Sea and River-side Rambles in Victoria/Chapter 11

RIVER SIDE RAMBLES.

__________

"Fairest sight in creation are these Rivers, whether small in their childhood, and found far among the mountains; or in rich manhood, sweeping through the open plains; or joining the Ocean at last in slow and exhausted old age—lovely are they at all times! And of the hymn of thanksgiving, which Nature sends forth from her many-toned voice, mounting up to her Creator's throne, the burden is borne by the Rivers."

CHAPTER XI.

THE MOORABOOL.

"Know ye not that lovely river?

Know ye not that smiling river?"

Early morning, or a summer's evening such as Keats describes as—

"Full loth this happy world to leave."

is the time for river-side wanderings, when we can divest ourselves of our cares and—

"Bare our foreheads to the cool blue sky,"

for it is at such times the whole world of Nature which retires during the fierce heat of mid-day comes forth in search of food and enjoyment. Let the true lover of Nature, intent on enquiring into her mysteries be stirring early; an hour after sunrise by the river's brink will give him matter for reflection the whole day long,—it is then the joyous matin song of the feathered tribes may be heard; then the innumerable families of insects issue forth from their many abiding places to fulfil their destined ends;—the finny tribes too intent on breakfast, as doubtless we shall be ere long,—rise greedily to prey on any stray bonne bouche, which has been wafted on the surface of their element, and the cattle return eagerly with that soft pleasant lowing, which sends our memories back to farm-yards of the old country, from the close stalls wherein they have been pent up for the night, to the grassy dew-sprinkled pastures which they love. How we long with them to wander "ankle deep in flowers" all the day through, casting off the feeling that there are such things as petty jealousies and rivalries every where surrounding us in our contact with mankind;—surely the communing with nature does much to soften down these feelings to which unhappily we are all more or less prone, and teaches us what mere specks we are in creation, and how much enjoyment might be had during our comparatively brief existence did we go the right way to work to find it. The lover of Nature becomes imbued with a kindly feeling to every living thing, and this surely must in a great measure be extended to his fellows.

There is a truth in the saying of old Isaac Walton, that the mere sitting by a river's side, is not only the quietest and fittest place for contemplation but will invite one to it. A Spanish writer too says, that "Rivers, and the inhabitants of the watery element, were made for wise men to contemplate, and fools to pass by without contemplation." Now, although we do not for one moment pretend that our Rivers rival those of Epirus, or Selarus, or the dancing waters of Elusuria, mentioned by our quaint piscator, or even those by which we have strolled at nightfall in the old country—the shrill scream of the Otter, the chorus of the Night-jar, the heavy splash of the Water-Rat, and the hoot of the Owl, the only sounds which disturbed the stillness, save and except the rising now and then of a splendid trout to our fly (for a lover have we been too of the gentle craft, and a paper of hackles even now recalls all the old scenes and excursions), still they have their own beauties, believe us, so we will be their champion. Have you ever visited the Moorabool? If not, then take advantage of the first fine day which offers itself, and away with you afoot to judge for yourself of the natural charms of this much maligned stream; we had heard it called slow, and sluggish, and paltry, but to it nevertheless we went, for we are not of those who are led away by popular prejudice, and there we beheld enough to clear it, in our eyes at least, from the slur cast upon it; truly—

"Hic gelidi fontes, hic mollia prata." — Virgil.

"Here are cooling springs, here grassy meads.

Let us walk now to the bridge at Fyansford, some two miles from Geelong; passing on our way the junction of the river which forms the subject of our paper, with the Barwon, just below the Falls:—here the banks remind us of the dark glen-like scenery of some parts of Ireland,—high hills, whose declivities reach to the water's edge, dark hollows intersecting, into which the daylight scarcely seems to glance, and for the various forms, animal and vegetable, which add to the charms of the picture—

"No breathing man

With a warm heart, and eye prepared to scan

Nature's dear beauty, could pass lightly by

Objects that look out so invitingly

On either side."

First now are the glittering Dragon flies, either fluttering over the plants which grow here, or striking us with amazement at their rapid hawk-like flight, and there is the black fan-tailed Fly-catcher, whose breast is pure white, and the remainder of its plumage jetty black, restlessly darting from one spot to the other, wagging its tail as it alights, and we cannot but pause to listen to the liquid notes of the Reed Warbler, hiding—

"And abiding

From the common gaze of men,

Where the silver streamlet crosses

O'er the smooth stones, green with mosses,

And glancing,

And dancing,

Goes singing on its way."

We walk awhile up the stream, and small as it is, the banks are indeed lovely to behold, planted as they are, despite the sad havoc made by cattle to which we may owe the barrenness of much of our river scenery, with rich dense masses of the fresh green Sea-rush, Scirpus maritimus, known to many by rivers near the sea at home, from the cover of which start a fine pair of Bitterns, who fly heavily and lazily away. Everywhere we are treading under foot the spicy Mints, the more fragrant the more they are crushed the delicate Convolvulus is twining elegantly round the stems of the Loosestrife, the pink flowers of which are always attractive, and the lovely white crimson petalled flowers of the Damasonium just peep above the surface of the water on which its dark green leaves float so refreshingly; our old friend, the Vervain, is here too, and the pretty pink Melaleuca paludosa. The crows' nests deposited on the few high trees which are left, show how the residences of the settlers on the margin of the river must have been despoiled of their palings and brushwood during the winter floods, which on some occasions have risen above the bridge at Fyansford. How merrily rushes the stream over its pebbly bed, musical as a young girl's laugh, anon, widening and becoming deeper, flowing quietly and gently, like the more mature thought of manhood. The very scum in some parts teems with animal life, skimming the surface of the water—

"——— Flumina libant

Summa leves."—Virgil.

and we carefully place portions of it in our bottles,—and in your leisure, beauties such as few of you have ever imagined, may be discovered therein; hair-like filaments of the most exquisite patterns conceivable,—long tubular cells containing beautiful green spiral coils, or numerous spherical granules or zoospores, moving restlessly about, and frequently striking against the walls of the cell, as if anxious to escape from confinement. This point gained after a while, they speedily begin to move hither and thither, now wheeling round and round, now oscillating from side to side, and now as if from sheer fatigue remaining quiescent. "Truly wonderful," says Hassell, in his "Freshwater Algæ," "is the velocity with which these microscopic objects progress, their relative speed far surpassing that of the fleetest race-horse. After a time, however, which frequently extends to some two or three hours, the motion becomes much retarded, and at length after faint struggles, entirely ceases, and the Zoospores then lie as though dead;—not so, nevertheless—they have merely lost the power of locomotion,—the vital principle is still active within them, and they are seen to expand, to become partitioned, and if the species be of an attached kind, each Zoospore will emit from its transparent extremity two or more radicles, whereby it becomes finally and for ever fixed. Strange transition from the roving life of the animal to the fixed existence of the plants." Of these Freshwater Algae, we may find here specimens of Conferva, Chara, Zygnema, Draparnaldia, Cladophora, Œdogonium, and many others, probably many species of each. Not useless are these minute plants either, affording as they do, food to so many tiny inhabitants of the water, and acting as purifiers to the water in which they dwell, decomposing and removing all that is noxious, and restoring to the water oxygen, which as we have previously stated, is essential to animal life.

In a former chapter we have recorded the Limnæa, Physa, and Planorbis as being abundant here, but on every one of the trees lying half in, half out of the water, are long dark shells (Unio), and from the way in which one end is invariably broken, they are evidently brought there by some creature which feeds on the dwellers within them, either the Bittern or the Water-Rat.

We have been fishing during our stroll, but it is sorry work, not a nibble scarcely but from a host of tittlebats or some such small fry, which at every cast of our bait have been raising our hopes to the highest pitch of expectancy;—we have changed it a dozen times, and our hooks as many more, but without success; still we can recommend our friends devoted to the sport to make a trial on the upper portions of this river, where Trout, Black Fish, and Eels may be taken and afford some sport. Well, if we cannot fill our creel there is nothing which so thoroughly refreshes us as a ramble away from the conventionalities of town life, where we can breathe freely, and we cannot but think with the agreeable author of "Life in the Woods," that one degenerates without frequent communion with Nature. "A single tree," says he, "standing alone, and waving all day long its green crown in the summer wind, is to me more full of meaning and instruction than the crowded mart or the gorgeously built town." Many is the happy hour we have whiled away here, half dreamy quiet thoughts stealing over us as the stream glided onwards, until the setting sun and—

"The flitting

Of divers moths, that aye their rest are quitting."

reminded us that we had many miles to go before reaching our destination. These were happy days indeed, on which we look back with pleasure not unmingled with sadness, for whose dreams are ever realised?

The higher up the "reedy stream" we go, the more beauties are unfolded to us; the Dog Rocks at Batesford of themselves will well repay the visitor, and the Geologist may load himself with fossils from them, and in every little indentation in the mud made by the footsteps of cattle by the river side, look well out for, (and bottle when found,) specimens of Desmidiæ and Diatomaceæ, which they generally contain. Were it not for the horror we in conjunction with others entertain of the Mosquito tribe, we would say have some in the Aquarium, for in their various stages they are interesting creatures,—in the larva state, having their heads always downwards, and their tails which are provided with a fan-like apparatus serving in some measure for respiration, on the surface of the water; whilst in the more advanced pupa stage the order of things is reversed, and the head takes the place of the tail, coming uppermost to the water's edge, and the respiratory organs are modified accordingly. Not a day passes in Summer, but we have unfortunately too frequent opportunities for witnessing the metamorphoses of these pests—in our ewers and our water barrels: to remedy the annoyance occasioned by their presence in the latter locality, a friend suggests a covering of very fine wire gauze, which if it would not prevent their development into the imago or perfect stage, would at any rate effectually put a stop to their roaming abroad, seeking whom they may devour. The roaring of the falls on the Barwon, just above where the two rivers meet, tempts us to stroll thither on our way homeward, and truly it is a sight which would gladden the heart of any real lover of the picturesque, the water dashing impetuously and musically down over the rugged rocks, lying in the river's bed, whilst on each side are cliffs, whereon one might botanise to his heart's content—

"Through meads and groves now calmly roves

The stream with many a bending;

In rippling song, through rushes long,

And pendent willows wending.

But groves at last and meads are passed,

And still with ceaseless motion,

The water glides, to pour its tides

Into the trackless ocean."

That feathery looking plant which covers yon bush, is a Clematis, belonging to the natural order, Ranunculaceæ or Crowfoot, and as much deserving the popular name of "old man's beard," as its twin sister of England and Ireland, where the field mice pull the feathered awns as soft linings for their nests. Of Violets, there is the large blue Betony-leaved (Viola betonicifolia) not certainly "stealing and giving odour," but playing the very mischief with us as it brings back to our mind's eye the groups of white and blue sweet-scented flowers well nigh hidden in their dense leafiness which tempted us to wander abroad in the fields and hedgerows of England, ere the chilliness of winter had disappeared. The green and scarlet native Fuschias may be gathered here, the Sida pulchella, Indigofera sylvatica, the cream-colored Stackhousia monogyna, with many of the Geraniaceæ. Turning aside to get a better and fuller view of the falls, which with the stream swollen by the late floods are grander and more impressive than usual, we observe the Ladies Bedstraw, Eurybiopsis, Cotula, so frequent by every wall and roadside, and of Goodeniaceæ, many species, which will be the better recognised, if the large leaved bushy one with ovate-dentate leaves and yellow flowers which is overhanging the stream, is first carefully examined, as it is one of the most conspicuous of the tribe. To embody here any idea of the many gems to be collected in this locality would be but tedious, but there are some rivalling the choicest plants of which our green-houses at home can boast, and all to the very tiniest, forming an important link in the Vegetable Kingdom; and as for Ferns,—not a dark or sheltered nook is without them. Well has Christopher North said, that "Nature does not spread in vain her flowers in flush and fragrance over every obscure nook of the earth,—simple and pure is the delight they inspire. Not to the Poet's eye alone is their language addressed. The beautiful symbols are understood by the lowliest minds."

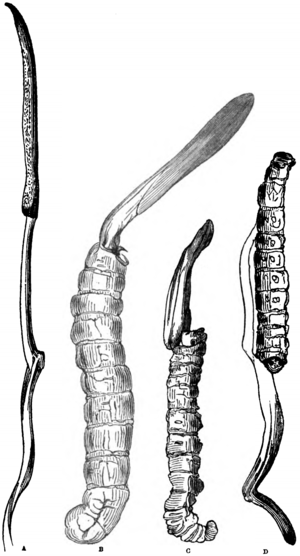

And although diverging somewhat from our path, the temptation of obtaining some good specimens of the Caterpillar Fungus tempts us up to Montpellier, and thence away to the Barrabool Hills where they abound;—this singular vegetable production springs from the neck of the dead larva of a moth, which, though when living, of a soft or fleshy character, when dead becomes perfectly hard and almost horny, so that it seems to form one substance with the parasite. This parasite is termed Sphceria, and species of it are dispersed through the Temperate Zones, growing generally upon decayed vegetable matter, and apparently immersed in the substance on which they are found, and so abundant that scarcely a decaying stick, leaf, or even grass stem, but presents some form or other of them; some too are met with on plants which are still living, but this may be looked upon as indicating a loss of vitality in the part of the plant so attacked. Hooker in his "Icones Plantarum" (Vol. 1, Tab. xi., published in 1837,) figures a New Zealand species (a), named after its discoverer, "Robertsii" and it is described as "black and cork like, the stipes or stem elongated, flexuose, simple or branched, the head acuminate, wormshaped." The native name of this plant is Areto or Hotito, and the residents in New Zealand call it the Bullrush Caterpillar, to which plant, more particularly in mature specimens in a state of fructification, it has some resemblance. The Caterpillar on the larva of which this grows is that of the Hepialus virescens, a moth belonging to the section Heterocera of Doubleday, and from its rapid flight known as the Swift Moth.

In 1857, a species differing in no way, so far as we can judge from dried species, from the former (although the larva is somewhat more attenuated than that figured by Hooker,) was discovered in Tasmania, and we are indebted to the kindness of W. K. Hawkes, Esq., of Franklin Village, Launceston, to whom the scientific world owes much of what is known on the Natural History of this interesting family, for a very well selected series of specimens, the plant arising in all, as in the former case, from the nape of the- neck, and in one individual also from the lateral spiracles, a circumstance to which our attention was called, prior to receiving any specimens so attacked, in a very obliging communication on the subject from Professor McCoy. The larva varies from two to three and a half inches, and the fungus from one to seven inches.

Another species (figure b), the S. Gunnii, was found in 1844, very abundantly at the back of Mr. Hawkes' garden in Tasmania,—it is totally unlike the former, the larva being of a lighter color, and varying from one to three and a half inches in length, and the fungus from one to eight inches, very black at the head, which is clavate; in some instances two stems arising from the same source. Of this species Mr. Hawkes writes:—"It is found generally under young Wattles or Gums, immediately after the first autumnal rains (about March). The Fungus with one to five stems, but generally with only one, usually shoots from the nape of the neck, in rare instances from other parts of the body, very seldom from the neck and tail. (In thousands of specimens four or five of these only have come before me.) The Chrysalis is found too with one stem from the upper part, and sometimes also encircled with rings of Fungus. The burrow made by the larva is about eighteen inches deep, the direction inclined; at the mouth the Larva and Chrysalis may be seen on the least alarm to retreat with precipitation. The perfect insect is a large grey moth coming forth in April or May."

Our specimens from the Barrabool Hills (c) appear to differ from S, Gunnii, only in being considerably smaller, as far as our own observations have extended,—in one individual the stipes rises as usual from the nape, whilst another from the same source creeps downwards to almost the whole length of the larva (d).

At the August meeting (1854) of the Royal Society of Tasmania, a communication was read from Mr. H. Hull, on a paragraph in the writings of Christian Franc Paulinus, in the 9th century, which states that certain trees in the island of Sombrero (e 1) have large worms attached under ground in place of roots, and Mr. Hull considered this as an indication of the knowledge at that early period of some species of plant Caterpillar; any way one species S. sinensis (Berkeley) found in Thibet, has been described in our Pharmacopeias. It is figured in Lindley's " Vegetable Kingdom," the stipes being made up in bundles for the market. Redgood remarks of it, that it is developed on the neck of a Caterpillar, (probably an Agrotis,) and is considered to possess strengthening and renovating properties, but owing to its rarity is only employed in the Emperor's palace after this fashion:—a duck is stuffed with five drachms of the Fungus and roasted slowly, and after the flesh is thoroughly impregnated, it is to be eaten daily for eight or ten days.

The doubt arises in our mind, whether the larva is attacked when living and eventually killed by the germination of the plant, or does its dead body afford that peculiar stage of decomposition favorable to the growth of the Fungus? In support of the former opinion, we know of one species of Fungus, the Botrytis Bassiana causing the disease called muscardine, and resulting, as C. R. Bree, Esq., in a paper on the "Diseases of Silkworms," (Naturalist, 1858, p. 215,) explains, from an excess of acidity attacking the worm before its entrance into the chrysalis state, and in the West Indies it is not at all uncommon to see a description of Podistes flying about with plants of a fungoid nature streaming from its body, the germs as Carpenter ("The Microscope," page 379,) suggests, having been probably introduced through the breathing pores at their sides and taken root in their substance, so as to produce a luxuriant vegetation. A specimen of this wasp with a Sphæria attached, from Jamaica, was exhibited at the Botanical Society of Edinburgh, in August, 1858. Nor is the human frame exempt from such growths, for Sarcina ventriculi is the cause of some painful forms of dyspepsia, and Dr. Carpenter speaks of the probability of its inhabiting the stomach in large quantities, and for a considerable time without causing inconvenience; and in animal tissues the Fungi are produced more especially in certain diseased conditions of the epidermal system, or of the mucous membranes, and their presence in such cases seems to cause an alteration in the phenomena of disease. (Balfour's "Class Book of Botany," Vol.1, p. 346.)

Dr. Hooker, whilst in the "Erebus," collected specimens, and all the information he was able, but still confesses himself at a loss to account for its development. Mr. Taylor and Mr. Colenso, he adds, being of opinion that in the act of working into the soil to undergo their metamorphosis, the Caterpillars get the Fungus spores lodged in the first joint of the neck, and finally settle head uppermost. So far, the opinion of our friend, (Mr. Hawkes) is corroborative, but he further adds, that "having gained access to the interior of the body, the spores germinate at the expense of the fat which lies beneath the skin of the animal, growing rapidly on the material that ought to feed the grub, and at last killing it by exhaustion. The growth of the plant proceeds,—all the soft parts of the grub are progressively consumed or appropriated by the plant, which, after thus distending the integument of its prey, bursts forth at the weakest point, usually that piece of fine skin which connects the head and body of the grub; the plant, now requiring light, shoots out of the earth, develops its spores which are dispersed in the air and fall to the soil, prepared to take advantage of any similar nidus into which they may be accidentally introduced."

Even with these opinions before us, we are disinclined to believe that any insects in a healthy state can afford those conditions which are essential to the development of fungoid growths, for as is remarked in Art. "Enterophyta." Nat. Hist. Sect. Engl. Cyclo., "a failure of the ordinary vital powers to carry on the healthy processes of life seem ordinarily to be the inviting cause of such a development of these plants as would constitute a disease," but we conceive that it is only after life is destroyed and decomposition set in that the Sphæria commences to germinate,—our friends however must observe and judge for themselves.

But our ramble has occupied more time than we anticipated, so we will only descend the hill towards the Barwon on our way homewards, gathering as we go some specimens of the remarkable Polygonum junceum or the Crantzia Australasica growing submersed in the water.