academy of Sciences. They are Professor George Frederick Barker, General Cyrus Ballou Comstock and Dr. Charles Abiathar White.

Professor Barker, who was both a

chemist and a physicist, was born in 1835 and graduated from Yale in 1858 and later in medicine from the Albany Medical School. He held various positions, including the chair of physiological chemistry at Yale until 1873, when he became professor of physics at the University of Pennsylvania, and for thirty-seven years, latterly as professor emeritus, held a leading position in the university, when Philadelphia had a more dominant position in science than it has been able to maintain. Professor Barker was an admirable lecturer and the author of widely-used text-books of chemistry and physics; he served as expert in important legal cases and carried forward research work of consequence. He was elected to the National Academy in 1876 and was president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1879.

General Comstock, born in 1831, graduated from West Point in 1855 and taught physics in the academy. He was actively engaged in the civil war, first in the defenses of Washington and later as chief engineer and senior aide-de-camp to General Grant. Later he became superintendent of the geodetic survey of the great lakes and of the improvements at the mouth of the Mississippi, and published works on these and other engineering topics. He was elected to the National Academy in 1884, and in 1907 gave the academy a fund of $10,000 for the promotion of researches in electricity magnetism and radian energy.

Charles Abiathar White, born in 1826, though early interested in science, was late in beginning professorial work. He received a degree in medicine at the age of thirty-seven and three years later became state geologist of Iowa and professor of natural history in the state university. He accepted a chair in Bowdoin College in 1873 and two years later became geologist in the surveys of Powell and Hayden. For many years he was connected with the Geological Survey, the National Museum and the Smithsonian Institution. He was elected to the National Academy in 1889. He published over two hundred contributions to geology, zoology and botany, maintaining his scientific activity to the end, as is indicated by an article in a recent volume of this journal.

Mr. Agassiz and Professor Barker died at the age of seventy-five, General Constock at the age of seventy-nine, Dr. White at the age of eighty-five. Another American scientific man who played an important part during the second half of the last century and died with his life work fully accomplished was Professor William Phipps Blake. He was born in 1826 and made valuable studies in the mineral deposits and geological structure of the Rocky Mountain and Pacific coast regions. Dr. Amos Emerson Dolbear, for thirty-six years professor of physics at Tufts College, known for inventions and other work in physical science, has died at the age of seventy-three years. Professor Robert Parr Whitfield, of the American Museum of Natural History, eminent as a geologist, has died at the age of eighty-two years. Dr. Cyrus Thomas, archeologist in the Bureau of American Ethnology since 1882, well known for his contributions to anthropology, has died at the age of eighty-five years.

More grievous than the death of veteran men of science is the loss of those whose work is not accomplished. Charles Reid Barnes, professor of plant pathology in the University of Chicago, dying after a fall at the age of fifty-two, was among our leaders in botany in both performance and promise. Dr. H. T. Ricketts, also of the University of Chicago, but called to the University of Pennsylvania, died in Mexico City at the age of thirty-nine years from typhus fever contracted as a result of research work on that disease. Even this partial list shows how severe have been the losses by death from among American men of science during the past six months.

SCIENTIFIC ITEMS

The Paris Academy of Sciences has conferred the Janssen Prize, consisting of a gold medal, on Director W. W. Campbell, of the Lick Observatory.—• Professor Theodore W. Richards, of Harvard University, has been invited by the Chemical Society (London) to deliver the next Faraday lecture. This will be the tenth Faraday lecture, the others having been given as follows: Dumas, 1869; Cannizzaro, 1872; Hofmann, 1875; Wurtz, 1879; Helmholtz, 1881; Mendeléef, 1889; Rayleigh, 1895; Ostwald, 1904; Emil Fischer, 1907.—Dr. John Benjamin Murphy, professor of surgery in Northwestern University, has been elected president of the American Medical Association, for the meeting to be held next year at Los Angeles.