Sister Eloise

Sister Eloise

BY EDITH BALLINGER PRICE

Illustrations by the author

THE gray-walled convent garden lay hushed and warm in the sunlight of noon. Its gentle silence was scarcely shaken by the thunder of the guns, which had now become, within those sun-flecked walls, as accustomed a sound as the tiny booming of the bees among the flowers. The cedar that stood at the corner of the wall, stretching out dark, adventurous boughs into the outer world, cast moving splashes of shadow on the grass. From a yellow rose beside the paved path three petals fell, hovered momentarily down the still air, and touched the worn stones like three kisses.

But the dreaming garden became suddenly a place of small laughter, of little cries and excited chattering. From the shadow of the cloister arches into the gilding sunshine came scampering hand in hand a troop of little children, very happy that it was time for the recess. They were children of the village of Nichy, four miles to the northward, and since that thundering of the guns had been so ominously steady, they had lived in the convent, studying their lessons with the sisters and playing in the high-walled garden. Somewhere their fathers fought for France, and there in Nichy their mothers clung fiercely to the cottages that might at any moment be taken from them. Some of those good fathers were already huddled into forgotten graves or stretched under the sky in no-man's-land, but the children still laughed in the garden of Sainte Scholastique, confident that papa would very soon return en permission, with presents bulging from his pockets, and a Boche helmet to clap on a proud little head.

Behind the children, with her hands folded under her wide sleeves, walked Sister Eloise, the heavy rosary at her girdle swinging rhythmically with a faint click. Sister Eloise was no longer young, nor had she ever been beautiful. Her round, steel-rimmed spectacles had made an ineradicable line upon the bridge of her nose, and from behind them her wide hazel eyes peered out with a gently surprised air. She had entered the convent at the age of nineteen, because her firm convictions and a true religious devotion would let her do nothing else, but also partly because she had thought herself too plain and too timid to make her way in the more difficult world. Now, after thirty years, she would certainly have believed this to be quite as true, if she had ever thought of it at all since then. Plainer than before, she would undoubtedly have said, and more timid also; and she would have dismissed the matter from her mind in haste, with none of the heart-burning of her youth. But Sister Eloise had not entertained such thoughts for many years, and as she followed the children into the sunshine, her eyes, dazzled for a moment by the sudden splash of light, expressed only a faintly anxious solicitude.

The children, after a gleeful scamper about the garden, came by twos and threes to stand at her knee, where she sat on a bench by the cedar-tree; for they all loved her dearly. She it was who invented games for them in the recess, and gave them more porridge when the mother superior was not looking, and came to kiss each occupant of the row of little beds after Sister Denise had carried away the lights. She never gave them hard lessons to do, like Sister Félicité, or kept them alone in the school-room because they could not spell difficult words like fenêtre and escalier. (Were not Antoine and Jean-Marie kept in at this very moment for that very same reason?) Indeed, she never gave them any lessons at all, for it was the duty of Sister Félicité and three others to teach the little school. They stood much in awe of the mother superior, for she was very tall, and she had a large nose, and eyes that looked into one's inside heart if one had been naughty. When they were naughty she struck their hands twice with a long ebony ruler, but she patted their heads afterward. And Sister Eloise was always waiting behind the door to kiss them and wipe their eyes,and give them a very small confiture, which she produced mysteriously from her large pocket.

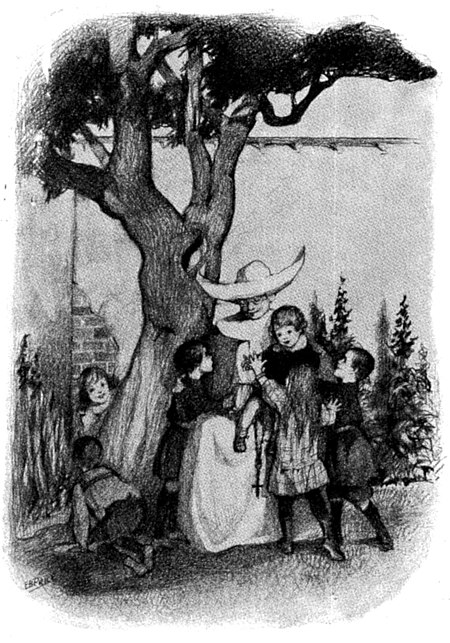

Now, in the garden, the children clustered about her, all talking at once.

"My papa sent me to-day a carte-postale!" cried Virginie above the others. "Look, Sister Eloise! How splendid he looks in his uniform, how beautiful he looks!"

"My papa looks more splendid than the papa of Virginie," shouted Gustave. "He is a sergeant, he is."

"My papa sent me yesterday a bracelet made from an obus," cried Jeanne, thrusting a rather thin little arm, adorned with the trophy, before Sister Eloise.

"Oh, how charming, how enchanting!" said the sister. "But, no; the papas are both good and splendid soldiers, fighting for our dear France. Do not climb into the tree, Martin; it might be that it would break," she added, trying to admire, answer, and admonish in one breath.

Michel came and put his hand on her knee. His gray eyes were faintly apprehensive.

"Listen," he said. "Is it not that the guns are nearer to-day? Are they not every day nearer?"

The children listened, silent. To the north the constant booming was now sometimes broken by a sharper sound, a crackling crash. Sister Eloise laughed a little.

"It is so still to-day, so hot," she said, "the sound comes very clearly to us. It is many, many miles away. Run, mes petits; run and play, and make yourselves hungry for the luncheon."

They ran, laughing, but Michel sat under the cedar-tree with his chin in his hands, and he was trembling a little. His father had been killed the week before.

Sister Eloise was about to gather her little band together to march them two and two into the convent. She arose, and called to them, shading her eyes and beckoning. She was facing the blinding glare of the sun on the wall and could not see, but she heard overhead a sudden noise, and saw something hovering; then the sky rushed down on her with an annihilating crash, and the world was swirling black, torn with fire and slashed with screams.

A flying sliver of stone had gashed Sister Eloise's forehead. She sat up, wiped the blood from behind her spectacles with her apron, and then stood up dizzily. The children were huddled in the corner of the wall under the cedar, with white faces turned toward her, and horror-stricken eyes looking beyond her. She turned to follow their fixed gaze, and saw.

The Convent of Sainte Scholastique had been stoutly built, but it was also very ancient, and its destruction had not been a difficult matter. Some of its old buttresses still stood erect, with fragments of arched windows clinging between the shattered piles. More than half of the roof had fallen in, and a great, unrecognizable mass of shivered stone and splintered beams marked the refectory and the main hall. Part of the cloisters, with the little stairway to the chapel, was standing bravely, but the chapel door lay prone, torn from its hinges. A whitish dust was settling slowly throughout the ruin.

Sister Eloise turned to the stricken group under the cedar. The third time she tried to speak she was successful.

"You are all here? All?" she asked, and counted on her fingers, looking from one white face to another, "Gustave, Michel—where is Antoine—and Jean-Marie?" she cried suddenly. Michel ran to her, pointing.

"They were there," he said scarcely audibly. "They had tasks to do. Sister Félicité gave them tasks till luncheon. They were in the school-room."

Sister Eloise gently detached her hand from Michel's.

"Stay quietly, children," she said; "I will return quickly to you."

They surged toward her with little moans, and she putout her hands to stay them.

"Nothing will hurt you now. Sit quietly on the grass.I will return quickly."

She left them, the great skirt of her gown rustling softly across the paved path. At the little stairway which led to the chapel she turned around and waved her hand to them. They saw her wipe her forehead with her apron, and then she crept over the fallen door on her hands and knees and disappeared.

Part of the roof of the chapel had fallen in, and part of the wall. The golden candlesticks of the altar were lying twisted in the debris on the floor. Sister Eloise, standing upright again, instinctively blessed herself before the painted statue of the Virgin. It had fallen half forward, and was caught against a pillar, unbroken, In this leaning position, the eyes of the Child in the Virgin's arms seemed gazing toward a spot on the pavement behind a fallen choir-stall; His uplifted hand seemed to bless something there. In that place lay the mother superior. Her eyes were open, and her thin hands were clasped tightly over her crucifix. Sister Eloise picked up two of the battered candlesticks and set them at her head among the wreckage. She bent, closed the mother superior's eyes, and went on.

The door into the passage that led out of the chapel was blocked to half its height. Sister Eloise brought a bench and climbed over. She felt her way down the passage and into the entrance hall, where the roof was gone and there was light. As she went she called the names of the other nuns, but there was no answer, no sound but now and then the crack of small pieces of stone and mortar falling somewhere throughout the ruin.

"NOW, IN THE GARDEN, THE CHILDREN CLUSTERED ABOUT HER"

"If I can only reach the school-room!" gasped Sister Eloise as she struggled through the hall, and then, as a sudden thought came to her, "Sainte Vierge! all the others,—the mother was at prayer,—but the others were without doubt in the refectory. It is the very hour of the luncheon." She had seen the shattered heap of stone that was the refectory.

"But Antoine and Jean-Marie, perhaps they had not quite yet been called from their tasks."

She went on. When she reached the door of the school-room she found it wedged between two fallen beams and buttressed with heaped bricks. Sister Eloise pushed back her wide sleeves, and raised in her arms a long piece of timber. She swung it back and battered the door with it, but the door did not give way.

"Seigneur, aidez-moi!" she prayed in little gasps as she battered.

At length the beam on the other side,which had not been firmly wedged, was jarred away and slipped off. The door fell in with a crash, and the light poured through the rising mortar-dust. Sister Eloise entered the school-room.

Between the overturned desks papers fluttered among the bricks and debris, and pools of ink spread and trickled darkly across the cracked pavement. The globe of the world was upset, with its legs pointing grotesquely upward, and the large map of France hung down in two strips from the wall behind Sister Félicité's desk.

Antoine lay on his face near the door. Beside him was his slate, and as Sister Eloise stooped down, she read on the unbroken part: "3 + 8 = 12. Trois et huit font douze," very carefully written, and underneath, in a sudden scrawl, "Vive la France!" Sister Eloise saw that she could do nothing for Antoine. As she stood up she saw Jean-Marie. The stone lintel of the window had fallen upon him,and lay across his legs. Sister Eloise put her hands under it and raised it up an inch.

Jean-Marie was six years old. He it was to whom Sister Eloise was wont to give two confitures when the mother superior punished him, which was often; he for whom she saved the largest tartine when Sister Félicité kept him in to finish his lesson, which was oftener; he whom she kissed most of all when Sister Denise had left the dormitory.

She dragged at the stone till she had raised it six inches, and propped it there with a brick. When she had lifted Jean-Marie she wrapped him in the corner of her great gray cloak, through which a dark spot spread slowly. She turned and climbed over the littered threshold.

It had been almost an hour since she had left the children in the garden. They were sitting silently, with their faces turned toward the chapel door.

"Where is Antoine?" asked Michel.

"Antoine has gone away. He is not hurt," said Sister Eloise. "Come, mes chéris; we will go away from here."

She gathered Jean-Marie in one arm,and took Georges by the hand. He was the littlest one.

"I am hungry," said a little girl.

Sister Eloise led the way through the garden-door into the road, and turned toward Nichy.

"We will eat presently," she said. "Here there is nothing to eat."

The way was along a straight road bordered on each side by a line of trees, and when they had walked for perhaps more than a mile, many of these trees were broken off short, and some of them lay across the road, with their great tangled branches withering in the dust. Sister Eloise helped the children over.

"It is not much farther to walk," she said. "Soon you will see your dear mothers, and we will eat. Is this not amusing, climbing over the trees? Let us pretend that it is a great river that we are crossing by means of logs and rafts.Hurry, Virginie! vite! The torrent will catch you."

Virginie scrambled over with a will, and they trudged on.

At the end of the third mile Jean-Marie opened his eyes.

"Why are you carrying me, Sister Eloise?" he asked. "I am too heavy. I will walk."

"Mais non," she said gently; "you are not heavy." As she looked down at him he tried to cling to her.

"Something hurts," he whispered, and lost consciousness again.

As Nichy became visible on the hill-top, Sister Eloise wondered a little at the brightness of the sunset behind it. Then almost immediately she thought:

"But no, how can it be? Nichy is in the north; it is the north we are facing. The sun sets behind the wood of Saint Monique."

When they had walked for a few moments longer, she saw that Nichy was in flames, and that against the sky-line were black cages that had been houses, and from them burst long waves of fire leaping into the sky. High overhead a shell droned through the air. Some of the children whimpered a little, and clustered around Sister Eloise*s skirt.

"We must hurry," she said, "and we must be quiet. Do not be afraid."

She led the way back along the obstructed road. Presently she turned with certainty into a little lane that wound across the fields and through a wood in which many of the trees were splintered and fallen.

"I am too tired," sobbed Virginie.

"And I."

"I, too," cried several faint little voices.

"We will rest here for a little while," said Sister Eloise, looking about her and listening. "Lie on the grass, my children; do not be afraid. Hear the thrush singing so beautifully."

Indeed, there was a thrush singing, and a star had come out, and was hanging like a paler spark over Nichy.

Sister Eloise sat down upon the grass, holding Jean-Marie in her arms. Georges went to sleep with his head on a corner of her skirt.

When they were a little rested, they went on again, and all at once came to a dark farm-house. The windows were all broken, and there was a great hole in the roof; but three walls were standing firmly, and all was silent and deserted.

"Now we have arrived!" cried Sister Eloise, cheerfully. "Wait here a moment, and I will fetch a candle."

A disordered bed stood near the door,and on it she laid Jean-Marie. Then she peered about through the rooms until she found an overturned candlestick with two or three fusees beside it, where they had all fallen from a shelf.

She came to the door, shading the candle with her hand, and the orange light flickered up across her spectacles and her great white coif. The children trooped in stiffly, and Sister Eloise set the candle on the mantel-ledge, from other rooms brought mattresses and blankets, and spread them on the floor, enough for each child to have a bit to lie on.

"You promised that we should eat soon," said Jeanne.

"You shall eat now," said Sister Eloise.

From the store-room she brought a ham, and gave them each a small slice of it, smoked and dry. It was only a small slice, for there was not much food in the store-room.

"Something to drink, too," said Michel, for the ham was very salt.

Sister Eloise went in search of the well, and found it at length, buried beneath the fallen wall of the house, with immovable heaps of wreckage encompassing and filling it.

"There is no water here," she said when she had gone back to the children, "but I will bring some. Do not be afraid if I leave you. There is nothing to fear."

"But if you did not return!" cried several voices in agony. "Do not go away! Do not leave us!"

"I will return to you. Try to sleep, and do not fear."

She hesitated for a moment, and then, smiling, took from her large pocket some little confitures, and gave one to each child. Then, taking up two wooden pails, she blew out the candle.

The next farm was almost two miles away across the fields, but the well was unharmed, and the water was sweet and pure. The farm-house was deserted, but it had not been destroyed.

"SHE TURNED AND CLIMBED OVER THE LITTERED THRESHOLD."

"It would perhaps be a better place for them here, if we could come to-morrow," thought Sister Eloise. "I could bring the food little by little if there is none here."

As she was considering how best to manage it, she heard clearly in the night air the sounds of guttural voices not a hundred yards away, and then a terrific crash and recoil. A big enemy gun was concealed in the little copse behind the farm-house, and was finding its range for the new French position. Sister Eloise, skirting the wall cautiously with her full buckets, gained the shelter of a tall clump of bushes, from which the ground sloped down sharply, concealing her well enough for the next stage of her journey, till she should be completely covered by the dark-ness and distance. It was a journey, she now saw plainly, to be taken at night only, and then with great care. That the children must have water was apparent, and that there was no other place in which to get it for many a stricken mile she knew very well, so that she trudged back across the fields with no doubt at all as to what must be done. It was possible that with another change of the French line the big gun might be removed; but in any case water must be brought, from under its muzzle, if necessary.

Some of the children were awake when she returned, but most of them were asleep, worn out with their weary tramping. To the wakeful ones she gave a little water to drink, after lighting again the candle on the mantel-shelf. Then she went to Jean-Marie. He was wholly conscious, and held the skirt of her gown very tightly while she washed his wounds, and bound them with strips torn from one of her great linen petticoats. She sat beside him then, holding his hand in the darkness, and patting it when he whispered:

"Why do I hurt, Sister Eloise?"

It was very still, because the heavy firing had ceased, and small night noises could be heard. Jean-Marie's hand clung very close, and the dawn was long in coming.

One day was much like another in the broken farm-house. At first Sister Eloise dared to let the children run about in the sunshine outside the door, but there came a time when that could not be. Enemy aircraft drifted overhead too constantly, and the guns were battering their way ever nearer. Nichy was taken and re-taken, though of that Sister Eloise knew nothing. She knew only that shells came pounding now and then into the field before the farm-house, tearing great wounds in the earth, and splintering the trees in the orchard. She moved her little flock into the cellar, letting them out for a little while every evening after dusk, when there was no danger of their being seen by an airplane. In the cellar there was no light either by night or day, for they had no more candles. The mattresses and blankets were put down there, and some hay also, which she had found in a shed. With a blanket over it, the hay was softer than a mattress. She also brought down there what food remained.

The children complained at nothing. They sat quiet, gazing with a sort of indifference at the shafts of dusty light which penetrated the cellar. They had accepted everything, since the moment when they had huddled together there in the convent garden, in the same bewildered silence. They feared only that Sister Eloise might leave them, and sometimes followed her as she moved about the cellar, plucking at her gown. Their eyes, dilated in the constant twilight of the place, wore a piteous, haunted look.

Every night when the children slept, Sister Eloise went across the fields for the water. The German gun was still in the little wood, and she was very cautious in her approach to the well. One night, as she peered from behind the angle of the wall which made her last shelter before creeping fifty feet in the open, she saw the glint of helmets at the well, where three German soldiers were drinking, and she lay motionless for an hour, while the men talked and smoked, before they walked slowly back into the wood.

Every night she went, creeping behind the same bushes as she neared the farm, running the same open places, crouching behind the wall, noiselessly drawing the water, and then back to the other farm-house, where it loomed, a hardly palpable shadow in the night, with square patches of sky seen faintly paler between its yawning rafters. At the entrance to the cellar she always paused, listening. Through the utter dark she could feel their breathing. Sometimes, despite herself, a wild thought seized her heart.

"If some one had come while I was away, if the children had been taken out, if it were German soldiers that breathed there in the darkness!"

And then from the silence would come a little inarticulate sound of fright, and she would be there instantly, holding to her a trembling little child, half awake and already comforted.

To Jean-Marie, whose cry it most often was, she came as the only thing of comfort and security in a world of darkness and terror. For him the pain had become one with the dark and the roar of the guns, nothing even as conscious as a nightmare, but merely a whole hideous fabric of unbelievable existence. He understood nothing which had happened, and nothing was real to him, not certainly the children,whose faces he could scarcely see as dim, white ovals in the darkness, whose low voices he heard about him. Sister Eloise was the only reality. He heard the swirl of her gown and saw a glint of light on her spectacles as she bent over him, and her arms, as she lifted him, were warm and real and very comforting. He did not understand why she washed and bound his legs every day, or connect it with his increased suffering at the time; but he understood her words: "Mon brave! Mon chéri! Ah, Jean-Marie!"

Michel followed Sister Eloise always.

"If my papa were not killed, he would take us out He would come and take us out," he said over and over. "Why do not the other papas who are not killed come for us?"

"They are trying to," Sister Eloise would say. "They are fighting for us now that we may come out."

But they stayed on in the cellar.

The moon had risen fair and full over the little wood and stood above it, making all the meadows about silver-gray and bright. The trees and the edges of shell-holes threw sharp, dark shadows, and of these Sister Eloise availed herself as she crept forward with her buckets. Lying prone at last behind the wall, and praying that the moon might quickly be veiled by a cloud, she caught again the gleam of helmets and heard low voices at the well. Then all at once she saw that they were not German, but the steel trench-helmets of France. As she sank back, hardly daring yet to believe, and waiting to look again that she might be sure, one of the buckets fell over, thudding against a stone and rolling for a few feet, with its bail clattering. There was the click of a rifle being cocked, and a quick voice cried out:

"Qui Vive?"

"Sainte Vierge, can it be true?" she whispered. "C'est moi, only I," gasped Sister Eloise as she stepped into the moonlight.

"IN THE DOORWAY STOOD SISTER ELOISE"

Within the farm-house a colonel of artillery and two captains were bending over a litter of papers on a table. Two or three lieutenants sprawled and smoked in a corner. A candle stuck in a bottle burned gustily on the table, dribbling tallow on the documents below it. The officers straightened their tired backs and looked around quickly as the shaky door was banged open by the guard and a flood of moonlight streamed in. In the doorway stood Sister Eloise, her stained gray cloak drawn around her, and her rumpled white coif shimmering in the pale light. From behind her large spectacles her eyes, somewhat bewildered, rather anxious, and very much relieved, gazed at the colonel, who cried:

"Diable!"

Then he jumped up suddenly, pulling off his cap.

"Where can you have come from, Sister? This is n't a healthy place," he said.

Sister Eloise told him in a very few words what had brought her there.

"The water must be had, Monsieur le Colonel," she explained. "They must all drink, and one little one is badly hurt. It is necessary to wash very often his wounds, you understand, for he has had no proper medical care."

"And how long do you say that you have been living in this hole with these children?" asked the colonel

"I do not know, Monsieur le Colonel," said Sister Eloise, frowning a little and considering. "Perhaps something more than six weeks. Perhaps as long as two months. I cannot be sure."

She glanced suddenly around the room, and took a step toward the door.

"You must excuse me, Monsieur," she said. "If I may now draw the water, I must return to my children."

I saw Sister Eloise not long ago in a big hospital near Paris. She put down the tray she was carrying and came forward, smiling, when she heard of the jeune Americaine who was eager to meet her. She took my hand and held it in hers, while her eyes shone with pleasure behind her large spectacles.

"How brave you are, chère miss!" she said, "to come across the sea when the submarines of the enemy are so dangerous. I admire greatly the grande courage of all the American young ladies, vous autres, who so bravely come to help our dear France. Me, I am timid; I have lived always in the convents, you understand; I have not the courageous heart"

I could say nothing. My stammered words seemed more than senseless. She held my hand a moment, and then, catching up her tray, hurried off down the corridor, her great skirts rustling, and the rosary at her girdle clicking faintly.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1930.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1997, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 27 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse