Popular Science Monthly/Volume 80/January 1912/The Problem of City Milk Supplies

| THE PROBLEM OF CITY MILK SUPPLIES |

By P. G. HEINEMANN, Ph.D.

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

MILK and various dairy products have been used by the human race for ages. There is evidence to show that at least 50,000 years have elapsed, probably a much longer period, since man began to use cow's milk for his own purposes. Savages who have no historical records consume milk—sweet, sour and fermented—to a large extent and have made use of the preservative properties of sour milk for keeping meat from putrefaction. The scriptures mention the fact that milk, sour milk and butter were common articles of food among the Hebrews. The ancient Greeks and Romans used milk and cheese and among the ancestors of the Anglo-Saxon, German and Scandinavian tribes the dairy herd was an important asset.

Perhaps the antiquity of the dairy industry is responsible for the extreme conservatism practised. The methods of taking and handling the raw material—milk—remain primitive to this day. Although forming one of the most important and universal articles of food, of special value in the feeding of infants, little progress has been made in that part of the production of dairy products, which is the controlling one from the public health standpoint, namely, the process of gathering the milk and its treatment before it reaches the consumer, the dairy or the creamery.

The sciences of hygiene and bacteriology are of relatively recent origin and with them came the knowledge that wholesomeness of food as well as sanitary environment is for the most part a matter of cleanliness. Now, few things are farther from cleanliness than the ordinary manner of milk production. Even if we admit that "pigs is pigs," milk is not always the same, and milks from different sources may vary enormously. Who has not seen a barn, where cows, horses and pigs are stalled under the same roof? Filth, cobwebs, dust, manure are allowed to accumulate and at long intervals are shoveled to a place, which is not far from the barn, where they dry out and are blown in the form of dust into the barns. Ventilation in the barn is absent, screens to keep out the disease-carrying flies are rare, light is admitted by small windows and the cows are permitted to rest in their own filth, which covers the hide, dries and is brushed or shaken into the milk when this is drawn from the udder. The modern cow is covered with filth and the owners ridicule the suggestion that cows deserve more care than horses. The cow, which furnishes the most valuable food for the human race, is thus neglected, while the horse, which is used for work only, is kept in good condition. Even from financial considerations should cows receive great care.

And what is the condition of cleanliness of those who attend to the milking? Do they change their clothes for-clean ones before milking? Do they wash their hands? Far from it. Any suit of clothes, covered in some cases by dirty overalls, is good enough for tending the cow. The hands are not washed and just before milking are wetted with milk, water or even with saliva. Thus the dirt is washed from the udder into the milk. The virus of contagious diseases is sometimes carried from

the milker to the milk and epidemics of serious nature are thus started. Not least in importance is the universal presence of flies in cow barns. Flies may act as carriers of disease germs and should be kept out of barns as much as possible. It is true, that when entering barns the cows are bound to carry some flies with them, but by careful screening and by cleanliness of the floors and walls the number can be reduced to a minimum.

Such is the food we consume every day, such is the food which we depend upon for bringing up our babies, if the mother is unable or unwilling to nurse her offspring. A careful mother will clean the bottle, which serves to carry the food for the baby. The farmer thinks his duty is done if he washes the milk pails and other utensils with ordinary cold water. The water is sometimes obtained from wells situated in dangerous proximity to the outhouse, or from streams which carry sewage from neighboring farms or settlements. After washing the receiving pails in a careless manner there is enough milk left in them to cause disagreeable odors, but, nevertheless, the fresh milk is drawn into these vessels.

Milk is destined by nature to feed the young of mammals. They suck it directly from the teats and the danger of dirt being taken with the milk is comparatively small. But we take the milk from the cow under artificial conditions and have to use precautions and safeguards to prevent dirt from being mixed with the milk. The "cowey taste" sometimes innocently supposed to be characteristic of fresh milk, is due to nothing but cow manure, which has been suspended and become part of the milk during the process of milking. It has been estimated that the population of large cities consume hundreds of pounds of cow manure daily with milk.

What does the farmer do with the milk after his cans have been filled? In many cases the cans have no covers and instances are known where open cans are kept over night in filthy barns. Odors are taken up readily by milk and chickens and other fowl find comfortable places for roosting on the cans. The amount of milk sold that contains little or no filth is small. Such milk is necessarily higher priced than ordinary milk, as many precautions have to be observed to produce it. It is higher priced, however, only in a sense. By paying more for each quart we get a pure article with full food value, and have a reasonable assurance that no diseases are communicated that way. Thus there is really a saving, as diseases are always expensive.

How is it feasible to procure milk which is satisfactory from the standpoint of the sanitarian? The principal thing is that the consumer demand a good product and he must know what constitutes good milk. It is relatively easy to discover rotten eggs, decayed meat and vegetables, because these are betrayed by the odor. Milk, however, does not putrefy in the way eggs and meat do, and even the taste is apt to be misleading. Chemical and chiefly bacteriological tests are the only safe guides to the dectection of poor milk. For it must be remembered that fresh clean milk, which contains few bacteria and is safeguarded against their entrance, will not spoil for many weeks. It decomposed more or less rapidly in proportion to the numbers of bacteria present, and bacteria enter milk chiefly with dust, dirt and through the agency of flies. The problem then is to prevent bacteria as much as possible from gaining access to milk and this object can be attained only by scrupulous cleanliness.

The enormous mortality of infants is thought to be largely due to poor milk. In some localities a successful battle has been fought and is

being fought against poor milk in many instances with gratifying results. A reduction of infant mortality is usually noted when the public milk supply is improved. Laudable efforts are being made by health authorities in various cities in this country by introducing ordinances, forbidding the selling of milk derived from tuberculous cows, unless the milk is pasteurized. It will, however, require the intelligent and active support of consumers to make these efforts successful.

Milk is secreted from the mammary glands in a sterile condition, that is to say, germs are totally absent. When the milk is discharged from the glands and enters into the cistern—the large reservoir—of the udder, some bacteria gain access; these having invaded the udder from the outside through the teat duct, a small canal in the teats through which the milk is withdrawn. The number of germs entering here is relatively small, however. The large numbers usually found in market milk enter during the process of milking and are the result of multiplication during transportation and storage, unless the milk is kept at a temperature below 40° F. No matter how careful the milker may be, some germs are bound to enter. It is therefore necessary to cool the milk rapidly after milking and keep it cold until consumed. We have then to consider chiefly two points in the production and handling of milk, first cleanliness in all manipulations and cleanliness of all utensils, and second rapid cooling and storage or transportation at low temperatures.

Milk is the natural food for all mammals and each species of mammal produces a milk of such composition as is most suitable for the young of the species. The-composition of cat's milk differs from that of cows, dogs or man's. Some animals produce milk which contains ten times as much fat as is contained in cow's milk. Thus we find proper adaptation in nature of the only suitable food for young mammals. Again, the composition varies in individuals of the same species or race, and during the period of lactation. As the young grow older the concentration of the milk increases. When the calf begins to suck its mother's milk the milk is of thinner consistency than after the calf is several weeks old. It is evident from this fact that, when we substitute cow's milk for human milk as food for infants, the relative increase of milk components is not proportionate to the growth of the infant, but to the growth of the calf. It is, therefore, preferable to feed infants with mixed milk from a herd of cows rather than from an individual

cow. In a herd we have cows in various stages of lactation and the mixture of milk results in a uniform product, which can be modified if this is desired. Practical experience has proved that the composition of milk obtained from a herd runs nearly the same from day to day.

It is well known that there are differences in composition between cow's milk and human milk. In human milk there is more butter fat and more milksugar. The nitrogenous part, that is, the part which is necessary to replace the cells of the body and enable development to take a normal course, is about half the amount in human milk as compared with cow's milk. The quality of these components is also different in the two kinds of milk. The protein of cow's milk consists chiefly of two parts, one is casein, the other lactalbumin. The latter is more readily digested than the former, but is present in small proportion. Human milk contains less casein and more lactalbumin than cow's milk, and consequently is more suitable for the food of infants. The fat in human milk is more finely distributed than in cow's milk, which also enhances digestion. Jersey cows furnish milk with a fat content nearly the same as human milk, but the fat globules are larger, and therefore Jersey milk is not as suitable for infants as milk from Shorthorns or Holsteins. The latter breeds produce milk with less fat than Jersey cows, but the globules are smaller.

It is obvious that human milk is the only perfect food for infants. If it is necessary to find a substitute we must be careful to select milk from cows whose product comes as near to human milk as possible. Here again it must be emphasized that mixed milk from a herd consisting of cows of different breeds, and in different stages of lactation, is the best milk to use. It is true that infants can adapt themselves to the use of a different milk from the one designed for them by nature, and it is fortunate that this is so. Cow's milk is the only available substitute for human milk. In some countries goat's milk is used, but this offers no advantages, and some disadvantages. Mare's milk or ass's milk is nearer in composition to human milk than other milks, but is difficult to obtain. Cow's milk serves the purpose very well, if it is derived from a mixed herd and obtained under cleanly conditions.

The essential points in producing healthful milk are to observe cleanliness in the process and to cool the milk rapidly and keep it cold. The result of a tendency to comply with these demands has been the establishment of dairies where milk is produced on scientific principles. The cows must be fed with wholesome fodder, must be kept clean and be in perfect health. Tuberculosis is detected by the most rigid test known, the application of tuberculin. This method shows the presence

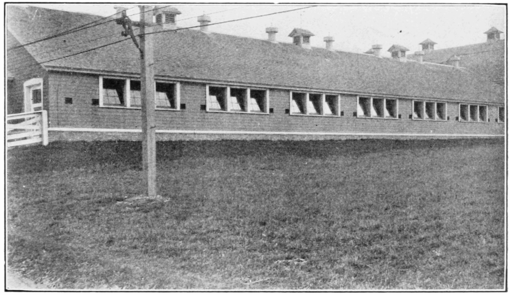

of tuberculosis even in initial stages. The stables are constructed with cement floors, with plenty of windows to admit light, and with effective designs for ventilation. Accompanying photographs, taken in model dairies, will illustrate the points under discussion. Photograph 1 shows one side of a sanitary barn with properly constructed windows, which open from the top and admit fresh air, and a carrier to remove the manure. A carrier of similar nature is used for bringing in the food, as shown in photograph 2. By the use of these carriers the handling of food and refuse is reduced to a minimum, and the raising of dust largely avoided. Photograph 3 shows stanchions of approved style, which allow the animals to be comfortable without being cumbersome. They are made of iron pipe, painted and easily kept clean. Photograph 4 shows the center aisle. The cows face each other to encourage cheerfulness. The mangers are also made of cement. Photograph 5 shows washstands, which should be present in all cow barns. The milkers wash their hands frequently so that the dirt from their hands is not mixed with the milk. The milkers should wear clean white suits, as is shown in photographs 6 and 7. The outlets of foul air and the tilting windows are shown to advantage in photograph 8.

In sanitary dairies the milk is transported to a special room in which it is cooled and bottled. In photograph 9 a cooling apparatus is seen above the collecting tank and on the left-hand side of the same picture is seen a machine which places the pulp caps on bottles.

Market milk contains hundreds of thousands of bacteria per cubic centimeter, sometimes even millions. When only such milk is obtainable it should be pasteurized. Pasteurization is a process by which milk is heated to 140° F. for thirty minutes. This treatment kills about

99 per cent, of all bacteria and makes the milk safe. Especially is pasteurization desirable when there is danger of disease germs entering the milk. Such disease germs may enter from the hands or clothes of employees in the dairy, also in certain cases from diseased cows. Pasteurization has many advocates and many opponents. Without going into a detailed discussion of the arguments, it may be stated that the process is gaining favor with sanitarians and recent scientific research has shown that the disadvantages claimed against pasteurization are groundless. Epidemics of typhoid fever, of dysentery, of diphtheria, of

scarlet fever have been spread by milk in many instances and we know with certainty that the germs causing these diseases are surely killed by efficient pasteurization. It remains with boards of health to control pasteurization, so as to insure its efficiency. For this purpose the milk should be examined before and after pasteurization. If the milk is obtained from careless producers, it should not be permitted to be used under any conditions. If the producer can show fair conditions the milk should be pasteurized.

If, however, milk is produced with the refinements outlined above, pasteurization becomes superfluous. Many dairies produce milk with less than 10,000 bacteria per cubic centimeter, some as low as 1,000. By extreme care and intelligent supervision such milk is not much more expensive than ordinary market milk and the outcome of the war waged against poor milk supplies will probably bring such milk within the reach of every one. This milk is generally known as certified milk, because it is certified to by a body of responsible medical men, who employ experts to examine the-milk at stated intervals and inspect the dairies, so as to insure safe methods of production. The conditions expected from the producer are rigorous, and consequently this certified milk costs more to produce than other milk. Unfortunately most of the dairies producing this excellent milk are heavily capitalized, but in some instances milk which is above reproach is produced at dairies with investments of $1,500 to $2,000. The essential point is efficient and constant supervision.

On the whole the solution of the problem of city milk supplies lies largely with the consumer. The consumer must be willing to pay a careful dairyman for his work and investment and when we remember that a quart of milk contains as much food, and readily assimilable food, as a pound of beef, and if we compare the cost of the two articles, we can not but admit that milk is a cheap food and a safe food if produced and marketed under proper precautions.