Rude Stone Monuments in All Countries/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V.

IRELAND.

Moytura.

It is probable, after all, that it is from the Irish annals that the greatest amount of light will be thrown on the history and uses of the Megalithic monuments. Indeed, had not Lord Melbourne's Ministry in 1839, in a fit of ill-timed parsimony, abolished the Historical Commission attached to the Irish Ordnance Survey, we should not now be groping in the dark. Had they even retained the services of Dr. Petrie till the time of his death, he would have left very little to be desired in this respect. But nothing of the sort was done. The fiat went forth. All the documents and information collected during fourteen years' labour by a most competent staff of explorers were cast aside—all the members dismissed on the shortest possible notice, and our knowledge of the ancient history and antiquities of Ireland thrown back half a century, at least.[1]

Meanwhile, however, a certain number of the best works of the Irish annalists have been carefully translated and edited by John O'Donovan and others, and are sufficient to enable any one not acquainted with Irish to check the wild speculations of antiquaries of the Vallancy and O'Brien class, and also to form an opinion on the value of the annals themselves, though hardly yet sufficient to enable a stranger to construct a reliable scheme of chronology or history out of the heterogeneous materials presented to him. We must wait till some second Petrie shall arise, who shall possess a sufficient knowledge of the Irish language and literature, without losing his Saxon coolness of judgment, before we can hope to possess a reliable and consecutive account of ancient Ireland. When this is done, it will probably be found that the Irish possess a more copious literature, illustrative of the eocene period of their early history, than almost any other country of Europe. Ireland may also boast that, never having been conquered by the Romans, she retained her native forms, and the people their native customs and fashions, uninterrupted and uninfluenced by Roman civilization, for a longer time than the other countries of Europe which were subjected to its sway.

As most important and instructive parts of the Irish annals, it is proposed first to treat of those passages descriptive of the two battles of Moytura[2] (Magh Tuireadh), both of which occurred within a period of a very few years. A description of the fields on which they were fought will probably be sufficient to set at rest the question as to the uses of cairns and circles; and if we can arrive at an approximative date, it will go far to clear up the difficulties in understanding the age of the most important Irish antiquities.

The narrative which contains an account of the battle of Southern Moytura, or Moytura Cong, is well known to Irish antiquaries. It has not jet been published, but a translation from a MS. in Trinity College, Dublin, was made by John O'Donovan for the Ordnance Survey, and was obtained from their records above alluded to by Sir William Wilde. He went over the battle-field repeatedly with the MS. in his hand, and has published a detailed account of it, with sufficient extracts to make the whole intelligible.[3] The story is briefly this:—At a certain period of Irish history a colony of Firlolgs, or Belgæ, as they are usually called by Irish antiquaries, settled in Ireland, dispossessing the Fomorians, who are said to have come from Africa. After possessing the country for thirty-seven years, they were in their turn attacked by a colony of Tuatha de Dananns coming from the north, said to be of the same race and speaking a tongue mutually intelligible. On hearing of the arrival of these strangers, the Firbolgs advanced from the plains of Meath as far as Cong, situated between Longh Corrib and Lough Mask, where the first battle was fought, and, after being fiercely contested for four days, was decided in favour of the invaders.[4]

The second battle was fought seven years afterwards, near Sligo under circumstances which will be detailed more fully below, and resulted equally in favour of the Tuatha de Dananns, and they in consequence obtaiued possession of the country, which, according to the Four Masters, they held for 197 years.[5]

The field on which the four-days' battle of Southern Moytura was fought extends from five to six miles north and south. Near the centre of the space, and nearly opposite the village of Cong, is a group of five stone circles, one of which, 54 feet in diameter, is represented in the annexed woodcut (No. 54). Another, very similar, is close by; and a third, larger but partially ruined, is within a few yards of the first. The other two can only now be traced, and two more are said to have existed close by, but have entirely disappeared. On other parts of the battle-field there are six or seven large cairns of stone, all of them more or less ruined, the stones having been used to build dykes, with which every field is surrounded in this country; but none of them have been scientifically explored. One is represented (woodcut No. 55). Sir W. Wilde has identified all of these as connected with incidents in the battle, and there seems no reason to doubt his conclusions. The most interesting, however, is one connected with an incident in the battle, which is worth relating, as illustrating the manner in which the monuments corroborate the history. On the morning of the second day of the battle, King Eochy retired to a well to refresh himself with a bath, when three of his enemies looking down, recognised him and demanded his surrender. While he was parleying with them, they were attacked by his servant and killed; but the servant died immediately afterwards of his wounds, and, as the story goes, was interred with all honours in a cairn close by. In the narrative it is said that the well where the king had so narrow an escape is the only open one in the neighbourhood. It is so to the present day; for the peculiarity of the country is, that the waters from Lough Mask do not flow into Lough Corrib by channels on the surface, but entirely through chasms in the rock underground, and it is only when a crack in the rock opens into one of these that the water is accessible. The well in question is the only one of these for some distance in which the water is approached by steps partly cut in the rock, partly constructed. Close by is a cairn (woodcut No. 56), called to this day the "Cairn of the One Man." It was opened by Sir W. Wilde, and in its chamber was found one urn, which is now deposited in the Museum of the Royal Academy at Duhlin, the excavation thus confirming the narrative in the most satisfactory manner."The battle took place on Midsummer day. The Firbolgs were defeated with great slaughter, and their king, who left the battle- field with a body-guard of 100 brave men in search of water to allay his burning thirst, was followed by a party of 160 men, led by the three sons of Nemedh, who pursued him all the way to the strand, called Traigh Eothaile, near Ballysadare, in the county of Sligo. Here a fierce combat ensued, and King Eochy (Eochaidh) fell, as well as the leaders on the other side, the three sons of Nemedh."[6] A cairn is still pointed out on a promontory jutting into the bay, about a mile north-west of the village of Ballysadare, which is said to have been erected over the remains of the king, and bones are also said to have been found between high and low water on the strand beneath, supposed to be those of the combatants who fell in the final struggle. It may be otherwise, but there is a consistency between the narrative and the monuments on the spot which can hardly be accidental, and which it will be very difficult to explain except in the assumption that they refer to the same events.

In fact, it would be difficult to conceive anything more satis- factory and confirmatory of the record than the monuments on the plain; and no one, I fancy, could go over the field with Sir William's book in his hand, without feeling the importance of his identifications. Of course it may be suggested that the book was written by some one familiar with the spot, to suit the localities. The probability, however, of this having been done before the ninth century, and done so soberly and so well, is very remote, and the guess that but one urn would be found in the cairn of the "One Man," is a greater piece of luck than could reasonably be expected. Even, however, if the book was written to suit the localities, it will not invalidate the fact that a great battle was fought on this spot, and that these cairns and these circles mark the graves of those who fell in the fight.

The collection of monuments on the battle-field of Northern Moytura is even more interesting than that on Moytura Cong, and almost justified the assertion of Petrie "that, excepting the monuments at Carnac, in Brittany, it is, even in its present state of ruin, the largest assemblage of the kind hitherto discovered in the world."[7] They have also this advantage, that the principal group, consisting of some sixty or seventy monuments, are situated on an elevated table-land, and in an area extending not more than a mile in one direction, and about half a mile in another. The country, too, is much less stony than about Cong, so that the monuments stand out better and have a more imposing look. Petrie examined and described sixty-four monuments as situated in or around this space, and came to the conclusion that originally there could not have been less than 200.[8] My impression is that there may have been 100, but hardly more, though, of course, this is only a guess, and the destruction of them is going on so rapidly that he may be right after all.

In the space above described almost every variety of Megalithic art is to be found. There are stone cairns, with dolmens in their interiors—dolmens standing alone, but which have been evidently always exposed; dolmens with single circles; others with two or three circles of stones around them; and circles without dolmens or anything else in the centres. The only form we miss is the avenue. Nothing of the sort can now, at least, be traced, nor does it seem that any of the circles possessed such appendages.

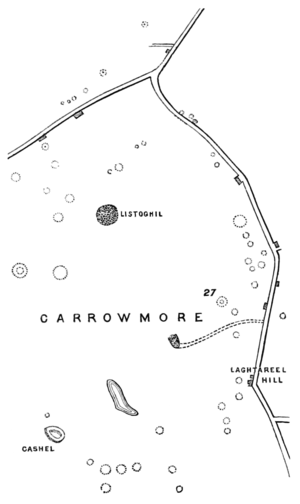

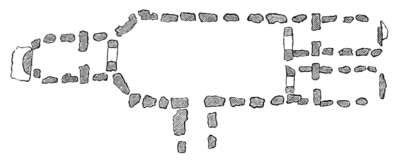

The annexed woodcut (No. 58) will explain the disposition of the principal group. It is taken from the Ordnance Survey, and is perfectly correct as far as it goes, but being only on the 6-inch scale, is too small to show the form of the monuments.[9] In the centre is, or rather was, a great cairn, called Listoghil. It is marked by Petrie as No. 51, but having for years been used as a quarry for the neighbourhood, it is now so mined that it is difficult to make out either its plan or dimensions. Petrie says it is 150 feet in diameter; I made it 120. It was surrounded by a circle of great stones, within which was the cairn, originally, probably, 40 or 50 feet high. All this has been removed to such an extent as to expose the kistvaen or dolmen in its centre. Its cap stone is 10 feet square and 2 feet thick, and is of limestone, as are its supports. All the other monuments are composed of granite boulders. "Those who first opened it assert that they found nothing within but burnt wood and human bones. The half-calcined bones of horses and other animals were and are still found in this cairn in great quantities" (Petrie, p. 250). In a note it is said that a large spear-head of stone (flint?) was also found in this cairn.

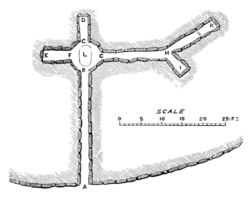

The annexed woodcut (No. 59) will give an idea of the general disposition of a circle numbered 27 by Petrie.[10] It is of about the medium size, being 60 feet in diameter. The general dimensions of the circles are 40, 60, 80, and one (No. 46) is 120 feet in diameter. The outer circle of No. 27 is composed of large stones, averaging 6 feet in height, and some 20 feet in circumference. Inside this is a circle of smaller stones, nearly obliterated by the turf, and in the centre is a three-chambered dolmen, of which fifteen stones still remain; but all the cap stones, except that of the central inner chamber, are gone, and that now stands on its edge in front of its support.

The general appearance of this circle will be understood from the annexed view (woodcut No. 60), taken from a photograph. It does not, however, do justice to its appearance, as the camera was placed too low and does not look into the circle, as the eye does. In the distance is seen the hill, called Knock na Rea, surmounted by the so-called Cairn of Queen Meave, of which more hereafter.

Another of these circles, No. 7, is thus described by Petrie:—"This circle, with its cromlech, are perfect. Its diameter is 37 feet, and the number of stones thirty-two. The cromlech is about 8 feet high, the table-stone resting on six stones of great magnitude: it is 9 feet long and 23 feet in circumference." Its general appearance will be seen in the annexed view from a photograph (woodcut No. 61); though this, as in the last instance, is far from doing justice to its appearance.[11]

No. 37 is described by Dr. Petrie (p. 248) as a triple circle. The inner one 40 feet in diameter. The second of twelve large stones, and of 80 feet, the third as a circle of 120 feet in diameter. "The cromleac is of the smallest size, not more than 4 feet in height. The circumference of the stone table is 16 feet, and it rests on five supporters."

Excavations were made into almost all these monuments either by Mr. Walker, the proprietor of the ground, or by Dr. Petrie, and, with scarcely one exception, they yielded evidence of sepulchral uses. Either human bones were found or urns containing ashes. No iron, apparently, was found in any. A bronze sword is said to have been found, forty years ago, in 63; but generally there was nothing but implements of bone or stone. At the time Petrie wrote (1837) these were not valued, or classified, as they have since been; so we cannot draw any inference from them as to the age of the monuments, and no collection, that I am aware of, exists in which these "finds" are now accessible. Indeed, I am afraid that Petrie and those who worked with him were too little aware of the importance of these material points of evidence, to be careful either to collect or to describe the contents of these graves; and as all or nearly all have been opened, that source of information may be cut off for ever.

Besides these monuments on the battle-field, there are two others, situated nearly equi-distant from it, and which seem to belong to the same group; one known as the Tomb of Misgan Meave, the celebrated Queen of Connaught, who lived apparently contemporaneously with Cæsar Augustus, or rather, as the annalists insist, with Jesus Christ;[12] though, according to the more accurate Tighernach, her death occurred in the 7th year of Vespasian, in A.D. 75.[13] It is situated on the top of a high hill known as Knock na Rea (woodcut No. 60), at a distance of two miles westward from the battle-field. It was described by the Rt. Hon. William Burton, in 1779, as an enormous heap of small stones, and is of an oval figure, 650 feet in circumference at the base, 79 feet slope on one side and 67 feet on the other. The area on the top is 100 feet in its longest diameter and 85 feet in its shortest. When Petrie visited it in 1837, it was only 590 feet in circumference, and the longest diameter on the top only 80 feet. It had in the interval, in fact, been used as a quarry; and I have no doubt but that the flat top originally measured the usual 100 feet, and was circular. "Around its base," says Petrie, "are the remains of many sepulchral monuments of lesser importance, consisting of groups of large stones forming circular or oval enclosures. A careful excavation within these tombs by Mr. Walker resulted in the discovery not only of human interments, but also of several rude ornaments and implements of stone of a similar character to those usually found in sepulchres of this class in Ireland, and which, being unaccompanied by any others of a metallic nature, identify this group of monuments as of contemporaneous age with those of Carrowmore, among which no iron remains are known to have been discovered, and mark them as belonging to any period of semi-civilized society in Ireland."[14]

From their situation, it seems hardly possible to doubt that these smaller tombs are contemporaneous with or subsequent to the Great Cairn; and if this really were the tomb of Queen Meave, it would throw some light on our subject. The great cairn has not, however, been dug into yet; and till that is done the ownership of the tomb cannot be definitely fixed. There are several reasons, however, for doubting the tradition. In the first place, we have the direct testimony of a commentary written by Moelmuiri, that Meave (Meahbh) was buried at Ratheroghan, which was the proper burying-place of her race; "her body having been removed by her people from Fert Medhbha; for they deemed it more honourable to have her interred at Cruachan."[15] As the Book of the Cemeteries confirms this, there seems no good reason for doubting the fact, though she may have first been laid in this neighbourhood, which may have given rise to the tradition.

If, on the other hand, we may trust Beowulf's description of a warrior's grave, as it was understood in the 5th century, no tomb in these islands would answer more perfectly to his ideal than the Cairn on Knock na Rea:—

"Then wrought

The people of the Westerns

A mound over the sea.

It was high and broad,

By the sea-faring man

To be seen afar."

That an Irish queen should be buried on a mountain-top over—looking the Western Ocean seems most improbable, and is opposed to the evidence we have; but that a Viking warrior should be so buried, overlooking the sea and a battle-field, seems natural; but who he may have been is for future investigators to discover.

The other cairn is situated just two miles eastward from the battle-field, on an eminence overlooking Loch Gill. It is less in height than the so-called Queen's Tomb, but the top is nearly perfect, and has a curious saucer-like depression, as nearly as can be measured, 100 feet in diameter. It has never been dug into, nor, so far as I could learn, does any tradition attach to it.

The history of the Battle of Northern Moytura, as told in the Irish Annals, is briefly as follows:[16]—

Nuada, who was king of the Tuatha de Dananns when the battle of Southern Moytura was fought, lost his arm in the fight. This, however, some skilled artificers whom he had with him skilfully replaced by one made of silver; so that he was always afterwards known as Nuada of the Silver Hand. Whether from this cause or some other not explained, he resigned the chief sovereignty to Breas, who, though a Fomorian by birth, held a chief command in the Tuatha de Danann army. Owing to his penurious habits and domineering disposition, Breas soon rendered himself very unpopular with the nobles of his Court; and, at a time when the discontent was at its height, a certain poet and satirist, Cairbré, the son of the poetess Etan, arrived at his Court. He was treated by the king in so shabby a manner and with such dis- respect, that he left it in disgust; but, before doing so, he wrote and published so stinging a satire against the king, as to set the blood of the nobles boiling with indignation, and they insisted on his resigning the power he had held for seven years. "To this call the regent reluctantly acceded; and, having held a council with his mother, they both determined to retire to the Court of his father Elatha, at this time the great chief of Fomorian pirates, or Sea Kings, who then swarmed through all the German Ocean and ruled over the Shetland Islands and the Hebrides."

Elatha agreed to provide his son with a fleet to conquer Ireland for himself from the Tuatha de Danann, if he could; and for this purpose collected all the men and ships lying from Scandinavia westwards for the intended invasion, the chief command being entrusted to Balor of the Evil Eye, conjointly with Breas. Having landed near Sligo, they pitched their tents on the spot—Carrowmore—where the battle was afterwards fought.

Here they were attacked by Nuada of the Silver Hand, accompanied by the great Daghda, who had taken a prominent part in the previous battle, and other chiefs of note. The battle took place on the last day of October, and is eloquently described. The Fomorians were defeated, and their chief men killed. King Nuada was slain by Balor of the Evil Eye, but Balor himself fell soon after by a stone flung at him by Lug his grandson by his daughter Eithlenn.

After an interval of forty years, ac3ording to the 'Annals of the Four Masters,' the Daghda succeeded to the vacant throne, and reigned eighty years.[17]

From the above abstract—all the important passages of which are in the exact words of the translation—it is evident that the author of the tract considered the Fomorians and the Tuatha de Danann as the same people, or at least as two tribes of the same race, the chiefs of which were closely united to one another by intermarriage. He also identifies them with the Scandinavian Vikings, who played so important a part in Irish history down to the Battle of Clontarf, which happaned in 1014.

This may at first sight seem very improbable. We must not, however, forget the celebrated lines of Claudian:[18] "Maduerunt Saxone fuso Orcades: incaluit Pictorum sanguine Thule: Scotorum cumulos flevit glacialis Ierne." This, it may be said, was written three or even four centuries after the events of which we are now speaking; but it was also written five centuries before the Northmen are generally supposed to have occupied the Orkneys or to have interfered in the affairs of Ireland, and does point to an earlier state of affairs, though how much anterior to the poet's time there is nothing to show.

It has been frequently proposed to identify the Dananns with the Danes, from the similarity of their names. Till I visited Sligo, I confess I always looked on this as one of those random guesses from identity of mere sound which are generally very deceptive in investigations of this sort. The monuments, however, on the battle-field correspond so nearly to those figured by Madsen in his 'Antiquités prehistoriques du Danemark,'[19] and their disposition is so similar to that of the Braavalla feld[20] and other battle-fields in Scandinavia, that it will now require very strong evidence to the contrary to disprove an obvious and intimate connection between them.

In concluding his account of the battle, Mr. O'Curry adds: "Cormac Mac Cullinan, in his celebrated Glossary, quotes this tract in illustration of the word Nes; so that so early as the ninth century it was looked upon by him as a very ancient historic composition of authority."[21] If this is so, there seems no good reason lor doubting his having spoken of events and things perfectly within his competence, and so we may consider the account above given as historical till at least some good cause is shown to the contrary.

It now only remains to try and find out if any means exist by which the dates of these two battles of Moytura can be fixed with anything like certainty. If we turn to the 'Annals of the Four Masters,' which is the favourite authority with Irish antiquaries, we get a startling answer at once. The battle of Moytura Cong, according to them, took place in the year of the world 3303, and the second battle twenty-seven years afterwards.[22] The twenty is a gratuitous interpolation. This is equivalent to 1896 and 1869 years before Christ. Alphabetical writing was not, as we shall presently see, introduced into Ireland till after the Christian Era, the idea therefore that the details of these two battles should have been preserved orally during 2000 years, and all the intermediate events forgotten, is simply ridiculous. The truth of the matter seems to be that the 'Four Masters,' like truly patriotic Irishmen in the middle of the seventeenth century, thought it necessary for the honour of their country to carry back its history to the Flood at least. As the country at the time of the Tuatha de Dananns was divided into five kingdoms,[23] and at other times into twenty-five, they had an abundance of names of chiefs at their disposal, and instead of treating them as cotemporary, they wrote them out consecutively, till they reached back to Ceasair—not Julius—but a granddaughter of Noah, who came to Ireland forty days before the Flood, with fifty girls and three men, who consequently escaped the fate of the rest of mankind, and peopled the western isle. This is silly enough, but their treatment of the hero of Moytura is almost as much so. Allowing that he was thirty years of age when he took so prominent a part in the second battle, in 3330, he must have been seventy-one when he ascended the Irish throne, and, after a reign of seventy-nine years, have died at the ripe old age of 150, from the effects of a poisoned wound he had received 120 years previously. The 'Four Masters' say eighty years earlier, but this is only another of their thousand and one inaccuracies.

When we turn from these to the far more authentic annals of Tighernach, who died 1088 A.D., we are met at once by his often quoted dictum to the effect that "omnia Monumenta Scotorum usque Cimboeth incerta erant."[24] It would have been more satisfactory if he could have added that after that time they could be depended upon, but this seems by no means to have been the case. As, however, Cimboeth is reported to have founded Armagh, in the year 289 B.C., it gives us a limit beyond which we cannot certainly proceed without danger and difficulty. We get on surer ground when we reach the reign of Crimthann, who, according to Tighernach, died in the year of our era 85, after a reign of 16 years.[25] The 'Four Masters,' it is true, make him contemporary with Christ; but even Dr. O'Donovan is obliged to confess that all these earlier reigns, after the Christian era, are antedated to about the same extent.[26] Unfortunately for our purpose, however, Tighernach's early annals are almost wholly devoted to the chronicles of the kings of Emania or Armagh, and it is only incidentally that he names the kings of Tara, which was the capital both of the Firbolgs and Tuatha de Dananns, and he makes no allusion to the battles of Moytura. Though our annalist, therefore, to a certain extent deserts us here, there are incidental notices of the Daghda and his friends in Irish manuscripts referring to other subjects, which seem sufficient to settle the question. The best of these were collected together for another purpose by Petrie, in his celebrated work on the Round Towers, and, as they are easily accessible there, it will not be necessary to quote them in extenso, but merely the passages bearing directly on our subject.[27]

The first extract is from a very celebrated work known as the 'Leabhar na l'Uidhre,' written apparently before 1106, which is given by the 'Four Masters' as the date of the author's death. Speaking of Cormac, the son of Art and grandson of Conn of a Hundred Battles:—"Before his death, which happened in 267, he told his people not to bury him at Brugh, on the Boyne, where the kings of Tara, his predecessors, were buried, because he did not adore stones and trees, and did not worship the same god as those interred at Brugh, for he had faith," adds the monkish chronicler, "in the one true God according to the law."

The tract then goes on to say that "the kings of the race of Heremon were buried at Cruachan until the times of Crimthann, who was the first king of them that was buried in Brugh." The others, including Queen Meave, were buried at Cruachan, because they possessed Connaught. "But they were interred at Brugh from the time of Crimthann to the time of Leoghaire, the son of Niall (A.D. 428), except three persons, namely Art the son of Conn, and Cormac the son of Art, and Niall of the Nine Hostages." A little further on we have the following paragraph:—"(101.) The nobles of the Tuatha de Danann were used to bury at Brugh, i.e., the Dagdha with his three sons, and also Lughaidh and Oe, and Ollam and Ogma, and Etan the poetess, and Corpre the son of Etan, and Crimthann followed them because his wife was one of the Tuatha Dea, and it was she that solicited him that he should adopt Brugh as a burying-place for himself and his descendants."

In the 'Book of Bally mote' (p. 102) it is said, "Of the monument of Brugh here, viz., The Bed of daughter of Forann. The monument of the Daghda. The mound of the Morrigan. The Bare of Crimthann in which he was interred. The Carnail (stone cairn) of Conn of a Hundred Battles," &c. In a second passage we recognise the following names rather more in detail: "The Bed of the Dagdha first, the two paps of the Morrigan, at the place where Cermud Milbhel, the son of the Dagdha was born[28]—(the monuments of) Cirr and Cuirrell wives of the Dagdha—there are two hillocks; the grave of Aedh Luirgnech, son of the Dagdha." Again, in a prose commentary on a poem which Petrie quotes, we have the following apparently by Moelmuori. The chiefs of Ulster before Conchobar (he is said to have died 33[29]) were buried at Talten . . . The nobles of the Tuatha de Dananns, with the exception of seven who were interred at Talten, were buried in Brugh, i.e., Lugh and Oe, son of Ollamh and Ogma, and Carpre the son of Etan, and Etan (the poetess herself), and the Daghda and her three sons, and a great many others besides of the Tuatha de Danann, Firbolgs, and others."

There is no doubt but that many similar passages to these might be found in Irish MSS., if looked for by competent scholars, but these extracts probably are sufficient to prove two things. First, that the celebrated cemetery at Brugh, on the Boyne, six miles west from Drogheda, was the burying-place of the kings of Tara from Crimthann (A.D. 84) till the time of St. Patrick (A.D. 432), and that it was also the burying-place of all those who were concerned—without being killed—in the battles of Moytura. We are not, unfortunately, able to identify the grave of each of these heroes, though it may be because only one has been properly explored, that called New Grange, and that had been rifled before the first modern explorers in the seventeenth century found out the entrance. The Hill of Dowth has only partially been opened. The great cairn of Knowth is untouched, so is the great cairn known as the Tomb of the Dagdha. Excavations alone can prove their absolute identity; but this at least is certain, we have on the banks of the Boyne a group of monuments similar in external appearance at least with those on the two Moytura battle-fields, and the date of the greater number of those at Brugh is certainly subsequent to the Christian era.[30]

The second point is not capable of such direct proof, but seems equally clear. It is that the kings of the race of Crimthann immediately succeeded to the kings of the Tuatha de Danann. who fought at Moytura. If, indeed, we could trust the assertion that Crimthann was the first king that was buried at Brugh, we should be obliged to find a place for the Daghda under some pseudonym afterwards, and it is possible that may be the case,[31] but for the present it seems more reasonable to assume that he preceded him at a very short interval.

According to the 'Four Masters,' the Tuatha de Danann had been extinct for nearly 2000 years when we find Crimthann marrying a princess of that race, and one of sufficient influence to induce him to adopt what appears literally to have been the family burying-place of the Dagdha for that of himself and his race; and it seems impossible to believe that when this took place it could have been old, or neglected, or deserted.

According to the 'Four Masters,' the Firbolgs reigned thirty-seven years only, so that they do not in this case seem to err on the side of exaggeration, and the Tuatha de Danann 196 years. From this, however, we must deduct the twenty years they un- necessarily interpolated between the two battles, and we must take something from the eighty years the Dagdha reigned after he was ninety-one years of age. If we allow, then, a century, it will place the battles of Moytura 20 to 30 B.C., and the arrival of the Firbolgs about the middle of the first century B.C. This, with a small limit of error either way is, I am convinced, pretty nearly the true date of these events.[32]

If we turn to the celebrated Hill of Tara, about ten miles off, where those resided who were buried at Brugh-na-Boinne, we find a great deal to confirm the views expressed above. When Petrie was attached to the Ordnance Survey, he had a very careful plan made of the remains on that hill, and compiled a most elaborate memoir regarding them, which was published in the eighteenth volume of the 'Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy.' It concludes with these words (p. 231): "From the historical allusions deduced it will be seen that, with the exception of the few last described,[33] they are all nearly contemporaneous and belong to the third century of the Christian era. The era of the original Tuatha de Danann Cathair belongs to the remote period of un- certain tradition. The only other monuments of ascertained date are those of Conor Mac Nessa and Cuchullim, both of whom flourished in the first century. These facts are sufficient to prove that before the time of Cormac Mac Art,[34] Tara had attained to no distinguished celebrity."

The only difficulty in this passage is the allusion to the Tuatha de Danann. At the time Petrie wrote it he, like most Irish antiquaries, had been unable to emancipate himself from the spell of the 'Four Masters,' and, struck by the pains they had taken, and the general correctness of their annals after the Christian era, had adopted their pre-Christian chronology almost without question. The Cathair here alluded to is only an undistinguishable part of the Rath of Cormac, to which tradition attaches that name, but neither in plan, nor materials, nor construction can be separated from it. That the Dananns had a Cathair on this hill is more than probable if, as I suppose, they immediately preceded the Crimthann dynasty, who certainly resided here. It may also well be that they occupied this site, which is the highest on the hill, and that their palace was afterwards enlarged by Cormac. The plan of it is worth referring to (woodcut No. 62), from its curious resemblance to that of Avebury; what was here done in earth was afterwards done in stone in Wiltshire, and it seems as if, as is so often the case, the house of the dead was copied from the dwelling of the living.The Dagdha had apparently no residence here. From the context I would infer that he resided in the great Rath, about 300 feet diameter, at Dowth, where his son, apparently, was born, and near to which, as above shown, he also was buried. If, however, he had no residence on the Royal hill, his so-called spit was one of the most celebrated pieces of furniture of the palace. It was a most elaborate piece of ironmongery, and performed a variety of cooking operations in a very astonishing manner, and shows, at all events, that the smith who made it had no little skill in the working of iron, of which metal it was principally composed.[35]

The Rath of Leoghaire (429-458 A.D.) is interesting to us, not only as the last erected here, but from the circumstances of its builder being buried in its ramparts. It seems that, in spite of all the preaching and persuasions of St. Patrick, who was his contemporary, Leoghaire refused to be converted to the Christian religion; but like a grand old Pagan, he ordered that he should be buried standing in his armour in the rampart of his Rath, and facing the country of the foes with whom he had contended during life. That this was done is as well authenticated as any incident of the time, perhaps even better;[36] and I cannot help fancying from the appearance of the Raths, that some others of the kings were interred here also. Be that as it may, this circumstance ought to prevent our feeling any surprise at the actual discovery of the skeleton of a man under the rampart at Marden (ante p. 86), or if human bones were still found under the vallum at Avebury, in spite of the negative evidence of the partial explorations of the Wiltshire Archæological Society.

There is still another point of view from which this question may be regarded, so as to throw some light on the main issue of the age of the monuments in question. If we can ascertain when the art of writing was first practised in Ireland, we may obtain an approximate date before which no detailed history of any events could be expected to exist. Now all the best antiquaries of Ireland are agreed that no alphabetic writing was used in Ireland before the reign of Cormac Mac Art, A.D. 218-266, There seems to be evidence that, as above mentioned, he was converted to Christianity by some Romish priest; and though it is unlikely that he himself acquired the art of writing, he seems to have caused certain tracts to be compiled. None of these, it is true, now exist, but they are referred to and quoted from an ancient Irish MS. in a manner that leaves little doubt that some books were written in Ireland in the third century, but almost certainly there were none before that time. It is true, however, that Eugene O'Curry pleads hard for some kind of Ogham writing having existed in Ireland before that time, and even before the Christian era.[37] But though we may admit the former proposition, the evidence of the latter is of the most unsatisfactory description. Even, however, if it could be established it would prove very little. It would be as difficult to write a connected history in Ogham as it would be in Exchequer tallies, and so far as is known, it never was attempted. The utmost Ogham ever did, or could do, was to record genealogies; and such detailed histories as we possess of the Moytura battles are quite beyond its powers. On the other hand, Mr. O'Curry's own account of Senchan's difficulties in obtaining copies of the celebrated 'Táin Bó Chuailgne,' or 'Cattle Spoil of Cooley,' after the year 598, shows how little the art was then practised. No copy of this poem, which contains the life and adventures of Queen Meave, in the first century, then existed in Ireland. A mission was consequently sent to Italy to copy one said to have existed there, and though the missionaries were miraculously spared the journey,[38] the inference is the same, that no written copy of their most celebrated work existed in Ireland in the year 600.

Petrie is equally clear on the subject. In his history of Tara he states that the Irish were unacquainted with letters till the introduction of Christianity in the fifth century, with the doubtful exception of the writings ascribed to Cormac Mac Art. He consequently believes that the authentic history of Ireland commences only with Tuathal, A.D. 130, 160, in which he is probably correct.[39] But here the question arises—Before the introduction of writing into a country, how long could so detailed a narrative as that which we possess of the Battles of Moytura, and one so capable of being verified by material evidences on the spot, be handed down orally as a plain prose narrative? Among so rude a people as the Irish avowedly then were, would this period be one century or two, or how many? Every one must decide for himself. I do not know an instance of any rude people preserving orally any such detailed history for a couple of centuries. With me the great difficulty is to understand how the memory of the battles was so perfectly preserved, assuming them to have taken place so long ago as the first century B.C. As it is not pretended that the narratives were reduced to writing so early as the time of Cormac, I should, from their internal evidence, be much more inclined to assume that the battles must have taken place one or two centuries after the birth of Christ. At all events, it seems absolutely impossible that the date of these battles can be so remote as the Four Masters place them, or even as some Irish antiquaries seem inclined to admit.

The truth of the matter appears to be that, in the Eocene period of Irish history or in the one or two centuries that preceded the introduction of writing, we have a whole group of names so inextricably mixed together that it is impossible to separate them. We have the Dagdha and his wives and their sons. We have Etan the poetess and her ill-conditioned son. There is Queen Meave of the Cattle Raid, and her husband Conchobhar McNessa. There is Cumbhail, the Fingal of Macpherson and Cuchullin; and then such semi-historical persons as Tuathal the Accepted, and Conn of a Hundred Battles. All these lived almost together in one capital, and were buried in one cemetery, and form a half-historic, half-mythic group, such as generally precedes written history in most parts of the world. Many of their dates are known with fairly approximate certainty, whilst that of others cannot be fixed. There seems, however, enough to justify us in almost positively affirming that the Battle of Moytura, which raised the Dagdha to fame, happened within the fifty years that preceded or the fifty that followed the birth of Christ. My own impression is in favour of the former as the more probable date.

To some this may appear an over-laboured disquisition to prove an insignificant point. It is not, however, one-tenth part of what might be advanced on the subject from translated and printed documents, and, certainly, it would be difficult to exaggerate its importance with reference to the subject matter of this work. If the two groups of monuments at Cong and Carrowmore can be proved to be the monuments of those who fell in the two battles of Southern and Northern Moytura, we have made an immense step towards a knowledge of the use of these monuments; and if it can be shown that they date from about the Christian Era, we gain not only a standpoint for settling the age of all other Irish antiquities, but a base for our reasoning with reference to similar remains in other countries.

No Irish antiquary, nor indeed of any other country, so far as I know, has ventured to hint a doubt that they mark the battle-fields. Nor, in the present state of the evidence, do I see any reason for questioning the fact; and, for the present at least, we may assume it as granted. The second proposition is more open to question. Irish antiquaries generally will dissent from so serious a reduction in the antiquity of these two great battles. But, after the most earnest attention I have been able to give to all that has been written and said on the subject and a careful comparison of the monuments on these fields with those of other countries, I would, on the whole, be inclined to bring them forward a century or two, if I could find a gap to throw them into, rather than date them earlier. They look older and more tentative than the English circles described in the last chapter, but not so much so as to lead us to expect a difference of four or five centuries. On the other hand, they are so like those on the Bravalla field, and other monuments in Scandinavia, to be described hereafter, that it is puzzling to think that seven or ten centuries elapsed between them. But, taking all the circumstances of the case into consideration, the conclusions above arrived at appear fair and reasonable, and in conformity, not only to what was said in the last chapter, but to the facts about to be adduced in the following pages.

Cemeteries.

Although Irish antiquaries have succeeded in identifying the localities of a considerable number of the thousand and one battles which, as might be expected, adorn at every page the annals of a Celtic race; yet, as none of these are described as marked with circles or cairns, like those found on the two battle-fields of Moytura, they are of no use for our present purpose, and our further illustrations must be drawn from the peaceful burying-places of the Irish, which are, however, of singular interest.

In the history of the Cemeteries, eight are enumerated;[40] but of these only the first three can be identified with anything like certainty at the present day. But as the antiquities of Ireland have never yet been systematically explored, others may yet be found, and so also may many more stone-marked battle-fields. Meanwhile our business is with

"The three cemeteries of the idolaters:

The Cemetery of Tailten the select,

The Cemetery of the ever fair Cruachan,

And the Cemetery of Brugh."[41]

The two last are known with certainty. The first is most probably the range of mounds at Lough Crew, recently explored by Mr. Conwell; but, as some doubt this identification, we shall take it last, and speak first of those regarding which there is more certainty.

Cruachan, or Rathcrogan, is situated five miles west from Carrick-on-Shannon, and consists, according to Petrie, of a circular stone ditch,[42] now nearly obliterated, 300 feet in diameter. Within this "are small circular mounds, which, when examined, are found to cover rude sepulchral chambers, formed of stone, without cement of any kind, and containing unburnt bones." The monument of Dathi (428 A.D.), which is a small circular mound with a pillar-stone of Red Sandstone, is situated outside the enclosure, at a short distance to the east, and maybe identified from the following notice of it by the celebrated antiquary Duald Mac Firbis. "The body of Dathi was brought to Cruachan, and was interred at Relig na Riogh, where most of the kings of the race of Heremon were buried, and where to this date the Red Stone pillar remains on a stone monument over his grave, near Rath Cruachan, to this time (1666).[43]

Here, therefore, we have the familiar 300-foot circle, with the external burial, as at Arbor Low, and external stone monument as at Salkeld and elsewhere. The chief distinction between this and our English battle-circles seems to be the number of cairns, each containing a chamber, which crowd the circle at Rath Crogan, and it is possible that if these were opened with great care, a succession might be discovered among them; but at present we know little or nothing of their contents.

At present there are only two names that we can identify with certainty as those of persons buried here. Queen Meave, who, as before mentioned, was transferred from Fert Meave—or Meave's Grave, her first burying-place, to this Rath, about the end of the first century, and Dathi, at the beginning of the fifth. Whether any other persons were interred here before the first-named queen seems doubtful. From the context, it seems as if her being buried in her own Rath had led to its being consecrated to funereal rites, and continuing to be so used till Christianity induced men to seek burying-places elsewhere than in the cemeteries of the idolaters.

By far the best known, as well as the most interesting, of Irish cemeteries is that which extends for about two miles east and west on the northern bank of the Boyne, about five miles from Drogheda. Within this space there remain even now some seventeen sepulchral barrows, three of which are pre-eminent.[44] They are now known by the names of Knowth for the most westward one, Dowth for that to the east, and about half-way between these two, that known as New Grange. In front of the latter, but lower down nearer the river, is a smaller one, still popularly known as that of the Dagdha, and others bear names with more or less certainty; but no systematic exploration of the group has yet been made, so that we are very much in the dark as to their succession, or who the kings or nobles may be that lie buried within their masses.

That at Knowth has never been carefully measured, nor, so far as I know, even described in modern times. At a guess, it is a mound 200 feet in diameter, and 50 to 60 feet in height, with a flat top not less than 100 feet across. It is entirely composed of small loose stones, which have been extensively utilized for road making and farm buildings, so that the mound has now a very dilapidated appearance, which makes it difficult to ascertain its original form; and so far as is known, its interior has not been accessible in modern times. Petrie identifies it (p. 103) with "the cave of Cnodhba, which was searched by the Danes on an occasion (A.D. 862), when the three kings, Amlaff, Imar, and Auisle, were plundering the territories of Flann, the son of Conaing. If this is so, its entrance ought not to bo difficult to find, but the prospect of the explorers being rewarded by any treasure or object of value is very small indeed.

Less than a mile from this one is the larger and more celebrated mound of New Grange. It is almost certainly one of the three plundered by the Danes 1009 years ago. No description of it has anywhere been discovered, prior to the time when Mr. Llwyd, the keeper of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, mentioned it in a letter dated Sligo, 1699.[45] He describes the entrance, the passage, and the side chapels, and the three basins as existing then exactly as they do now, and does not allude to the discovery of the entrance as being at all of recent occurrence, though Sir Thomas Molyneux, in 1725, says it was found apparently not long before he wrote, in accidently removing some stones.[46] The first really detailed account, however, is that of Governor Pownall, in the second volume of the 'Archæologia' (1770). He employed a local surveyor of the name of Bouie to measure it for him, but either he must have been a bungler, or the engraver has mis- understood his drawings, for it is almost impossible to make out the form and dimensions of the mound from the plates published. In the 100 years that have elapsed since his survey was made, the process of destruction has been going on rapidly, and it would now require both skill and patience to restore the monument to its previous dimensions. Meanwhile the accompanying cuts, partly from Mr. Bouie's plates, partly from personal observations, may be sufficient for purposes of illustration, but they are far from pretending to be perfectly accurate, or such as one would like to see of so important a monument.

Its dimensions, so far as I can make out, are as follows: it has a diameter of 310 to 315 feet for the whole mound, at its junction with the natural hill, on which it stands. The height is about 70 feet, made up of 14 feet for the slope of the hill to the floor of the central chamber, and 56 feet above it. The angle of external slope appears to be 35 degrees, or 5 degrees steeper than Silbury Hill, and consequently if there is anything in that argument, it may, at least, be a century or two older. The platform on the top is about 120 feet across, the whole being formed of loose stones, with the smallest possible admixture of earth and rubbish.

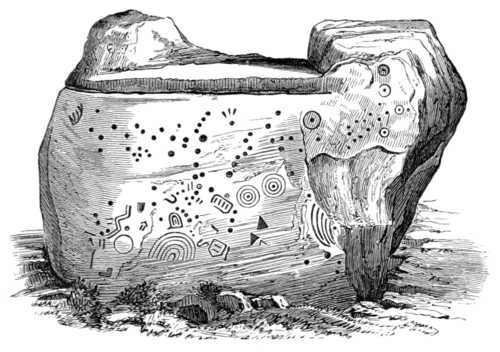

Around its base was a circle of large stone monoliths (woodcut No. 63). They stand, according to Sir W. Wilde, 10 yards apart, on a circumference of 400 paces, or 1000 feet. If this were so, they were as nearly as may be 33 feet from centre to centre, and their number consequently must originally have been thirty, or the same number as at Stonehenge. From Bouie's plan I make the number thirty-two, but this is hardly to be depended upon. From this disposition it will be observed that if the tumulus were removed, or had never been erected, we should have here exactly such a circle—333 feet in diameter—as we find at Salkeld or at Stanton Drew, and it seems hardly doubtful but that such an arrangement as this on the banks of the Boyne gave rise to those circles which we find on the battle-fields of England two or three centuries later. Llwyd, in his letter to Rowland, mentions one smaller stone standing on the summit, but that had disappeared, as well as twenty of the outer circle, when Mr. Bouie's survey was made.At a distance of about 75 feet from the outer edge of the mound, and at a height of 14 or 15 feet above the level of the stone ring, is the entrance to the crypt. The threshold stone is 10 feet long by about 18 inches thick, and is richly ornamented by double spirals of a most elaborate and elegant character;[47] and at a short distance above it is seen a fragment of a string-course, even more elaborately ornamented with a pattern more like modern architecture than anything else on these mounds. The passage into the central chamber is, for about 40 feet, 6 feet high, by 3 feet in width, though both these dimensions have been considerably diminished, the first by the accumulation of earth on the floor, the second by the mass of the mound pressing in the side walls of the passage, so that it is with difficulty that any one can crawl through. Advancing inwards, the roof, which is formed of very large slabs of stone, rapidly becomes higher; and at a distance of 70 feet from the entrance, rises into a conical dome 20 feet in height, formed of large masses of stone laid horizontally. The crypt extends still 20 feet beyond the centre of the dome; and on the east and west sides are two other recesses, that in the east being considerably deeper than the one opposite to it.

In each of these recesses stands a shallow stone basin of oval form 3 feet by 3 feet 6 or 7 inches across, and 6 to 9 inches deep. They seem to form an indispensable part of these Irish sepulchres, though what their use was has not yet been ascertained.

On one stone in the passage, and on most of those in the inner chamber, are sculptured ornaments, mostly of the same spiral character as that on the stone at the threshold, but hardly so elaborately or carefully executed. One stone on the right hand angle of the inmost chamber has fallen forward (see plan), so that by creeping behind it, it is possible to see the reverse of some of the neighbouring stones, and it is found that several of these are elaborately carved with the same spiral ornaments as their fronts, though it is quite impossible that, situated as they are, they could have been seen after the mound was raised. To account for this, some have asserted that they belonged to an older building before having been used in this; but it hardly seems necessary to adopt so violent an hypothesis. It may have been that the stones were carved before being used, and at a time when no plans or drawings existed, may have been found unsuited in size or form for the places for which they were first intended, and consequently either turned round or used elsewhere. Or it may be that as the crypt must have been built and tolerably complete before the mound was raised over it, the king may have had it ornamented externally while in that state. Labour was of little value in those days, and it is dangerous to attempt to account for the caprices of kings in such a state of society as must then have existed. The identity of the style and character of the ornaments both on the hidden and the visible parts of these stones excludes the idea that they were the work of different epochs. A removal from an older building implies a desecration and neglect which must have been the work of time; and, having regard to their identity, it is improbable that a time considerable enough would have elapsed to admit of a building being so desecrated and neglected as that its stones should be carried away and used elsewhere.

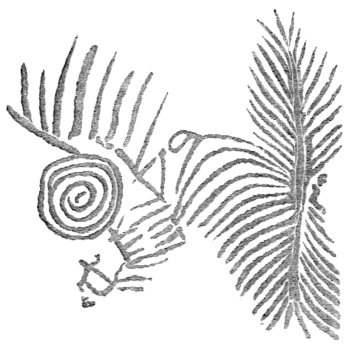

The position of the entrance so much within the outline of the Tumulus, is a peculiarity at first sight much more difficult to account for. As it now stands, it is situated at a distance of about 50 feet horizontally within what we have every reason to believe was the original outline of the mound. Not only is there no reasou to believe that the passage ever extended further, but the ornamented threshold, and the carved string- course above, and other indications, seem to point out that the tumulus had what may be called an architectural facade at this depth. One mode of accounting for this would be to assume that the original mound was only about 200 feet in diameter at the floor level, and that the interior was then accessible, but that after the death of the king who erected it, an envelope 50 feet thick was added by his successors, forming the broad platform at the top, and effectually closing and hiding the entrance to the sepulchre. If this were so, we may easily fancy that many of his family, or of his followers, were buried in this envelope, and formed the secondary but nearly contemporary interments which are so frequently found in English mounds. The experience of Minning Lowe (woodcut No. 33), Rose Hill (woodcut No. 39), and other English tumuli, goes far to countenance such an hypothesis; and there is much besides to be said in its favour, but it is one of those questions which can only be answered satisfactorily by a careful examination of the mound itself. Meanwhile, however, I am rather inclined to adopt the hypothesis that the mound had a funnel-shaped entrance like Park Cwn tumulus (woodcut No. 46), and that at Plas Newydd (woodcut No. 47), and shown in dotted lines in the woodcut No. 64. The reason for this will be more apparent when we come to examine the Lough Crew tumuli, but the apparent ease with which Amlaff and his brother Danes seem to have robbed these tombs in the ninth century, seems to indicate that the entrances were not then difficult to find.The ornaments which cover the walls of the chambers at New Grange are very varied, both in their form and character. The most prevalent design is that of spirals variously combined, and often of great beauty. They seem always to have been drawn by the hand, never outlined with an instrument, and never quite regular either in their form or combination. The preceding woodcuts from rubbings give a fair idea of their general appearance, though many are much more complex, and some more carefully cut. The most extensive, and perhaps also the most beautiful, is that on the external doorstep.[48] These spirals are, however, seldom alone, but more frequently are found eombiced with zigzag ornaments, as in (woodcut No. 66), and in lozenge-shaped patterns; in fact, in every conceivable variety that seemed to suit the fancy of the artist, or the shape of the stone he was employed upon. In one instance a vegetable form certainly was intended. There may be others, but this one most undoubtedly represents either a palm branch or a fern; my impression is that it is the former, though how a knowledge of the Eastern plant reached New Grange is by no means clear. One other example of the sculptures is worth quoting, if not for its beauty, at least for its interest (woodcut No. 68). It is drawn full size in the second volume of the 'Archæologia,' p. 238, and Governor Pownall, after a learned disquisition, concludes that the characters are Phœnician but only numerals (p. 259). General Vallancey and others have not been so modest; but one thing seems quite clear, that it is not a character in any alphabet now known. Still it can hardly be a mere ornament. It must be either a mason's mark, or a recognizable symbol of some sort, something to mark the position of the stone on which it is engraved, or its ownership by some person. Similar marks are found in France, but seem there equally devoid of any recognizable meaning.

The third of these great tumuli on the Boyne is known as that of Dowth. Dubhad if Petrie is right in identifying it with the third sepulchre plundered by the Danes in 862. It was dug into by a Committee of the Royal Irish Academy in 1847, but without any satisfactory results, A great gash was made in its side to its centre, which has fearfully disfigured its form,[49] but without any central chamber being reached; but on the western side a small entrance was discovered leading to a passage which extended 40 feet 6 inches (from A to D) towards the interior. At the distance of 28 feet from the entrance it formed a small domical chamber, with three branches, very like that at New Grange, but on a smaller scale. In the centre of this apartment was one large flat basin (L), similar in form, and, no doubt, in purpose, to the three at New Grange, but far larger, being 5 feet by 3 feet. The southern branch of the chamber extends to K in a curvilinear form for about 28 feet, where it is stopped for the present by a large stone, and another partially obstructs the passage at 8 feet in front of the terminal stone.

The Academy have not yet published any account of their diggings, nor does any plan of the mound exist, eo far as I know, anywhere. Even its dimensions are unknown. Pendinir these being ascertained, it does look as if this cliamber was in an envelope similar to that just suggested as having existed at New Grange. In that case the original tumulus was probably 120 feet in diameter, and with its envelope 200 feet.

The walls of the chambers of this tomb are even more richly and elaborately ornamented than those of the chambers at New Grange, and are in a more delicate style of workmanship. Altogether I should be inclined to consider it as more modern than its more imposing rival.

One other small tumulus of the cemetery is open. It is situated in the grounds of Netterville House. It is, however, only a miniature repetition of the central chambers of its larger compeers, but without sculptures or any other marked peculiarity.

The mound called the Tomb of the Dagdha and the ten or twelve others which still exist in this cemetery, are all, so far as is known, untouched, and still remain to reward the industry of the first explorer. If the three large mounds are those plundered by the Danes, which seems probable, this is sufficient to account for the absence of the usual sepulchral treasures, but it by no means follows that the others would be equally barren of results. On the contrary, there being no tradition of their having been opened, and no trace of wounds in their sides, we are led to expect that they may be intact, and that the bones and armour of the great Dagdha may still be found in his honoured grave.

Nothing was found in the great mounds at New Grange and Dowth which throws much additional light either on their age or the persons to whom they should be appropriated. Two skeletons are said to have been discovered at New Grange, but under what circumstances we are not told, and we do not consequently know whether to consider them as original or secondary interments. The finding of the coin of Valentinian is mentioned by Llwyd in 1699, but he merely says that they were found on the top, or rather, as might be inferred, near the top, when it was uncovered by the removal of the stones for road-making and such purposes. Had it been found in the cell, as at Minning Low, it would have given us a date, beyond which we could not ascend, but when and under what circumstances the coin of Theodosius was found, does not appear, nor what has become of either. A more important find was made by Lord Albert Cunyngham in 1842. Some workmen who were employed to dig on the mound near the entrance discovered two splendid gold torques, a brooch, and a gold ring, and with them a gold coin of Geta[50] (205-212 A.D.). A similar gold ring was found about the same time in the cell, and is in the possession of Mrs. Caldwell, the wife of the proprietor. Although we might feel inclined to hesitate about the value of the conclusions to be drawn from the first discovery of coins, this additional evidence seems to he conclusive. Three Roman coins found in different parts, at diiferent times, and with the torques and rings, are, it seems, quite sufficient to prove that it cannot have been erected before 380, while the probable date for its completion may be about 400 A.D. It may, however, have been begun fifty or sixty years earlier. It is most likely that such a tomb as this was commenced by the king whose remains it was destined to contain; but the mound would not be heaped over the chamber till the king himself, and probably his wives and sons, were laid there, and a considerable period may consequently have elapsed between the inception and the completion of such a monument.

At Dowth there was the usual miscellaneous assortment of things. A great quantity of globular stone-shot, probably sling- stones; and in the chamber fragments of burned bones, many of which proved to be human; glass and amber beads of unique shape, portions of jet bracelets, a curious stone button, a fibula, bone bodkins, copper pins, and iron knives and rings. Some years ago a gentleman residing in the neighbourhood cleared out a portion of the passage, and found a few iron antiquities, some bones of mammals, and a small stone urn, which he presented to the Irish Academy.[51] In so far as negative evidence is of value, it may be remarked that no flint implements and nothing of bronze—unless the copper pins are so classed—was found in any of these tumuli.

The ornaments found inside the chambers at Dowth are similar in general character to those at New Grange, but, on the whole, more delicate and refined. Assuming the progressive nature of Irish art, which I see no reason for doubting, they would indicate a more modern age, and this, from other circumstances, seems more than probable. Though spirals are frequent, the Dowth ornaments assume more of free-traced vegetable forms. It is not so easy to identify the figures in the annexed woodcut (No. 70), as in the palm-branch in New Grange (woodcut No. 67), but there can be little doubt that the intention was to simulate vegetable nature. At other times forms are introduced which a fanciful antiquary might suppose were intended for serpents, or writing, or, at all events, as having some occult meaning. The annexed from a rubbing is curious, as something very similar occurs on a stone at Coilsfield, in Ayrshire, and may really be intended to suggest an idea, but of what nature we are not yet in a position to guess. It is not so like an alphabetical character as those at New Grange (woodcut No. 68), and till that is shown to have a meaning, it is hardly worth while speculating with regard to this one. We shall be in a better position to judge of the value or importance of these ornaments, in an artistic or chronometric point of view, when we have examined those at Lough Crew and elsewhere; but even irrespectively of such considerations, no one can examine the monuments on the banks of the Boyne without being struck with the elegance as well as the endless variety of the ornaments which cover their walls.If, however, the material proofs are deficient, the written evidence is clearer and more satisfactory than with regard to any group of tombs in the three kingdoms. In the passage above quoted, it is said "that they"—the kings of Ireland—"were interred at Brugh from the time of Crimthann (A.D. 76) to the time of Leoghaire, the son of Niall (A.D. 458), except three persons, namely, Art the son of Conn, and Cormac the son of Art, and Niall of the nine hostages,"—the father of Leoghaire. The reason given why Art and Cormac were not buried here was that they had embraced Christianity. Art was buried at a place called Treoit; Cormac on the right bank of the Boyne at a place called Kos-na-righ, opposite Brugh; and Niall at Ochaim. But having disposed of these three, we have still some twenty-seven kings to find graves for, and only seventeen mounds can now be traced at Brugh; and, besides these, we have to find the tombs of the Dagdha, and his three sons, and Etan the poetess and her son Corpre, and Boinn, the wife of Nechtan, "who took with her to the tomb her small hound Dabilla," and a vast number of nobles of Tuatha de Danann and others. It is impossible to find places for all these persons in the graves now visible, if each was buried separately. It may be, however, that the great mounds contained several sepulchres. The form and position of the chambers at Dowth (woodcut No. 69) perhaps countenances such a supposition; but many may have been buried under smaller cairns, long since removed to make way for agricultural improvements, and many may yet be discovered if the place be carefully and systematically explored, which does not yet seem to have been done. Before, however, anything like certainty could be arrived at as to the distribution of these graves, it would be necessary that the great mounds should be thoroughly explored, and this, from the nature of their material, will practically involve their destruction, which would be very much to be regretted. Mean- while, if I may be allowed to offer a conjecture, I would say that New Grange might be the "Cumot or Commensurate grave of Cairbre Lifeachair." He, according to the Four Masters, reigned from 271 to 288—but probably fifty or sixty years later—and seems to have been a king deserving of a right royal sepulchre; and I feel great confidence that the unopened tumulus near the river may be what tradition says it is—the grave of the Great Dagdha, the hero of Moytura. With regard to the others, it would not be safe to hazard any opinion in the present state of our knowledge. For the present it is sufficient to feel sure that we have a group of monuments all, or very nearly all of which were erected in the first four centuries of the Christian era, and from this basis we may reason with tolerable certainty regarding the other groups which we may meet with in the course of this enquiry.

Lough Crew.

At a distance of twenty-five miles nearly due west from Brugh na Boinn, and two miles south-east from Oldcastle, is a range of hills, called on the Ordnance map Slieve na Calliagh—the hags' or witches' hill. It is upwards of 200 feet above the level of the sea, and the most conspicuous elevation in that part of the country. On the ridge of this range, which is about two miles in extent, are situated from twenty-five to thirty cairns, some of considerable size, being 120 to 180 feet in diameter; others are much smaller, and some so nearly obliterated that their dimensions can hardly be now ascertained. Till seven or eight years ago this cemetery was entirely unknown to Irish antiquaries, and the positions of the cairns were hardly even indicated in the Ordnance Survey; but in 1863 they attracted the attention of Mr. Eugene Conwell, of Trim. In the years 1867-8 he was enabled, with the assistance and co-operation of the late Mr. Naper, of Lough Crew, the proprietor of the soil, to excavate and explore the whole of them. A brief account of the results which he obtained was submitted to the Royal Irish Academy in 1868, and afterwards printed by him for private circulation in 1868; but the greater work, with plans and drawings, in which he intends fully to illustrate the whole, is still in abeyance, owing to want of encouragement. When completed it will be one of the most valuable contributions to our archæological knowledge that we have received of late years. Meanwhile the following meagre particulars are derived from Mr Conwell's pamphlet and the information I picked up during a personal visit which I made to the spot in his company in the Autumn of last year. The illustrations are all from his drawings.

One of the most perfect of these tumuli is that distinguished by Mr. Conwell as Cairn T (woodcut No. 72). It stands on the highest point of the hill, and is consequently the most conspicuous. It is a truncated cone, 116 feet in diameter at base, and with a sloping side, between 60 and 70 feet in length. Around its base are thirty-seven stones, laid on edge, and varying from 6 to 12 feet in length. They are not detached, as at New Grange, but form a retaining wall to the mound. On the north, and set about 4 feet back from the circle, is a large stone, 10 feet long by (5 high, and 2 feet thick, weighing consequently above 10 tons. The upper part is fashioned as a rude seat, from which it derives its name of the Hag's Chair (woodcut No. 73), and there can be little doubt but that it was intended as a seat or throne; but whether by the king who erected the sepulchre, or for what purpose, it is difficult now to say.

On the eastern side of the mound the stones forming the periphery of the cairn curve inwards for eight or nine yards on each side of the spot where the entrance to the chamber commences. It is of the usual cruciform plan, and 28 feet long from the entrance to the flat stone closing the innermost cell; the dome, consequently, is not nearly under the centre of the tumulus, as at New Grange, and lends something like probability to the notion that the cell at Dowth (woodcut No. 69), was really the principal sepulchre. Twenty-eight of the stones in the chamber were ornamented with devices of various sorts. Two of them are represented on the ac- companying woodcut (No. 74), which, with the drawings on the Hag's Chair give a fair idea of their general character. They are certainly ruder and less artistic than those on the Boyne, and so far would indicate an earlier age. Nothins was found in the chambers of this tomb but a quantity of charred human bones, perfect human teeth, mixed with the bones of animals, apparently stags, and one bronze pin, 21/2 inches long, with a head ornamented and stem slightly so, and still preserving a beautiful green polish.

Cairn L (woodcut No. 75), a little further west, is 135 feet in diameter, and surrounded by forty-two stones, similar to those in Cairn T. The same curve inwards of these stones marks the entrance here, which is placed 18 feet from the outward line of the circle. The chamber here is nearly of the same dimensions as that last described, being 29 feet deep and 13 across its greatest width. In one of the side chambers lies the largest of the mysterious flat basins that have yet been discovered, 5 feet 9 inches long by 3 feet 1 inch broad, the whole being tooled and picked with as much care and skill as if executed by a modern mason. This one has a curious nick in its rim, but as it does not go through, it could hardly be intended as a spout. Till some unrifled tomb is found, or something analogous in other countries, it is extremely difficult to say what the exact use of these great stone saucers may have been. That the body or ashes were laid on them is more than probable, and they may then have been covered over with a lid like a dish-cover, such as are found on tombs in Southern Babylonia.[52] Under this basin were found great quantities of charred human bones and forty-eight human teeth, besides a perfectly rounded syenite ball, still preserving its original polish, also some jet and other ornaments. In other parts were found quantities of charred bones, some rude pottery and bone implements, but no objects in metal. The woodcut representing the cell, with large basin, gives a fair idea of the general style of sculpture in this and the neighbouring cairns. The parts cross-hatched seem to have been engraved with a sharp metal tool. The ordinary forms, however, both here and on the Boyne are picked; but whether they were executed with a hammer, or pick direct, or by a chisel driven by a hammer, is by no means clear. My own impression is, that it would be very difficult indeed to execute these patterns with a hammer of any sort, and that a chisel must have been used, but whether of flint, bronze, or iron, there is no evidence to show.

Cairn H, though only between 5 and 6 feet in height and 54 feet in diameter, seems to have been the only one on the hill not previously rifled, and yielded a most astonishing collection of objects to its explorer. The cell was of the usual cruciform plan, 24 feet from the entrance to the rear, and 16 feet across the lateral chambers. In the passage and crypts of this cairn Mr. Conwell collected some 300 fragments of human bones, which must have belonged to a considerable number of separate individuals; 14 fragments of rude pottery, 10 pieces of flint, 155 sea-shells in a perfect condition, besides pebbles and small polished stones, in quantities.

The most remarkable part of the collection consisted of 4884 fragments, more or less perfect, of bone implements. These are now in the Dublin Museum, and look like the remains of a paper-knife-maker's stock-in-trade. Most of them are of a knife shape, and almost all more or less polished, but without further ornamentation; but 27 fragments appear to have been stained, 11 perforated, 501 engraved with rows of fine lines; 13 combs were engraved on both sides, and 91 engraved by compass with circles and curves of a high order of art. On one, in cross-hatch lines, is the representation of an antlered stag, the only attempt to depict a living thing in the collection.

Besides these, there were found in this cairn seven beads of amber, three small beads of glass of different colours, two fragments, and a curious molten drop of glass, 1 inch long, trumpet-shaped at one end, and tapering towards the other extremity; six perfect and eight fragments of bronze rings, and seven specimens of iron implements, but all, as might be expected, very much corroded by rust. One of these presents all the appearance of being the leg of a compass, with which the bone implements may have been engraved, and one was an iron punch, 5 inches long, with a chisel-shaped point, bearing evidence of the use of the mallet at the opposite end.

Cairn D is the largest and most important monument of the group, being 180 feet in diameter, and though it is very much dilapidated, the circle of fifty-four stones which originally surrounded it can still be traced. On its eastern side the stones curve inwards for about twelve paces, in the form universal in these cairns; but though the explorers set to work industriously to follow out what they considered a sure "find," they could not penetrate the mound. The stones fell in upon them so fast, and the risk they ran was so great, that they were forced to abandon the idea of tunnelling, and though a large body of men worked assiduously for a fortnight trying to work down from above, they failed to penetrate to the central or any other chambers. It still, therefore, remains a mystery if there is a blind tope, like many in India, or whether its secret still remains to reward some more fortunate set of explorers. If it has no central chamber, the curving inwards of its outer circle of stones is a curious instance of adherence to a sacred form.

The other monuments on the hill do not present any features worth enumerating in a general summary like the present, though they would be most interesting in a monograph. Though differing greatly in size and in richness of ornamentation, they all belong to one class, and apparently to one age. For our present purpose one of the most interesting peculiarities is that, like the group on the banks of the Boyne, this is essentially a cemetery. There are no circles, no alignments, no dolmens, no rude stone monuments, in fact. All are carefully built, and all more or less ornamented; and there is a gradation and progression throughout the whole series widely different in this respect from the simplicity and rudeness of the English monuments described in the last chapter.