Rude Stone Monuments in All Countries/Chapter 10

CHAPTER X.

ALGERIA.

It would be difficult to find a more curious illustration of the fable of "Eyes and no Eyes" than in the history of the discovery of dolmens in northern Africa. Though hundreds of travellers had passed through the country since the time of Bruce and Shaw, and though the French had possessed Algiers since 1830, an author writing on the subject ten years ago would have been fully justified in making the assertion that there were no dolmens there. Yet now we know that they exist literally in thousands. Perhaps it would not be an exaggeration to say that ten thousand are known, and their existence recorded.

The first to announce the feet to the literary world in Europe was the late Mr. Rhind. He read a paper on what he called "Ortholithic remains in North Africa," to the Society of Antiquaries in 1859, which was afterwards published in volume xxxviii. of the 'Archæologia.' It attracted, however, very little attention, perhaps in consequence of its name, but more from its not being illustrated. It was not really till 1863, when the late Henry Christy visited Algeria, that anything really became known. At Constantine he formed the acquaintance of a M. Féraud, interpreter to the army of Algeria, who took him to a place called Bou Moursug, about twenty-five miles south of Constantine, where, during a short stay of three days, they saw and noted down upwards of one thousand dolmens.[1] M. Féraud afterwards published an account of these in the 'Mémoires de la Société archéologique de Constantine' for 1863, and the subject having attracted some attention in Europe, a second memoir appeared in the following year, which contained a good deal of additional information collected from different district officers. Since then various memoirs have been published in Algeria and France. One by the now celebrated General Faidherbe "speaks of three thousand tombs in the single necropolis at Roknia, and of another equally extensive within a few leagues of Constantine."[2] An excellent résumé of the whole subject will be found in the Norwich volume of the International Prehistoric Congress, by Mr. Flower. From all these we gather a fair general idea of the subject, but, unfortunately, none of the memoirs are written by persons combining extensive local experience with real archæological knowledge, except, perhaps, Mr. Flower. No plan of any one group has yet been given to the world, nor are any of the monuments illustrated with such details and measurements as would enable one to speak with certainty regarding them. This is especially the case with those represented in the 'Exploration scientifique de l'Algérie,' published by the French Government. There are in this work numerous representations of dolmens carefully and beautifully drawn, but very seldom with scales attached to them; and as no text has yet been published, they are of comparatively little value for the purposes of research. Had Mr. Christy lived a little longer, these deficiencies would doubtless have been supplied; but, unfortunately, his mantle has not fallen on any worthy successor, and we must wait till some one appears who combines leisure and means with the knowledge and enthusiasm which characterized that noble-minded man.

It need hardly be added that no detailed map exists showing the distribution of the dolmens in Algeria,[3] and as many of the names by which they are known to French archæologists are those of villages not marked on any maps obtainable in this country, it is very difficult to trace their precise position, and almost always impossible to draw with certainty any inferences from their distribution. In so far as we at present know, the principal dolmen region is situated along and on either side of a line drawn from Bona on the coast to Batna, sixty miles south of Constantine. But around Setif, and in localities nearly due south from Boujie, they are said to be in enormous numbers. The Commandant Payen reports the number of menhirs there as not less than ten thousand, averaging from 4 to 5 feet in height. One colossal monolith he describes as 26 feet in diameter at its base and 52 feet high.[4] This, however, is surpassed by a dolmen situated near Tiaret, described by the Commandant Bernard. According to his account the cap-stone is 65 feet long by 26 feet broad, and 9 feet 6 inches thick; and this enormous mass is placed on other rocks which rise between 30 and 40 feet above the surface.[5] If this is true, it is the most enormous dolmen known, and it is strange that it should have escaped observation so long. Even the most apathetic traveller might have been astonished at such a wonder. Whether less gigantic specimens of the class exist in that neighbourhood, we are not told, but they do in detached patches everywhere eastward throughout the province. Those described by Mr. Rhind are only twelve miles from Algiers, and others are said to exist in great numbers in the regency of Tripoli.[6] So far as is at present known, they are not found in Morocco, but are found everywhere between Mount Atlas and the Syrtes, and apparently not near the sites of any great cities, or known centres of population, but in valleys and remote corners, as if belonging to a nomadic or agricultural population.

When we speak of the ten thousand or, it may be, twenty thousand stone sepulchral monuments that are now known to exist in northern Africa, it must not be understood that they are all dolmens or circles of the class of which we have hitherto been speaking. Two other classes certainly exist, in some places, apparently, in considerable numbers, though it is difficult to make out in what proportion, and how far their forms are local. One of these classes, called Bazina by the Arabs, is thus described by Mr. Flower:—"Their general character is that of three concentric enclosures of stones of greater or less dimensions, so arranged as to form a series of steps. Sometimes, indeed, there are only two outer circles, and occasionally only one. The diameter of the larger axis of that here represented is about 30 feet. In the centre are usually found three long and slender upright stones, forming three sides of a long rectangle, and the interior is paved with pebbles and broken stones.

"The Chouchas are found in the neighbourhood of the Bazinas, and are closely allied to them. They consist of courses of stones regularly built up like a wall, and not in steps like the Bazinas. Their diameter varies from 7 to as much as 40 feet; but the height of the highest above the soil does not exceed 5 to 10 feet. They are usually capped and covered by a large flag-stone, about 4 inches thick, under which is a regular trough or pit formed of stones from a foot and a half to 3 feet in thickness. The interior of these little towers is paved like the Bazinas; and indeed M. Payen considers that they are the equivalents in the mountains of the Bazinas in the plains."[7]

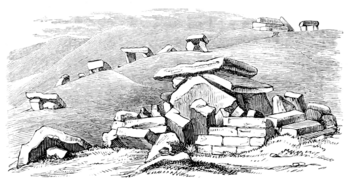

In many instances the chouchas and bazinas are found combined in one monument, and sometimes a regular dolmen is mounted on steps similar to those of a bazina, as shown in the annexed woodcut, representing one existing halfway between Constantine and Bona. But, in fact, there is no conceivable combination which does not seem to be found in these African cemeteries; and did we know them all, they might throw considerable light on some questions that are now very perplexing.

The chouchas are found sometimes isolated, and occasionally 10 to 12 feet apart from one another in groups. In certain localities the summits and ridges of the hills are covered with them, while on the edges of steep cliffs they form fringes overhanging the ravines.

In both these classes of monuments the bodies are almost always found in a doubled-up posture, the knees being brought up to the chin, and the arms crossed over the breast,[8] like those in the Axevalla tomb described above (page 312).

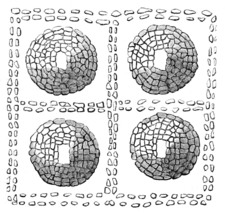

The most remarkable peculiarity of the tumuli and circles in Algeria is the mode in which they are connected together by double lines of stones—as Mr. Flowers expresses it, like beads on a string—in the manner shown in woodcut No. 167. What the object of this was has not been explained, nor will it be easy to guess, till we have more, and more detailed, drawings than we now possess. Mr. Féraud's plate xxviii.[9] shows such a line zigzagging

across the plain between two heights, like a line of field fortifications, and with dolmens and tumuli sometimes behind or in front of the lines, and at others strung upon it. At first sight it looks like the representation of a battle-field, but, again, what are we to make of such a group as that represented in woodcut 168 on the previous page? It is the most extensive plan of any one of these groups which has yet been published, but it must be received with caution.[10] There is no scale attached to it. The triple circles with dolmens I take to be tumuli, like those of the Aveyron (woodcuts Nos. 8 and 122), but the whole must be regarded as a diagram, not as a plan, and as such very unsafe to reason upon. Still, as it certainly is not invented, it shows the curious manner in which these monuments are joined together, as well as the various forms which they take.

One of these (?) is represented in plan and elevation in the annexed woodcut 169.[11] It is, as will be observed, almost identical— making allowance for bad drawing—with those of Aveyron just referred to, or with the Scandinavian examples as exemplified in the diagram (woodcut No. 109). As this class with the external dolmen on the summit seems to be very extensive in Algeria, indeed almost typical, an examination of their interior would at once solve the mystery of their arrangements, and tell us whether there was a second cist on the ground level, or where the body was deposited. Where the dolmen stands free, but on the flat ground, as is the case with that shown in this cut (No. 170), with two rows of stones surrounding it, the body was deposited in a cist formed between the two uprights that support the cap-stone, which are carried down some 5 or 6 feet into the ground for that purpose. My impression is that the same arrangement is met with in those which are raised, and that either the supports of the cap-stone are carried down to the ground for that purpose or that an independent cist is formed directly under the visible one.

The dolmen in this last instance is of the usual Kit's Cotty House style, consisting of three upright stones supporting the cap-stone. Sometimes the outer row of stones is replaced by a circular pavement of flat stones,[12] forming what may be supposed to be a procession path round the monument; but in fact hardly any two are exactly alike, and when we come to deal with thousands, it requires very complete knowledge of the whole before any classification can be attempted. Suffice it to say here that there is hardly any variety met with elsewhere of which a counterpart cannot be found in Algeria.

Of their general appearance as objects in the landscape, the annexed woodcut will convey a tolerable idea. They seem to affect the ridges of the hills, but they also stretch across the plain, and in fact are found everywhere and in every possible position. Except apparently on the sea-coast, nothing like the Viking graves, so far as is known, is found in Algeria; whether this indicates that they were a sea-faring people or not is not quite clear, but it is a distinction worth bearing in mind.

One curious group is perhaps worth quoting as a means of comparison with the graves of Aschenrade (woodcut No. 119). It consists of four tumuli enclosed in four squares joined together like the squares of a chess-board. Single squares enclosing cairns are common enough in Scandinavia, but this conjoined arrangement is rare and remarkable, and its similarity to the Livonian example is so great that it can hardly be accidental. The Aschenrade graves, it will be recollected, contained coins of the Caliphs extending down to A.D. 999, and German coins down to 1040. There would, therefore, be no à priori improbability in these graves in Algeria being as late, if the similarity of two monuments so far apart can be considered as proving identity of age. Without unduly pressing the argument, the points of resemblance which exist everywhere between the Northern Europe and North African monuments appear to prove that the latter may be of any age down to the tenth or eleventh century, but any decision as to their real date must depend on the local circumstances attending each individual example.

The preceding woodcuts are perhaps sufficient to explain the more general and more typical forms of Algerian dolmens, but they are so numerous and so varied that ten times that number of illustrations would hardly suffice to exhibit all their peculiarities. Their study, however, is comparatively uninteresting, till we know more of their contents, and till something definite is accepted as to their age. When, however, we turn to examine that, we find the data from which our conclusions must be drawn both meagre and unsatisfactory. Such as they are, however, they certainly all tend one way. In the first place, the negative evidence is as complete here as elsewhere. The Greeks, the Romans, and the early Christians were all familiar with northern Africa, and there is not one whisper as to any such monuments having been seen by any of them. When we consider our own ignorance of their existence till some ten years ago, it may be said that such evidence does not go for much; but it is worth alluding to, as a hint in the opposite direction would be considered final, and as its absence, at all events, leaves the question open. On the other hand, all the traditions of the country as reported by M. Féraud, and others, and repeated by M. Bertrand and Mr. Flower, ascribe these monuments to the pagan inhabitants who occupied the country at the time of the Mahommedan conquest. Thus (page 127): "At the epoch the Mussulman invasion these countries were inhabited by a pagan population, who elevated these vast ranges of stone to arrest the invading host." Or, again, they even name the prince who opposed the conquerors. Thus (page 117): "Formerly at Machira lived a pagan prince called Abd en Nar—fire worshipper. He married Zana, queen of a city now in ruins bearing that name. When the Arabs conquered Africa, Abd en Nar abjured his crown, became a Mussulman, and from that time called himself Abd en Nour—worshipper of the light."[13]

This, too, must be taken for what it is worth; but in a cemetery near Djidjeli, on the north coast, there is a curious tomb formed of a circle of stones like those of the pagan cists, with a headstone which, if it is not the turban-stone that is usually found in Turkish tombs of modern date, is most singularly like it. That the cemetery belongs to the Mahommedans seems clear, but the circles of stones, though small, indicate a very imperfect conversion—just such as the tradition indicates.

These arguments, however, acquire something like consistency when we come to examine the contents of the tombs themselves. One of them (No. 4) is described by Mr. Féraud as surrounded by a circular enceinte, 12 metres, nearly 40 feet, in diameter. The chamber of the dolmen measured 7 feet by 3 feet 6 inches. At the feet of the skeleton were the bones and teeth of a horse, and an iron bridle-bit. In the same grave were found a ring of iron, another ring with various other objects in copper (bronze?), some fragments of pottery of a superior quality, and fragments of worked flint implements, and lastly a medal of the Empress Faustina.[14] All the three ages were consequently represented in the one tomb, and yet it certainly belongs to the second century. None of the others give such distinct evidence of their age, but M. Bertrand, who is a strong advocate for the prehistoric age of French dolmens, sums up his impressions of M. Féraud's discoveries in the following words: "Ceux de la province de Constantine ne pouvaient, à en juger par les objets qui y ont été trouvés, être de beaucoup antérieur a l'ère chrétienne; quelques-uns même seraient postérieurs."[15]

In addition to what he found inside the tombs, M. Féraud discovered a Latin inscription in the cap-stone of a dolmen near Sidi Kacem. The letters are too much worn to enable the sense of the inscription to be made out, but quite sufficient remains to prove that it is in Latin, and, from the form of the letters, of a late type.[16]

Monsieur Leternoux found hewn stones and even columnar shafts of Roman workmanship among the materials out of which the bazinas at the foot of the Aures chain had been constructed, and he gives a drawing of a cippus of late Roman workmanship, bearing an inscription in Berber character, which he identifies with those on two upright stones of rude form, one of which forms parts of a circle near Bona.[17]

In addition to these there are numerous instances among the plates which form the volume of the 'Exploration scientifique de l'Algérie' where the rude-stone monuments are so mixed up with those of late Roman and early Christian character that it seems impossible to doubt that they are contemporary. As no text, however, has yet been published to accompany these plates, it is most unsafe to rely on any individual example, which from some fault of the draughtsman or engraver may be misleading. The general impression, however, which these plates convey is decidedly in favour of a post-Roman date, and of their being comparatively modern. It requires, however, some one on the spot, whose attention is specially directed to the subject, to determine whether the rude-stone monuments are earlier than those which are hewn, or whether the contrary is not sometimes, perhaps always, the case. If M. Bertrand is right, and the Faustina tomb is of any value as an indication of age, certainly sometimes at least, the rude monuments are the more modern. Carthage fell B.C. 146, and the Jugurthan war ended B.C. 106, and it is impossible to conceive that a people like the Romans, would possess as they did the sovereignty of northern Africa, after that date, and not leave their mark on it, in the shape of buildings of various sorts. If we adopt the usual progressive theory, all must be anterior to B.C. 100; for on that hypothesis it would be considered most improbable that after long contact with Carthaginian civilization and under the direct influence of that of Rome anyone could prefer rude uncommunicative masses to structures composed of polished and engraved stones. It certainly was so, however, to a very great extent, and my impression is, for the reasons above given, that the bulk of these North African dolmens are subsequent to the Christian era, and that they extend well into the period of the Mahommedan domination, for it could not, for a long time at least, have been so complete as entirely to obliterate the feelings and usages so long indulged in by the aboriginal inhabitants of the country. Nothing, indeed, would surprise me less than if it were eventually shown that some of these rude-stone monuments extended down to the times of the Crusades. As, however, we are not yet in a position to prove this, it is only put forward here as a suggestion, in order that those who may hereafter have the task of opening these tombs may not reject any evidence of their being so late, as they probably would do if imbued with prehistoric prejudices.

It is to be feared that the question who the people were that set these African dolmens must wait for an answer till we know more of the ethnography of northern Africa in ancient times than we do at present. The only people who, so far as we now see, seem to be able to claim them, are the Nasamones. From Herodotus we learn that this people buried their dead sitting, with their knees doubled up to their chins, and were so particular about this that, when a man was dying, they propped him up that he might die in that attitude (iv. 190). We also learn from him that they had such reverence for the tombs of their ancestors that it was their practice in their solemn form of oath to lay their hands on these tombs, and so invoke their sanction; and in their mode of divination they used to sleep in or on these sepulchres (iv. 172). All this would agree perfectly with what we find, but Herodotus unfortunately never visited the country nor saw these tombs, and consequently does not describe them, and we do not know whether they were mere mounds of earth, or cairns of stone, or dolmens such as are found in Africa. It is also unfortunate for their claim that, in his day, the Nasamones lived near the Syrtes and to the eastward of them (ii. 32), and it seems hardly possible that they could have increased and multiplied to such an extent in the four following centuries as to occupy northern Africa as far as Mount Atlas, without either the Greeks or the Romans having known it. They are mentioned again by Curtius (iv. 7), by Lucan (ix. v. 439), and by Silius Italicus (ii. v. 116 and xi. v. 180), but always as a plundering Libyan tribe, never as a great people occupying the northern country. Their claim, therefore, to be considered the authors of the thousands of dolmens which are even now found in the province of Algeria, seems for the present wholly inadmissible.

Still less can we admit M. Bertrand's theory alluded to above, that the dolmen-builders migrated from the Baltic to Britain, and thence through France and Spain to Africa. Such a migration, requiring long land journeys and sea voyages, if it took place at all, is much more likely to have been accomplished when commercial intercourse was established, and the North Sea and the Mediterranean were covered with sailing vessels of all sorts; but then it is unlikely that a rude people, as the dolmen-builders are assumed to be, could have availed themselves of these trade routes.

Still no one can look at such monuments as this of Aveyron (woodcuts Nos. 8 and 122) and compare them with those of Algeria, of which woodcut No. 169 is a type, without feeling that there was a connection, and an intimate one, at the dolmen period, between the people on the northern with those on the southern shores of the Mediterranean, which can only be accounted for in one of three ways.

Either it was that history was only repeating itself when Marshal Bougeaud landed in Algeria in 1830, and proceeded to conquer and colonise Algeria for the French. Or we must assume, as has often been done, that some people wandering from the east to colonise western Europe left these traces of their passage in Africa on their way westward. The third hypothesis is that already insisted upon at the end of the Scandinavian chapter, which regards these rude-stone monuments as merely the result of a fashion which sprung up at a particular period, and was adopted by all those people who, like the Nasamones, reverenced their dead and practised ancestral worship rather than that of an external divinity.

Of all these three hypotheses, the second seems the least tenable, though it is the one most generally adopted. The Pyramids were built, on the most moderate computation, at least 3000 B.C.[18] Egypt was then a highly civilized and populous country, and the art of cutting and polishing stones of the hardest nature had reached a degree of perfection in that country in those days which has never since been surpassed, and must have been practised for thousands of years before that time in order to reach the stage of perfection in which we there find it. Is it possible to conceive any savage Eastern race rushing across the Nile on its way westward, and carrying their rude arts with them, and continuing to practise them for four or five thousand years afterwards without change? Either it seems more probable to assume that the Egyptians would have turned them back, or if they had sojourned in their land like the Israelites, and then departed because they found the bondage intolerable, it is almost certain that they would have carried with them some of the arts and civilization of the people among whom they had dwelt. If such a migration did take place, it must have been in prehistoric times so remote that its occurrence can have but little bearing on the argument as to who built these Algerian monuments. But did they come by sea? Did the dolmen-building races embark from the ports of Palestine or those of Asia Minor? Were they in fact the far-famed Phoenicians, to whom antiquaries have been so fond of ascribing these structures. The first answer to this is that there are no dolmens in Phœnicia, and that they have not yet been found near Carthage, nor Utica, nor in Sicily, nor indeed anywhere where the Phœnicians had colonies. They are not even found at Marseilles, where they settled, though on the western bank of the Rhone, where they had no establishments, they are found in numbers. They may have traded with Cornwall, and discovered lands even farther north, but to assume that so small a people could have erected all the megalithic remains found in Scandinavia and the continent of France, and other countries where they never settled, perhaps never visited, is to ascribe great effects to causes so insignificant as to be wholly incommensurable. So wholly inadequate does the Phœnician power seem to have been to produce such effects, that the proposition would probably never have been brought forward had the extent of the dolmen region been known at the time it was suggested. Even putting the element of time aside, it is now clearly untenable, and if there is any truth in the date above assigned to this class of monuments, it is mere idleness to argue it.

The idea of a migration from France to Algeria is by no means so illogical. The French dolmens, so far as is now known, seem certainly older than the African—a fact which, if capable of proof, is fatal to the last suggestion—and if we assume that this class of monument was invented in western Europe, it only requires that the element of time should be suitable to establish this hypothesis. When the Celts of central Gaul, six centuries before the Christian era, began to extend their limits and to press upon those of the Aquitanians, did the latter flee from their oppressors to seek refuge in Africa, as at a latter period the dolmen-builders of Spain sought repose in the green island of the west? There certainly appears to be no great improbability that they may have done so to such an extent as to cause the adoption of this form of architecture after it had become prevalent elsewhere; and as the encroaching Celts, down to the prosecution of the middle ages, may have driven continual streams of colonists in the same direction, this would account for all the phenomena we find, provided we may ascribe that modern date to the Algerian examples which to me appears undoubted.

It is hardly probable, however, that the Aquitanians would have sought refuge in Africa unless some kindred tribe existed there to afford them shelter and a welcome. If such a race did exist, that would go far to get rid of most of the difficulties of the problem. We are, however, far too ignorant of North African ethnography to be able to say whether any such people were there, or if so, who their representatives may now be, and till our ignorance is dispelled, it is idle to speculate on mere probabilities.

We know something of the migrations of the peoples settled around the shores of the Mediterranean for at least ten centuries before the birth of Christ, but neither in Greek or Roman or Cathaginian history, nor in any of the traditions of their literature, do we find a hint of any migration of a rude people, either across Egypt or by sea from Asia, and, what is perhaps more to the point, we have no trace of it in any of the intermediate islands. The Nurhags of Sardinia, the Talayots of the Balearic Islands, are monuments of quite a different class from anything found in France or Algeria. So too are the tombs of Malta, and, as just mentioned, there are no such remains in Sicily.

We seem thus forced back on the third hypothesis, which contemplates the rise of a dolmen style of architecture at some not very remote period of the world's history, and its general diffusion among all those kindred races of mankind with whom respect for the spirits of deceased ancestors was a leading characteristic.

Tripoli.

Dr. Barth seems to be the only traveller who has in recent times explored the regions about Tripoli to a sufficient extent and with the requisite knowledge to enable him to observe whether or not there were any rude-stone monuments in that district. About halfway between Moursuk and Ghât, he observed "a circle laid out very regularly with large slabs, like the opening of a well; and, on the plain above the cliffs, another circle regularly laid out, "and," he adds, "like the many circles seen in Cyrenaica and in other parts of Northern Africa, evidently connected with the religious rites of the ancient inhabitants of these regions."[19] This is meagre enough; but fortunately, in addition to this, he observed and drew two monuments which are of equal and perhaps even of more importance to our present purposes.

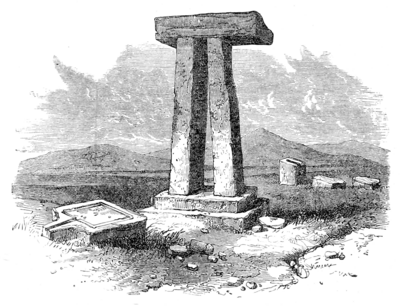

One of these, situated at a place called Ksaea, about forty-five miles east by south from Tripoli, consists of six pairs of trilithons, similar to that represented in the annexed woodcut. No plan is given of their arrangement, nor does Dr. Barth speculate as to their use; he only remarks that "they could never have been intended as doors, for the space between the upright stones is so narrow that a man of ordinary size could hardly squeeze his way between them."[20]

The other, situated at Elkeb, about the same distance from Tripoli, but south by east, is even more curious. It, too, is a trilithon, but the supports, which are placed on a masonry platform two steps in height, slope inwards, with all the appearance of being copied from a carpentry form, and the cap-stone likewise projects beyond the uprights in a manner very unusual in masonry. Another curious indication of its wooden origin is that the western pillar has three quadrangular holes on its inner side, 6 inches square, while the corresponding holes in the eastern pillar go quite through. These pillars are 2 feet square and 10 feet high, while the impost measures 6 feet 6 inches.[21]

In front of these pillars lies a stone with a square sinking in it and a spout at one side. Whatever this may have been intended for, it is—if the woodcut and description are to be depended upon—the exact counterpart of a Hindu Yoni, and as such would not excite remark as having anything unusual in its appearance if found in a modern temple at Benares. Beyond these in the woodcut are seen several other stones, evidently belonging to the same monument, one of which seems to have been formed into a throne.

These monuments are not, of course, alone. There must be others—probably many others—in the country, a knowledge of which might throw considerable light on our enquiries. In the meanwhile the first thing that strikes one is that Jeffrey of Monmouth's assertion, that "Giants in old days brought from Africa the stones which the magic arts of Merlin afterwards removed from Kildare and set up at Stonehenge,"[22] is not so entirely devoid of foundation as might at first sight appear. The removal of the stones is, of course, absurd, but the suggestion and design may possibly have travelled west by this route.

If we now turn back to page 100, it seems impossible not to The most curious point, however, connected with these monuments is the suggestion of Indian influence which they—especially that at Elkeb—give rise to. The introduction of sloping jambs, derived from carpentry forms, can be traced back in India, in the caves of Behar[23] and the Western Ghâts, to the second century before Christ, but certainly to no earlier date. The carpentry forms, but without the sloping jambs, continued at Sanchi and the Ajunta caves till some time after the Christian era, and where wood is used has, in fact, continued to the present day. "Mutatis mutandis," no two monuments can well be more alike to one another than that at Elkeb and the Buddhist tomb at Bangkok, represented in woodcut 177. The Siamese tomb may be a hundred years old; and if we allow the African trilithon to be late Roman, we have some fourteen or fifteen centuries between them, which, certainly, is as long as can reasonably be demanded. In reality it was probably less, but if the one was prehistoric, we lose altogether the thread of association and tradition that ought to connect the two.

To all this we shall have occasion to return, and then to discuss it more at length, when speaking of the Indian monuments and their connection with those of the West. In the meanwhile these two form a stepping-stone of sufficient importance to make us feel how desirable it is that the country where they are found should be more carefully examined. My impression is that the key to most of our mysteries is hidden in these African deserts.

- ↑ 'International Congress,' Norwich volume, 1869, p. 196.

- ↑ Norwich volume of 'Prehistoric Congress,' p. 196.

- ↑ A very imperfect one appeared in the 'Revue archéologique,' in 1865, vol. xi. pl. v. It contained most of the names of places where dolmens were then known to exist, but our knowledge has been immensely extended since then.

- ↑ 'Mémoires de la Soc. arch. de Constantine,' 1864, p. 127.

- ↑ Flower, in Norwich volume, p. 204.

- ↑ 'Mémoires, etc., de Constantine,' 1864, p. 124.

- ↑ Flower, in Norwich volume, pp. 201 et seqq.

- ↑ 'Mémoires, etc., de Constantine,' 1864, pp. 109, 114.

- ↑ 'Mémoires, etc., de Constantine.'

- ↑ Another is published by M. Bourguignal, in his 'Monuments symboliques de l'Algérie,' pl. i., but it is still more suspicious.

- ↑ I have been obliged to take some liberties with M. Féraud's cuts; the plan and elevation are so entirely discrepant, that one or both must be wrong. I have brought them a little more into harmony.

- ↑ 'Prehistoric Congress,' Norwich volume, p. 199.

- ↑ 'Mémoires, &c., de Constantine,' 1864.

- ↑ 'Revue archéologique,' viii. p. 527.

- ↑ Ibid. l. s. c.

- ↑ 'Mémoires, &c., de Constantine,' 1864, p. 122, pl. xxx.

- ↑ Flower, in Norwich volume, pp. 202-206.

- ↑ 'History of Architecture,' i. p. 81.

- ↑ 'Travels and Discoveries in Northern Africa,' i. p. 204.

- ↑ Ibid. p. 74.

- ↑ Ibid. p. 59. The holes are not shown in the cut.

- ↑ 'British History,' viii. chap. ii.

- ↑ 'History of Architecture,' by the Author, ii. p. 483.