Provincial Geographies of India/Volume 4/Chapter 19

CHAPTER XIX

CHIEF TOWNS

Lower Burma

Rangoon. Rangoon is still the capital of Burma and the headquarters of the Local Government. Although it is only since the British conquest of Pegu that the city has risen to great importance, it was long a place of some note[1]. The dawn of its history is in the year 585 B.C., when the first Shwe Dagon Pagoda was built, and round it sprang up a village or small town. It was not till 1755 A.D. that it acquired its present name. In that year Alaungpaya laid out a new town on the river bank and called it Yan-gôn, the end of strife. Not long after, the East India Company established a factory and 1796 saw the appointment of a British Resident or Agent. At the time of Captain Symes' visit in 1794, Rangoon was a busy trading port, with some twenty-five to thirty thousand inhabitants, extending for about a mile along the river and about a third of a mile in depth. Inland, the square city (myo), characteristic of Burmese royal towns, was enclosed by a wooden stockade. The houses were raised from the ground on posts, some of bamboo, some of wood. Pigs roamed the streets and acted as scavengers. The description is strangely familiar to those who saw Mandalay in 1885. Later on, the town languished, probably on account of Burmese misrule, and in 1826 its population had dwindled to about 8000. It was a miserable place in a dismal swamp. After the First Burmese War, it began to revive. In 1841, King Tharrawaddy built a new stockaded city near the great Pagoda, and part of the town was transferred to the new site. By the time of the Second War (1852), the town was about as populous as in 1794. After the annexation of Pegu, it was laid out by Colonel Fraser on a definite and well-conceived plan allowing for further expansion.

The present city stands on the Rangoon River, twenty- one miles from the sea. It is the fourth town in India, in point of population. In the last thirty or forty years, it has entirely changed its character. In 1881 the population was 134,176, the larger proportion consisting of Buddhists. In 1911 the inhabitants numbered 293,316, of whom 108,350 were Hindus, 97,467 Buddhists, and 54,634 Mahomedans. In 1921 the population had increased to 341,962. Rangoon is now a cosmopolitan city, full of men of strange races and many tongues. The business part of the town lies along the north side of the river, stretching from Kemmendine and Alon on the west to Pazundaung on the east. Here are great rice mills, timber and oil depots, warehouses of imported goods, wharves and jetties, banks, shops, printing presses, offices. On the opposite bank is the busy industrial suburb of Dalla, a place of note before Rangoon was founded. The prosperity of Rangoon is mainly due to British, and, to a minor extent, Indian, commercial enterprise. The Burmese have had no part in it. The principal public buildings, the Secretariat, the Law Courts, the General Hospital, the Railway Station, are all worthy of the great city which they adorn. The Jail, alas! is one of the most populous in the world. Among buildings deserving special mention is the Roman Catholic cathedral, designed and built by a priest who was an architect and builder of taste and skill. Less conspicuous, but still of sufficient dignity, is the Anglican cathedral.

On the only eminence in or near Rangoon, on a spacious platform, rises the golden splendour of the Shwe Dagon Pagoda, famous among Buddhist shrines, covering relics of the four last Buddhas, the filter or water-strainer of Krakuchanda, the staff of Kāsyapa, the bathing-robe of Konāgāmana, and eight hairs of Gaudama. Fitch (1586) describes it in glowing words:

It...is of a wonderful bigness, and all gilded from the foot to the top. And there is a house by it wherein the tallipoies, which are their priests, do preach. The house is five and fifty paces in length and has three pawnes, or walks in it, and forty great pillars, gilded, which stand between the walks; and it is

open on all sides with a number of small pillars, which be likewise gilded. It is gilded with gold within and without. There are houses very fair round about for the pilgrims to lie in, and many goodly houses for the tallipoies to preach in, which are full of images, both of men and women, which are all gilded over with gold. It is the fairest place, as I suppose, that is in the world: it standeth very high, and there are four ways to it, which are all along set with trees of fruits, in such wise that a man may go in shade about two miles in length. And when their feast day is, a man can hardly pass, by water or by land, for the great press of people; for they come from all places of the Kingdom of Pegu thither at their feast[2].The Pagoda consists of a solid mass of brickwork, 312 feet in height from the platform. A great part of the fabric is covered with gold plates renewed from time to time. The whole is crowned by a ti, a metal framework studded with jewels, presented by King Mindôn in 1871. The platform

is crowded with smaller pagodas, zayats (rest-houses), tagundaing (poles adorned with streamers), subsidiary shrines, and other sacred buildings. Here is a great bell which the British essayed to remove by sea after the Second War. Unluckily, while it was being shipped, it fell into the river and all the king's horses and all the king's men failed to get it up again. In reply to their request, the Burmese were told contemptuously that, if they could recover it, they might keep it. So they took a bit of bamboo and fished up the bell and replaced it on the pagoda platform where it still hangs. If you take the deer's horn which lies handy for the purpose, first strike the earth, then strike the bell three times, your wish shall be granted. Approached by a long flight of steps, fringed on either side by rows of stalls where cheroots, toys, candles, and many varieties of miscellaneous goods, are offered for sale, the Pagoda attracts pilgrims and worshippers from all parts of the Province and sigh-seers from distant lands. Any day, one may see pious men and women telling their beads and murmuring their aspirations, acknowledging the misery of this transitory life, burning candles before holy images. As in Fitch's time, on sabbaths and feast days, the platform is crowded with Burmans of all ages, clad in gay silks of many colours, in the best possible temper. The Pagoda is in the custody of trustees who receive the offerings of the faithful and ensure the maintenance in good order of the shrine and its precincts. In too close proximity is an arsenal.

On the border of the city, approximately on the site of King Tharrawaddy's myo, lies the cantonment, a wide expanse, including the pagoda, where there are barracks, parade grounds, residences of military and civil officers. Formerly open and picturesque, it is gradually becoming crowded with houses. Presently it will be removed to a distance and the space will be given up to the expansion of the town. On its outskirts, in a well-wooded park, stands Government House, a building of some pretension. Beyond the cantonment lie the Royal Lakes, surrounded by Dalhousie Park, a worthy memorial of the great Governor-General who dedicated it to public use for ever. Nature, skilfully aided by art, has made of its sloping lawns, fairy glades, and winding paths, adorned with flowers in gay and gallant profusion, a scene of almost incomparable beauty.

Rangoon is administered as a separate district. Local affairs are managed by the Municipal Corporation of the City of Rangoon, constituted in 1922 by an elaborate Act recently passed. The Corporation at present consists of 34 Councillors, the maximum number being 40. Of the Councillors, 29 are elected, the rest nominated by the Local Government. Ten are elected by the Burmese community; five by Europeans; four each by Mahomedans and Hindus; two by Chinese; one each by the Port Commissioners, the Chamber of Commerce, the Trades Association, and the Development Trust. The Corporation elects its own President and appoints as its Chief Executive Officer a Commissioner who may be a Government servant. Subject to slight control by the Local Government, the Corporation is empowered to deal exhaustively with all details of municipal administration. The municipal income is about half a million sterling. The town and cantonment are lit by electric light and there is an ample water supply.

One Deputy Commissioner is District Magistrate and controls the administration of criminal justice; a second is Collector. The police of the city is administered by a Commissioner, directly responsible to the Local Government. The rank and file of the police are mostly Indians; but there is a sprinkling of Burmans as well as a small but effective body of mounted European sergeants and constables. The city of Rangoon constitutes a Sessions Division wherein the Chief Court exercises jurisdiction. Trials before the Chief Court are held with the aid of juries, Rangoon and Moulmein, being, except as regards European British subjects, the only places in Burma where the jury system prevails. Large projects for the development of the town are in contemplation. The Rangoon Development Trust, constituted for this purpose, came into being in February, 1921.

Rangoon is the third port in the Indian Empire, surpassed in volume of trade only by Calcutta and Bombay. "Nature has liberally done her part to render Rangoon the most flourishing sea-port of the Eastern world[3]." Much progress has been made in recent years. The whole of the import trade is now conducted alongside modern deep-water wharves lighted by electricity and equipped with hydraulic cranes and spacious sheds. Extensive accommodation has been provided for the inland vessels trade, and the mooring accommodation has been doubled. Some years ago, the existence of the port was in imminent danger. The deep-water channel above Rangoon was being diverted further away from the foreshore on the left bank of the river on which Rangoon stands. At the same time, extensive erosion of the river bed on the left bank threatened to undermine the wharves and jetties. It was decided to build a training wall, two miles long, to force the river back to its former course. This important work was completed early in the year 1914, at the cost of £920,000[4]. The wall is constructed of rubble stone deposited on a foundation of brushwood mattresses; the top consists of slabs of reinforced concrete[5]. The scheme appears to be completely successful.

A project of building an entirely new port at Dawbôn, below the Pazundaung creek, is under consideration. One advantage will be the avoidance of the Hastings shoal, at present a serious impediment to the entrance of the harbour. The new port, if established, will be equipped with docks for which no room can be found in existing circumstances.

In 1921—22, the total value of the sea-borne trade amounted to £89,000,000; to which exports contributed £53,000,000 and imports £36,000,000. The affairs of the port are administered by a Board of Commissioners, most of the members being ex-officio or nominated by Government. In 1919—20, the revenue of the port was £523,049, the expenditure £449,593. There was a debt of £2,986,200. Moulmein. Moulmein (61,301)[6], a port of some note, is the oldest British town in Burma, having been established as divisional headquarters in 1827. Situated on the Salween, twenty-eight miles from the sea, within sight of the junction of that river with the Gyaing and Ataran, it commands views of romantic beauty, unsurpassed for picturesque effect[7]. On the ridge above the town are two famous pagodas, Kyaikthanlan (875 A.D.), Uzima or Kyaikpadaw, said to have been built by Asoka. These are celebrated not only for their sanctity but also for the incomparable landscape spread out beneath them. Near Moulmein are well-known caves, haunted by innumerable bats. Commercially and economically, except as the depot of a large timber trade, Moulmein is not of great importance.Bassein. Bassein (42,503), known to early writers sometimes as Cosmin, sometimes as Persaim, on both sides of the Bassein river, some 60 miles from the sea, is a flourishing port. It was early the seat of a British commercial factory. A centre of the rice trade of the Irrawaddy Delta, it has many rice mills. Bassein is connected with Rangoon by rail, the Irrawaddy being crossed by a ferry at Henzada; and also by a line of river steamers plying through the creeks.

Akyab. Akyab (36,569), the fourth port, is the chief town, and the only town of any size, in the Arakan Division. Built on an island in the Bay of Bengal, in very picturesque surroundings, with an excellent harbour, it is a place of note. Its importance will be greatly enhanced when, in due course, it is connected with India by rail.

Prome. Prome (26,067) stands on the Irrawaddy 161 miles from Rangoon, the northern terminus of the first railway built in Burma. Before the annexation of Upper Burma it was a station on the quickest route to Mandalay. In mediaeval times the capital of a kingdom and the scene of many conflicts, it is now only an ordinary provincial town. It has two famous pagodas, Shwesandaw and Shwenattaung. Among the many bells on the platform of Shwesandaw is a beautiful specimen removed by General Godwin in 1852 and after nearly seventy years restored in 1920 by his grandson, Colonel H. H. Godwin-Austen, F.R.S.[8]

Tavoy. Tavoy (27,480), in the Tenasserim Division, on the Tavoy river, is one of the minor ports and the headquarters of a district.

Henzada. Henzada (23,651) on the Irrawaddy is a country town connected with Bassein by rail and with Rangoon by combined river and rail.

Toungoo. Toungoo (19,332), on the Sittaing river, 166 miles from Rangoon, is famous as the early capital of the conqueror, Tabin Shweti. Before the annexation, it was a place of arms on the frontier; and before the building of the railway it was quite remote, the journey to Rangoon occupying many days.

Pegu. Pegu (18,769), on the Pegu river, 47 miles from Rangoon on the railway to Martaban, is a somewhat melancholy relic of ancient splendour. In 1569, in the time of the great King Bayin Naung, it is thus described by Cæsar Frederick:

By the help of God we came safe to Pegu, which are two cities, the old and the new: in the old city are the Merchant strangers, and Merchants of the country, for there are the greatest doings and the greatest trade. This City is not very great, but it hath very great suburbs. Their houses be made with canes and covered with leaves, or with straw; but the Merchants have all one House or Magason, which house they call godon[9], which is made of brickes, and there they put all their goods of any value, to save them from the often mischances that happen to houses made of such stuff. In the new City is the Palace of the King, and his abiding-place with all his barons and nobles and other gentlemen; and in the time I was there they finished building the new city: it is a great City very plain and flat, and four square, walled round about, and with ditches that compass the walls about with water, in which ditches are many Crocodiles. It hath no Drawbridges, yet it hath twenty gates, five for every square; on the walls there are many places made for Sentinels to watch, made of wood, and covered or gilt with gold. The streets thereof are the fairest that I have seen, they are as straight as a line from one gate to another, and standing at one gate you may discern the other, and they are as broad as ten or twelve men may ride abreast in them: and those streets that be thwart are fair and large; these streets both on the one side and the other are planted at the doors of the houses with nut-trees of India, which make a very commodious shadow: the houses be made of wood, and covered with a kind of tiles in form of cups, very necessary for their use. The King's Palace is in the middle of the city, made in form of a walled castle with ditches full of water round about it; the lodgings within are made of wood all over gilded, with fine pinnacles, and very costly work, covered with plates of gold. Truly it may be a King's house: within the gate there is a fair large Court, from the one side to the other wherein there are made places for the strongest and stoutest elephants appointed for the service of the King's person, and amongst all other elephants he has four that be white, a thing so rare that a man shall hardly find another King that has any such, and if the King know that any other hath white elephants, he sendeth for them as for a gift[10].Now Pegu is a small provincial town, chiefly interesting on account of its rich treasures of Buddhist antiquities. Conspicuous are the beautiful Shwemawdaw Pagoda, 324 feet in height, dating from the 6th century, vividly described by Captain Symes; and the great recumbent image of Gaudama Buddha called the Shin-bin-tha-lyaung.

Mergui. Mergui (17,297), on the Tenasserim coast, was formerly classed with Rangoon and Negrais as one of the three best ports in the east[11]. Crawfurd writes: "The best and securest harbour, without reference, however, to commercial convenience is that of Mergui....This will admit vessels of almost any burthen, and the ingress and egress are perfectly safe at all times[12]." Mergui is the depot of the pearling industry and has some trade in tin, but is otherwise undistinguished. Notwithstanding its natural advantages, its value as a port is small as it leads nowhither and has no hinterland.

Thatôn. Thatôn (15,091), an inland town in the Tenasserim division, was formerly a Talaing capital and also a seaport. Anawrata destoyed it in the 11th century, and the retrogression of the sea has long left it high and dry. It is on the railway line between Rangoon and Martaban.

Insein. Insein (14,308) is a flourishing and rising railway town, ten miles from Rangoon. Near it are the golf links of Mingaladôn, said to be almost the best course in the East.

Yandoon. Yandoon (12,500)[13], at the junction of the Irrawaddy and the Panlang creek, 60 miles from Rangoon, was formerly a trading town of some importance. It is now one of the few towns with a dwindling population.

Paungdè. Paungdè (14,154) is a railway town in the Prome district, 130 miles from Rangoon.

Thayetmyo. Thayetmyo (10,768), "the city of slaughter," is on the Irrawaddy, a few miles below the old frontier of Upper Burma. Formerly, it was strongly garrisoned, but since the annexation it has sunk into comparative insignificance.

Syriam. Syriam (15,193), not far from Rangoon, was once a provincial capital and, as already noted, the seat of the earliest commercial settlements. It has grown rapidly in recent years, its population in 1891 being under 2000. Now it is the centre of a thriving oil-refining industry.

Upper Burma

Mandalay. In the year 1857, Mindôn Min, following the traditional custom of his House when the throne was filled otherwise than by regular succession, decreed the removal of his court from Amarapura to Mandalay where, in consequence, a populous town arose. The new capital was occupied in 1859. The site chosen was on the left bank of the Irrawaddy, in latitude 20° 59′ N., at a place convenient as a centre of trade with the Northern Shan country. It is not clear that it had any other advantage.

The present town, city, and cantonment occupy an area of 25 square miles. In 1885, Mandalay was the most populous city in Burma, and so it remained for a few years,

the population in 1891 being returned at 188,815, while that of Rangoon was only 182,080. By 1911, the inhabitants of Mandalay had fallen to 138,299. But in the next ten years there was a revival and the number is now 148,917. Mandalay is still essentially a Burmese town, the Buddhist element largely prevailing. Situated 386 miles from Rangoon it is connected with the capital of the province by rail and by river.

The type of Burmese royal city has remained unaltered for ages. Cæsar Frederick's description of Pegu[14] might be adopted almost word for word for Mandalay, save that there were no crocodiles in the moat and there was no ditch round the palace. The commercial and trading quarters extend along the river bank without a break to Amarapura. This low-lying area is protected from inundation by a double embankment built partly for that purpose and partly as a safeguard against hostile attack from the river. In 1886, at the height of the rains, the embankment gave way and the water poured through, flooding the lower part of the town. Boats and launches plied as far as the Zegyo, the great bazaar. In 1885, most of the houses were flimsy structures of wood and bamboo. The greater number of these were destroyed by frequent fires which raged at the end of the hot weather of the following year. Now there are many masonry buildings. Although not a commercial centre of importance, all industries characteristic of the country are practised at Mandalay. A specially flourishing trade is the making of sacred images in marble and steatite. In the middle of the town is the Zegyo, one of the finest covered bazaars in the East, where silks and jewels and miscellaneous goods are displayed in lavish abundance.

Some three miles from the river, stands the Myo or city, encompassed by a moat, 225 feet wide, once covered with lilies, and by battlemented walls, 27 feet high. Each face of the square enclosure is about a mile and a quarter in length. The walls are pierced by twelve gates, each approached by a bridge over the moat, and each surmounted by a pyathat or terraced spire, not used, I think, as sentry boxes. Between these are studded other pyathats making forty-eight in all. One of these surmounts Government House which, being designed in Burmese style, does not outrage aesthetic sensibility. In the middle of the square still stands the Palace. When Mandalay was occupied in 1885, the area around the Palace was crowded with houses of ministers, officers of State, and other Government servants (ahmudan). Each of the more important mansions, mostly built of timber, stood in the midst of its own win, compound, or garden. After the occupation the walled city became a place of arms, the main part of the cantonment which was named Fort Dufferin to commemorate the Governor-General by whom Upper Burma was added to the Empire. In process of time, the whole of the land within

the walls was acquired by Government and all the inhabitants were compensated and expropriated. The space thus cleared was filled with barracks, parade grounds, recreation fields, houses of military and civil officers; and so it remains to this day.

The palace of King Mindôn and King Thebaw was built so recently as 1845 by Shwebo Min and was transported bodily from Amarapura to Mandalay. It was surrounded by a teak wood stockade and two inner encircling walls. On a raised masonry and boarded platform was piled an irregular maze of buildings, mostly in Burmese style, but mingled with some of modern design. East and west, with gilded roofs upheld by lofty pillars of teak, were spacious audience halls, each with its golden throne; for the most exalted ceremonies, in the east, the Lion Throne; in the west, where the ladies of the court paid obeisance, the Lily Throne. Seven other thrones were used on various occasions. Towering above the eastern hall was the famous tapering nine-storeyed spire. Between the two halls were the royal apartments, quarters for princes and princesses, courtiers, maids of honour and pages, offices for ministers, the State Theatre, the Treasury. At the south-eastern corner stood a wooden tower of recent date. Near the eastern gate, beyond the outer wall, was the turret on which was placed the bohozin, the great drum sounded to mark the hours and to give assurance that the king was in his palace. Between the inner wall and the main building stood a small gilded monastery and opposite it the Hlutdaw or Council Chamber where also was the Record Office. Not far away was the shed of the white elephant[15]. The ornamentation of the buildings on the platform was tawdry and barbaric; even the wood-carving was not of special distinction. As a whole, the palace is more curious and interesting than beautiful. But the central pyathat is a model of grace and the pillared halls have a majestic dignity.

Within the enclosure, like Kubla Khan's pleasure-dome, the palace was surrounded by lovely gardens, bright with sinuous rills, where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree and gorgeous tropical flowers, with here a graceful bridge, there a gay pavilion. Here was the summer house where King Thebaw surrendered to General Prendergast. Afterwards this little house acquired even a better title to respect as the temporary abode of Lord Roberts. It has now disappeared.

The palace has been carefully preserved. At first, after the occupation, it was filled with offices and quarters; the western hall became a club house, the eastern hall a church.

Club and church have long since been evicted as well as all residents; and now the lizard and the swarthy darwan[16] keep the empty halls where King Thebaw rioted and revelled. The stockade has been replaced by neat post and rails. The Hlutdaw has crumbled away. But most of the buildings on the platform still stand as in the time of the Burmese monarchy.

To the north is Mandalay Hill, 950 feet high, whereon stood an upright image of the Buddha, with arm outstretched, the Palladium of the city. The image, destroyed by fire some years ago, has been replaced. On a spur of the hill has been built a temple to receive relics of Gaudama recovered from a pagoda near Peshawar erected by the Emperor Kanishka. East are the Shan Hills and in the middle distance the isolated little hill of Yankintaung, the hill of peace.

Mandalay is studded with pagodas and monasteries, for the most part modern. South of the town is the Arakan Pagoda or rather Temple (Yakaing Paya), enshrining the great Mahamuni image, cast in the second century of our era, and brought from Arakan in 1784. Here also are six antique and much dilapidated bronze images, two men, three lions, and a three-headed elephant. The corridors leading to the shrine are adorned with frescoes. In a small lake or pond are tame tortoises fed by the pious. Here, for the present, are kept the relics from Peshawar.

Some other pagodas may be mentioned. Kyauktawgyi covers an image of the Buddha made in marble under the orders of Mindôn Min. At Sandemani are the graves of the Einshemin (heir apparent), and the Sagu and Malun princes, killed in the abortive rising of the Myingun prince in 1866. Kuthodaw, not far from the foot of Mandalay Hill, is one of the most remarkable. In the midst is a graceful pagoda; around it are 729 stone slabs on which are inscribed the whole of the Tripataka or Buddhist scriptures. Setkyathila covers a bronze image of the Buddha cast under the orders of King Bagyidaw. One of the finest specimens of Burmese art, the image is somewhat fancifully regarded as of sinister omen. Its casting at Ava in 1823 was followed by the First War in 1824; its removal to Amarapura in 1849 by the Second War in 1852; its final transfer to Mandalay in 1884 by the Third War in the following year. Eindawya, built by Pagan Min in 1847, is of conspicuous merit; Menaung Yawana, built in 1881, may commemorate King Thebaw. The Atumashi, or Incomparable, a large and beautiful temple covered with white stucco, enshrining a great image of the Buddha, was destroyed by fire in 1890. Paya-ni, the Red Pagoda, dates from 1092. Attached to it are two

images, Naungdaw and Nyidaw, of the time of Anawrata. In its present form, Shwekyimyin dates only from 1852 but was superimposed on an old pagoda of 1104. It covers a great brazen image of Gaudama as well as other sacred images, notably one, Shwelinbin, representing Gaudama in royal robes, said to have been moved from capital to capital since the time of King Narapati-sithu of Pagan (11th century). A small nameless pagoda was built by Shinbome, a famous beauty, who, with the necessary variation almost equalling the exploits of Henry VIII, married five kings in succession.

Many monasteries, built by kings, queens and courtiers, adorn the town. The best known is the Queen's Monastery, finished by Supayalat just before the Third War. At the time of the annexation its gold was fresh and gleaming. Shwenandaw, built by King Thebaw in 1880, and Salin, by Salin Supaya, a favourite child of Mindôn Min, daughter of the Limban queen, as well as the Queen's Monastery, are all remarkable for beautiful wood-carving, that on Salin being probably the finest in Burma. Sangyaung was built in 1859 by Mindôn Min. Taiktaw is the official residence of the Thathanabaing[17].

Pakôkku. Pakôkku (19,507), on the right bank of the Irrawaddy, near its junction with the Chindwin, is described by Crawfurd as

"a place of considerable extent and population. The inhabitants" he writes "poured out on the banks to see the steam-vessel, and formed such a concourse as we had nowhere seen unless at Prome. [Pakôkku] is a place of great trade, and a kind of emporium for the commerce between Ava and the lower country; many large boats which cannot proceed to the former in the dry season, taking in their cargoes at this place. We counted one hundred and fifty trading vessels, of which twenty one were of the largest size of Burman merchant-boats[18]."

But in 1889 the population was estimated at no more than 8000. Since then Pakôkku has thriven and is now again a busy industrial and trading centre and an important timber depot.

Myingyan. Myingyan (18,931), on the left bank of the Irrawaddy, about 80 miles below Mandalay, connected by a branch line from Thazi with the Rangoon-Mandalay railway, is an industrial and trading town of some note, the seat of busy cotton mills. It suffers from being cut off from the river in the dry season by sandbanks.

Pyinmana. Pyinmana (14,886), on the Mandalay railway, 226 miles from Rangoon, derives its importance from its proximity to valuable teak forests. It was one of the first inland towns occupied at the time of the invasion of Upper Burma in 1885.

Maymyo. Maymyo (16,558), already mentioned as the summer capital, is situated on the border of the Shan sub-State of Hsum-sai[19] (Thonze), east of Mandalay, on a wide plateau some 3500 feet above the sea. Built on the site of the village of Pyin-u-lwin and named after its first Commandant, Colonel May of the Indian army, Maymyo owes its prosperity entirely to British occupation. When first visited towards the end of 1886, Pyin-u-lwin consisted of about fifty houses, a monastery, a market place, and a gambling ring. Now the railway from Mandalay to Lashio passes through it and there is also connection with Mandalay by a good motor road. Besides being the seat of Government in the hot season, it is the military headquarters of Burma, and the resort of many visitors from the plains. There is ample room for a race-course, golf links, polo, cricket and football grounds, a club, barracks, private houses with delicious gardens, and public offices. Carriage drives and good roads for motoring have been laid out. To Sir Hugh Barnes, the second Lieutenant-Governor, is due the provision of some 60 miles of rough rides through the forest on the outskirts. Maymyo is singularly unlike typical eastern places; it has been described as more like a corner of Surrey. The only conspicuous native feature is the bazaar or market, held after Shan fashion every five days, where strange people from the hills in picturesque attire mingle with Europeans and Shans and Burmans.

Mogôk. Mogôk (11,069)[20] was from 1887 to 1920 the headquarters of the Ruby Mines district, recently absorbed into Katha. Picturesquely situated amid lofty hills, at an elevation of about 4000 feet, connected with the Irrawaddy at Thabeik-kyin by a motor road 60 miles in length, it is important solely as the centre of the ruby mining industry. It has always been a wealthy town where, in the bazaar

in 1887, copper coins were unknown. A few miles away, at a greater height, is Bernard-myo, commemorating Sir Charles Bernard, the distinguished officer who was the first Chief Commissioner in Upper Burma.

Sagaing. Sagaing (11,737), one of many ancient capitals, is a typical Burmese town, embowered in tamarind groves, on the right bank of the Irrawaddy a few miles below Mandalay. It is the southern terminus of the railway to Myit-kyi-na and is also connected by rail with Mônywa and Alôn on the Chindwin. From Mandalay, a steam ferry plies several times a day in connection with the railway. Except as the headquarters of a Division and District, Sagaing has no special importance but it has many associations and notable neighbours. Nearly opposite on the left bank of the river stood the ancient and famous city of Ava, now in ruin and decay. A little to the north is the great bell of Mingun, the largest hung bell in the world. Cast in 1790, it weighs 80 tons, with a height of 12 feet and a diameter at the mouth of 16 feet. It was re-hung a few years ago. Close by, at Mingun, is a vast uncompleted pagoda planned by Bodawpaya to be of unapproached dimensions, but abandoned after it had been split by an earthquake in 1839. With a base of 450 feet square and height of 162 feet, it enjoys the unromantic distinction of being the greatest mass of solid brick work extant. Hard by is Sinbyushin, a beautiful terraced pagoda, dating from the 14th century. To the north the hills along the river are crowned with white pagodas in picturesque disorder; hollowed out of the hills are cave dwellings of hermits.

Shwebo. Shwebo (10,605), an inland town on the Myitkyina railway, is noted as the birth-place of Alaungpaya and the capital of his kingdom. Traces of the royal city still remain. In Burmese times Shwebo was often the seed- plot of rebellion.

Bhamo. Bhamo (7741), an ancient town on the left bank of the Irrawaddy, 687 miles from the sea, is an emporium of the caravan trade with China. It is one of the places to which European traders first penetrated. Among its inhabitants are a fair sprinkling of Chinese from Yünnan and some from Canton; its most conspicuous building is an elaborately ornamented Chinese temple Bhamo is important as a frontier garrison town, having been occupied immediately after the taking of Mandalay.

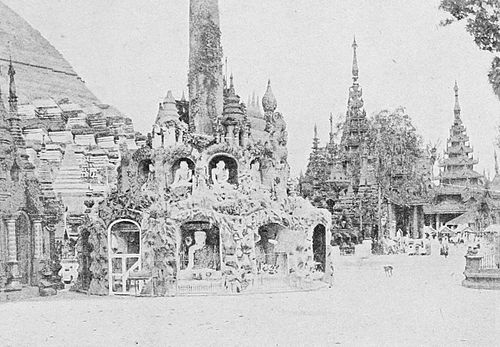

Amarapura. Amarapura (7866)[21], a decaying town, practically a suburb of Mandalay, is chiefly notable as a former capital. It still has some

Fig. 78. Shrine at Amarapura. economic importance, with an exceedingly useful silk-weaving institute and with many carvers of images. Here used to be the kheddah, the enclosure into which wild elephants were enticed in the king's time and in our early years. Here are many famous pagodas; the Shwegyetyet group, 600 years old; Patodawgyi, a very large and beautiful pagoda decorated with glazed tiles, the work of King Bagyidaw in 1818; and Kyauktawgyi built by Pagan Min in 1847 on the model of the Ananda at Pagan, its porches adorned with frescoes.

Pagan. Pagan (6254)[22], on the left bank of the Irrawaddy, below Myingyan, is one of the most remarkable places in the world. The most renowned of ancient Burmese capitals, it is still a wonder-house of archaeological relics. So long ago as the 2nd century of our era, a city was built on this site. But Pagan, of which the ruins are extant, was founded by King Pyinbya in 847 A.D. In 1057 Anawrata, most renowned of Burmese kings, destroyed the kingdom of Thatôn and brought to his capital King Manuha and many Talaing captives. From this date begins the epoch of pagoda-building at Pagan, lasting till the sack of the city by the Mongols and Chinese of Kublai Khan in 1284, and embracing the reigns of Anawrata, Kyansittha, Alaung-sithu, Narapati-sithu, and Talokpye Min. For miles along the river bank are still standing some 5000 pagodas and Buddhist temples, Pagan itself extending for five miles with a breadth of two miles; but the area occupied by sacred buildings at Pagan and in the vicinity is about 100 square miles[23]. Shortly before the Mongol invasion, Marco Polo describes Pagan which he calls Amien, the capital city of the province of that name, as "a very great and noble city[24]."

"And in this city," he writes, "there is a thing so rich and rare that I must tell you about it. You see there was in former days a rich and puissant King in this city and when he was about to die he commanded that by his tomb they should erect two towers (one at each end), one of gold and the other of silver, in such fashion as I shall tell you. The towers are built of fine stone; and the one of them has been covered with gold, a good finger in thickness, so that the tower looks as if it were all of solid gold; and the other is covered with silver in like manner so that it seems to be all of solid silver. Each tower is of a good ten paces in height and of breadth in proportion. The Upper Part of these towers is round, and girt all along with bells, the top of the gold tower with gilded bells and the silver tower with silvered bells, insomuch that whenever the wind blows among these bells they tinkle. The King caused these towers to be erected to commemorate his magnificence and for the good of his soul, and really they do form one of the finest sights in the world; so exquisitely finished are they, so splendid and costly."

Unhappily no remains of these exquisite buildings can be traced, but many worthy compeers survive. In the classical description of the antiquities of Pagan, Sir Henry Yule thus summarizes the several styles of architecture:

The bell-shaped pyramid of dead brickwork in all its varieties; the same raised over a square or octagonal cell, containing an image of the Buddha; the bluff, knob-like dome of the Ceylon Dagobahs, with the square cap which seems to have characterized the most ancient Buddhist chaityas, as represented in the sculptures at Sanchi, and in the ancient model pagodas found near Buddhist remains in India; the fantastic boo-payah, or pumpkin pagoda, which seemed rather like a fragment of what we might conceive the architecture of the moon than anything terrestrial, and many variations of these types. But the predominant and characteristic form is that of the cruciform vaulted temple[25].

Ananda. The most famous temple is the Ananda, of Jain architecture, with vaulted chambers and corridors, built in the year 1091 and still standing almost untouched by time. It contains stone sculptures representing scenes of Gaudama's life and terra cotta tiles picturing events of his former existences, as well as images of the founder King Kyansittha and of the last four Buddhas of the present cycle.

Tha-byin-nyu, another magnificent temple, built by Alaung-sithu in 1244 after models of temples in Northern India, is thus described:

...The form of the temple is an equilateral quadrangle, having on each side four large wings, also of a quadrilateral form. In these last are the entrances, and they contain the principal images of Gautama. Each side of the temple measures about two hundred and thirty feet. The whole consists of four stages, or stories, diminishing in size as they ascend. The ground story only has wings. The centre of the building consists of a solid mass of masonry: over this, and rising from the last story of the building, is a steeple, in form not unlike a mitre, ending in a thin spire, which is crowned with an iron umbrella, as in the modern temples. Round each stage of the building is an arched corridor, and on one side a flight of steps leads all the way to the last story.... Perhaps the most remarkable feature of this temple, as well as of almost all the other buildings of Pagan, is the prevalence of the arch. The gate ways, the doors, the galleries, and the roofs of all the smaller temples, are invariably formed by a well-turned Gothic arch[26].

Other notable temples of Indian types and giving evidence of Indian influence are Maha Bodi, a copy of the shrine at

Buddha Gaya in Bengal and Gawdapalin, built by Nara-pati-sithu in the 12th century. Of a small unnamed temple, Crawfurd writes: "within the chamber were two good images in sandstone, and sculptured in high relief. One of these was Vishnu or Krishna, sitting on his Garuda; and the other Siwa, the destroying power, with his trisula, or trident, in one hand and a mallet in the other[27]." The first temple built by Anawrata enshrines hairs of the Buddha; the corners of the lowest terrace are guarded by images of Brahma, Vishnu, and Siwa.

Specially deserving of mention are Shwegugyi, built by Alaungsithu in the 12th century; Tilomile, a two-storeyed building, dating from 1218; and Shwezigôn, one of the oldest buildings in Pagan.

A few hundred yards South of [Shwezigôn] lies ensconced amid green verdure and ruins, Kyansittha's Ônhmin or the Cave Temple of King Kyansittha (1084—1112 A.D.). It is a brick building of unpretentious dimensions, and is almost hidden from view because its site has been scooped out of a sand-dune. As the Ananda temple is the store-house of the finest statuary in stone in Burma, so this Cave Temple contains the best collection of exquisite frescoes illustrating Burmese civilization, probably before the 11th century A.D. Such Cave Temples are numerous in the neighbourhood[28].

Dhammayazaka temple, built by King Narapatisithu, 1196, contains images of the five Buddhas of the present cycle including Arimetteyya who is still to appear.

Besides temples and pagodas, many in good preservation, ruined monasteries abound in great numbers and of various types[29]. Enough has been cited to indicate the extreme wealth of Pagan in archaeological treasures to the examination of which much labour has been devoted in recent years.

The flourishing and unique lacquer industry has already been described.

- ↑ For an admirable and interesting account of "Old Rangoon," by Prof. W. G. Fraser, see Journal of the Burma Research Society, x. ii.

- ↑ Hakluyt, ii. 393.

- ↑ Symes, 217.

- ↑ Re = 1s. 4d.

- ↑ These details are abstracted from accounts by Sir George Buchanan, K.C.I.E., under whose direction the works were executed.

- ↑ Except where otherwise stated, the figures in brackets give the population according to the census of 1921.

- ↑ See p. 12.

- ↑ The celebrated naturalist and explorer.

- ↑ Godown, a store room, is a word still commonly used.

- ↑ Hakluyt, ii. 362.

- ↑ Symes.

- ↑ Crawfurd, 478.

- ↑ In 1911.

- ↑ See p. 182.

- ↑ This loyal beast declined to survive the downfall of his sovereign.

- ↑ Watchman.

- ↑ See p. 128.

- ↑ Crawfurd, 74.

- ↑ Absorbed in Hsipaw.

- ↑ In 1911.

- ↑ In 1911.

- ↑ In 1901.

- ↑ Taw Sein Ko, C.I.E. Archaeological Notes on Pagan.

- ↑ Marco Polo, 11. 109.

- ↑ The Court of Ava, 35.

- ↑ Crawfurd, 63—4.

- ↑ Crawfurd, 69.

- ↑ Taw Sein Ko, Burmese Sketches, 11. 303.

- ↑ Cf. Captain W. B. Sinclair's "The Monasteries of Pagan." Journal of the Burma Research Society, x. i.