Portland, Oregon: Its History and Builders/Volume 1/Chapter 10

CHAPTER X.

1843—1847.

With the establishment of the provisional government, the few scattered American settlers took heart and began to think that it was really safe to plant some permanent stakes with a view of remaining in Oregon as a permanent home. The Methodist missionaries had, it is true, prior to that time, made some settlement in the Willamette valley and at Oregon City. But such as it was, it could hardly have been at that time considered a permanent settlement, as the settlements at both places were subsequently moved to Salem.

The first settlement in the district covered by this history was made at Vancouver in 1825, by the Hudson's Bay Company. The next within this district was also by the Hudson's Bay Company at Oregon City, in 1829. In 1832, Dr. John McLoughlin, chief factor for the Hudson's Bay Company, blasted out and constructed a mill race to conduct the water from above the Willamette falls to a point below the waterfall, to be used in a mill to grind wheat into flour. This was the first work to start a business and manufacturing enterprise in this district. In 1838 McLoughlin had timbers cut and squared and hauled to the ground for the mill, and built a house at the "falls." Several families settled at the "falls" in 1841 and 1842, and in 1843 Dr. McLoughlin surveyed off a mile square of land, and platted the town of Oregon City. This was the first town in Oregon, and the original rival to Portland.

Another location for a city, made in some respects anterior to Oregon City, was that of Nathaniel J. Wyeth at the lower end of Sauvie's Island, known in 1835 as Wapato Island. Wyeth was an enterprising young business man of Boston with considerable capital, and had been induced to launch a great trading and colonizing scheme to Oregon by the writings of Hall J. Kelley. Wyeth arrived in Oregon in September, 1834, having left Fort Hall on August 6th with a party of thirty men, some Indian women and one hundred and sixteen horses. On reaching Fort Vancouver, with Jason Lee and others, the first Protestant religious services in Oregon or west of the Rocky mountains were celebrated. Wyeth took two of his scientific men in a small boat and started down the Columbia to find a good location to build a city. The party passed down and around Wapato Island, and finally decided to locate the future great city of the Pacific at the lower end of the island where his ship, the May Dacre, had tied up after reaching the Columbia and sailing up the river. This spot is just above where the government lighthouse on the lower end of the island is located. Here Wyeth assembled all his men, both from the overland party and from the ship, and all hands went to work laying the foundations of the city. A temporary storehouse was erected, the livestock was landed from the ship, and then the goods landed and stored. Ground was cleared, streets were laid out, and a row of huts built for quarters for the men; and the pigs, poultry, sheep and goats that had successfully made the trip from Boston, Mass., to old Oregon, were turned loose in the streets of "Fort William"—the name given by Wyeth to his great western city; and logs and boards were cut and sawed for permanent structures. Wyeth set up a cooper shop and set his coopers at work making barrels, into which he would pack the salmon they would catch in the Columbia to send back to Boston on the ship. And some salmon were caught, packed and actually shipped back to Boston. This was the beginning of the great salmon industry of the Columbia river, antedating Hume, Kinney, Cook and others, thirty-five or forty years—but it was the last of Wyeth's city—the ship got about half a cargo of fish under great difficulties; McLoughlin discouraged trading with Wyeth, as he was compelled to do by his company, and the whole scheme proved a failure. After the island was abandoned by Wyeth, the Hudson's Bay Company established a dairy down there under the care of a French Canadian named Jean Baptist Sauvie, which gave the modern name to the island and started the dairy industry where it has flourished ever since.

Another city was platted opposite Oregon City in 1843 by Robert Moore who came to Oregon from Pennsylvania. Moore named his city "Linn," in honor of Senator Linn of Missouri, the friend of Oregon. A few substantial buildings were erected on that side of the river and maintained a precarious existence until 1862, when they were all washed away by the great flood in the Willamette.

But Moore was not to enjoy a monopoly of townsite advantages opposite the original Falls City, for one, Hugh Burns, proceeded to lay out another city below that of Moore's, which he named Multnomah City, and commenced to build it up by starting a blacksmith shop and operating it himself.

Four years after Moore's venture, Lot Whitcomb, a man of push and enterprise from the state of Illinois, who built the first steamboat in Oregon, uniting with Seth Luelling, the founder of the fruit industry in Oregon, and Captain Joseph Kellogg, a prominent steamboat man of later days, united their capital and enterprise to build a city that should eclipse all others, and founded the town of Milwaukee—and which is still prospering.

And as we float down the Willamette in our townsite canoe, we come to the town of St. Johns, laid out in about 1850 by John Johns, where he erected and operated in a very quiet way, a country store for many years. But the tide of prosperity finally swung around to St. Johns, but not until after its founder had passed on to the city beyond this life, and now St. Johns is the most prosperous suburb of Portland.

And across the river, a little below St. Johns, we find the town of Linnton, which was planned and platted in 1844 by M. M. McCarver and Peter Burnett, both prominent in the provisional government. McCarver was a city builder, somewhat of the air-castle style. He was so sure that Linnton would be the great city of the Pacific coast that he declared the only thing in the way of that result would be the difficulty in getting enough nails to the townsite in good season. McCarver made nothing of Linnton; and then went over to Puget Sound, and along along with Pettygrove, one of the founders of Portland, laid out the city of Port Townsend, and early pulling up his stakes there, went to old Tacoma and made his final effort in city building.

Continuing on down the Willamette slough, our townsite canoe pulls up to the south bank of the river near the mouth of Milton creek, where we find the remains of a city started there in the year 1846 by Captain Nathaniel Crosby, and named "Milton." But whether the creek gave the name to the town or the town named the creek, Captain Crosby left no clue. It had a sawmill and a small population, and a convenient boat landing, but was finally overshadowed by the next city below—St. Helens—which was founded by Captain Knighton and others in 1845.It is not hard to understand the fact of so many townsite locations having been made in the vicinity of Portland. Everybody in the country in those pioneer days, could see as well as we can now, that there would be somewhere above the Columbia river bar, a town started which would grow into a great city, and make a fortune or fortunes for the lucky proprietors. Every man had his individual ideas of the proposition. The city would either be at Astoria, where Astor located, or it would be up near the mouth of the Willamette river. It would be wherever the ships cast anchor to discharge cargo. If they did not stop at Astoria, they would sail on up the river until they reached the outlet of the Willamette valley. And every man of much prominence was busily engaged in trying to find the favored spot. It was not even a question of buying the townsite. The whole country was open to location. The land was free. No one knew whether it would be English or American. But it did not cost any money to claim it if the true location could be determined. And so there were, counting in Portland, the ten locations we have named; and the result was a contest for the survival of the fittest; a purely evolutionary movement in commercial developments.

Every townsite proprietor had his unanswerable reasons why his town was the right place for the great city, but not one of them, except Hall J. Kelley, who has not been counted among the competitors, ever supposed there would be a town of more than twenty thousand people. The Oregon City lot holders with Dr. McLoughlin at their head, believed that the great water power for manufactures at that point, and the head of navigation for ocean vessels, would build the city at the falls. Moore and Burns argued that as their side of the river was the best place for the canal and locks and nearer to the Tualitin county farms by a ferry charge, therefore the city would be on the west side of the river opposite Oregon City. They guessed right as to the canal and locks, but missed on the farmers.

The Milwaukee owners claimed that Oregon City was not the head of navigation, because the Clackamas river had dumped a pile of gravel into the Willamette, that ships could not get over, although Captain Couch had once got his ship clear up to the falls on the June freshet. But the gravel argument did finally "sand-bag" the hopes of all the falls people on both sides of the river. But (illegible text) it shut out the two falls towns, it did not help out Milwaukee to any appreciable extent. Milwaukee had its day for several years, and then had to yield to Portland.

St. Johns and Linnton united to decry Portland as the head of navigation, just as Milwaukee had cried down the Willamette falls towns. They pointed out that Swan Island was an impossible barrier to ships from the ocean, and that while they could easily sail right in over the Columbia river bar, and right along up the Columbia to their towns, the ships could never do any business at Vancouver or Portland. And Linnton pointed with pride to the fact that it had three rivers to support its hopes and make sure its prosperity—the Columbia, the Willamette and Willamette slough.

Wyeth's townsite on the end of the nose of Sauvie's Island, was the first aspirant to the honor and profit of the great city; and also the first failure in the race for fame and prosperity. And for the reason that Dr. McLoughlin had apparently transferred all his hopes to Oregon City while still holding Vancouver as a vassal of the Hudson's Bay Company, and the occupier of the most beautiful townsite on the great river. Vancouver was thus practically shut out from any chance to grow as a trade center until after Portland got such a substantial foothold that its future could not be shaken. This left only Milton and St. Helens to contest supremacy with Portland's ambition.

It was soon shown that Milton, notwithstanding that it was boomed by a ship and a successful shipmaster, was too close to St. Helens ever to become a great city, just as Oregon City had conclusively shown that Portland was too close to Oregon City to ever achieve greatness. But St. Helens was the only town that ever gave Portland anything of a contest for the metropolis. Prior to the location of Portland, nearly all the ocean transportation came to and sailed from Vancouver, being almost wholly in the hands of the Hudson's Bay Company.

Lewis and Clark had given the world the idea that large ships could not come into the Willamette river. On their report to the president they say, speaking of what a great harbor the Columbia river might be: "That large sloops could come up as high as the tide water, and vessels of three hundred tons burden could reach the entrance of the Multnomah (Willamette) river." At that time (1806) the largest vessel afloat did not carry more than a thousand tons, but the thousand-ton vessel could have come to Portland townsite as easily as it got over the Columbia bar. But everybody understood then that it would be in the end the ocean transportation that would locate the city. To secure that was to secure the city. Captain Couch and others, with little sailing vessels, had worked their way up to Portland without tugboats to tow them, for there were no such helpers in those days. But that was not decisive. Would the ocean steamers come to Portland? That was put to the test when the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, the first proprietors of steamships regularly running to the Columbia river, bought a tract of land at St. Helens, erected a dock and warehouse and stopped all their steamers at that point. One of the most enterprising men in Oregon at that time, or even since, was Lot Whitcomb, who was energetically pushing the fortunes of his town of Milwaukee. He had town lots to sell; he soon had a steamboat; and he had a sawmill at Milwaukee that was making and shipping to the then mushroom gold diggers' town of San Francisco the very first lumber shipped from Oregon—and he was making a pile of money. And so he pushed his town. The steamship company was pushing St. Helens, and sending freight up the river in little boats of all sorts—and Portland was practically between the Whitcomb devil and the deep sea.

But Portland had some energetic men. The townsite proprietors, Stephen Coffin, W. W. Chapman and Daniel H. Lownsdale, were not only enterprising and energetic men, but they were able to see further into the future and make more of their opportunities than others. They saw their opportunity; the opportunity that is

"Master of human destinies;

Fame, Love and Fortune on my footsteps wait;

Cities and fields I walk; I penetrate deserts

And seas remote, and passing by

Hovel and mart and palace, soon or late,

I knock unbidden once at every gate."

And they lost no time in purchasing an ocean steamship that should ply between Portland and San Francisco. This vessel, the Gold Hunter, was kept on the San Francisco route until both Whitcomb of Milwaukee, and the Pacific Mail Steamship Company abandoned their opposition to Portland; the steamship company running all their ships to Portland, and Whitcomb running his steamboat from Portland to other points. It cost Coffin, Chapman and Lownsdale an immense sacrifice in town lots to purchase the Gold Hunter and run her until the contest was decided. But they were equal to the occasion, and if their successors in real estate holding and business at Portland had possessed one-tenth of the energy and public spirit of these founders of the city, Portland would have been larger today than all the Puget Sound towns and cities combined.

Two important facts combined to locate the principal city of the north Pacific coast at this point. The first in importance was that of a ship channel from the Pacific ocean to this townsite; the second point was the farmer's produce. Without that there would have been no city here. Fort William, St. Helens, St. Johns and Linnton each had the first advantage equally with Portland, but they were left behind in the race because they lacked the other advantage. The other point was equally vital when the race for commerce commenced, for no matter how many ships could come in over the Columbia bar and come up the river, they must have some cargo to carry away. And they could only get that at a point where the farmer could come with his produce, and it must be the shortest practicable haul between the farm and the ship; and Portland alone of all the other points offered that advantage. Portland alone of all the other points could complement the end of the ship channel with the shortest wagon haul to the farm and could thus halt the ship where the wagon unloaded. In these days of railroads wagon transportation would cut no figure. But in 1845, when the railroads had not even then reached the Alleghany mountains from Atlantic tide water, the city must be where the wagons and ships could meet. The scattered farmers of the Tualitin plains of Washington county, hauling in their produce and hauling out their supplies through the old Canyon road, was a mighty factor in locating Portland as the chief city. And it is a notable fact that for more than half a century the people of this city and the people of Washington county have always stood shoulder to shoulder in all enterprises to promote each other's welfare. When it was proposed to build railroads up the Willamette valley more than forty years ago, Portland gave its support to the road that was to run west into Washington county, and gave nothing to the road that was to run south along the Willamette river. And years ago Portland built superb macadam wagon roads out to the Washington county line, and would have gone further west with them if the county line could have been pushed back.

The commencement of a great work has always commanded unaffected interest. And how much greater the interest is the founding of a city or a nation. The semi-fabulous story of Romulus and Remus founding the city of Rome more than twenty-five hundred years ago, has enlisted the attention of young and old, children and philosophers for thousands of years. And every reader involuntarily goes back, or tries to get back to the man who started a great movement, performed a great deed or founded a city or state. So it is with all the readers of this book. They are wondering what manner of man it was that selected this site, backed up against the rock-ribbed hills that flank north and south from Council Crest, and look out upon the grandest panorama of forests, plains, valleys, rivers and mountains that can be found on the face of the earth. They are wondering if it was an accident, or did that man think it all out by himself, and come here and drive down the first stake for Portland, Oregon, in the midst of the mighty forests.

After the native red man, according to all reliable evidence, the first white man to come upon this townsite and say, "This is my land, here will I build my hut, here will I make my home," was William Overton, a young man from the state of Tennessee, who landed here from an Indian canoe in 1844, and claimed the land for his own. He had not cleared a rod square of land; he had not even a cedar bark shed to protect him from the "Oregon mist," when one day on the return trip from Vancouver to Oregon City, he invited his fellow passenger, A. L. Lovejoy, to step ashore with him and see his land claim, which he did. The two men landed at the bank of the river as near as could be located afterward, about where the foot of Washington street strikes the river, and scrambled up the bank as best they could, to find themselves in an unbroken forest—literally "the continuous woods, where rolls the Oregon." The only evidence of pre-occupation by any human being, was a camping place used by the Indians along the bank of the river, ranging from where Alder street strikes the water, up to Salmon street. This was a convenient spot for the Indian canoes to tie up at on their trips between Vancouver and Oregon City, and the brush had been cut away and burned up, leaving an open space of an acre or so.

On this occasion, Lovejoy and Overton made some examination of the land back from the river, finding the soil good and the tract suitable for settlement and cultivation if the dense growth of timber was removed. Overton was penniless and unable to pay even the trifling fees exacted by the provisional government for filing claims for land, or getting it surveyed, and then and there proposed to Lovejoy if he would advance the money to pay these expenses, he should have a half interest in the land claim—a mile square of land. Mr. Lovejoy had not exercised his right to take land, and the proposition appealed to him. Overton had not thought of a townsite use for the land and did not present that view of the subject. But the quick eye of Lovejoy took notice of the fact, that there was deep water in front of the land, and that ships had tied up at that shore, and so he accepted Overton's proposition at once, and became a half owner in the Overton land claim; and the Portland townsite proposition was born right then and there in the brain of Amos Lawrence Lovejoy; and making him in reality and fact the

"FOUNDER OF THE CITY OF PORTLAND."

Following up this bargain and joint tenancy in this piece of wild land, Lovejoy and Overton made preparations for surveying the tract, some clearing and the erection of a log cabin. But before these improvements could be even commenced, Overton's restless disposition led him to sell out his half interest in the land to Francis W. Pettygrove for the sum of fifty dollars to purchase an outfit to go back to the states or somewhere else, nobody ever knew where. Of Overton, nothing is known of the slightest consequence to the location of the town. One account says that he made shingles on the place. If he did, it was probably only for the cabin that was necessary to hold the claim, but he never built any sort of a house protection, and sold out to Pettygrove before the cabin was built. Overton was a mere bird of passage; no one ever knew where he came from or where he went to.

By some writers, Overton is given the honor of being the "first owner of the Portland land claim," and "after completing his settlement" he sold out to Lovejoy and Pettygrove. But he never was the owner of the claim, and he never made or completed any settlement. He had done nothing to entitle him to the land; he merely said to a passer-by, "This is my claim." He filed no claim with the provisional government, he posted no notice, he built no cabin, and he did not even do what the pioneers of the Ohio valley did, in a hostile Indian country in taking lands—he blazed no line or boundary trees. The Ohio valley pioneers took what was called in their day "tomahawk claims" to land. That is, they picked out a tract of land that suited their fancy, twoor three hundred acres, and then taking a light ax or Indian tomahawk, they established and marked a boundary line around the piece of land by blazing a line of forest trees all around that land. That was the custom of the country. There was no law for it. Those settlers were hundreds of miles beyond the jurisdiction of any state, or the surveillance of any government officer. But when the public surveys were extended west from Pennsylvania and Virginia, these "tomahawk claims" were found to cover large settlements. Their blazed trees were notice to everybody and were respected by all incoming settlers; and the United States government surveyors were instructed to adjust all these irregular boundary lines and give the actual settlers on the lands, or their bona fide assignees, accurate descriptions of these claims, which were in due course confirmed by government patents. The first settlers in Oregon, both British and American, were doing precisely the same thing to secure their homes and farms; and it was one of the objects of forming the provisional government to provide for the recording of all these claims to the end that strife and litigation might be prevented. The provisional government had already before Overton set up a verbal claim to the land provided for this registry of claims. Overton had not compiled with that law, but gave Lovejoy half of his inchoate right, whatever it might be, to go ahead and comply with the law, and which Lovejoy did. Lovejoy is then in truth and fact the founder of Portland, Oregon, for it was he who secured the title to the land for a townsite, and originated the townsite proposition.Amos L. Lovejoy was a native of Groton, Mass., a graduate of Amherst College, a relative of the prominent Lawrence family of the old bay state, studied law, read Hall Kelley's descriptions of Oregon, and started west. Making a halt in Missouri, he commenced the practice of law in that state. But falling in with Dr. Elijah White, who had been appointed some kind of an Indian agent for Oregon, Lovejoy crossed the plains and came to Oregon in 1842, with the party of Dr. White, and in which party he acted as one of the three scientific men to record all cheir experiences and discoveries on their journey through the wilderness. On reaching Oregon, Lovejoy fell in with the missionary, Dr. Marcus Whitman. And here we must record one of the most remarkable episodes in the pioneer settlement of this state. For no sooner had Lovejoy reached the Walla Walla valley than Whitman besought him to return to the states with him (Whitman) as a companion. Not one man in ten thousand, for love or money, would have undertaken that trip in the approaching winter, after just finishing a like trip from Missouri to Oregon. But he yielded to Whitman's entreaties, starting to the states in the month of November, and reaching Missouri in February, by the southern route through Santa Fe, Mexico, and suffering every imaginable trial, privation, danger and distress while living on dog meat, hedge-hogs, or anything else of animal life that would sustain their own lives. In May following his return to Missouri, Mr. Lovejoy joined the emigrant train of 1843, and again returned to Oregon, arriving at Fort Vancouver in October. He had thus made three trips across the western two-thirds of the continent, over six thousand miles in travel, on horseback altogether, suffering all the trials and dangers of the plains, being once taken prisoner by the Sioux Indians, and breaking all records in overland Oregon trail travel, in the space of seventeen months. And such was the courageous and determined character that founded Portland, Oregon.

In organizing and maintaining the provisional government, Mr. Lovejoy took a leading, useful and honorable part. He occupied first and last nearly every office in the government, and was elected supreme judge by the people, and was exercising the duties of that office when the United States finally extended its authority over the territory in 1849.

Francis W. Pettygrove, who joined Mr. Lovejoy in developing the Portland townsite, was born in Calais, Maine, in 1812; received a common school education in his native town, and engaged in business on his own account at an early age. At the age of thirty years, he accepted an ofifer to bring to Oregon, for an eastern mercantile house, a stock of general merchandise, suitable for this new country. Shipping the merchandise and accompanying the venture with his family on the bark Victoria, he reached the Columbia river by the way of the Sandwich Islands, transferring his merchandise at Honolulu from the Victoria to the bark Fama. This vessel discharged cargo at Vancouver, and Pettygrove had to employ a little schooner owned by the Hudson's Bay Company to carry the goods from Vancouver to Oregon City. After selling out this stock of merchandise, Pettygrove engaged in the fur trade, erected a warehouse at Oregon City, and was the first American to go into the grain trade, buying up the wheat from the French prairie farmers.

But to return to the townsite, we find that after buying out Overton, Lovejoy and Pettygrove employed a man to build a log house on their claim and clear a patch of land. The house was built; a picture of which may be found on another page, near the foot of the present Washington street. The next year, 1845, the land claim was surveyed out, and a portion of it laid off into lots, blocks and streets. That portion of the land between Front street and the river was not platted into lots and blocks, it being supposed at the time that it would be needed for public landings, docks, and wharves, like the custom in many of the towns and cities on rivers in the eastern states. But if such was the idea and intention of the land claimants, they failed to make such intentions known or effective at the time, and their failure to do so gave rise to much trouble, contention and litigation thereafter.

But it must strike every reader that it was a most singular proceeding, counting very largely on the lax ideas held by those pioneers on the subject of land titles, that these two men could take up a tract of land in the wilderness without a shadow of title from either the United States or Great Britain—the governments claiming title to the land—and proceed to sell and make deeds to the purchasers for gold dust, beaver money or beaver skins, as came in handy, and everything going "merry as a marriage bell." No abstract of title can be found that covers or explains these anomalies in the dealings of the pioneers town lot sellers; but it is proper to add that in assuming control of the country, congress approved of the land titles initiated by the provisional government.

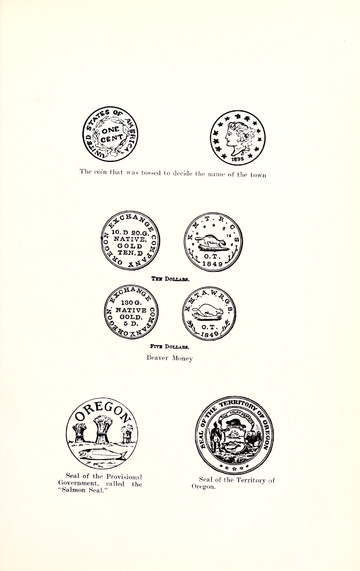

However, the real estate dealers in Portland in 1845, were giving a better deal to their customers in some things than their successors are in 1910. Nowadays the first thing in the history of a city is a grand map and a grander name. In 1845 Portland was started, and lots sold before it had any name. This proving somewhat awkward and embarrassing, the matter came up for discussion and decision at a family dinner party of the Lovejoys and Pettygroves at Oregon City. Mr. Pettygrove, hailing from Maine, wished to name the town for his favorite old home town of Portland, while General Lovejoy, coming from Massachusetts, desired to honor Boston with the name. And not being able to settle the matter with any good reason, it was proposed to decide the difference by tossing a copper; and so, on the production of an old-fashioned copper cent, an engraving of which is given on another page, the cent was tossed up three times and came down "tails up" twice for Portland, and once "heads up" for dear old Boston. And that is the way Portland got its appropriate name.

The town started slowly, and its rate of growth for the first three years was scarcely noticeable. Oregon City was the head center of all the Americans; the seat of government, the saw and the grist mill; and Vancouver did not invite and encourage settlers at that point. Men came and looked, and then passed on up the valley, or out into Tualitin plains and took land for farms. The people coming into the country were mostly farmers, had always been farmers, as had their forefathers, and had but little confidence in townsite opportunities. And besides all this, the lots offered for sale were so heavily covered with timber that it would cost more to clear a lot than the owner could sell it for after it was cleared; and so the town stood still or nearly so.

One of the first to start anything that looked like business at a cross roads or a townsite, was James Terwilliger, who erected a blacksmith shop and rang an anvil chorus for customers from the vasty woods all around. Terwilliger was born in New York in 1809; went west, following up the Indians, and came out to Oregon with the emigration of 1845. His shop at Portland was evidently only a side issue with him, running it only five years; for he at the same time took up a land claim a mile south of Lovejoy and Pettygrove, improved it, and there passed the remainder of his life, passing away in the year 1892 at The coin that was tossed to decide the name of the town

Ten Dollars.

Five Dollars.

Beaver Money}}

Seal of the Provisional Government, called the "Salmon Seal."

Seal of the Territory of Oregon. the advanced age of 82 years. James Terwilliger was always an active man of affairs, stoutly defending his opinions of the right, and with true public spirit, contributing to the improvement of the town and the development of the country.

Pettygrove erected a building for a store and put in a very small stock from his remnants at Oregon City. The business of the town moved imperceptibly; in fact there was no business worth mentioning. When a ship would come in, all that had money, furs, or wheat, would buy of the ship, and trade in their produce, so that merchandise at the store was a mere pretense.

The first item of improvement that so attracted the attention of the country as to have Portland talked about, was the starting of a tannery by Daniel H. Lownsdale. This was the first tannery north of Mexico in all the country west of the Rocky mountains. As a matter of fact, many of the farmers up in the valley had been tanning deer and calfskins in a limited way, as nearly all the pioneer people knew something of the art of tanning skins. But the Lownsdale tannery was started as a business enterprise to accommodate the public and make profit to its proprietor. Hides would be tanned for so much cash, or leather would be traded for hides; or leather would be sold for cash, furs or wheat. Here was a start in a productive manufacturing business, and Lownsdale's tannery was the talk of the whole country, and advertised Portland quite as much as it did the tannery. This tannery was not started on the townsite, but away back in the forest a mile from the river, on the spot now occupied by the "Multnomah field" of the Athletic Association. After running the tannery for two years, Lownsdale sold it to two newcomers—Ebson and Ballance—who in turn sold it to A. N. King, who then took up the mile square of land adjoining Portland on the west, known as the King Donation Claim, and which has made fortunes for all his children by the sale of town lots. Amos N. King was not much of a town lot speculator. It was a long time before he could muster up courage enough to ask a big price for a little piece of ground. He stuck to his tannery, and made honest leather for more than twenty years before he platted an addition to the city.

A leading citizen of those early days of Portland was John Waymire, who built the first double log cabin, and made some effort to accommodate strangers and traders who dropped off the passing batteaux to look at the new city, by furnishing meals and giving them a hospitable place to spread their blankets for the night. Waymire further enlarged his fortunes by going into the transportation business with a pair of oxen he had driven two thousand miles all the way from old Missouri, across the mountains and plains. As the new town was the nearest spot to Oregon City where the ships could safely tie up to the shore and discharge cargo, Waymire got business both ways. With his oxen he could haul the goods up to his big cabin for safety, and then with his oxen he could haul the stuff back to the river to load into small boats and lighters for transportation to Oregon City. In addition to the transfer business, and the hotel business, Waymire started a sawmill on Front street. The machinery outfit would not compare well with the big mills along the river in Portland at the present time, being only an old whip-saw brought all the way from Missouri, where it had been used in building up that state. The motive power being one man standing on top of the log, pulling the saw up preparatory for the down stroke, and another man in the pit under the log who pulled the saw down and got the benefit of all the sawdust. Waymire was the one busy man in the new town, and prospered from the start. He knew well how to turn an honest penny in the face of severe financial troubles. With the money made in Portland he went up to Dallas, in Polk county, in later years and started a store, thinking it safer to rely on the farmers for prosperity than takes chances on such a strenuous city life. There he sold goods "on tick" (credit), as was the custom of the country, and not being a good bookkeeper, he wrote down on the inside board walls of his store with a piece of chalk the names of his customers, and under each name the goods they had bought on credit, with the sums due. And while absent for a brief trip to Portland, his good wife, thinking to tidy up the store, got some lime and whitewashed the inside of the whole establishment. On his return and seeing what had been done, he threw up his hands in despair and declared he was a ruined man. The good woman consoled him with the suggestion that he could remember all the accounts and simply write them all over again on the wall. And so the next day being Sunday, and a good day, and everybody absent at church, he undertook the task. His wife dropped in after divine service, and inquired how he was getting along. He replied, "Well, I've got the accounts all down on the wall agin; I don't know that I've got them agin just the same men, but I believe I've got them agin a lot of fellows better able to pay." There were preachers and teachers and all sorts of men in Oregon then, as now.

Another man that dropped in on young Portland the next year after Waymire, was William H. Bennett (Bill Bennett) who, having quit the mountains and the fur trade, started in to make his fortune in making shingles out of the cedar timber on the townsite, which was a gift to him. Bennett got a start and prospered until he was ruined by his convivial habits. He pushed various small enterprises, finally starting a livery stable at the corner where the Mulkey block is now located. The business started by Bennett was owned successively by John S. White, Lew Goddard, Elijah Corbett, P. J. Mann (founder of the Old Folks' Home), Goddard & Frazier, and now by William Frazier at the corner of Fifth and Taylor streets. In 1846 came Job McNamee from Ohio, having come into the valley with the emigration of 1845. McNamee was a good citizen and brought a good family, wife and daughter, possibly among the first ladies of the place, and whose presence smothered down some of the rough places in the village. Mrs. McNamee became the wife of E. J. Northrup, one of the best citizens Portland ever had, and the founder of the great wholesale and retail hardware store now owned by "The Honeyman Hardware Company." Not long after the advent of the McNamees, came Dr. Ralph Wilcox from New York, a pioneer of 1845. Dr. Wilcox was the first physician and the first school teacher of this city, and a most useful and public-spirited citizen, taking a leading part in organizing society and serving the public as clerk of the state legislature and as clerk of the United States district and circuit courts. His widow, Mrs. Julia Wilcox, now over ninety years of age, is still active and an interested spectator of the growth of a city of two hundred and twenty-five thousand people, which she came to in her early womanhood as a few log cabins in an unbroken forest.

And about the same time as Dr. Wilcox came, came the O'Bryant brothers, Humphrey and Hugh, the latter of which became the first mayor of the city in 185 1, a notice of whom will appear with that of the other mayors. And about the same time with O'Bryant came in J. L. Morrison, a Scotchman, who set up a little store at the foot of Morrison street, giving his name to the street, and dealing in flour, feed and shingles.

L. B. Hastings and family came across the plains in 1847 and stopped a while in Portland. He is remembered as an active pushing business man, and stayed with the fortunes of the town for four years. But imagining he could see a larger city at the entrance to Puget sound, joined with Pettygrove in building a schooner, and loading it up with all their worldly belongings. Pettygrove sold out his interests in Portland, and the whole party sailed away in 1851, for Puget sound, where they founded the city of Port Townsend, and where they spent the remainder of their lives and strength in building up a city to eclipse Portland. Port Townsend has about two thousand population today, and Portland has twenty-five times as many, a clear proof that a man's backsight is always better than his foresight.

And now Portland got its first politician and statesman in Col. William King, landing on the river front in 1848. Col. King was an unusual man. He would have been a man of mark in any community. He was needed by the new city, and he made his presence felt from his very first day in town. Nobody seemed to know from what corner of the earth King came, and he took no pains to enlighten them. But he was a valuable addition to the city, as he was familiar with all sorts of scheming, and by that early day the new town had to look out for its interests at every session of the legislature; and King was always on hand to see that there was a square deal with possibly something over to Portland.

King made enemies as well as friends. His positive disposition and his love of fair play did not always tally with predisposed politics. It is remembered that at the time Governor Curry had selected officials for the militia without respect to party affiliations, a petition was gotten up by some democrats to have the whigs (republicans) removed or their appointments canceled. When it was presented to King to sign, he read it over carefully, then as if not understanding it, read it a second time, and then vehemently tore the document to pieces, and proceeded to denounce the authors in words more forcible than polite: "that such men would rather see women and children slaughtered by the Indians than to have a good man of the opposite party hold an honorable position in the militia."

As great nations have been dependent on the sea, not only for their prosperity, but also their very existence—England for example—so it was with Portland, Oregon, in the years 1845 to 1851. And now the story turns from the land builders of the town to the hardy sea rovers working to the same end. And in this good work the name of Captain John H. Couch stands at the top of the list.

The first appearance of Captain Couch in Oregon waters is in 1840, when he came out here from Newburyport, Mass., in command of the ship Maryland to establish a salmon fishery on the Columbia. The ship belonged to the wealthy .firm of the Cushings of Newburyport, who had been induced to some extent by letters from Jason Lee to make this venture. The fishery was not successful, for there was no fishermen but the Indians, and they were not reliable to serve the Americans. And so Couch sold the vessel at the Sandwich islands and returned to Newburyport, leaving in Oregon, George W. Le Breton, an active and pushing young man, who made his mark in helping organize the provisional government. Having learned from this voyage, the conditions and requirements of trade in Oregon, Couch returned in 1842, with a stock of good? in a new brig—the Chenamus—named for the Chinook Indian chief who had lived opposite Astoria; and leaving this stock at Oregon City with one Albert E. Wilson, who also came out in the Chenamus, and Le Breton, Couch engaged his vessel in the trade to the Sandwich islands, the whole business being under the name and auspices of Gushing & Company, of Newburyport. Couch continued to manage this business until 1847, when he returned home to Newburyport by the way of China. In the following year he engaged with a company of New York merchants to take a cargo of goods to Oregon on the bark Madonna, Captain George H. Flanders coming out with the Madonna as first officer, and took command of the Madonna on reaching Oregon, while Couch took charge of the cargo, which was stored and sold at the new town of Portland on the Willamette. The two captains went into business together, and remained in Portland for the rest of their lives. And thus were two of the best men located in Portland that ever lived in the state.

Portland got the benefit of all this shipping by Captain Couch. He early saw and fully appreciated the advantages of the location for the foundation of a seaport and commercial city, and took advantage of his opportunities to locate a land claim at what has long been the north end of the city. And considering what Captain Couch did directly for the town, by making it the home port of his ships for several years, and also what he did indirectly by influencing other vessels to tie up at Portland, he probably exerted more influence to give Portland a start than all other persons combined.

Next after Couch, in giving Portland a start, comes Captain Nathaniel Crosby, who founded the town of Milton, near the mouth of the Willamette slough. Crosby brought the bark Toulon into the river in 1845, and unloaded his vessel on the river bank at the foot of Washington street, and from there transported his goods up to Oregon City by smaller craft. Captain Crosby made numerous trips, and finally anchored in Portland and erected the first palatial residence in the new city — the old story-and-a-half house with dormer windows which stood for so many years on the east side of Fourth street, be- tween Yamhill and Taylor, having been removed to that site from its original location on Second street. To accommodate the increasing traffic of his ship- ping, Crosby erected a small storehouse on the city front, probably on the open strip east of Front street, but most of his merchandise was sent up to Oregon City, which continued to be the commercial center of the whole country.

Besides Couch and Crosby, there were other traders with ships entering the river. In 1847 Captain Roland Ghelston of New York, brought in the bark Whitton loaded with merchandise, and Captain Kilbourn came in with the brig Henry, also loaded with merchandise, and tied up at the east side opposite Port- land, and seriously threatened to start a rival city over there. There was plenty of free land to be had for the taking, and a townsite or two, more or less, could not make much difference to Portland ; and the doughty captain was told to go ahead with his town, for it would all be Portland after awhile — and so now, sixty-three years afterward, it is all Portland, with four bridges to connect the two sides and another bridge coming.

Captain Ghelston, mentioned above, made a second voyage to the Pacific coast, arriving in San Francisco bay just after the great gold fever excitement got well started. And taking advantage of the gold panic news sent to the states, Ghelston had laid in a heavy stock of picks, shovels and gold pans, and when he got safe within the "golden gate," his fortune was made from the sales of his hardware at prices twenty fold of what it had cost him.

With these ships came in some good men, who located, drove down their stakes, and stayed with the town until all got rich and repaid the town by great service as good and useful citizens. Of these may be mentioned Benjamin Stark, who came as supercargo on the Toulon ; Richard Hoyt, who came as first officer on the Whitton; and Daniel Lunt, one of the mates of the Chena- mus. Lunt took up a land claim south of that of Terwilliger's, and subse- quently sold it to Thomas Stevens. The suburb of Fulton is now built on the Lunt claim.

But according to the recollection of Col. Nesmith, the first land claimed within the present Hmits of the city, was the claim just south of that of Love- joy and Pettygrove. This was taken up in 1842 by William Johnson, an Eng- lish sailor, who was living on his claim before Overton was claiming the land he sold to Lovejoy and Pettygrove. Johnson's name figured considerably in the history of the celebrated or notorious "Wrestling Joe" Thomas' lawsuit about the Caruthers estate, that estate being almost wholly the land originally claimed by Johnson and abandoned or sold by him to Finice Caruthers. Mrs. Charlotte Moffett Cartwright remembers well the cabin of Johnson and his half blood Indian wife, which was located near the trail which led from the Terwilliger home to the "town." Johnson dropped out of sight soon after Ca- ruthers came into the country, and nobody ever knew what became of him.

Johnson had an interesting history, showing what a lot of odd and cele- brated characters drifted into this then out-of-the-way corner of the world. He was originally an English sailor, subject of Great Britain, but forswore his allegiance to the British king, and took service with the United States on the old frigate Constitution, and was in the celebrated naval battle between that ship and the British man-of-war Guerriere, in which bloody battle he made one of boarding party charging the bulwarks of the Briton and received an ugly scalp wound from a British cutlass. He delighted to tell of this terrible Tea fight speaking of the "Old Ironsides" as one might speak of their dearest friend. And being the only Oregonian known to have taken part in a naval battle m defense of the American flag, he is entitled to have his name reverently preserved in this history. When the war of 1812 broke out between the United Mates and Great Britain, it was supposed that as this country had no navy the English would sweep American merchantmen from the seas. This they tried to do; and the few small frigates of the Americans could offer but little opposition. The American ship made famous by the battle here commemorated, had but then recently returned from European waters, where she barely escaped capture by the speed of her sailing. And when she fell in with the British cruiser Guernere off the coast of Massachusetts on the 19th day of August, 1812, a trial of metal and nerve was the result. The British captain had been anxious to encounter a "Yankee man-of-war," having no doubt of an easy victory, and the "Yankee" Captain Hull of the Constitution was ready to accommodate him. It was none of the modern steel-clad battleships firing- at each other from a range of eight or ten miles, but they were wooden ships and they sailed right into each other, firing their little cannon as rapidly as they could be loaded, until with grappling irons, one ship laid hold of the other and her brave men leaped over all obstructions to end the fight at arms length m a life and death struggle on the decks of the boarded ship. This was the real battle in which William Johnson, who had his little log cabin on the present site of this city out near John Montag's stove foundry, sixty-seven years ago, immortalized himself in. He was defending his adopted country against the injustice of the land that gave him birth, and he shed his blood that the stars and stripes should not be hauled down in defeat. He was the first settler on_ the site of Portland, Oregon. He was a member of the first committee appointed to organize a provisional government, and he was one of the fifty-two who stood up at Champoeg sixty-seven years ago to be counted for the stars and stripes. And it is justly due to his memory that his name and his great services be here duly recorded, that they may be honored for all time.