Popular Science Monthly/Volume 78/May 1911/The Progress of Science

CIRCULATING PROFESSORS

Harvard and Columbia Universities have for several years maintained an exchange of professors with the Prussian government, and both universities have recently made similar arrangements for Paris. Columbia has had at least one visiting professor from Copenhagen, and Wisconsin has recently obtained a Karl Schurz endowment for German professors. Each of our leading universities has lectureships which are frequently filled by foreign men of science and scholars; and there are certain extra university courses, such as the Lowell lectures in Boston and those of the Brooklyn Institute. Thus during the month Professor Svante Arrhenius, of Stockholm, has been giving the Silliman lectures at Yale University; Professor L. T. Hobhouse, of London, lectures at Columbia, and Sir John Murray, of Edinburgh, a course of Lowell lectures. Our students and teachers have for years gone abroad in swarms; foreign students are beginning to frequent our universities, and foreign men of science, scholars and publicists to visit our institutions. Several international congresses have been held in this country and others will follow in due course.

All this exchange of men and ideas has been stimulating and fruitful. Up to the present we have on the whole played the part of the provinces, paying men to come to us and paying for the privilege of visiting them. We have in the main been content to exchange our money for their ideas. With other American republics and with Japan and China conditions have been reversed. With the older European nations they are changing; collectively they still overshadow the United States, but we can compare our institutions and our culture with I those of Germany, France or Great Britain on tolerably equal terms.

The official exchange of professors with Berlin has probably been the least successful part of this movement. The visiting professors learn, but their teaching is not particularly profitable. Books and journals are better ways to communicate to one country the scientific work of another, and the foreign language is a bar to oral teaching. A German professor lecturing in his own language for a week in each of twenty American universities would perform a more useful service than in attempting to give regular class-room instruction in one of them. Incidentally it may be noted that attendance at court functions or failure to attend them seems not to cultivate the sense of humor of the American professor.

The eastern seaboard plays somewhat the same part toward the western and southern sections as Europe does to the United States. Students from other parts of the country frequent the eastern universities and their professors lecture elsewhere. But the first official arrangement for an exchange of professors among American institutions has just been announced by Harvard University. A professor is to be sent annually to four colleges in the middle west—Colorado, Grinnell, Knox and Beloit—spending an eighth of a year at each, and the college sends one of its junior officers to Harvard, where he takes part in the regular instruction and may at the same time pursue graduate studies. The scheme is doubtless intended to draw students to Harvard and in a sense usurps the functions of the state university. But it appears to be on the whole commendable. It is certainly desirable for the officers of the smaller and more 1 emote institutions to retain or form associations with the work of the large universities. The professor from the large university may also gain by first-hand knowledge of educational conditions elsewhere. There is, however, a risk that we may by such means cultivate the i traits of the propagandist and exploiter; rather than those of the scholar. This is the danger to which the American professor is exposed and from which he has not escaped.

We may hope that the Harvard plan is the initiation of a larger movement which would be wholly beneficial. The colleges of each state should be allied with the state universities or with the private corporations standing in its place. There should be a free exchange of professors and students between all parts of the country. Then there should be a great national university at Washington or elsewhere frequented by advanced students and professors from all parts of the country and all parts of the world—men who would gladly learn and gladly teach. Harvard, Columbia and Chicago, Michigan, Wisconsin and Illinois may be secondary centers, but they should cooperate to establish a super-university, which would have the same relation to existing universities that these should hold to the colleges.

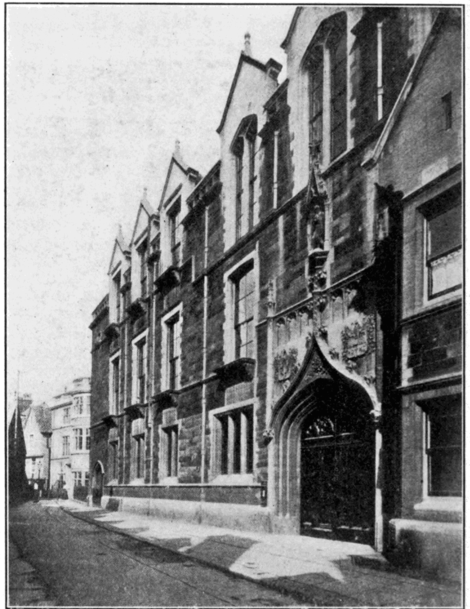

THE CAVENDISH LABORATORY OF CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY

Certain centers of research and scholarship are national and international in character. It seems that there would be advantages in greater division of labor, so that one subject or group of subjects would be especially favored at each university. To a certain extent this happens under existing conditions, for a department which is strong is likely to become stronger, while a weak department does not readily improve. But there are usually se%eral universities having departments of about equal strength in a given subject and graduate students find the leading men widely scattered. A large group of students and teachers working m the same field exerts an enormous influence.

A real world center of this character is the mathematical and physical work of Cambridge University, maintained since the time of Newton. The Cavendish Laboratory for experimental physics, established forty years ago, has had in its directors three men of remarkable distinction, Clerk-Maxwell, Lord Rayleigh and Sir J. J. Thomson having in succession filled the Cavendish professorship. At the end of 1909 Sir J. J. Thomson had completed twenty-five years of service and to commemorate a tenure of office so full of achievement his colleagues have prepared a volume giving a history of the Cavendish Laboratory, from which we borrow the facts and the pictures of this note. The book contains a series of chapters in which the Clerk-Maxwell period is reviewed by Professor Schuster, the Rayleigh period by Mr. Glazebrook, and the tenure of Professor Thomson by himself and a number of the former students of his laboratory, including Professor Rutherford. There is given a list of memoirs, containing an account of work done in this laboratory and a list of those who have carried out researches in it. They number more than two hundred, including distinguished investigators in all parts of the world.

The practical teaching of physics and laboratories equipped for research are of comparatively recent origin. At Paris, Oxford and London there were but modest beginnings, when the Duke of Devonshire, then chancellor of the University of Cambridge, gave about $40,000 for the erection of the Cavendish Laboratory completed in 1874. It was enlarged at a cost of $20,000 in 1896, and again in 1908, mainly through the gift of Lord Rayleigh of the greater part of the Nobel prize for physics awarded to him in 1904. According to American standards the investment in the building is modest, but not so the accomplishment of the men who have directed it and worked in it.

J. Clerk-Maxwell was Cavendish professor of experimental physics from 3871 until his untimely death in 1879, Professor Fleming writes that one of his great courses of lectures on electrodynamics was attended by only one other student, but Hicks, Schuster, Chrystal, Poynting and Glazebrook were among those who worked in the laboratory. Maxwell's investigations on electricity, magnetism and light were in the main theoretical, and their epoch making importance was fully recognized only after his death; but he exerted great influence on teaching and research in experimental physics.

Lord Rayleigh succeeded Clerk-Maxwell in 1879 and retained the chair until 1884, when he retired to his private Terling Place estate and laboratory. During the period of his professorship he completed his exact measurements of electrical units and other researches of fundamental importance. Regular courses for students were established and women were admitted to the laboratory.

J. J. Thomson, then in his twenty-seventh year, was elected to succeed Lord Rayleigh. He had come to  James Clerk-Maxwell. Cambridge from Owens College and was second wrangler in the mathematical tripos of 1880. Thereafter he began in the Cavendish Laboratory his experimental and mathematical researches, publishing on the electric and magnetic effects produced by the radiation of electrified bodies in 1881 and on the theory of electric discharge in gases in

James Clerk-Maxwell. Cambridge from Owens College and was second wrangler in the mathematical tripos of 1880. Thereafter he began in the Cavendish Laboratory his experimental and mathematical researches, publishing on the electric and magnetic effects produced by the radiation of electrified bodies in 1881 and on the theory of electric discharge in gases in  Sir J. J. Thomson

Sir J. J. Thomson

From a painting by Arthur Hacker. 1883. Thomson was prepared to assimilate the discoveries of Lenard, Röntgen and Becquerel, and has made the Cavendish Laboratory under his direction the great center for the newer physics and the discoveries of the nature of radiation, electricity and the constitution of matter.

SCIENTIFIC ITEMS

We record with regret the deaths of Dr. Henry Pickering Bowditch, professor of physiology at the Harvard Medical School  Lord Rayleigh.

Lord Rayleigh.

From a painting by Sir George Reid. for thirty-five years; of Dr. Samuel Franklin Emmons, of the U. S. Geological Survey, eminent for his contributions to the scientific study of ore deposits, and of Mrs. Ellen Henrietta Swallow Richards, instructor in sanitary engineering in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Dr. Theobald Smith, professor of comparative pathology in Harvard University, has been appointed visiting professor at the University of Berlin, for the second half of the academic year 1911-12.—Dr. Edna Carter, instructor in physics at Vassar College, has been awarded the Sarah Berliner research fellowship for women. She will continue her work in physics at Cambridge under Professor J. J. Thomson, and in the laboratory of Professor Wein, of Würzburg, where she received her doctorate.

Dr. C. G. Abbot, director of the Astrophysical Observatory of the Smithsonian Institution, will this summer conduct an expedition to southern Mexico to make measurements of the sun's radiation, which will be compared with simultaneous observations on Mt. Wilson. The congress has made a special appropriation of $5,000 for this work.

The subscription to the memorial to President Grover Cleveland exceeded $100,000 on the seventy-fourth anniversary of his birth. It will be remembered that the memorial is to be a tower forming part of the graduate college of Princeton University.—Mr. James A. Patten has added $50,000 to the $200,000 which he had given to the Northwestern Medical School for the study of tuberculosis.

In the New York senate on March 21 a bill was introduced to incorporate "The Carnegie Corporation of New York." The incorporators named in the bill are Andrew Carnegie, Senator Elihu Root, president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Dr. Henry S. Pritchett, president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; William H. Frew, president of the board of trustees of the Carnegie Institute of Pittsburgh; Robert S. Woodward, president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington; Charles L. Taylor, president of the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission; Robert A. Franks, president of the Home Trust Company, and James Bertram, Mr. Carnegie's secretary. Under the language of the bill the incorporators are authorized "to receive and maintain a fund and apply the income to promote the advancement and diffusion of knowledge among the people of the United States, by aiding technical schools, institutions of higher learning, libraries, scientific research, hero funds, useful publications, and by such other agencies and means as shall from time to time be found appropriate."