South: the story of Shackleton's last expedition, 1914-1917/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V

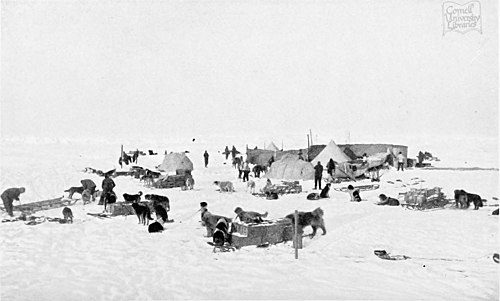

OCEAN CAMP

In spite of the wet, deep snow and the halts occasioned by thus having to cut our road through the pressure-ridges, we managed to march the best part of a mile towards our goal, though the relays and the deviations again made the actual distance travelled nearer six miles. As I could see that the men were all exhausted I gave the order to pitch the tents under the lee of the two boats, which afforded some slight protection from the wet snow now threatening to cover everything. While so engaged one of the sailors discovered a small pool of water, caused by the snow having thawed on a sail which was lying in one of the boats. There was not much—just a sip each; but, as one man wrote in his diary, "One has seen and tasted cleaner, but seldom more opportunely found water."

Next day broke cold and still with the same wet snow, and in the clearing light I could see that with the present loose surface, and considering how little result we had to show for all our strenuous efforts of the past four days, it would be impossible to proceed for any great distance. Taking into account also the possibility of leads opening close to us, and so of our being able to row north-west to where we might find land, I decided to find a more solid floe and there camp until conditions were more favourable for us to make a second attempt to escape from our icy prison. To this end we moved our tents and all our gear to a thick, heavy old floe about one and a half miles from the wreck and there made our camp. We called this "Ocean Camp." It was with the utmost difficulty that we shifted our two boats. The surface was terrible—like nothing that any of us had ever seen around us before. We were sinking at times up to our hips, and everywhere the snow was two feet deep.

I decided to conserve our valuable sledging rations, which would be so necessary for the inevitable boat journey, as much as possible, and to subsist almost entirely on seals and penguins.

A party was sent back to Dump Camp, near the ship, to collect as much clothing, tobacco, etc., as they could find. The heavy snow which had fallen in the last few days, combined with the thawing and consequent sinking of the surface, resulted in the total disappearance of a good many of the things left behind at this dump. The remainder of the men made themselves as comfortable as possible under the circumstances at Ocean Camp. This floating lump of ice, about a mile square at first but later splitting into smaller and smaller fragments, was to be our home for nearly two months. During these two months we made frequent visits to the vicinity of the ship and retrieved much valuable clothing and food and some few articles of personal value which in our light-hearted optimism we had thought to leave miles behind us on our dash across the moving ice to safety.

The collection of food was now the all-important consideration. As we were to subsist almost entirely on seals and penguins, which were to provide fuel as well as food, some form of blubber-stove was a necessity. This was eventually very ingeniously contrived from the ship's steel ash-shoot, as our first attempt with a large iron oil-drum did not prove eminently successful. We could only cook seal or penguin hooshes or stews on this stove, and so uncertain was its action that the food was either burnt or only partially cooked; and, hungry though we were, half-raw seal meat was not very appetizing. On one occasion a wonderful stew made from seal meat, with two or three tins of Irish stew that had been salved from the ship, fell into the fire through the bottom of the oil-drum that we used as a saucepan becoming burnt out on account of the sudden intense heat of the fire below. We lunched that day on one biscuit and a quarter of a tin of bully-beef each, frozen hard.

This new stove, which was to last us during our stay at Ocean Camp, was a great success. Two large holes were punched, with much labour and few tools, opposite one another at the wider or top end of the shoot. Into one of these an oil-drum was fixed, to be used as the fireplace, the other hole serving to hold our saucepan. Alongside this another hole was punched to enable two saucepans to be boiled at a time; and farther along still a chimney made from biscuit-tins completed a very efficient, if not a very elegant, stove. Later on the cook found that he could bake a sort of flat bannock or scone on this stove, but he was seriously hampered for want of yeast or baking-powder.

An attempt was next made to erect some sort of a galley to protect the cook against the inclemencies of the weather. The party which I had sent back under Wild to the ship returned with, amongst other things, the wheel-house practically complete. This, with the addition of some sails and tarpaulins stretched on spars, made a very comfortable storehouse and galley. Pieces of planking from the deck were lashed across some spars stuck upright into the snow, and this, with the ship's binnacle, formed an excellent look-out from which to look for seals and penguins. On this platform, too, a mast was erected from which flew the King's flag and the Royal Clyde Yacht Club burgee.

I made a strict inventory of all the food in our possession, weights being roughly determined with a simple balance made from a piece of wood and some string, the counter-weight being a 60-lb. box of provisions.

The dog teams went off to the wreck early each morning under Wild, and the men made every effort to rescue as much as possible from the ship. This was an extremely difficult task as the whole of the deck forward was under a foot of water on the port side, and nearly three feet on the starboard side. However, they managed to collect large quantities of wood and ropes and some few cases of provisions. Although the galley was under water, Bakewell managed to secure three or four saucepans, which later proved invaluable acquisitions. Quite a number of boxes of flour, etc., had been stowed in a cabin in the hold, and these we had been unable to get out before we left the ship. Having, therefore, determined as nearly as possible that portion of the deck immediately above these cases, we proceeded to cut a hole with large ice-chisels through the 3-in. planking of which it was formed. As the ship at this spot was under 5 ft. of water and ice, it was not an easy job. However, we succeeded in making the hole sufficiently large to allow of some few cases to come floating up. These were greeted with great satisfaction, and later on, as we warmed to our work, other cases, whose upward progress was assisted with a boat-hook, were greeted with either cheers or groans according to whether they contained farinaceous food or merely luxuries such as jellies. For each man by now had a good idea of the calorific value and nutritive and sustaining qualities of the various foods. It had a personal interest for us all. In this way we added to our scanty stock between two and three tons of provisions, about half of which was farinaceous food, such as flour and peas, of which we were so short. This sounds a great deal, but at one pound per day it would only last twenty-eight men for three months. Previous to this I had reduced the food allowance to nine and a half ounces per man per day. Now, however, it could be increased, and "this afternoon, for the first time for ten days, we knew what it was to be really satisfied."

I had the sledges packed in readiness with the special sledging rations in case of a sudden move, and with the other food, allowing also for prospective seals and penguins, I calculated a dietary to give the utmost possible variety and yet to use our precious stock of flour in the most economical manner. All seals and penguins that appeared anywhere within the vicinity of the camp were killed to provide food and fuel. The dog-pemmican we also added to our own larder, feeding the dogs on the seals which we caught, after removing such portions as were necessary for our own needs. We were rather short of crockery, but small pieces of venesta-wood served admirably as plates for seal steaks; stews and liquids of all sorts were served in the aluminium sledging-mugs, of which each man had one. Later on, jelly-tins and biscuit-tin lids were pressed into service.

Monotony in the meals, even considering the circumstances in which we found ourselves, was what I was striving to avoid, so our little stock of luxuries, such as fish-paste, tinned herrings, etc., was carefully husbanded and so distributed as to last as long as possible. My efforts were not in vain, as one man states in his diary: "It must be admitted that we are feeding very well indeed, considering our position. Each meal consists of one course and a beverage. The dried vegetables, if any, all go into the same pot as the meat, and every dish is a sort of hash or stew, be it ham or seal meat or half and half. The fact that we only have two pots available places restrictions upon the number of things that can be cooked at one time, but in spite of the limitation of facilities, we always seem to manage to get just enough. The milk-powder and sugar are necessarily boiled with the tea or cocoa.

"We are, of course, very short of the farinaceous element in our diet, and consequently have a mild craving for more of it. Bread is out of the question, and as we are husbanding the remaining cases of our biscuits for our prospective boat journey, we are eking out the supply of flour by making bannocks, of which we have from three to four each day. These bannocks are made from flour, fat, water, salt, and a little baking-powder, the dough being rolled out into flat rounds and baked in about ten minutes on a hot sheet of iron over the fire. Each bannock weighs about one and a half to two ounces, and we are indeed lucky to be able to produce them."

A few boxes of army biscuits soaked with sea-water were distributed at one meal. They were in such a state that they would not have been looked at a second time under ordinary circumstances, but to us on a floating lump of ice, over three hundred miles from land, and that quite hypothetical, and with the unplumbed sea beneath us, they were luxuries indeed. Wild's tent made a pudding of theirs with some dripping.

Although keeping in mind the necessity for strict economy with our scanty store of food, I knew how important it was to keep the men cheerful, and that the depression occasioned by our surroundings and our precarious position could to some extent be alleviated by increasing the rations, at least until we were more accustomed to our new mode of life. That this was successful is shown in their diaries. "Day by day goes by much the same as one another. We work; we talk; we eat. Ah, how we eat! No longer on short rations, we are a trifle more exacting than we were when we first commenced our 'simple life,' but by comparison with home standards we are positive barbarians, and our gastronomic rapacity knows no bounds.

"All is eaten that comes to each tent, and everything is most carefully and accurately divided into as many equal portions as there are men in the tent. One member then closes his eyes or turns his head away and calls out the names at random, as the cook for the day points to each portion, saying at the same time, 'Whose?'

"Partiality, however unintentional it may be, is thus entirely obviated and every one feels satisfied that all is fair, even though one may look a little enviously at the next man's helping, which differs in some especially appreciated detail from one's own. We break the Tenth Commandment energetically, but as we are all in the same boat in this respect, no one says a word. We understand each other's feelings quite sympathetically.

"It is just like school-days over again, and very jolly it is too, for the time being!"

Later on, as the prospect of wintering in the pack became more apparent, the rations had to be considerably reduced. By that time, however, everybody had become more accustomed to the idea and took it quite as a matter of course.

Our meals now consisted in the main of a fairly generous helping of seal or penguin, either boiled or fried. As one man wrote:

"We are now having enough to eat, but not by any means too much; and every one is always hungry enough to eat every scrap he can get. Meals are invariably taken very seriously, and little talking is done till the hoosh is finished."

Our tents made somewhat cramped quarters, especially during meal-times.

"Living in a tent without any furniture requires a little getting used to. For our meals we have to sit on the floor, and it is surprising how awkward it is to eat in such a position; it is better by far to kneel and sit back on one's heels, as do the Japanese." Each man took it in turn to be the tent "cook" for one day, and one writes:

"The word 'cook' is at present rather a misnomer, for whilst we have a permanent galley no cooking need be done in the tent.

"Really, all that the tent-cook has to do is to take his two hoosh-pots over to the galley and convey the hoosh and the beverage to the tent, clearing up after each meal and washing up the two pots and the mugs. There are no spoons, etc., to wash, for we each keep our own spoon and pocket-knife in our pockets. We just lick them as clean as possible and replace them in our pockets after each meal.

"Our spoons are one of our indispensable possessions here. To lose one's spoon would be almost as serious as it is for an edentate person to lose his set of false teeth."

During all this time the supply of seals and penguins, if not inexhaustible, was always sufficient for our needs.

Seal- and penguin-hunting was our daily occupation, and parties were sent out in different directions to search among the hummocks and the pressure-ridges for them. When one was found a signal was hoisted, usually in the form of a scarf or a sock on a pole, and an answering signal was hoisted at the camp.

Then Wild went out with a dog team to shoot and bring in the game. To feed ourselves and the dogs, at least one seal a day was required. The seals were mostly crab-eaters, and emperor penguins were the general rule. On November 5, however, an adelie was caught, and this was the cause of much discussion, as the following extract shows: "The man on watch from 3 a.m. to 4 a.m. caught an adelie penguin. This is the first of its kind that we have seen since January last, and it may mean a lot. It may signify that there is land somewhere near us, or else that great leads are opening up, but it is impossible to form more than a mere conjecture at present."

No skuas, Antarctic petrels, or sea-leopards were seen during our two months' stay at Ocean Camp.

In addition to the daily hunt for food, our time was passed in reading the few books that we had managed to save from the ship. The greatest treasure in the library was a portion of the "Encyclopaedia Britannica." This was being continually used to settle the inevitable arguments that would arise. The sailors were discovered one day engaged in a very heated discussion on the subject of Money and Exchange. They finally came to the conclusion that the Encyclopædia, since it did not coincide with their views, must be wrong.

"For descriptions of every American town that ever has been, is, or ever will be, and for full and complete biographies of every American statesman since the time of George Washington and long before, the Encyclopædia would be hard to beat. Owing to our shortage of matches we have been driven to use it for purposes other than the purely literary ones though; and one genius having discovered that the paper, used for its pages had been impregnated with saltpetre, we can now thoroughly recommend it as a very efficient pipe-lighter."

We also possessed a few books on Antarctic exploration, a copy of Browning and one of "The Ancient Mariner." On reading the latter, we sympathized with him and wondered what he had done with the albatross; it would have made a very welcome addition to our larder.

The two subjects of most interest to us were our rate of drift and the weather. Worsley took observations of the sun whenever possible, and his results showed conclusively that the drift of our floe was almost entirely dependent upon the winds and not much affected by currents. Our hope, of course, was to drift northwards to the edge of the pack and then, when the ice was loose enough, to take to the boats and row to the nearest land. We started off in fine style, drifting north about twenty miles in two or three days in a howling south-westerly blizzard. Gradually, however, we slowed up, as successive observations showed, until we began to drift back to the south. An increasing north-easterly wind, which commenced on November 7 and lasted for twelve days, damped our spirits for a time, until we found that we had only drifted back to the south three miles, so that we were now seventeen miles to the good. This tended to reassure us in our theories that the ice of the Weddell Sea was drifting round in a clockwise direction, and that if we could stay on our piece long enough we must eventually be taken up to the north, where lay the open sea and the path to comparative safety.

The ice was not moving fast enough to be noticeable. In fact, the only way in which we could prove that we were moving at all was by noting the change of relative positions of the bergs around us, and, more definitely, by fixing our absolute latitude and longitude by observations of the sun. Otherwise, as far as actual visible drift was concerned, we might have been on dry land.

For the next few days we made good progress, drifting seven miles to the north on November 24 and another seven miles in the next fortyeight hours. We were all very pleased to know that although the wind was mainly south-west all this time, yet we had made very little easting. The land lay to the west, so had we drifted to the east we should have been taken right away to the centre of the entrance to the Weddell Sea, and our chances of finally reaching land would have been considerably lessened.

Our average rate of drift was slow, and many and varied were the calculations as to when we should reach the pack-edge. On December 12, 1915, one man wrote: "Once across the Antarctic Circle, it will seem as if we are practically halfway home again; and it is just possible that with favourable winds we may cross the circle before the New Year. A drift of only three miles a day would do it, and we have often done that and more for periods of three or four weeks.

"We are now only 250 miles from Paulet Island, but too much to the east of it. We are approaching the latitudes in which we were at this time last year, on our way down. The ship left South Georgia just a year and a week ago, and reached this latitude four or five miles to the eastward of our present position on January 3, 1915, crossing the circle on New Year's Eve."

Thus, after a year's incessant battle with the ice, we had returned, by many strange turns of fortune's wheel, to almost identically the same latitude that we had left with such high hopes and aspirations twelve months previously; but under what different conditions now! Our ship crushed and lost, and we ourselves drifting on a piece of ice at the mercy of the winds. However, in spite of occasional setbacks due to unfavourable winds, our drift was in the main very satisfactory, and this went a long way towards keeping the men cheerful.

As the drift was mostly affected by the winds, the weather was closely watched by all, and Hussey, the meteorologist, was called upon to make forecasts every four hours, and some times more frequently than that. A meteorological screen, containing thermometers and a barograph, had been erected on a post frozen into the ice, and observations were taken every four hours. When we first left the ship the weather was cold and miserable, and altogether as unpropitious as it could possibly have been for our attempted march. Our first few days at Ocean Camp were passed under much the same conditions. At nights the temperature dropped to zero, with blinding snow and drift. One-hour watches were instituted, all hands taking their turn, and in such weather this job was no sinecure. The watchman had to be continually on the alert for cracks in the ice, or any sudden changes in the ice conditions, and also had to keep his eye on the dogs, who often became restless, fretful, and quarrelsome in the early hours of the morning. At the end of his hour he was very glad to crawl back into the comparative warmth of his frozen sleeping-bag.

On November 6 a dull, overcast day developed into a howling blizzard from the south-west, with snow and low drift. Only those who were compelled left the shelter of their tent. Deep drifts formed everywhere, burying sledges and provisions to a depth of two feet, and the snow piling up round the tents threatened to burst the thin fabric. The fine drift found its way in through the ventilator of the tent, which was accordingly plugged up with a spare sock.

This lasted for two days, when one man wrote: "The blizzard continued through the morning, but cleared towards noon, and it was a beautiful evening; but we would far rather have the screeching blizzard with its searching drift and cold damp wind, for we drifted about eleven miles to the north during the night."

For four days the fine weather continued, with gloriously warm, bright sun, but cold when standing still or in the shade. The temperature usually dropped below zero, but every opportunity was taken during these fine, sunny days to partially dry our sleeping-bags and other gear, which had become sodden through our body-heat having thawed the snow which had drifted in on to them during the blizzard. The bright sun seemed to put new heart into all.

The next day brought a north-easterly wind with the very high temperature of 27° Fahr.—only 5° below freezing. "These high temperatures do not always represent the warmth which might be assumed from the thermometrical readings. They usually bring dull, overcast skies, with a raw, muggy, moisture-laden wind. The winds from the south, though colder, are nearly always coincident with sunny days and clear blue skies."

The temperature still continued to rise, reaching 33° Fahr. on November 14. The thaw consequent upon these high temperatures was having a disastrous effect upon the surface of our camp. "The surface is awful!—not slushy, but elusive. You step out gingerly. All is well for a few paces, then your foot suddenly sinks a couple of feet until it comes to a hard layer. You wade along in this way step by step, like a mudlark at Portsmouth Hard, hoping gradually to regain the surface. Soon you do, only to repeat the exasperating performance ad lib., to the accompaniment of all the expletives that you can bring to bear on the subject. What actually happens is that the warm air melts the surface sufficiently to cause drops of water to trickle down slightly, where, on meeting colder layers of snow, they freeze again, forming a honeycomb of icy nodules instead of the soft, powdery, granular snow that we are accustomed to."

These high temperatures persisted for some days, and when, as occasionally happened, the sky was clear and the sun was shining it was unbearably hot. Five men who were sent to fetch some gear from the vicinity of the ship with a sledge marched in nothing but trousers and singlet, and even then were very hot; in fact they were afraid of getting sunstroke, so let down flaps from their caps to cover their necks. Their sleeves were rolled up over their elbows, and their arms were red and sunburnt in consequence. The temperature on this occasion was 26° Fahr., or 6° below freezing. For five or six days more the sun continued, and most of our clothes and sleeping-bags were now comparatively dry. A wretched day with rainy sleet set in on November 21, but one could put up with this discomfort as the wind was now from the south.

The wind veered later to the west, and the sun came out at 9 p.m. For at this time, near the end of November, we had the midnight sun. "A thrice-blessed southerly wind" soon arrived to cheer us all, occasioning the following remarks in one of the diaries:

"To-day is the most beautiful day we have had in the Antarctic—a clear sky, a gentle, warm breeze from the south, and the most brilliant sunshine. We all took advantage of it to strike tents, clean out, and generally dry and air ground-sheets and sleeping-bags."

I was up early—4 a.m.—to keep watch, and the sight was indeed magnificent. Spread out before one was an extensive panorama of icefields, intersected here and there by small broken leads, and dotted with numerous noble bergs, partly bathed in sunshine and partly tinged with the grey shadows of an overcast sky.

As one watched one observed a distinct line of demarcation between the sunshine and the shade, and this line gradually approached nearer and nearer, lighting up the hummocky relief of the ice-field bit by bit, until at last it reached us, and threw the whole camp into a blaze of glorious sunshine which lasted nearly all day.

"This afternoon we were treated to one or two showers of hail-like snow. Yesterday we also had a rare form of snow, or, rather, precipitation of ice-spicules, exactly like little hairs, about a third of an inch long.

"The warmth in the tents at lunch-time was so great that we had all the side-flaps up for ventilation, but it is a treat to get warm occasionally, and one can put up with a little stuffy atmosphere now and again for the sake of it. The wind has gone to the best quarter this evening, the south-east, and is freshening."

On these fine, clear, sunny days wonderful mirage effects could be observed, just as occur over the desert. Huge bergs were apparently resting on nothing, with a distinct gap between their bases and the horizon; others were curiously distorted into all sorts of weird and fantastic shapes, appearing to be many times their proper height. Added to this, the pure glistening white of the snow and ice made a picture which it is impossible adequately to describe.

Later on, the freshening south-westerly wind brought mild, overcast weather, probably due to the opening up of the pack in that direction.

I had already made arrangements for a quick move in case of a sudden break-up of the ice. Emergency orders were issued; each man had his post allotted and his duty detailed; and the whole was so organized that in less than five minutes from the sounding of the alarm on my whistle, tents were struck, gear and provisions packed, and the whole party was ready to move off. I now took a final survey of the men to note their condition, both mental and physical. For our time at Ocean Camp had not been one of unalloyed bliss. The loss of the ship meant more to us than we could ever put into words. After we had settled at Ocean Camp she still remained nipped by the ice, only her stern showing and her bows overridden and buried by the relentless pack. The tangled mass of ropes, rigging, and spars made the scene even more desolate and depressing.

It was with a feeling almost of relief that the end came.

"November 21, 1915.—This evening, as we were lying in our tents we heard the Boss call out, 'She's going, boys!' We were out in a second and up on the look-out station and other points of vantage, and, sure enough, there was our poor ship a mile and a half away struggling in her death-agony. She went down bows first, her stern raised in the air. She then gave one quick dive and the ice closed over her for ever. It gave one a sickening sensation to see it, for, mastless and useless as she was, she seemed to be a link with the outer world. Without her our destitution seems more emphasized, our desolation more complete. The loss of the ship sent a slight wave of depression over the camp. No one said much, but we cannot be blamed for feeling it in a sentimental way. It seemed as if the moment of severance from many cherished associations, many happy moments, even stirring incidents, had come as she silently up-ended to find a last resting-place beneath the ice on which we now stand. When one knows every little nook and corner of one's ship as we did, and has helped her time and again in the fight that she made so well, the actual parting was not without its pathos, quite apart from one's own desolation, and I doubt if there was one amongst us who did not feel some personal emotion when Sir Ernest, standing on the top of the look-out, said somewhat sadly and quietly, 'She's gone, boys.'

"It must, however, be said that we did not give way to depression for long, for soon every one was as cheery as usual. Laughter rang out from the tents, and even the Boss had a passage-at-arms with the storekeeper over the inadequacy of the sausage ration, insisting that there should be two each 'because they were such little ones,' instead of the one and a half that the latter proposed."

The psychological effect of a slight increase in the rations soon neutralized any tendency to downheartedness, but with the high temperatures surface-thaw set in, and our bags and clothes were soaked and sodden. Our boots squelched as we walked, and we lived in a state of perpetual wet feet. At nights, before the temperature had fallen, clouds of steam could be seen rising from our soaking bags and boots. During the night, as it grew colder, this all condensed as rime on the inside of the tent, and showered down upon us if one happened to touch the side inadvertently. One had to be careful how one walked, too, as often only a thin crust of ice and snow covered a hole in the floe, through which many an unwary member went in up to his waist. These perpetual soakings, however, seemed to have had little lasting effect, or perhaps it was not apparent owing to the excitement of the prospect of an early release.

A north-westerly wind on December 7 and 8 retarded our progress somewhat, but I had reason to believe that it would help to open the ice and form leads through which we might escape to open water. So I ordered a practice launching of the boats and stowage of food and stores in them. This was very satisfactory. We cut a slipway from our floe into a lead which ran alongside, and the boats took the water "like a bird," as one sailor remarked. Our hopes were high in anticipation of an early release. A blizzard sprang up, increasing the next day and burying tents and packing-cases in the drift. On December 12 it had moderated somewhat and veered to the south-east, and the next day the blizzard had ceased, but a good steady wind from south and south-west continued to blow us north.

"December 15, 1915.—The continuance of southerly winds is exceeding our best hopes, and raising our spirits in proportion. Prospects could not be brighter than they are just now. The environs of our floe are continually changing. Some days we are almost surrounded by small open leads, preventing us from crossing over to the adjacent floes."

After two more days our fortune changed, and a strong north-easterly wind brought "a beastly cold, windy day" and drove us back three and a quarter miles. Soon, however, the wind once more veered to the south and south-west. These high temperatures, combined with the strong changeable winds that we had had of late, led me to conclude that the ice all around us was rotting and breaking up and that the moment of our deliverance from the icy maw of the Antarctic was at hand.

On December 20, after discussing the question with Wild, I informed all hands that I intended to try and make a march to the west to reduce the distance between us and Paulet Island. A buzz of pleasurable anticipation went round the camp, and every one was anxious to get on the move. So the next day I set off with Wild, Crean, and Hurley, with dog teams, to the westward to survey the route. After travelling about seven miles we mounted a small berg, and there as far as we could see stretched a series of immense flat floes from half a mile to a mile across, separated from each other by pressure-ridges which seemed easily negotiable with pick and shovel. The only place that appeared likely to be formidable was a very much cracked-up area between the old floe that we were on and the first of the series of young flat floes about half a mile away.

December 22 was therefore kept as Christmas Day, and most of our small remaining stock of luxuries was consumed at the Christmas feast. We could not carry it all with us, so for the last time for eight months we had a really good meal—as much as we could eat. Anchovies in oil, baked beans, and jugged hare made a glorious mixture such as we have not dreamed of since our school-days. Everybody was working at high pressure, packing and repacking sledges and stowing what provisions we were going to take with us in the various sacks and boxes. As I looked round at the eager faces of the men I could not but hope that this time the fates would be kinder to us than in our last attempt to march across the ice to safety.