Popular Science Monthly/Volume 82/February 1913/The Progress of Science

Professor of Zoology, Columbia University, President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

THE CLEVELAND CONVOCATION WEEK MEETING

There was an excellent meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and of the affiliated national scientific societies at Cleveland during the week of January first. The scope and magnitude of their work can be indicated by a statement of the number of papers on the program for the different sciences, namely:

| Mathematics | 49 |

| Astronomy | 35 |

| Physics | 52 |

| Engineering | 40 |

| Geology | 27 |

| Zoology | 84 |

| Entomology | 73 |

| Botany | 60 |

| Phytopathology | 49 |

| Horticulture | 53 |

| Anthropology | 27 |

| Psychology | 56 |

| Biological chemistry and pharmacology | 63 |

| Anatomy | 63 |

| Physiology | 67 |

| Education | 11 |

| Economics and Sociology | 13 |

| Total | 822 |

In no other country except Germany could there have been brought together such an extensive series of papers nearly every one of which was based on research work and contributed to knowledge. Such a program demonstrates an extraordinary extension of scientific work in the United States in the course of the past twenty years. It may appear that men of great distinction and contributions of noteworthy importance were not represented in proportion to the total number of those who read papers. But this is in part due to the circumstance that one does not see the trees on account of the forest. If the only advances made in science during the past year were represented by a dozen of the papers taken at random from the Cleveland program, each one of them would appear to be an important scientific contribution.

It is noticeable that the different sciences represented on the program contributed papers not far from equal in number, even though the sciences themselves may vary greatly in importance and in the number of its workers. Fifty to seventy papers are about as many as can be presented in a three days' meeting, and most of the societies had about so many. Thus phytopathology was as largely represented as botany, entomology as zoology, physiology as physics. This seems to demonstrate the value of scientific organization, for if there had not been societies for the presentation of these papers, it may be that the work would never have been done.

There are several cases in which the program does not adequately represent the scientific work of the country. Thus the engineering societies do not meet with the association and the section of engineering is weakened. This year the chemists decided to meet separately like the engineers, partly because New Year's week, chosen as a time when college and university men can be present, is inconvenient for those engaged in industrial work. It seems desirable to increase rather than to decrease the contact of the pure and applied sciences, and it may be hoped that joint meetings may be arranged, perhaps at periods of three years. In that case the national societies devoted to economics, history and philology might also join in a great convocation  Dr. E. B. Van Vleck,

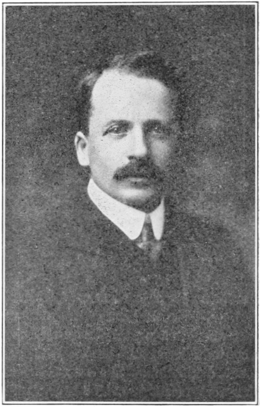

Dr. E. B. Van Vleck,

Professor of Mathematics at the University of Wisconsin, Vice-president for Mathematics and Astronomy. week meeting, which would impress on those present and on the public the magnitude and weight of the work being accomplished for science and scholarship.

The American Association for the Advancement of Science and its affiliated societies have failed to accomplish as much as the British Association for the diffusion of science and in bringing together those engaged in scientific research and those who are or might become interested.  Dr. William A. Locy,

Dr. William A. Locy,

Professor of Zoology at the Northwestern University, Vice-president for the Section of Zoology. Programs of general interest were arranged at Cleveland by nearly every section, but the attendance was practically confined to scientific men. Such meetings should be brought to general attention by full accounts  Dr. J. A. Holmes,

Dr. J. A. Holmes,

Director of the Bureau of Mines, Vice-president for the Section of Geology. in the local press and by reports throughout the country, but here almost complete failure must be confessed.

The council of the association took several steps intended to improve its  John Hays Hammond, LL.D.,

John Hays Hammond, LL.D.,

Vice-president of the Section of Social and Economic Science. organization. The members on the Pacific coast, who number about 500, were authorized to make arrangements for a general meeting at the time of the Panama Pacific Exposition of 1915, and if they see fit to hold annual sectional scientific meetings. All institutions engaged in scientific research were requested to send delegates to the convocation-week meetings, paying their expenses when possible. In addition to the permanent secretary and the assistant secretary there was  Dr. Duncan S. Johnson,

Dr. Duncan S. Johnson,

Professor of Botany at the Johns Hopkins University, Vice-president for the Section of Botany.

Dr. J. J. R. McLeod,

Dr. J. J. R. McLeod,

Professor of Physiology at the Western Reserve University, Vice-president for the Section of Physiology. made provision for an associate secretary, who shall devote his entire time to the association and to the organization of scientific men.

The high scientific standing of the men responsible for the conduct of the work of the association is shown by the officers annually elected. We are able to reproduce here portraits of several of those who presided over the sections at the Cleveland meeting. The president of the association, Professor Edward C. Pickering, director of the Harvard College Observatory, is able to transfer this high office to Professor E. B. Wilson, professor of zoology at Columbia University. So long as the association is able to select presidents such as these, it bears witness to the fact that this country possesses men who unite scientific genius with personal distinction. The next convocation-week meeting will be at Atlanta; two years hence Philadelphia is proposed.

AN EXTINCT SPECIES OF MAN

An anthropological discovery, rivalling in importance the discovery of Pithecanthropus erectus in Java by Dr. Du Bois twenty years ago, was communicated to the London Geological Society last month by Mr. Charles Dawson and Dr. A. S. Woodward, the keeper of the Geological Department of the British Museum. It appears

that some four years ago Mr. Dawson noticed that a road had been recently mended by peculiar flints, and on tracing them to their source, he found that the laborers had dug out an object looking like a cocoa-nut, which they had thrown on a rubbish heap. This proved to be part of a human skull, and excavations of the undisturbed gravel where it was found discovered part of the jaw bone. A somewhat absurd cablegram was sent the newspapers in this country reporting the discovery of a fossil man who could reason before he could speak. But it is the case that the cranium is on the whole human in its characteristics, while the jaw tends to be simian.

A restoration of the jaw by Dr. W. P. Pycraft, of the British Museum, is here given, and a more fanciful reconstruction of the primitive man, drawn under his direction by Mr. Forestier for the Illustrated London News. The remains were found on a plateau 80 feet above the river bed, to which extent denudation had taken place since the gravel was formed. In it were also found the remains of extinct mammals and many water-worn, iron-stained flint artifacts, to which the term eoliths has been applied. The gravel is early pleistocene, near enough to pliocene to make it almost certain that the immediate ancestors of the pleistocene man must have lived during that period.

The cranium is fragmentary, but typically human, with a capacity of over a thousand cubic centimeters, indicating a brain about four fifths that of the average European and twice as large as that of the highest apes. The. bones are remarkably thick and the temporal muscles extend higher up on the skull than in any recent or fossil man. The jaw bears some resemblance to the Heidelberg jaw, but it is less massive, with a still more negative chin and other simian features. As restored it is much like that of the chimpanzee. Dr. Woodward regards the remains as belonging not only to a hitherto unknown species, but has erected for it a new genus to which the name Eoanthropus dawsoni has been given. Recent discoveries prove that primitive man at a period from one hundred thousand to a million years ago was widely spread over Europe and apparently as far as Java, and that different species and perhaps genera may have lived simultaneously in different regions.

THE SEALS OF THE PRIBILOF ISLANDS

President Taft has sent a special message to the congress recommending the repeal of the law passed on February 15 of last year prohibiting the killing of seals on the Pribilof Islands for five years. His recommendation and that of the experts of the government should certainly be followed by the congress. A clear statement of the whole situation, drawn up by Dr. David Starr Jordan and Mr. G. A. Clark, has been recently given out by the Bureau of Fisheries of the Department of Commerce and Labor. The Pribilof Islands in Bering Sea came into the possession of the United States in 1867, and our government has received about ten million dollars in royalties paid on seal skins. At the time of the transfer to the United States, the herd numbered about two and a half million animals, but has now been reduced to about one tenth of that number. The decline was due to pelagic sealing which took advantage of the migration journeys and distant feeding habits of the seals to kill them in the open sea. In 1894 about 60,000 animals from the Pribilof herd were killed in this way, mostly females with unborn young or with pups in the rookeries. It is said, further, that from a half to three quarters of the seals shot in pelagic sealing are never recovered.

Many efforts were made to do away with the evils of pelagic sealing, and finally in 1911 a treaty was drawn up according to which the United States and Russia, as owners of the principal fur seal herds, agreed to pay to Great Britain and Japan fifteen per cent, each of the product of their land-sealing operations, on condition that pelagic sealing be abolished by those nations for fifteen years. If no seals are killed on the Pribilof Islands, the treaty would be practically made of no effect, and one might expect pelagic sealing to be resumed. It is also true that those best informed on the subject hold that the killing of superfluous bulls is a real advantage to the herd. The seal is a polygamous animal, each bull having an average family of fifty cows. Fear of the adult males causes the young males to herd by themselves, and they may be driven away and handled like cattle. If there are too many bulls, there is continuous fighting, and the pups are killed. The conditions are somewhat similar to those in the raising of cattle, the experts wishing to use the methods commonly in vogue, whereas the suspension of the killing of superfluous males would lead to the condition in which calves are being raised in a field in which there are a hundred cows and a hundred bulls.

It is certainly to be hoped that the congress will accept the recommendation of President Taft and its own experts and not interfere with the proper interpretation of the treaty of 1911 and the best treatment of the seal herd of the Pribilof Islands.

SCIENTIFIC ITEMS

We regret to record the death of Dr. Lewis Swift, formerly director of Mt. Lowe Observatory, known for his discoveries of comets and nebulæ; of Mr. Samuel Arthur Sanders, a British astronomer, and of Mr. William G. Tegetmeier, the English naturalist.

The national scientific societies at the recent convocation-week meetings elected presidents, as follows: the American Physical Society, Professor B. O. Peirce, of Harvard University; the Geological Society of America, Professor Eugene A. Smith, professor emeritus of the University of Alabama and state geologist; the Society of American Bacteriologists, Professor C. E.-A. Winslow, of the College of the City of New York; the American Botanical Society, Professor D. H. Campbell, of Stanford University; the American Anthropological Association, Professor Roland B. Dixon, of Harvard University; the American Psychological Association, Professor C. H. Warren, of Princeton University; the Society of the Sigma Xi, Professor J. McKeen Cattell, of Columbia University; the American Society of Naturalists, Professor Ross G. Harrison, of Yale University; the American Economic Association, Professor David I. Kinley, of the University of Illinois; the American Historical Association, Professor William A. Dunning, of Columbia University.

It has been proposed to municipal authorities of Paris that the memory of Henri Poincaré should be honored where he taught, and it is suggested that the portion of the Rue Vaugirard between the Boulevard St. Michel and the Odéon should be named after him.