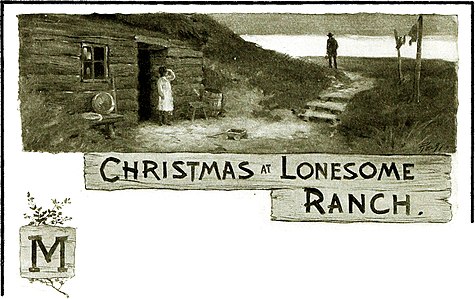

St. Nicholas/Volume 32/Number 3/Lonesome Ranch

By Anna E. S. Droke.

ary Ellen stood in the doorway, shading her face with her hands. Her face wore a faraway look, and she had ceased to watch the figure disappearing in the distance.

Mary Ellen's face frequently wore that look when she had a problem on her mind—and she usually had one. The problem of getting something out of nothing was ever present in some one of its varied phases; but to-day it was more than usually vexing, because Mary Ellen had fully made up her mind that something real had got to happen, She had been content with pretending just as long as she was going to, she told herself; and this time the twins were going to have something real for Christmas—something bought. How she was going to buy it was the yet unsolved question.

Just now her spirits were unusually low; for ever since her father had told her, on Saturday evening, that he had work for possibly two weeks repairing some barns at Fairview Ranch, she had been gathering courage to ask him if she might have a little—one dollar if possible, fifty cents at least—to buy something for Charlie and Charlotte, the twins, who did not remember Christmas in their Eastern home and could not understand why Santa Claus, of whom Mary Ellen never tired of telling them, never found his way to their lonesome dugout.

And now she had asked him, and he had said: “I ‘mm so sorry to disappoint you, little daughter; but we must have flour and fuel, and we all need shoes. It may be a long time before another job comes my way.” Then he kissed her and started to his work, with many misgivings at leaving his children alone until Saturday night; but the time consumed in going back and forth each day would mean extra hours with extra pay.

Nothing more dangerous than coyotes would be likely to visit them, and Mary Ellen would take care of them. Yes, Mary Ellen was a very capable child, John Morton told himself as he strode over the plains toward Fairview Ranch, five miles distant.

Poor Mary Fllen! Everybody who saw her said, “Poor Mary Hen!” She was thirteen, but small fer her age. She had never had time to grow—so people said. She was nine, and in the fourth grade at the district school, when she climbed up beside her father on the high seat of the bright new prairie-schooner, four years ago, and set out from her home in Indiana for the great West.

John Morton was a carpenter owning a little cottage and earning a fair living in the little Indiana town; but the desire to own a farm was upon him, so he sold his little home and, buying an outfit, set out for the unknown land.

“We will go on to the irrigated country,” he said. So into the great Arkansas valley, in southern Colorado, he took his way, homesteading a quarter-section in what seemed destined to be a promising location, Lumber for even a rude shanty would cat sadly into his little savings; so they camped in the wagon until the dugout was finished.

It seemed to Mary Ellen, when she took time to think, that she had never had time to straighten herself and take a good breath since she climbed down from the big wagon and took charge of the housekeeping; for the mother, who was delicate, was utterly prostrated by the long journey. During the winter her health improved; but the next summer an attack of mountain fever proved too much for her frail constitution, and Mary Ellen was left as mother and housekeeper to the little pioneer family.

Misfortunes had not come singly. Farming of any kind John Morton knew little of; farming by irrigation, nothing. At the end of this fourth year they were still living in the dugout. The wagon was gone; the horses were gone; only “Muley,” the faithful old cow, remained.

Mary Ellen, standing in the doorway that Monday morning in early December, caught sight of old Muley, and had an inspiration. She flew into the house with an enthusiasm that not even the prospect of two weeks’ loneliness at Lonesome Ranch could dissipate. Mary Ellen had christencd the place, and no one would deny that the name was appropriate. She lifted the lid of the stove and poked the fire; she flew from the lard-bucket to the molasses-jug; and made such a clatter that she woke the twins, whom she set to eat their breakfast, while she continued investigations.

“Yes,” sniffing at a little brown-paper parcel, “that’s ginger. I ’ll make ginger cookies and a teentsy bit of molasses candy; and every day for dinner I ’ll make the very nicest gravy they ever ate, Oh, I ‘ll manage, and I don’t believe the twins will ever miss the butter,”

“Sister, what are you going to p’tend now? I know you ‘re going to p’tend something nice, ’cause you always act that way when you ’ve thought of something nice.”

“Yes, Lottie; I ’m guing to p’tend now that I ’m the baker-man, and you and Charlie are to run over to Prairie Dog Town and see if there is any news, and when you come back I ‘ll have something nice to sell you.”

Prairie Dog Town was one of their frequent resorts. True, the prairie dogs always scuttled most inhospitably into their houses when they saw company coming; but the children were not sensitive, and continued their visits.

Many of the mounds had been named by Mary Ellen for people and places “back East.” Then there was the school-house and the post- office. This latter place was the center of interest, for here they frequently received pleasing bits of information, and last Valentine’s Day there had been some marvelous pasteboard hearts, ornamented with the red and green paper in which parcels had been wrapped, and bearing sweet little sentimental poems copied from the lace-and-roses ones Mary Ellen had received back East.

Since their arrival at Lonesome Ranch no holiday had been allowed to pass without some kind of an attempt, on Mary Ellen’s part, to celebrate it. Sometimes the meager little attempts were so pitifully pathetic that the father and mother had thought of hiding the—almanac, that Mary Ellen might nut know when they arrived. Since the death of his wife, all days were alike to John Morton, and the struggle for bread absorbed his thoughts.

Mary Ellen flew to her work with a light heart. “Two pounds of butter a week. I can safely count on old Muley for that. I know I can save one pound each week while father is gone, Butter is twenty-five cents a pound. I ’ll ask Mrs, Aletzger to let me go with her when she goes to La Junta to market. Two pounds of butter at twenty-five cents a pound—fifty cents. I must have two oranges, two big red apples, white sugar enough to make some little cakes and frost ’em. and red candy beads to trim ’em with, and a pair of mittens far Charlie, and if I could only get a pair of red stockings for Lottie!” Red stockings, for little girls, were just coming into vogue when Mary Ellen left the East, and one of the dreams of her life had been to possess a pair. She had no doubt they were still fashionable, and, having renounced such frivolities herself, she longed, with the instinct of the little mother, to have a pair for Lottie.

“Dear me! I wonder what all those things would cost? More than fifty cents, I ’m afraid. As soon as I roll out these cookies and get a pencil I will figure it all out.”

But she finally surrendered all hope of anything save the mittens and stockings, and determined to ask her father for ten cents with which to buy the sugar. When, at the end of two weeks, Mary Ellen displayed her two plump rolls of butter and told her story, her father stroked her brown hair tenderly as he said: “You are a very resourceful girl, Mary Ellen—very resourceful!”

Mary Ellen did not know exactly what this meant, but she was sure her father was not displeased with her, for he had said the same to her once before—once when she felt sure he had been pleased with her efforts.

It was Saturday, six days before Christmas, when Mary Ellen, proudly carrying her two pounds of butter, set out with Mrs. Metzger for La Junta. Frau Metzger was a kindly, big German woman, childless, and not given to sentimentality; but when she heard the story of the pounds of butter, and learned of the articles Mary Ellen had fondly hoped to buy with the proceeds, she felt a-strange pulling at her heartstrings, and she said:

“Just before leaving, kind old Frau Metzger went into the room where Mary Ellen was sleeping.” (See page 262.)

“And with two pounds of butter and ten cents you would make one bright Christmas for the little ones! Still, I know of one better way. Santa Claus has himself sent me word, asking me to help him this year, already, I will myself hook Charlie one pair of mittens with the woolly wrists. I have at home beautiful red yarn, and I will knit stockings for the little Mädchen—I and the girl Nora. She is most wonderful to knit, You shall buy, with the money, the other things.”

A queen with untold wealth could have felt no richer than did Mary Ellen as she made her purchases. Luscious oranges, great red apples,—four of each instead of two,—candy and peanuts, and plenty of sugar for the cakes.

When they drove into La Junta the air was balmy as springtime, and the sun was shining in an unclouded sky; but the storm-signal was waving. Before they started homeward the storm was upon them.

The storekeeper wrapped the child

“When the children were safely out of the way, Mary Ellen sometimes climbed up in a chair and lifted it down.” (See page 263.) as well as he could in the heavy robe. They were facing the

storm: every moment it grew colder. They had gone scarcely five miles when Mary Ellen, striving with her unmittened hands to

hold the fur robe around her, felt herself growing numb. Through her chattering teeth she uttered the fear that the apples and oranges would freeze.

“Give them here, once; I’ll keep ’em safe.” Frau Metzger opened the great ulster and tucked them safely inside it.

Responsibility gone, the child began to relax. She dreamed that the great brown ulster had opened and swallowed her bodily, and she was just nestling down so warm and comfortable, when she was aroused by a vigorous shaking, only to sink again into blissful repose.

Dark, not more than half-way home, and the child freezing—this was the situation. Mrs. Metzger’s thoughts traveled rapidly. There was but one refuge. It could be only a short distance to Crazy Bill’s shanty.

“Crazy Bill, or Wild Bill, or whatever Bill they call ‘im, I ’m sure he would n‘t harm the child; and, anyhow, his wife would n’t let him. Mrs. Crazy Bill will take good care of her, I know, for she is fond of children. To take her on m this storm is sure death; to leave her could be no more.” She halted and called, but no voice could be heard against the howl of the storm. She laid the child in the bottom of the wagon and made her way toward the light.

When the man learned that a child was freezing at his door, he went out without a word and carried her in. His wife took charge of her at once, with many a kindly “Poor dear!” as she took off her cloak and drew her near the fire, patting her cold hands the while. Restoratives were applied, and in a short time Mary Ellen returned to consciousness. Riding the remaining five miles, however, was not to be thought of for her; so Mrs. Metzger explained to her, concluding with: “You stay here the night with Mrs. William, and in the morning, if I don’t freeze myself gettin’ home, I ’ll fetch you, still.”

“I ’ll take her myself,” said the man, cordially.

“Then I ’ll be leavin’ the Christmas tricks for herself to carry along,” said Frau Metzger, depositing the fruit on the kitchen table.

“Was it Christmas buyin’ as took the child out?”

“Ay, and such riches, you ’d never count ’em.” Then, as she warmed her feet in the oven and drank the hot tea prepared for her, Mrs. Metzger told Crazy Bill and his wife of the Christmas that was in prospect for the children at Lonesome Ranch. “And never a thought for herself, mind ye. She ’s forty, if she’s a day, the little old mother.”

Just before leaving, kind old Frau Metzger, with her basket on her arm and wrapped in a great blanket cloak, went into the room where Mary Ellen was by this time sleeping and bent over the cot. She thought of another little girl of long ago, back in Germany, and her kind old heart went out to this lonesome American child. Impulsively she drew from her basket a doll that had been intended for little Charlie, and was about to lay it on the coarse straw pillow. “But no,” she said to herself; “it's only one day; it would only spoil Charlie’s Christmas surprise, and I have something better for her at home”; so she returned it to her basket and tiptoed out of the room.

“When he opened the door a small mountain spruce fell forward into the room.”

The next morning Mary Ellen was set down, safe and sound, at her father’s door, and loiterers about the depot in La Junta noticed Crazy Bill as he boarded the evening train.

“A little tip to Denver for my health,” was the answer he gave his cow-boy friends.

Fortune favored Mary Ellen with sunny days, so that the children were rarely in the house, and her preparations went on finely. The little cakes were baked and trimmed, and truly they were little beauties. They were hidden, with all the other surprises, in the big, green paste-board box on the top shelf of the cupboard. When the children were safely out of the way, Mary Ellen sometimes climbed up in a chair and lifted it down. She patted the cakes and sniffed at the luscious oranges and great, rosy apples, and laughed to think what fun it would be to be putting one in her own stocking.

“It would be like Christmas back East, if only there was a little cedary smell mixed with the other smells; but I don’t suppose there

ever was any cedar out here.” Then, hearing the children coming, she would hastily put the cover on and return the box to its place.

The day before Christmas, Mrs. Metzger drove over with the promised mittens and stockings. She brought also a fat hen and a can of peaches, which she laughingly told Mary Ellen she could put into her own stocking.

On Christmas Eve the children went early to bed, for they had been to the post-office at Prairie Dog Town that morning, and brought back a letter saying that Santa Claus would surely visit them this year,

Mary Ellen and her father sat, one on each side of the stove, waiting in silence for the children to go ta sleep; and long after their regular breathing reported the children in Slumberland, they continued to sit, neither speaking, each busy with thoughts of other days

Then there came a knock at the door. The man called, “Who's there?” and hastily struck a light. There was no answer; and when he opened the door a small tree of mountain spruce, which completely blocked the doorway, fell forward into the room.

When he lifted it up, the sweet, pungent odor so overcame Mary Ellen that she threw herself face foremost on the bed and cried, which was a very unusual thing for her to do.

When her father called to her, she quickly jumped up to assist him. There was also on the door-step a great box of presents, and dozens of tapers with which to light the tree. When the box was opened, Mary Ellen could scarcely stifle screams of delight as she viewed the wonderful tops, drums, guns, boats, and balls—the dolls and dishes such as Mary Ellen had sometimes seen in the shop windows, but had never possessed.

There were many useful presents, too; but when one imposing-looking bundle, bearing the address, “To the little mother, with love, from Mrs. William,” was opened, and proved to be a doll more than two feet long, having real hair and opening and shutting its eyes and talking,—“really and truly talking,’—it was then that Mary Ellen was too overcome for words. It seemed to be a “doll day” at Lonesome Ranch, for good old Mrs. Metzger had included with her gifts a cunning little brown-eyed, brown-haired doll for Charlotte, and a funny-looking boy doll who struck together little brass cymbals fastened to his hands whenever you pressed his stomach.

The tree was dressed and lighted. The children were wakened, and it was hard for them to realize that they were not still dreaming of Santa Claus and fairyland.

Long after Mary Ellen had crept tired to bed, with “Cinderella Josephine” clasped close in her arms, she bethought her of the presents in the pasteboard box,

“I ‘ll keep them for the morning; and, most likely, if we had n’t been going to have them, we should never have bad this lovely Christmas Eve: I'll always think it was good Mr. and Mrs, William—I can’t call him Crazy Bill any more—who brought the tree and the beautiful presents—was n’t it, Cinderella Josephine?” And Cinderella Josephine, when her little mother touched the right button, said, “Yes, mama,” and then they both went sound asleep.