Syria, the Land of Lebanon/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V

ACROSS THE MOUNTAINS

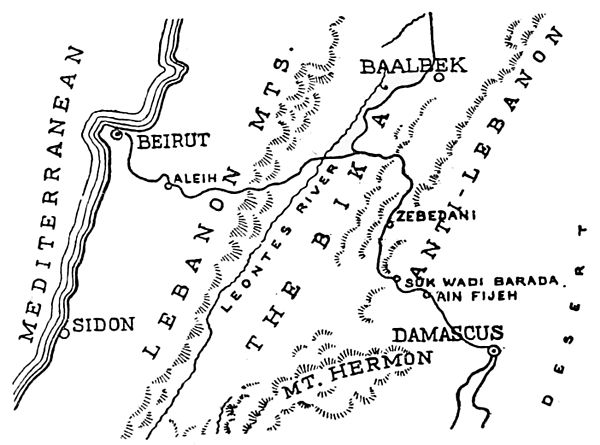

RAILWAYS and carriage-roads In Syria are chiefly due to French enterprise. The Société Ottomane des Chemins de Fer de Damas, Hama et Prolongements has less rolling stock than its lengthy name might lead one to expect, and its slow schedule is not always observed with a mechanical Western exactness. Although Damascus is barely fifty miles from Beirut, the journey thither takes ten hours; for the constantly curving railway measures more than ninety miles and the total rise of its numerous steep grades is over 7,000 feet. This single, narrow-gauge road, which is carried over two high mountain ranges, is an admirable example of modern engineering, and the scenery through which it passes is a source of unbroken delight.

As we zig-zag up the western slope of Lebanon there appear, now at our right and now at our left, a succession of beautiful panoramas which differ one from the other only in revealing a constantly widening horizon. Rich, populous valleys, lying deep between the shoulders of the mountains, slope quickly downward to the coast where, farther and farther below us, the silvery-green olive orchards and golden sands of Beirut reach out into the ever-broadening azure expanse of the Mediterranean.

Sometimes great masses of billowing clouds drift up the valleys, so that for a while we seem to be traveling along a narrow isthmus between foaming seas. The people of Aleih—a charming summer resort where the mountainside is so steep that there is no room for a curve and the train has to back up the next leg of the ascent—are the butt of many a popular tale. One day, so the wits of the neighboring villages relate, these foolish fellows mistook the rising tide of mist for the sea itself, and the whole populace prepared to go fishing.

Another time a number of residents of Aleih went to Beirut to buy shoes. On their way back they all sat on a wall to rest; and when they were ready to go on again, behold, the new shoes were all exactly the same size, shape and color, and no man could tell which of the feet were his. So there they sat, in sad perplexity as to how they should ever reach home, until a passer-by, to whom they explained their difficulty, smote the shoes smartly one after the other with his stick and thus enabled each person to recognize his own feet.

A third Aleih story also exemplifies the ridiculous exaggeration which so delights a Syrian audience. It seems that the only public well in the village used to be the subject of frequent quarrels between the inhabitants of the upper and lower quarters. So finally the sheikh stretched a slender pole across the middle of the opening and commanded that thenceforth each of the two opposing factions was to draw only from its own side. For a time all went peace-

ably; but one dark night a zealous partisan was discovered diligently at work dipping water from the farther side of the pole and pouring it into his half of the well!

Shortly after leaving Aleih, the train turns straight east and climbs with labored puffings up the shoulder of Jebel Keneiseh to the watershed, 4,800 feet above Beirut. It is very much cooler now. In midsummer, refreshing breezes blow down from unseen snow-banks among the mountaintops. In winter—if, indeed, the traffic is not entirely blocked by drifts which choke the railway cuts—the journey is memorable for its piercing, inescapable cold, and the natives who gather idly at the stations wear heavy sheepskin cloaks and keep their heads and shoulders swathed in thick shawls, though, strangely enough, their legs may be bare and their frost-bitten feet protected only by low slippers.

At last the jolting of the rack-and-pinion ceases, the train quickens its speed, passes through two short tunnels, swings around a high embankment; and over the crests of the lower hills we see a long, narrow stretch of level country, bordered on its farther side by a wall-like line of very steep mountains. The profile of the "Eastern Mountains"—as we behold them from this point we can hardly avoid using the Syrian name for Anti-Lebanon—seems almost exactly horizontal, and the resemblance of the range to a tremendous rampart is heightened by the massive buttresses which reach out at regular intervals between the courses of the winter torrents.

The valley before us is that which the Greeks named Coele-Syria or "Hollow Syria." In modern Arabic it is called the Bika' or "Cleft." Just as in Palestine the Jordan River and its two lakes are hemmed in by mountains which rise many thousand feet above, so in Syria the Bika' stretches between the parallel ranges of Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon. There is, however, one striking difference between the two valleys. That of the Jordan is a deep depression, and the mouth of the river is nearly 1,300 feet below the surface of the Mediterranean. On the other hand, the central valley of Syria throughout its entire length lies considerably above sea-level, and at its highest point reaches an elevation of about 4,000 feet. The Bika', which is seventy miles long

Conventionalized cross-section of Syria from Beirut (B) to Damacus (D). The horizontal distances are marked in miles, the vertical in feet.

and from seven to ten miles wide, is exceedingly fertile, and in it rise the two largest rivers of Syria. Near their sources the Orontes and Leontes pass within less than two miles of each other; yet the former flows to the north past Hama and Aleppo, while the latter turns southward and reaches the Mediterranean between Tyre and Sidon.

The Bika' extends north and south as far as we can see and is apparently as level as a floor. There are hardly any trees on it, only two or three tiny hamlets and no isolated buildings. The Syrian farmers prefer to dwell on the hillsides; for there the water of the springs is cooler, it is easier to guard the villages against marauding bands, and all of the arable land below is left free for cultivation. So the great flat fields of plowed earth or ripening grain which fill the valley seem the pattern of a long Oriental carpet in rich reds and browns and greens and yellows, unrolled between the mountains.

As we pass from the shadow of a last obstructing embankment, there bursts upon our vision the glorious patriarch of Syrian peaks. Twenty-five miles to the south the splendid crest of Hermon towers into the cloudless sky a full mile above the surrounding heights.

The familiar Hebrew name of this famous mountain means the "Sacred One," and the expression "the Baal of Hermon,"[1] seems to indicate that in very ancient times it bore a popular shrine. The Jews also knew it by its Amorite title Senir, the "Banner." Modern Syrians sometimes refer to it as the "Snow Mountain," for its summit is capped with white long after the summer sun has melted the drifts from the lower peaks. Most commonly, however, it is called esh-Sheikh, which means "the Old Man," or rather "the Chieftain," for age and authority are indissolubly associated in the thought of the Arabic-speaking world.[2]

Hermon is by far the most conspicuous landmark in all Palestine and Syria. I have seen it from the north, south, east and west. I have admired it from its own near foothills and from a hundred and fifty miles away. Viewed from every side it has the same shape — a long, gently rising cone of wonderful beauty; wherever you stand, it seems to be squarely facing you; and from every viewpoint it dominates the landscape as do few other mountains in the world.

This sacred peak influenced the religious idealism of many centuries. Upon its slopes lay Dan, the farthest point of the Land of Promise. "From Dan to Beer-sheba," from the great mountain of the north to the wells of the South Country, stretched the Holy Land. Hebrew poets and prophets sang of the plenteous dew of Hermon, its deep forests, its wild, free animal life. Upon its rugged shoulders the Greeks and Romans continued the worship of the old Syrian nature-gods. Hither, in the tenth century, fled from Egypt Sheikh ed-Durazy and made it the center of the new Druse religion. Above its steep precipices the Crusaders built two of their largest castles. But one most solemn event of all uplifts the sacred mountain even closer to the skies; for on some unnamed summit of the "Chieftain" the supreme Leader stood when the heavens opened for His transfiguration.

We cross the valley rapidly to the junction-station of Rayak and then, again ascending, penetrate the Eastern Mountains by a winding river-course which, as we follow it higher and higher, affords fine views over the Bika' to the range of Lebanon through which we were so long traveling. Directly opposite us stands Jebel Keneiseh, bare, brown and forbidding, while beside it rises the loftier Sunnin. When viewed from the coast, this noble mountain reveals one long, even slope to its topmost crest; but its back is made up of a multitude of rounded eminences, so that it resembles an enormous blackberry. Twenty miles to the north of Sunnin, near the famous Cedars of Lebanon, the range culminates in a group of snow-capped peaks which lack the impressiveness of Hermon's haughty isolation, yet which actually rise two thousand feet above even the Sheikh Mountain.

After crossing the watershed of Anti-Lebanon, we turn south through the lovely little vale of Zebedani. At our left are the highest summits of the range; at our right are precipitous cliffs which, save for a glimpse of the snows of Hermon, shut off the distant view; but between these heights is a scene of quiet, comfortable beauty. The tract is well-watered and fertile, and its wheat-fields are as level as the surface of a lake. Indeed, there surely must have been a lake here once upon a time. Along the eastern edge of the grain-land are charming, green-hedged gardens and closely planted orchards and long lines of poplar trees, while low-bent vines hug the sunny slopes at the mountain's foot. This high but sheltered valley is one of the few places in Syria where really fine apples are grown, and the grapes and apricots of Zebedani are famous throughout the whole country.

In a small marshy lake among the hills that border the rich, slumbrous little plain there rises one of the world's greatest rivers; great not in size—at its widest it is hardly more than a mountain brook and no ship has ever sailed its waters—but great because it has made one of the proudest cities of earth; for this slender stream which winds so leisurely through the wheat-fields of Zebedani is the far-famed Abana, and Abana is the father of Damascus.

At the lower end of the valley, the brook turns sharply eastward through a break in the mountains, and we follow it swiftly down a succession of narrow chasms and wild ravines, all the way to the end of our journey. The first two hours of our ride we traveled but twelve miles: the last two hours we slide forty miles around short, confusing curves. Sometimes there are distant views of bare, reddish summits; often we are hemmed in by the dense growth of trees which border the stream; but we are never far from the rushing waters of the Abana.

There is ancient history along our route, not to speak of legends innumerable. The little village of Suk Wadi Barada or "Barada Valley Market," was once called Abila, and was the chief city of the Tetrarchy of Abilene, the fixed date of whose establishment helps us to compute the chronology of the Gospels.[3] The valley itself is still known here as Abila; and therefore, through a characteristic confusion of names, the Moslems locate the grave of Abel on the summit of an adjoining hill. Cain, they say, was at his wits' end how to dispose of the dead body of his brother, for burial was of course unknown to him; so the murderer carried the corpse on his back many days, seeking in vain a place where he might securely conceal the evidence of his crime. At last, according to the Koran, "God sent a raven which scratched upon the ground, to show him how he might hide his brother's corpse."[4]

Across the ravine from Suk Wadi Barada we can see the remains of an ancient road hewn in the solid rock, and a ruined aqueduct which some say was built by Queen Zenobia to carry the water of the Abana across the desert to Palmyra. It is almost certain, however, that both road and aqueduct, as well as the tombs whose openings appear higher up in the cliff, were constructed in the second century by the Romans.

Ain Fijeh, the next important village, bears a peculiarly redundant name, which reminds us of German Baden-Baden. The first first word is Arabic and the second is a corruption of the Greek pege, and both mean "spring." But, after all, "Spring Spring" is not such a bad name; for there gushes from a cave in the rock such an abundant fountain that the Abana here increases threefold in volume, and mediæval Arab geographers, as well as the modern inhabitants of the mountains, are unanimous in considering this the principal source of the river. From the cold, clear spring, a small tile aqueduct has for the last few years carried drinking-water to Damascus. Unfortunately, however, only a few of the more important buildings are as yet supplied from this source, and the common people are loath to journey to the public fountains when there are all over the city so many nearer—and dirtier—streams from which to draw. "The Moslems, especially, prefer to drink water which runs in the open rather than that which is piped," said a native physician in answer to my questions as to the health of Damascus. "So, you see," he added facetiously, "my practice has not suffered appreciably since the completion of the aqueduct."

As we descend the narrow, winding valley of the Abana, it becomes more and more choked with

An old bridge over the Barada River

Cascade falling over the edge of the Hauran into the Yarmuk Valley

verdure. We now begin to understand why the Greeks called this the Chrysorrhoas or "Golden River." If we take advantage of one of the lengthy stops to step across the track and plunge our hands into its icy waters, we realize the fitness of its modern Arabic name, Baradâ—the "Cold Stream." Occasionally we still glimpse far above us grim, treeless heights; but, between the cliffs, dense thickets or closely planted orchard trees line the river-banks. Now the Abana is a roaring, foaming torrent; now it flows chill, deep and silent; but always it hurries as if it were racing with the train. This, in its turn, goes more rapidly. It twists and swings and bumps as it takes dangerously short curves at—for a Syrian train—full speed. We pass into the shadow of a beetling precipice and, beneath the thick foliage which overhangs it, the river runs black as ink. Then, suddenly, we have left the gloom of the mountains and are out in the bright sunlight which floods a boundless plain. We have crossed to the eastern edge of Syria and before us, just beyond the orchards of Damascus, lies the desert.

- ↑ This is the correct rendering of Judges 3:3.

- ↑ C. R. Conder, the eminent Palestinian archaeologist, points out that Arabic grammar necessitates our translating Jebel esh-Sheikh "Mountain of the Sheikh," and derives the appellation from the fact that in the tenth century the founder of the Druse religion took up his residence in Hermon (Hastings, Dictionary of the Bible, s. v. "Hermon"). But no one who has seen the white head of the tall, strong mountain can help thinking of Hermon as itself the proud^ reverend sheikh of the glorious tribe of Syrian peaks.

- ↑ Cf. Luke 3:1.

- ↑ Sura 5:34.