Star Lore Of All Ages/Canis Major

Canis Major

The Greater Dog

The Greater Dog

Canis Major has been considered from earliest times one of the dogs the giant Orion took with him when he went hunting. Some, however, claim the constellation received its name in honour of the dog given by Aurora to Cephalus, which was the swiftest of his species. The legend relates that Cephalus raced the hound against a fox, which was considered the fleetest of all animals. After they had raced for some time without either obtaining the lead, Jupiter was so much gratified with the fleetness displayed by the dog that he immortalised him by giving him a place among the stars. Another story claims that this was the dog of Icarius.

Among the Scandinavians Canis Major was regarded as the dog of Sigurd, and in ancient India it was called "the Deerslayer." Although mythology connects this star group with the dog of Orion, Sirius, the brightest star in the constellation, seems to have been associated with the idea of a dog even among nations unacquainted with the myth of Orion. In the famous zodiac of Denderah, Canis Major appears in the form of a cow in a boat. It also figures on an ivory disk found on the site of Troy, and on an ancient Etruscan mirror.

According to Burritt, the name and form of the constellation was derived from the Egyptians, who carefully watched its rising, and by it judged of the swelling of the Nile, which they called "Siris."

In the early classical days, says Allen, it was simply "Canis," and represented "Lælaps," the hound of Acteon, or that of Diana's nymph Procris. Homer called it κύων but this doubtless was a reference to the star Sirius. Novidius called it "the Dog of Tobias," and Dr. Seiss regarded Canis Major as "the Appointed Prince."

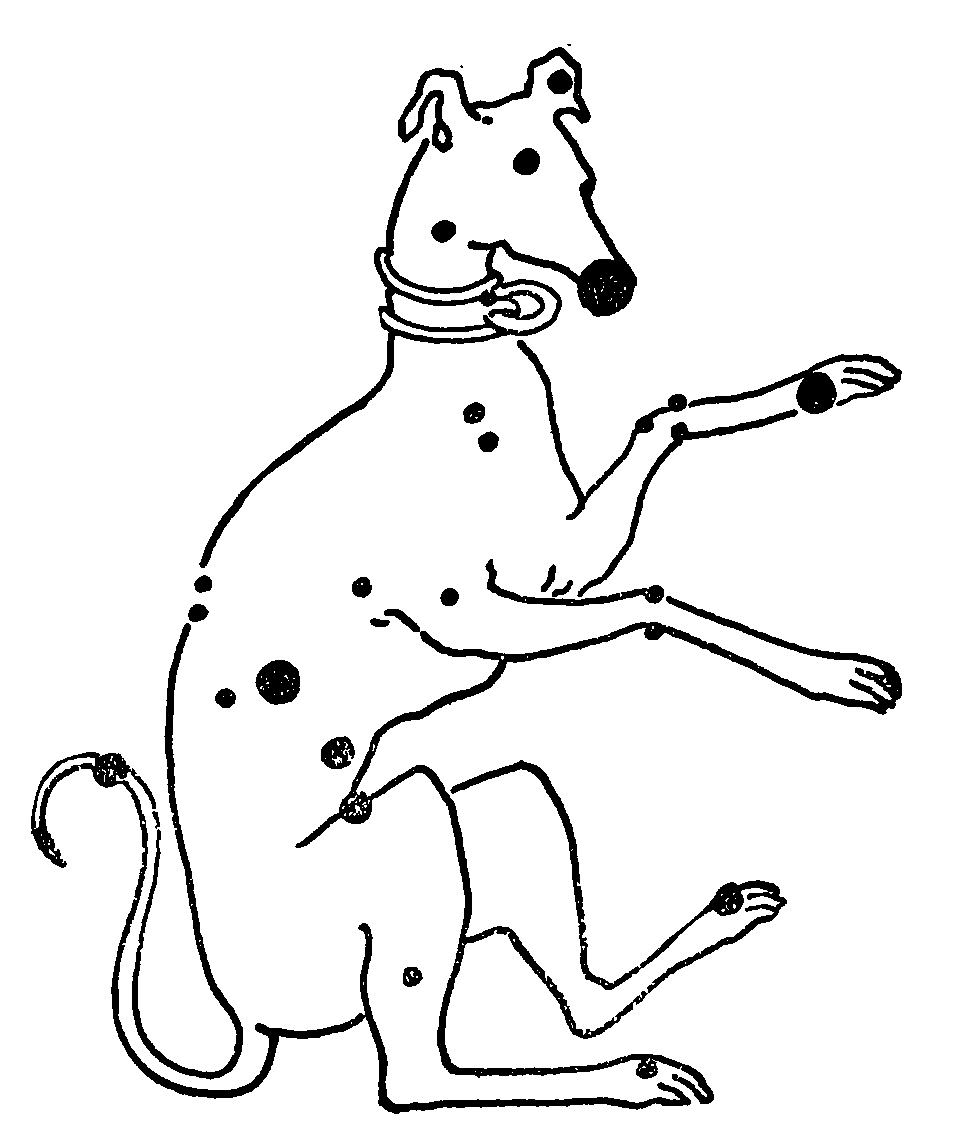

On the maps, the Dog is generally pictured as standing on his hind feet watching or springing after the Hare, which cowers close under Orion's feet. Bayer and Flamsteed differ from all others in depicting Canis Major as a bulldog. Prof. Young describes "the Greater Dog" as one "who sits up watching his master Orion, but with an eye out for Lepus."

Aratos referring to Canis Major writes: "His body is dark but a star on his jaw sparkles with more life than any other star." This is of course a reference to Sirius, the brightest of all the fixed stars, and probably the star which has attracted the most universal attention of all the heavenly hosts.

In the early histories and inscriptions we find many astronomical references to "the Dog," but it is uncertain whether the constellation or the star Sirius is intended. The Arabian astronomers called the constellation "AlKalb-al-Akbar," meaning "the Greater Dog." In the Euphratean star list Canis Major is styled "the Dog of the Sun." Early Christians thought the figure represented Tobias's dog or St. David.

The importance of the constellation is overshadowed by the fame of its lucida, Sirius, the "King of Suns," concerning which star volumes have been written. Its matchless brilliancy has inspired the poets of all ages, and historically Sirius is beyond question the most interesting of all the stars in the firmament.

Aratos thus refers to Sirius:

In his fell jaw Flames a star above all others with searing beams Fiercely burning, called by mortals Sirius.

Eudosia writing of the Greater Dog says, "His fierce mouth flames with dreaded Sirius," and Victor Hugo in The Vanished City thus alludes to the might of this kingly star:

When like an Emir of tyrannic power Sirius appears and on the horizon black Bids countless stars pursue their mighty track.

Aside from the fact of its surpassing brilliance, the fact that Sirius is visible from every habitable portion of the globe has served to make it from time immemorial the nocturnal cynosure of all the nations of the earth.

The sight of this majestic star, clad as it were in all its wealth of history, rising over the snow-crowned hills on a crisp winter's night, flashing to us like a great beacon a message from infinite space, in letters of rainbow hue, is one of entrancing beauty.[1]

The name Sirius is supposed to be derived from the Greek word σείριος which signifies brightness and heat. It is thought by some to represent the three-headed dog Cerberus, who guarded the entrance to Hades, according to Greek mythology.

Allen states that the risings and settings of Sirius were regularly tabulated in Chaldea about 300 b.c., and that it is the only star known to us with absolute certitude in the Egyptian records, its hieroglyph often appearing on the monuments and temple walls throughout the Nile country.

According to Blake,[2] the hieroglyphics representing Sinus varied in accordance with the different functions the Egyptians ascribed to the star. "When they wished to signify that it opened the year, it was represented as a porter bearing keys, or else they gave it two heads, one of an old man to represent the passing year, and the other of a younger to denote the succeeding year. When they would represent it as giving warning of the inundation of the Nile they painted it as a dog. To illustrate what they were to do when it appeared Anubis had in his arms a stew-pot, wings to his feet, a large feather under his arm, two reptiles, a tortoise and a duck behind him."

Mrs. Martin thus alludes to this glorious sun: "He comes richly dight in many colours, twinkling fast, and changing with each motion from tints of ruby to sapphire and emerald and amethyst. As he rises higher and higher in the sky he gains composure and his beams now sparkle like the most brilliant diamond, not pure white but slightly tinged with iridescence."

Blake gives us the following interesting description of Sirius in the role of herald of the inundation of the Nile:

"This star seems to have been intimately connected with Egypt and to have derived its name from that country, and in this way: The overflowing of the Nile was always preceded by an Etesian wind (that is an annual periodic wind answering to the monsoons) which, blowing from north to south about the time of the passage of the sun beneath the stars of the Crab, drove the mists to the south, and accumulated them over the country whence the Nile takes its source, causing abundant rains, and hence the flood. The greatest importance was attached to the foretelling the time of this event, so that the people might be ready with their provisions, and their places of security. The moon was no use for this purpose, but the stars were, for the inundation commenced when the sun was in the stars of the Lion. At this time the stars of the Crab just appeared in the morning, but with them at some distance from the ecliptic, Sirius rose. The morning rising of this star was a sure precursor of the inundation. It seemed to them to be a warning star by whose first appearance they were to be ready to move to safer spots, and thus acted for each family the part of a faithful dog, whence they gave it the name of 'the Dog' or 'Monitor,' in Egyptian 'Anubis,' in Phcenician 'Hannobeach.'"

Sirius, on account of this great service which it rendered the Egyptians, was held in great reverence by them and called "the Nile Star." Under the name Anubis it was deified and this god was emblematically represented by the figure of a man with the head of a dog. It was also worshipped under the names "Sothis" and "Sihor."

Sirius was furthermore known to the Egyptians as "Isis" and "Osiris." If the first letter is omitted from this latter appellation we get "Siris," a name very similar to the modern title of the star.

Other Egyptian names for the star were "Thoth" or "Tayaut" meaning "the Dog," "Hathor," the barker, the monitor, and at Philæ it was called "Sati."

Sirius was worshipped in the valley of the Nile long before Rome had been heard of. In its honour many temples were erected so magnificent in their architectural proportions as to excite wonder and amazement even in this age of noble edifices.

Lockyer found seven Egyptian temples so arranged that the beams from this brilliant star in its rising or setting penetrated to the inner altar, the holy of holies. This feature of architecture is called orientation. Notable among these temples oriented to Sirius was the temple of Isis at Denderah, where Sirius was known as "Her Majesty of Denderah." Here the rising beams of Sirius flashed down the long vista of the massive pylons, and illumined the inner recesses of the temple. What a wonderful sight there must have been enacted within that darkened edifice when, in the presence of a vast multitude silent in meditation, there suddenly appeared a beam of silver light, that laved the marble altar in a refulgence born of the depths of the infinite, a beam, although the watchers knew it not that started on its earthward journey eight and a half years before it greeted their eyes!

The temple priests, versed to some extent in astronomical lore, knew well the psychological moment of the appearance of the light, and doubtless to further increase their prestige, and convey the idea that they were endowed with supernatural powers, so ordered the ritual that the greatest possible superstitious effect would be brought about by the seeming apparition. The awe inspired by the silence of the multitude worked up to a fever pitch of expectancy, and the excitement born of their desire to witness what they must have regarded as a manifestation of divine power, all conduced to make the moment one long to be remembered, and the event one of the greatest possible significance to the race.

It has been determined that the Babylonian star named "Sukudu" or "Kaksidi" was Sirius, for we are told that it was one of the seven most brilliant stars and a star of the south. The same star is also called "directing star" because connected with the beginning of the year.

According to Lockyer, Sirius rose cosmically, or with the sun, in the year 700 b.c. on the Egyptian New Year's Day. In mythological language "she mingled her light with that of her father Ra [the sun] on the great day of the year." This is the first instance of the personification of a star.

"It is possible" says Maunder, "that the two great stars which follow Orion—Sirius and Procyon, known to the ancients generally and to us to-day as 'the Dogs'— were by the Babylonians known as 'the Bow Star' and 'the Lance Star' respectively, the weapons that is to say of Orion or Merodach." Jensen also identifies Sirius with the Bow Star.

Homer compared Sirius to Diomedes' shield, and called it "the Star of Autumn."

Homer regarded Sirius as a star of ill omen, as it was supposed to produce fevers. Pope's translation of Homer's lines indicates the baleful influence ascribed to Sirius:

The description of the rising of this star is the only indication in the Homeric poems of the use of a stellar calendar.

Manilius seems to have had two views respecting Sirius. In one place he writes:

In another we find:

The Arab name for Sirius was "Al-Shira-al-jamânija," meaning "the bright star of Yemen." Gore thinks that the word "Shira" might have been corrupted in the course of time into Sirius. Al-Shira was also interpreted "the Doorkeeper," Sirius being regarded as the star which opens or shuts. The Arabs also called this star "the Dog Star." In modern Arabia it is "Suhail," the general designation for bright stars.

The so-called "Dog Days" got their name from the fact that in the hottest days of summer Sirius, the Dog Star, blends his piercing rays with those of the god of day. This is of course metaphorical, as the heat we receive from Sirius is inappreciable.

According to Max Müller, the special Indian astronomical name of the Dog Star signified a hunter and deer-slayer. He is of the opinion that Sirius was called the Dog Star on account of the prevalence of canine madness in the summer season.

Sirius has been appropriately called "the sparkling star" or "Scorcher," and the sun and Sirius have been called "wandering stars." It has been thought that Sirius is identical with the Mazzaroth mentioned in the Book of Job.

It seemed to be the prevailing idea among the ancient Eastern nations that the rising of Sirius would be coincident with a period of heat and pestilence. Virgil well describes the state of affairs when Sirius mingled his beams with those of the day-star.

Hesiod, who was the first to mention Sirius, wrote in like vein: "When Sirius parches head and knees and the body is dried up by reason of heat, sit in the shade and drink."

Such advice was doubtless as popular then as now during the dog days.

Euripides also refers to the fiery nature of Sirius, describing the star as "sending flames of fire drawn from the heavens."

Apollonius Rhodius speaks of Sirius "burning the islands of Minos."

Horace says: "Here in a quiet valley you will escape the heat of the Dog Star," and in his celebrated ode to the Bandusian Fount he writes:

The question whether Sirius has changed in colour since early times has given rise to considerable controversy. Ptolemy called it fiery red, Seneca claimed it was redder than Mars. Cicero also mentions its ruddy light, and Tennyson wrote:

Dr. See, the eminent astronomer of the present day, asserts that eighteen hundred years ago Sirius was red. There is a reference in Festus to the effect that the Roman farmers sacrificed ruddy or fawn-coloured dogs to save the fruits on account of the Dog Star, and Dr. See says there is no reason why the Romans should sacrifice red dogs except that Sirius was red, and dogs of the same colour must be offered up to the Dog in the sky. There can be no doubt that many of the ancients looked upon red stars as angry deities. Now Sirius is a white star with a bluish tinge, and Allen says that the weight of authority respecting the change in colour of Sirius seems to negative the idea that there has been any change.

Some writers identify the Masonic emblem of the Blazing Star with Sirius, the most splendid and glorious of all the stars,

Topelius, the Finnish poet, fancifully imagines that the great brilliancy of Sirius is due to the combined light of two stars, represented as lovers meeting and embracing:

Although the poet's idea is born of fancy there is nevertheless truth in the statement that we receive from Sirius the combined light of two stars, for Sirius has a faint companion visible only in the most powerful telescopes, and the discovery of this star furnishes an interesting chapter in astronomical history.

The famous German astronomer Bessel expressed his belief about seventy years ago, after ten years of observation, that the periodical variations in the motion of Sirius was produced by the attraction of an invisible companion, revolving around the gigantic star. On Jan. 31, 1862, Alvan G. Clark, at Cambridge, Mass., while testing the l8j½" glass for the Dearborn Observatory at Chicago, pointed the glass at Sirius, when the disturbing companion came suddenly into view at a distance of about 10 seconds from Sirius, and exactly in the direction predicted for that time.

The period of revolution of the companion around Sirius was found to be nearly fifty years, and within a few months of the time calculated by Bessel, long before the telescope had revealed its presence. The mass of Sirius is about twice the mass of its companion, yet its light is 40,000 times greater.

The following facts concerning Sirius may be of interest:

We know now that the brightness of a star is no indication of its distance from us, but Sirius which is 9½ times brighter than a standard first magnitude star is only 8½ light years away, and only four other stars are known to be nearer.

If our sun occupied the place of Sirius in the sky, it would appear as a third magnitude star.

There is considerable discrepancy among the authorities as to the size and brilliance of Sirius as compared with the sun. Its diameter is given as fourteen or eighteen times that of the sun. As regards its brightness, Newcomb states that Sirius is thirty times brighter than the sun, a modest estimate, as other authorities claim for Sirius a brilliance of forty, sixty-three, two hundred, and even three hundred times that of the day-star.

The spectroscope reveals that Sirius is completely enveloped in a dense atmosphere of hydrogen gas. It is the brightest of the so-called Sirian stars, the spectroscopic type I., which includes more than half of all the stars yet studied.

Sirius has a large proper motion—that is the angular change in the position of a star athwart the line of vision— as compared with the average proper motion of stars of the first magnitude. It amounts to 1.31″. In this connection it is interesting to note Al-Sufi's statement concerning the Arab name for Sirius, "Al-abûr." According to this noted astronomer Sirius was so-called because it had passed across the Milky Way into the southern region of the sky. It is a remarkable fact that the proper motion of Sirius would have carried it across the Milky Way from the eastern to the western border in 60,000 years. Possibly the Arabian story may be based on a tradition of Sirius having been seen on the opposite side of the Milky Way by the men of the Stone Age.

It is generally conceded that this star is receding from us, its rate of speed given variously by different authorities as from eighteen to forty miles a second. It comes to the meridian at 9 p.m., Feb. 11th.

The Arab names and meanings of the principal stars in Canis Major, Sirius excepted, are appended:

| Name | Meaning | |

| β | Murzim | the Announcer |

| δ | Wezen | Weight |

| ε | Adara | the Virgins |

| ξ | Furud | the Bright Single One |

| η | Aludra | the Virgin. |

- ↑ Serviss thus mentions Sirius: "The renown of Sirius is as ancient as the human race. There has never been a time or a people in which or by whom it was not worshipped, reverenced, and admired. To the builders of the Egyptian temples and pyramids it was an object as familiar as the sun itself."

- ↑ Astronomical Myths, by J. F. Blake.