Popular Science Monthly/Volume 80/February 1912/The International Hygiene Exhibition at Dresden

THE

POPULAR SCIENCE

MONTHLY

FEBRUARY, 1912

| THE INTERNATIONAL HYGIENE EXHIBITION AT DRESDEN |

By Dr. HENRY G. BEYER

MEDICAL DIRECTOR, U. S. NAVY, U. S. DELEGATE TO THE EXPOSITION

There is not a single visitor who does not regret the shortness of the existence of this great exposition; who did not feel his interest in it increasing daily, while in attendance; who would not welcome an opportunity of returning to it for more instruction and inspiration; who was not moved to wish that every living man and woman might receive the benefits this exposition was intended to convey and to disseminate.

All expositions are schools of learning of the most practical sort. International expositions are the universities in which the different nations teach each other. The exhibits, carefully selected and arranged in groups, represent the achievements of many years, the results of many years of study and labor, in a predigested form and ready to enter the understanding without requiring any effort on the part of the observer, except that he be in a receptive mood. There was a time when the attributes of usefulness on the part of the high arts and sciences were regarded as detracting from their value; when the beauty of an object was thought to end where its usefulness began; when sciences, we were told, had a right to exist for their own sake and regardless of their usefulness to mankind. Human physiology itself, during its juvenile development in recent years, had become so precociously independent as to barely recognize its ancient relationship to mother Medicine. What a remarkable change of front in this general attitude has been made in a few years, was perhaps never better shown nor more efficiently demonstrated than in the "Internationale Hygiene Exposition, Dresden, 1911," where one great, intelligent, strong mind succeeded in gently pressing the fruits of every known art, science and industry into the service of humanity. Disciplined, orderly cooperation toward one common and useful end and purpose was never and nowhere shown to better advantage than in the work of organizing, creating and conducting to a successful termination this truly great exposition. By no means the least that can be said of it is that it proved to be a financial as well as a scientific and philanthropic success.

A General View of the Exposition Grounds

The exposition grounds cover in all an area of 320,000 square meters, of which 70,000 square meters are occupied by buildings, 72 in all, large and small. This immense area was contributed partly by the "Grosse Garten," partly by the Royal Botanical Garden, the park of Price John George and the Dresden Commons. The Lenné-Strasse, dividing this area, was bridged over. One of the first serious difficulties in planning with which the Dresden architects were confronted was to so distribute their buildings that the large fine old linden trees in these various parks should not be damaged. This difficulty they succeeded in overcoming to perfection. They distributed the various buildings in such a manner as to make the trees serve as a rich green background for them, thus, at the same time, avoiding rigid geometrical lines and producing, instead, a most picturesque effect.

The main entrance to the grounds consists of three rows of large and imposing columns, covered in above. Passing through these columns, and to the right of the main entrance we find the administration building which houses the various offices of the director, assistant directors, the post offices, the fire department and the sanitary and red cross companies, all excellently and most efficiently organized; to the left stands a very large structure containing the assembly hall, intended for the meetings for the large number of congresses that met in Dresden during the summer, the various exposition halls for school hygiene and the care of children, exhibition rooms for dental hygiene, tropical hygiene and chemical industries, for infectious and venereal diseases.

From the enclosed oblong square, the visitor overlooks a larger open space and notices in the distance the imposing structure devoted to popular hygiene which is marked above the entrance in large and imposing letters, "Der Mensch." This imposing structure has a prominent, semicircular entrance, divided by a series of large columns, 11 meters high, surmounted by a cupola and leading into a spacious vestibule, on either side of which are wardrobes, and, finally, into a magnificent hall, with a stage or podium at its furthest end for giving seating capacity to the officers conducting various meetings, with their guests of honor. Against the background of this stage there is visible a large statue with the inscription "No Wealth is equal to thee, Health!" This entire building is devoted to popular hygiene. Passing down the wide steps of the first open square, we find ourselves entering a large open enclosure in the grounds. This is the so-called "Festplatz." On the sides of this Festplatz are various small stores, a

music pavilion, garden restaurant, to the right a wine restaurant with a terrace above and the recently erected pavilion of Great Britain. Farther to the left and overlooking the garden restaurant there is the permanent exhibition building of Dresden, artistically embedded among the new buildings. On the left, also, and against the botanical garden we find the recreation park. This park is occupied by a very original Bavarian restaurant, a hippodrome, a place for dancing, an academic Beer-kneipe, Japanese and Indian tea-houses. This recreation park proved a great necessity in that it accommodated the overflow of sightseers and gave them a chance to rest and refresh themselves, lending at the same time variety to scenery and interest to sightseers, without interfering with the intended serious character of the exposition.

The city exposition palace, Steinpalast, forms the center of the exposition; this palace had to undergo extensive interior changes to accommodate the historical and ethnological sections, some of the most remarkable features of the whole exposition. While exhibiting most effectually the contrast between past and present conditions as regards hygiene, it also showed and illustrated what we hear so often without attaching any profound meaning to it, namely, that there is nothing new under the sun, and what we call new, in reality, embodies an old and identical idea in a new garb.

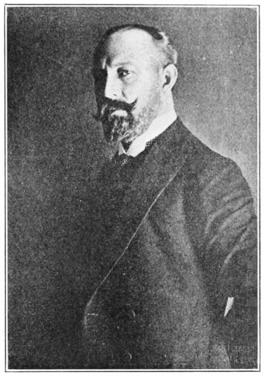

Dr. K. A. Lengner,

Dr. K. A. Lengner,

President of the Exposition.

Connected with the Steinpalast by large halls is the "Hall for Chemical Industry" and scientific instruments. To the right of the large "Festplatz" and between it and the "Grosse Garten" and amidst a long row of fine large linden trees, there runs along an avenue, 40 meters wide, along one of the sides of which foreign nations have erected their pavilions. China has erected a pavilion in the form of a pagoda. Austria has built a large-sized rectangular structure with a massive roof, high walls, large windows and wide imposing entrances. Russia has erected a building after designs made by a Russian architect and resembling in style some of the buildings seen in the Kremelin. Japan, likewise, has contributed a rectangular structure, after a national design, simple but most effective in displaying the exhibits. Switzerland, has put up a building characteristic of the Bervese  Netherlands, Spain, Italy, France, Hungary and Amsterdam all have erected pavilions in style of architecture exhibiting the national characteristics in their design. This "rue des nations" shows off well at night when illuminated. Passing out of the "rue des nations" and around the end of the botanical garden, we come in sight of the several large halls, housing life-saving devices, means for the care of the sick and injured, traffic on land and sea, appliances used in the care of prisoners and the insane, army, navy and colonial hygiene. A sylvan restaurant stands at all hours ready to administer to the physical need of the visitor.

Netherlands, Spain, Italy, France, Hungary and Amsterdam all have erected pavilions in style of architecture exhibiting the national characteristics in their design. This "rue des nations" shows off well at night when illuminated. Passing out of the "rue des nations" and around the end of the botanical garden, we come in sight of the several large halls, housing life-saving devices, means for the care of the sick and injured, traffic on land and sea, appliances used in the care of prisoners and the insane, army, navy and colonial hygiene. A sylvan restaurant stands at all hours ready to administer to the physical need of the visitor.

A number of smaller buildings, devoted to various purposes, such as the care of the crippled, the housing of the poor, sylvan burial of the dead, the rearing of various species of rabbits for food purposes, a model stable for cows and clean milk production, form the outskirts of this part of the exhibition grounds.

Passing now over the bridge across the Lenné-Strasse which separates the two main divisions of the exhibition grounds, we may either climb the few steps that lead up to the bridge or simply step on the inclined surface of a sidewalk, in constant motion, carrying passengers up at the expense of two and one half cents. The bridge leads the visitor over into the second great division of the grounds. Here we find, on the right, the large hall for occupational hygiene, on the left the power-house; facing the visitor is the gigantic hall marked "Settlement and Habitation,"

one of the richest, so far as contents are concerned, of the whole exhibition. Passing the music stand and turning to the left, we have, on the left, an Abyssinian village; on the right several small and large restaurants and enter a large open space having on one side the large hall devoted to the hygiene of clothing and the general care of the body, on the other the hall exhibiting nutrition, dietetics and food stuffs, while facing us, in the distance, there is the large oval for sports with its stadium, music stand, grandstand, restaurant and sport laboratory, as well as the immense swimming tank called "Undosa." In this swimming tank, artificial waves about three feet high are produced by mechanical means and the bather gets the benefit of an open air bathing resort nearer at home.

The sport laboratory is fitted out with all sorts of scientific instruments and apparatuses to investigate scientifically the effects of physical exercise on the human body, especially on heart and lungs. A gymnasium shows the usual development instruments well stocked with material. The great oval is for out-of-door meets and is almost daily in use.

In thus decentralizing the interesting points of the exhibition, the administration was parting company with the principles of housing everything under one roof and thus made a new and very attractive innovation. It avoided overcrowding of the visitors and divided them by a variety of interests located in different halls; it reduced the danger of a large fire, hoping, in case there should be one, to limit it to one or a part of one building by a system of hydrants most generously distributed through the grounds. Through this division of subjects among a large number of buildings it was possible for the visitor to pursue his studies on the subject he was interested in especially, without being disturbed and crowded out by visitors interested in other pursuits.

The Exposition Buildings

One of the most noteworthy features of the exposition was the architectural beauty of the buildings, including their interior decorations. While the designs of the various buildings differed from each other individually, their structural execution showed that they belonged to the same genus, while all were artistically adapted to the more practical purposes which they were intended to serve. Made principally of wood, all exposed surfaces were provided with a fireproof, coarse-grained covering. Gay, but superfluous, bunting, likely to catch fire and calculated to detract the visitor's eye from the main objects of the exposition, was carefully avoided, while a fine sense of artistic finish, calculated to invite the visitor to concentrate his attentions on the chief objects of the exposition, was everywhere apparent. The quiet, serious character of the buildings, their generous dimensions, large door-ways, wide passage-ways, an abundant provision of light and air, were features without attracting special attention to themselves, that were nevertheless in the most perfect harmony with the serious purposes and the hygienic characters of the exhibition and aided materially in sustaining instead of fatiguing the attention of the visitors.

The Exposition

It could never have been our purpose to attempt giving a full description of this exhibition. Such an undertaking would require a whole corps of editors and end in the publication of a long series of illustrated books. The intention here is to give only a very brief review of a few chapters in the greatest living handbook of hygiene ever put together and for which the exposition stood from the beginning and to which high purpose, in reality, it remained true to the end.

Steinpalast

plan and organize the exposition, was in no department of the exhibition better shown than in the historical division. There was to be no mere comparison between what hygiene is now and that which it represented fifty years ago, but the problem before the organizers was to trace the whole history of hygiene from the remotest beginnings to the present time and to illustrate this gradual evolution by pictures, models and objects, actually dating from those times.

Among the prehistoric Kelto-germanic exhibits could be seen foodstuffs, etc., dating from the stone age. A wall picture from a slightly later period displayed the remarkable fact that the wasp-like waist so much admired on the part of the female sex to-day had been already the ambition of the prehistoric woman. To ward off disease by the wearing of amuletes was already then in vogue.

Prehistoric Babylon shows that, in these remote times, the most detailed precautions were already taken for keeping all sorts of insects off from food articles, especially during the serving of them. The hygienic tendencies of old Babylon are shown in the technique employed in the construction of their wells, canalizations, bathing establishments, latrines and burial systems. The practise of isolating cases of infectious disease, of cleaning food-stuffs before they were eaten and of setting aside a fixed number of days for rest and recreation, was already then commonly observed in Mesopotamia.

The significance of old Jewish hygiene is abundantly shown, in the directions on the treatment of articles of food, the regulation for sexual intercourse, the treatment of excrements, burial rites, instituting the regular sabbath which has conquered the world, the priestly inspection of lepers, preserved in old and time-honored rolls of the Tora and further illustrated by sketches, photographs and models.

In prehistoric Egypt,the manifest tendency of preserving the human body after death for a future life in an unchanged form is hygienically considered the most interesting. That the sun-dried soil of Egypt contributed largely to the results obtained is shown when original mummies are compared with the results obtained by artificial drying of animal bodies. To what an alarming extent organized disease producers had been at work thousands of years ago, on the Nile, is abundantly shown in a large collection of preparations of Egyptian origin in glass bottles.

The statues of the Venus of Praxiteles and of the Doryphoros of Polyklet serve to show how much attention was paid already in those early times by the Greeks to the care and systematic development of the human body from early childhood throughout adult life. That the goddess Hygeia stood in great esteem in ancient Greece is shown in citations from Grecian poets. Models of the recent excavations of the town of Salona in Dalmatia show us a typical Roman provincial town with its splendid streets, water-supply and sewer systems and bathing establishments; a third model, also, shows one of the thermal establishments of Imperial Rome, that of Caracalla. Storerooms for provisions, grain mills and kitchen hearths of Greco-Roman culture are shown in the form of models. Wall pictures complete the illustrations of the dietary customs of ancient Rome and Greece. Numerous models of Etruskan and Sardinian types of houses showing the construction of latrines, the methods of lighting and heating, their bathing establishment, treats exhaustively of the home life of these times.

A special room is devoted to showing how great and thorough were the hygienic precautions promulgated in both Greece and Italy. These

ancient framers of the laws already knew the great value to the state of strong and healthy people as shown by the laws they promulgated. Food adulterations also received their due share of attention. But the most significant hygienic characteristic of ancient Rome and Greece centers undoubtedly in the methods of street construction, water supply systems and sewerage systems.

Another special room is devoted to showing the efforts of the physicians of those ancient times as being not alone those of restoring the sick to health, but also those of preventing the well from becoming sick. A plan of the sanatorium in Kos shows its sanitary situation on the south side of a hill covered with trees. Mothers were made to nurse their own children or substitute a wet nurse; the bottle came into consideration only as a feeding instrument of children during the second year of their lives.

The last room of classical antiquity is devoted to burial customs. It is here shown that cremation was not the exclusive method of disposal of the dead in classical antiquity.

We shall have to pass over the different epochs that mark the progress of hygiene during the middle ages, which was shown and interestingly emphasized by a great variety of exhibits, collected from all parts of the world and contributed at great expense, distributed through 22 rooms, both large and small, and in which that gradual but steady progress was shown by graphic, plastic and pictorial exhibits from the time when physicians diagnosed disease by simply looking at the urine-bottle of their patients, up to the period when hygiene began to be taken more seriously and entered into the dignified domain of an experimental science.

We must, likewise, pass over the ethnological portions of the exhibition, although most interesting and highly instructive in showing the customs and habits of the different races peopling our globe and their common desire for a long, happy and healthy life.

In leaving the historical and ethnological groups of the exhibition, one can scarcely turn aside an ever-increasing impression of the existence of a great variety of distinct and widely differing species of the genus homo. Even if a common origin for all should finally be accepted, it will have to be admitted that the genus man has shared in the tendency of all life in general, namely, that of producing varieties, differing almost as widely from each other in their habits and productions as do the various organs in a single individual living animal organism in their functions. The study of the comparative physiology and psychology of races (ethnology), therefore, teaches us that their respective manners, customs and achievements differ in accordance with their hereditary composition and will continue to do so to the end of time.

About 450 individuals and firms had sent contributions to the historical group of the exhibition alone.

The German Workingmen's Insurance

The handsomely bound catalogue by Dr. Klein for the special exhibition, intended to inform the visitor of the work accomplished by the German workingmen's insurance, covering 107 pages, and filled with but the briefest mention of the objects exhibited, will give an idea of the wealth of the material found in Hall 10, presided over by Dr. jur. et med. Kaufmann and Geh. Eat. Weger. The workingmen's insurance, instituted in 1885 by Emperor Wilhelm I., pursues the object of protecting the workingmen against the unavoidable dangers of their calling. Every working man and woman within the boundaries of Imperial Germany is, regardless of nationality, legally insured against disease, accident, invalidity and old age. The sums of money thus contributed to the various workingmen's societies reach the limits of the incomprehensible

To mention only the sums contributed in this way during the year 1909:

| Marks | ||

| Sickness insurance | 342,200,000 | |

| Accident insurance | 162,266,000 | |

| Invalidity insurance | 189,029,000 | |

| Total | 693,495,000 | or |

| Daily | 1,900,000 |

The comprehensiveness of the machinery of the workingmen's insurance is beautifully illustrated in the picture of an oak and its effect on the whole body of workingmen is intended to be shown by a figure representing a workingman, designed by Professor Hosaeus, Berlin.

Race Hygiene. Director Dr. von Gruber, Munich

Race hygiene has for the first time found a place in hygienic exhibitions. It had for its object the calling of the general attention of the public to the immense importance of heredity upon the prosperity and the degeneracy of the race, upon the inherited constitution which, when strong, bids defiance to unfavorable conditions, when weak, succumbs in spite of the most careful nursing. The public at large must learn to appreciate the necessity for exercising a reasonable amount of care in the selection of a life partner.

With the aid of 200 tables, charts and colored natural objects, the laws of heredity were demonstrated and it was shown how, through the continuity of germ plasm, in plants and animals, different characteristics are transmitted from one generation to another. The different kinds of variability, as fluctuation and mutation, are made clear. The laws established by Mendel, together with the results of the latest experiments on the transmission through heredity of acquired characters and of diseases, have received due regard.

Attention is also devoted to the question as to whether the nations of the highest culture are increasingly degenerating. The dying out of certain distinguished families and the decrease in number of those fit for military service is taken into account. The special toxic influence of alcohol and syphilis on germ plasm as well as the influence on the race of inbreeding and race-crossing is considered. Finally, the significance of the intentional prevention of conception, or the Neomalthusianismus on the race problem is shown. For further details we must refer to the very comprehensive guide, published by Max v. Gruber and Ernst Rudin, for use in this group of exhibits. This book possesses a value of its own, beyond its mere usefulness as a guide through the momentous group of exhibits.

Sport Division

The organization of the sport division of the International Hygiene Exposition, Dresden, 1911, marks an important epoch in the history of bodily exercises. A rigid classification of sports according to physiological principles has, for the first time, been rigidly carried out. The scientific committee is represented by such men as Professor Zuntz, Berlin, Professor Schmidt, Bonn, E. von Schenckendorff, Görlitz, and many other eminent and learned men. The so-called German Sport Committee stands under the protectorate of the German Committee of Olympic Games: Eæz. von Podbielski, U. von Oertzen and Dr. Martin, presidents, and with the chairmen and secretaries of the large German societies as members. The real working committee is the organization committee under the presidency of Dr. Becker. The special divisions under this organization committee are: academies, fishing, automobile and motor sports, aviation, boxing, ice and snow sports, fencing, women sports, golf, hockey, chase and shooting, bowling, lawn-tennis, military wheel-field-riding sports, roller skating, rowing, swimming, sailing.

gymnastics and gymnastic games, wandering and mountain climbing. The members of the individual groups were selected from and by the associations distributed over the whole country. From the above an idea may be gained of the comprehensiveness of the organization. The sport exposition was divided into the following subdivisions:

1. Special gymnastic exhibitions by the different unions.

2. Scientific division.

3. Industrial sport division.

4. Sport places and sport plants.

5. Sport laboratory and library.

6. Tournaments.

In the sport laboratory were made:

1. Anthropometric and ergographic investigations.

2. Electrocardiographic examinations.

3. Röntgen-ray observations.

4. Examinations on the chemistry and mechanics of respiration.

5. Microscopic and chemico-physiological investigations.

A dark room and a library completed the laboratory. A large number of university men had voluntarily contributed their services to the success of the work. The object of this laboratory was to furnish material for the laying of a foundation for a scientific sport-physiology and sport-hygiene. From results already obtained in this laboratory, some of which I had an opportunity of examining, I am convinced of the fact that a beginning has at last been made for the scientific elaboration of the proper principles upon which alone the different forms of exercise may be made useful and beneficial, instead of hurtful and dangerous as most of them are now. German sport is intended to remain an amateur sport; it is not to be a wild record breaking mania and struggle for money premiums, to satisfy the overwrought ambitious few; it is not to satisfy the curious wishing to see celebrated champions. The time-honored title of sportsman is to be denied to those who witness a tournament simply because they want to bet on the results. Professionals who are in it for what they can get out of it are not to be called sportsmen; the German sportsman is to remain a gentleman, active without being greedy for gain. The pleasure in tournaments, a national characteristic, is not to be discouraged, but it is not to be regarded as the highest aim of sport. A sentiment for out-of-door sport is to reach the entire nation; it is to bring the individual citizen from his office and workshop out under the influence of God's sunlit nature, to enable him to stretch his limbs and to fill his lungs with oxygen and his mind with the beauties of nature.

Manly virtue, endurance and resistance are to be placed above calcified arteries, enlargements of hearts and collapse. To this program the sport division of the exposition has remained true throughout.

The Significance of the Hall, Marked in Large Golden Letters, "DER MENSCH" at the Internationale Hygiene-Ausstellung

The conventional attitude in fashionable society of displaying an unconscious ignorance with reference to everything concerning the structure and functions of the different organs of the human body is gradually losing the character of its traditional respectability. The forces at present operative in shaping the destinies of human races have rendered such a display of lack of knowledge culpable to a degree and its further cultivation a crime. The most formidable governing power in any free and enlightened country being.admittedly based upon a sound public opinion, itself a function of the degree of the general health of its citizens, it clearly becomes the duty of every individual to contribute to this constitutional asset of his commonwealth, in proportion to his personal intelligence and educational standing, as the most valued tax that can be levied on his citizenship, for it seems pretty well acknowledged that the future will belong to the nation possessing the greatest number of strong, healthy and physically as well as mentally resistant individuals.

As a contribution to the methodology of disseminating such knowledge among the people in the most effectual manner, the hall of popular hygiene at Dresden stands preeminent in recent times. Structure and functions of the human body were never before presented in a more easily assimilable form. The conditions necessary for the preservation of health and for the prevention of disease were never before set forth in so easily intelligible a manner. Neither expense nor pains had been spared to render clear to the understanding the mysteries of health and disease. All the available arts and sciences had been pressed into service of this great object. The systematic representation of the subject was pursued with great consequence. An introductory lecture was given in the great hall every morning. A culture of living protozoa was projected on the screen in an adjoining dark room, their life histories explained. In another dark room, the production of antibodies in the blood, excited by the action of bacteria, was shown on the screen. Then, the life cycle of the silk worm and the preparation of silk was similarly shown on the screen. Over one hundred microscopes, all in the most perfect working order, and under a splendid system of illumination, served to demonstrate monocellular organisms, mitotic cell-division, fertilization and embryonic development as well as the adult cellular structure of every organ in the human body.

The gradual development from a single cell of some of the lower animals as well as intra-uterine development of the human embryo was beautifully shown by a series of embryos rendered transparent by the method of Spalteholz. A splendid series of wax and plaster models in

glass cases, greatly assisted by attached mechanical devices, helped the understanding of their structure and function.

Care of Children in the Middle Ages.

Care of Children in the Middle Ages.

Costumes of Modern Times. The subject of nutrition was given a prominent place. The more elementary chemical substances constituting the principal natural food products were shown in glass bottles and, further, shown by charts to which the percentage number of each elementary substance was attached, with the daily amounts of each required by man. Against a wall, there were arranged the quantities of water, salts, proteids, fats and carbo-hydrates which man consumed in a year and in the form of natural foodstuffs. At another table we were introduced into the mysteries of food adulteration and shown how cinnamon was made out of brick dust, pepper out powdered linseed oil-cake and strawberry syrup without strawberries.

Costumes of Modern Times. The subject of nutrition was given a prominent place. The more elementary chemical substances constituting the principal natural food products were shown in glass bottles and, further, shown by charts to which the percentage number of each elementary substance was attached, with the daily amounts of each required by man. Against a wall, there were arranged the quantities of water, salts, proteids, fats and carbo-hydrates which man consumed in a year and in the form of natural foodstuffs. At another table we were introduced into the mysteries of food adulteration and shown how cinnamon was made out of brick dust, pepper out powdered linseed oil-cake and strawberry syrup without strawberries.

The toxic substances contained in alcohol, tea, coffee and tobacco and their influences on longevity and human happiness were all exhibited in a most tangible form. Table and kitchen utensils of the most varied composition and form were shown in separate cases.

A special group was devoted to housing, showing the best methods of heating, ventilating, illuminating and cleaning our dwellings.

In the group of occupational hygiene the visitor was shown the dangerous influences to which workmen are exposed in the different factories and the beneficial appliances recently devised and put into operation to prevent them.

The visitor was thus prepared to pass into the section in which the common infectious diseases of man were shown, how they originate and how they are best prevented, at the same time exhibiting busts of the most noted men of science who have contributed most to our knowledge in this department of sanitation.

A most noteworthy feature also was the development, care and best mode of nutrition for nurslings; it was here shown that the care for the child must begin before birth and must extend to the mother. Of great interest were the demonstrations given on the subject of nutrition of the nurslings; their weight and size, the treatment of the diseases of children, the care of the skin, the duration of sleep, etc.

A most telling story is also told on the subject of dental hygiene.

The department of the general care of the body to be observed during childhood, adult manhood and old age is most impressive and so plainly told and shown as never to be forgotten.

When we add to all this that daily demonstrations in every one of these groups were given by the most eminent men of science, engaged for the whole time of the exposition, it is easy to explain the ever-increasing number of visitors to this hall and the fact that, towards the last part of the exposition, the hall had to be opened at night on special admission tickets, sold, to satisfy this ever-increasing thirst for knowledge. It simply had become thoroughly recognized that it was within the capacity of every man and woman to accumulate, in this hall, sufficient knowledge of the laws of health to provide for oneself that modicum of health which forms the most solid foundations of all human happiness. It had become realized as never before that health means bodily, mental and moral perfection, its cultivation resulting in strength, beauty and happiness.

Foreign Pavillions

Amsterdam.—The city of Amsterdam had contributed valuable exhibits. The most interesting from the hygienic viewpoint were undoubtedly those of the city health office, consisting in tables, curves and microphotographs, the results of the chemical and bacteriological examination of food-articles and condiments; the control of infectious diseases and the ways and means employed in fighting their spread. Most interesting also were the exhibits demonstrating the difficulties experienced in Amsterdam with regard to its water-supply and the ingenious methods employed by its people to overcome them.

Brazil.—Those unacquainted with the amount and high character of work done, in recent years, in Brazil, by the public health authorities there, were surprised to see the wonderful exhibits in the Brazilian pavilion and to witness the daily kinematographic demonstrations of the actual field work done in that country, to fight yellow fever and other infectious diseases. The sanitary service of Brazil seems to be well organized and the work is done by the most improved methods and with the use of modern instruments. Completely equipped laboratories of bacteriology, chemistry and pathology are at the command of the sanitarian. Thus, under the sanitary supervision of Dr. Oswaldo Cruz, now continued by that of Dr. Figueiredo de Vasconcellos, the pioneer leaders in this work, Rio de Janeiro is now free from yellow fever and one of the healthiest cities on the Atlantic coast of South America.

China.—The government of China, through the erection of its beautiful pavilion, filled with exhibits covering all the present departments of hygiene in the Chinese Empire, has succeeded in demonstrating its interest in and desire for the introduction of hygienic methods into the country. The members of the Chinese commission

have been instructed by their government to study hygiene and sanitation in all the European states, with the view of applying these methods to the needs of the people inhabiting the Chinese Empire. The opportunities for the beginning of such a study could never have been more advantageous than they were at the exposition of Dresden.

England.—Under the high protectorate of H. R. H. Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein and the presidency of the Right Hon. The Lord Mayor of London, a British National Committee, numbering about 250 members, was formed at the eleventh hour, for the purpose of giving the British people an opportunity of giving expression of their sympathy with the exhibition and its high aims, by contributing their exhibits and thus largely adding to the completeness of the results of the undertaking. Being an almost daily visitor at the British pavilion for several weeks, and, attending the daily demonstrations by Dr. Armit, I can not but express my great admiration at the completeness of the exhibit got up in so short a time and covering almost every department in hygiene. A pavilion several times its size could scarcely have held any more than did this small pavilion of Great Britain. Much of this success, of which the British people may feel proud indeed, is no doubt due to the personal efforts of Sir Thomas Barlow, The Right Honorable Lord Ilkeston, Professor G. Sims Woodhead, the executive committee, and to the untiring energy of its skilful and learned executive secretary and demonstrator, H. W. Armit.

France.—The pavilion erected by the government of the Republic of France, was one, characteristic of the eighteenth century French architecture, designed by M. Tronchet, the architect-in-chief of the French government. Beautiful in construction and appearance, it was further favored by location.

The French executive committee, of which Professor Fuster was chairman and Drs. Calmette and Landouzy members, had been obliged to adhere to a program of exhibiting none but objects of an administrative and philanthropic character. If industrial exhibits were nevertheless accorded a place they only served the purposes of demonstrating the progress made in technique employed in vaccination, disinfection, canalization, sterilization and the methods of water-supply.

The bulk of the exhibits consisted in collections of drawings, paintings, photos, models, relief maps, charts, showing the achievement of French scientists along hygienic and philanthropic lines. A most creditable as well as a most beautifully arranged exhibit.

Japan.—The pavilion of Japan, planned by Dr. ing. C. Ito of Tokio and executed by Alfred Pusch, Dresden, was characteristic of the country, simple, impressive, artistic, economical as well as adapted to its purposes. The commission sent by Japan consisted of eight representatives of the government, famous for the work they had done in their respective lines and one of the best known among which was Professor Dr. Miyajima, of the Imperial Institute for Infectious Diseases of Tokio.

The exhibits covered almost every department of hygiene, making this exhibition one of the completest in this respect among foreign pavilions. A fine model of Fujiama greeted the visitor on entering. The beauties of the country, its climate, were abundantly shown by models, drawings, pastels, photos, etc. The hygiene of nutrition, of clothing, the methods of housing and living, education of children in schools and homes, the care of the sick, safety devices, the prevention of epidemics, the history of development of medical sciences in the country all have received careful attention. But most impressive, if not positively inspiring, were the exhibits and background paintings showing the work of the sanitary corps while an action was in progress as well as that of the army field kitchen.

A special pavilion, "Formosa," under the special care of Dr. Takaki, served to show the great sanitary improvements made by the government of Japan since it had taken possession of that island.

Italy.—In spite of the fact that Italy, during 1911, had to supply three different expositions of its own, namely: Rome, Turin and Florence, it found means of erecting and supplying a pavilion of its own in Dresden. The six groups into which the exhibits were divided were arranged in very good taste, giving and making a rather artistic impression. The exhibits were for the most part statistical and graphic.

Austria.—Austria's pavilion was one of the largest and perhaps the richest of all the foreign pavilions erected at the exposition. It represented a multum in parvo of the whole subject of hygiene and no simple description could do it justice; we must refer to the special catalogue find guide, published by the administration, for a detailed list of the exhibits and of the distinguished names of their contributors, as well as the corps of managers who had charge of this pavilion.

Russia.—Russia had been one of the first foreign countries declaring its readiness to erect a special pavilion at Dresden. The pavilion is a two-story structure designed by Professor Pokrowsky, St. Petersburg, and forms perhaps the largest foreign pavilion. As regards the contents, we can only repeat what was said of the Austrian pavilion, namely, that they covered the whole subject of hygiene.

Switzerland.—The exhibitions in the Swiss pavilion were divided into ten chief and three special groups, extending over the entire field of hygiene. .These exhibits served to place the small republic in the front rank of hygienic countries and reflect the greatest credit on its national committee of 100 and its executive committee, of which Drs. H. Carrière, W. Kolle, Ost and Schaffer were members. Of quite special interest to military men was a new and quite well-adapted wheeled army field-litter,

Spain.—Spain had erected a neat-looking pavilion, the exhibits consisting for the most part of graphic and pictorial wall charts, statistical tables, etc., very artistically arranged. Drs. Pulido and Chicote, the Spanish representatives, received their commissions too late to enable them to collect a more representative exhibit. The exhibits nevertheless showed that Spain is awake to the progress in all departments of hygiene, plainly demonstrating its keen interest by its participation in the exposition in Dresden.

Hungary.—The visitor to the exposition would hardly have looked for a special pavilion representing Hungary after having seen the one erected by Austria. But so great was the interest of the Hungarian government in the exposition and its high aims at Dresden, so much had been done there in recent years to improve the hygienic conditions of its people and its institutions and so different from those of other countries were the hygienic requirements of Hungary, that the Hungarian exhibits, many of which were quite original, aroused and sustained the interest which they so well deserved. The special catalogue and guide, by Professor Emil von Grosz, covering 48 pages, must be allowed to speak for the rich collection seen in this pavilion. Special sympathy was aroused with the visitor on the subject of those institutions which were devoted to the governmental care of abandoned children. The Hungarian people believe that every abandoned child has a right to be cared for by the community.

United States.—If absence, ever before, was conspicuous anywhere, it was the absence of a United States pavilion at the exposition at

Dresden, 1911. The "humiliating blush of shame" anticipated in my letter to the American Public Health Association (Am. Jour, of Public Hygiene, Nov., 1910, p. 858) could be seen on the face of every American at the exposition and realizing the gravity of the situation. While the flags of every civilized nation could be seen floating merrily to the breezes, the stars and stripes were missing. The humanitarian eye among its stars played no part in, had no sympathy with, no contribution to offer for, this most Christian endeavor to raise the hygienic standard among the nations of the world, so fundamental to international happiness and international peace which we so loudly acclaim. While the real cause of this may never become known, the stain, created by this demonstration of indifference, will remain a lasting reproach to the American people, especially to its public health officers.