The Aborigines of Victoria/Volume 1/Chapter 1

Very different accounts have been given by voyagers and explorers relative to the color and form of the natives of Australia. Some have represented them as coal-black, like the negro, with bottle-noses, spare limbs, and ferocious countenances: others as models of symmetry, having a complexion scarcely so dark as to conceal a blush; and the greater number regard them simply as "blacks," with such conformations generally as belong to the African.

They differ in appearance in different parts of the continent, and this may account, in a measure, for the different statements made by observers. They differ from one another in stature, bulk, and color probably as much and no more than the inhabitants of Great Britain, Germany, France, and Italy differ from one another. Those that have abundance of food are tall and stout, and exhibit well-developed figures; and such as maintain a precarious existence in the arid tracts which the larger animals do not frequent are small, meagre, thin-limbed, and most unpleasing in aspect.

I sought information, during the year 1870, relative to the height, weight, and chest-measurement of the Aboriginal natives of Victoria, and I have compiled the following tables from the figures supplied by the Managers of the several Stations in the colony:—

Height, Weight, &c., of Aboriginal Natives at Coranderrk, Upper Yarra, from information furnished by Mr. John Green:—

| Name. | Age. | Height. | Girth. | Weight. | Name. | Age. | Height. | Girth. | Weight. | ||||

| Men. | years. | ft. | in. | ft. | in. | lbs. | Boys. | years. | ft. | in. | ft. | in. | lbs. |

| Tommy Banfield | 26 | 5 | 6½ | 3 | 9 | 214 | Samson | 15 | 5 | 4½ | 2 | 9 | 115 |

| Wellington | 34 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 2½ | 150 | Martin | 16 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 115 |

| Peter Hunter | 30 | 5 | 3½ | 3 | 0 | 145 | M. Bell | 16 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 115 |

| Redman | 40 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 134 | McRea | 16 | 5 | 6½ | 2 | 9 | 145 |

| Dick | 36 | 5 | 3½ | 3 | 4½ | 150 | Willie Hobson | 9 | 4 | 1½ | 2 | 1 | 59 |

| Tommy Arnot | 28 | 5 | 5½ | 2 | 11½ | 126 | Women. | ||||||

| Donald | 23 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 11½ | 125 | Eliza | 37 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 135 |

| Johnny Philips | 25 | 5 | 5½ | 2 | 11½ | 127 | Maggie | 33 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 98 |

| Avoca | 36 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 130 | Sally | 50 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 2½ | 139 |

| Harry | 40 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 127 | Borat | 36 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 10 | 108 |

| Jemmy Barker | 36 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 134 | Norah | 30 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 124 |

| Simon | 40 | 5 | 10½ | 3 | 2 | 148 | Harriett | 36 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 132 |

| Annie | — | 5 | 1 | 2 | 10½ | 110 | |||||||

Height, Weight, &c., of Aboriginal Natives at Lake Hindmarsh from information furnished by the Rev. A. Hartmann:—

| Name. | Age. | Height. | Weight. | Name. | Age. | Height. | Weight. | ||

| Blacks.—Men. | years. | ft. | in. | lbs. | Blacks.—Women. | years. | ft. | in. | lbs. |

| Phillip | 37 | 5 | 8 | 138 | Diana | 25 | 4 | 10¾ | 94 |

| Thomas | 27 | 5 | 6¾ | 134 | Betsy | 21 | 5 | 1 | 105 |

| David | 34 | 5 | 3 | 112 | |||||

| Coyle | 24 | 5 | 7 | 124 | Half-Castes. | ||||

| Henry | 24 | 5 | 5½ | 122 | Man. | ||||

| Women. | Jackson | 25 | 5 | 8¼ | 150 | ||||

| Elizabeth | 19 | 5 | 0½ | 103 | Women. | ||||

| Ida | 16 | 4 | 11½ | 108 | Rebecca | 24 | 5 | 6 | 143 |

| Susan | 27 | 4 | 11¾ | 129 | Topsy | 22 | 5 | 2 | 104 |

Height, Weight, &c., of Aboriginal Natives at Lake Condah from information furnished by Mr. Joseph Shaw:—

| Name. | Age. | Height. | Weight. | Name. | Age. | Height. | Weight. | ||

| Blacks.—Men. | years. | ft. | in. | lbs. | Blacks.—Women. | years. | ft. | in. | lbs. |

| Billy King | 38 | 5 | 8 | 164 | Susanna | 32 | 5 | 1 | 112 |

| John Green | 33 | 5 | 6 | 138 | Mary Robinson | 28 | 5 | 0 | 100 |

| Billy Govatt | 32 | 5 | 5 | 138 | Mary Gorrie | 35 | 4 | 10 | 78 |

| John Sutton | 34 | 5 | 5½ | 133 | Old Kitty | 62 | 4 | 11 | 104 |

| Jemmy Robinson | 35 | 5 | 1 | 118 | Old Fat Corner | 60 | 5 | 0 | 115 |

| Billy Wilson | 37 | 5 | 4 | 134 | |||||

| Jemmy Field | 56 | 5 | 3 | 120 | |||||

| Billy Gorrie | 40 | 5 | 8 | 148 | Half-castes. | ||||

| Timothy | 30 | 5 | 2 | 114 | Man. | ||||

| Old Jack | 60 | 5 | 3 | 120 | Johnnie Dutton | 23 | 6 | 0 | 170 |

| Women. | Women. | ||||||||

| Mrs. Wilson | 30 | 5 | 0 | 100 | Hannah King | 26 | 5 | 5 | 193 |

| Lucy Sutton | 32 | 5 | 1 | 100 | Ellen Mullet | 22 | 5 | 2½ | 120 |

Height, Weight, &c., of Aboriginal Natives at Lake Wellington, in Gippsland, from information furnished by the Rev. F. A. Hagenauer:—

| Name. | Age. | Height. | Weight. | Name. | Age. | Height. | Weight. | ||

| Blacks.—Men. | years. | ft. | in. | lbs. | Blacks.—Women. | years. | ft. | in. | lbs. |

| Charles Foster | 28 | 6 | 1 | 166 | Jenny | 25 | 5 | 1 | 131 |

| Nathaniel Pepper | 31 | 5 | 6½ | 128 | Louise | 19 | 5 | 4 | 142 |

| Bobby Brown | 26 | 5 | 4¾ | 157 | Caroline | 17 | 5 | 2½ | 148 |

| James Clark | 28 | 5 | 4 | 140 | Ada Clark | 16 | 4 | 11 | 102 |

| Harry Stephen | 16 | 5 | 5 | 138 | Bessy | 20 | 4 | 11½ | 133 |

| Ngarry | 53 | 5 | 6 | 130 | Rhoda | 21 | 5 | 0 | 112 |

| Donald | 20 | 5 | 8½ | 145 | |||||

Height, Weight, &c., of Aboriginal Natives at Lake Tyers, in Gippsland, from information furnished by the Rev. John Bulmer:—

| Name. | Age. | Height. | Weight. | |

| Blacks.–Men. | years. | ft. | in. | lbs. |

| Tommy Johnson (young man) | about 17 | 5 | 6½ | 134 |

| Benjamin Jennings (young man) | about 30 | 5 | 6½ | 148 |

| William McDougall (young man) | about 28 | 5 | 2 | 141 |

| Toby (young man) | 28 | 5 | 5¾ | 125 |

| Charley Buchanan | 36 | 5 | 3¾ | 119 |

| McLeod | 35 | 5 | 3 | 130 |

| Charley Anderson | 19 | 5 | 7½ | 143 |

| William Flanner | 35 | 5 | 3 | 133 |

| Dick Cooper | 30 | 5 | 8½ | 145 |

| King Charley | 35 | 5 | 9¼ | 144 |

| Billy the Bull | 30 | 5 | 8¾ | 178 |

| Dan (old man) | 50 | 5 | 5 | 130 |

| Billy Jumbuck (old man) | 50 | 5 | 5 | 130 |

| Jackey Jackey | 48 | 5 | 7¾ | 159 |

| Charley Blair (young man) | 28 | 5 | 7 | 120 |

It appears, from these tables, that the average height of forty-nine adult male blacks is 5 ft. 5¾ in.—the greatest height being 6 ft. 1 in., and the least 5 ft. 1 in.; and that the average weight is 137⅔ lbs. nearly—the greatest weight being 214 lbs., and the least 112 lbs.

The average height of twenty-five adult black females is 5 ft.—the greatest being 5 ft. 4 in., and the least 4 ft. 9 in. The average weight of the women is 114½ lbs. (nearly)—the greatest being 148 lbs., and the least 78 lbs.

The half-castes appear to great advantage, as compared with the natives of pure blood. Though the records relate only to a small number, they are nevertheless highly suggestive. The average height of the half-caste men is 5 ft. 10⅛ in., and the average weight 160 lbs.; and the average height of the women is 5 ft. 3¾ in., and the average weight 140 lbs.

These results are in accordance with what one sees in a large mixed assemblage of blacks and half-castes. The latter are invariably larger, better formed, and more fully developed than the blacks; and some of the boys—showing but little of the blood of the mother—are better formed and more pleasing in appearance than many children born of white parents. When they grow up, however, they usually become coarse and heavy.

It will be noted also, on examining the tables, that the height and weight of the men and women in Gippsland are greater than the averages; that the height and weight of the men at Coranderrk are considerably above the averages; and that the women at that station, though of average stature, are much heavier than the women of the western parts of the colony. The natives at Coranderrk, however, having been brought from all parts of Victoria, are not representative of any particular tribes, as are those at Lake Hindmarsh, Lake Condah, and Gippsland.

Dr. Strutt gives the following Measurements of Natives of the River Murray at Echuca:—

| Name. | Weight. | Height. | Measures round the chest. | |||

| stone | lbs. | ft. | in. | ft. | in. | |

| Daniel | 10 | 0 | 5 | 7½ | 2 | 10 |

| Johnny Johnny | 10 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 10 |

| Billy | 8 | 0 | 5 | 4½ | 2 | 8 |

| Jack | 9 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 8½ |

| Larry | 10 | 10 | 5 | 8½ | 3 | 0¾ |

| Billy Toole | 10 | 0 | 5 | 4½ | 3 | 0½ |

| Murray | 10 | 0 | 5 | 6½ | 2 | 11½ |

| King John | 11 | 12 | 5 | 9¾ | 3 | 1 |

| Flora | 9 | 0 | 4 | 10½ | 3 | 2 |

He adds that "No other woman could be persuaded to be weighed or measured;" and that "they are a well-proportioned race."[1]

It is impracticable to obtain complete measurements of the bodies of the natives of Victoria. They are now clothed—and having regard to the circumstances under which they are living, it has been deemed unadvisable, even in the interests of science, to prosecute investigations which might raise in their minds feelings of disgust. I have therefore no very valuable information to give in regard to this part of the subject. Some measurements have been made from photographs of wild blacks with the following results:—

| — | Man. | Man. | Man. | Woman. | Woman. |

| Ground of calf to leg (thickest part) | 8¾ | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Ground to centre of cap of knee | 14 | 13¾ | 13¾ | 14 | 14 |

| Ground to fork | 22½ | 22 | * | 22½ | 23 |

| Ground to umbilicus | 31 | 31 | 30½ | 30 | * |

| Ground to chin | 43 | 41 | * | 42¼ | 42½ |

| Ground to tips of fingers (the hand being placed against the thigh) | * | * | * | 17 | 18 |

| Length of arm from point of shoulder to elbow. | 11½ | 11 | 10¼ | 9½ | 9 |

| Length of arm from elbow to tips of fingers | 14½ | 14 | 13 | 14 | 14 |

In the spaces marked * measurements were not possible.

The body in each case is supposed to be divided into fifty parts, measuring from the ground to the vertex, and the proportions are represented by the figures.

Though the utmost care was taken in ascertaining the proportions of the several parts of the frame, and though the photographs were excellent, and the positions well chosen, these measurements cannot be regarded as strictly accurate.

Measurements made in the same manner of two Europeans, one an adult male and the other a young man, give the figures following, namely:—

| — | Adult. | Young man. |

| Ground to calf of leg (thickest part) | 10¼ | 10 |

| Ground to centre of cap of knee | 13 | 14½ |

| Ground to fork | 21½ | 25¾ |

| Ground to umbilicus | 29½ | 30¾ |

| Ground to chin | 43½ | 43¾ |

| Ground to tips of fingers (the hand being placed against the thigh) | 19½ | 19 |

| Length of arm from point of shoulder to elbow | 10¼ | 10 |

| Length of arm from elbow to tips of fingers | 13 | 13 |

These measurements, few as they are, seem to show that the arms and legs of the male blacks are longer than those of Europeans. Collins relates that Capt. Paterson found up the Hawkesbury natives who appeared to him to have longer legs and arms than those of the natives of Port Jackson and the coast, due, it was suggested, to their being obliged from infancy, in order to gain a living, to climb trees, hanging by their arms and resting on their feet at the utmost stretch of the body.[2]

Mr. William Skene gives the following measurements of three blacks living at Portland Bay, who, he thinks, are rather under the sizes of some tribes[3]:—

| — | Jemmy. | Tommy. | Billy. |

| Age | 25 to 30 years | 50 years (about) | 25 years (about) |

| Height | 5 ft. 7¼ in. | 5ft. 6 in. | 5ft. 3 in. |

| Rouud tbe sboulders | 44 in. | 41 in. | * |

| From shoulder to palm of hand | 33 in. | 31 in. | 29½ in. |

| Leg | 32 in. | 28½ in. | 29 in. |

| Girth of thigh (above trousers) | 19 in. | 19 in. | 20 in. |

| Girth of waist | 32 in. | 30½ in. | 33½ in. |

Color, Hair, etc.

The color of the natives of Victoria is a chocolate-brown, in some nearly answering to No. 41 of M. Broca's color-types, in others more nearly approaching No. 42; the eyes are very dark-brown (almost black), corresponding nearly to No. 1 in M. Broca's types; the "white of the eye" is in all cases yellowish, the tint being deeper in some than in others; the hair of the head is so deep a brown as to appear in many lights jet-black, and jet-black in some it is. The beard is black. The hair of the head is usually abundant, and waved or in large curls. The beard is full, and generally crisp. The brown color of the hair of the head is most often seen in that of the women and girls. The hair growing on the back of the boys and girls is very fine and soft, and in color brown (not very dark).

Mr. Cosmo Newbery, B.Sc., has made a number of careful microscopic examinations of seven samples of hair from the following individuals, namely:—Half-caste woman, "Ralla" (head); half-caste man, "Parker" (head); black man, "Wonga" (head); black woman, "Maria" (head); black girl (head); boy, aged seven years (back); girl, aged seven years (back); and he reports that, after having compared them with a number of samples taken from Europeans, he has failed to detect any special characters.

The bodies of some of the men and boys are said to be entirely covered or almost entirely covered with short soft hair.

Dr. Strutt, speaking of the natives of Echuca, says that the complexion is "a dark chocolate-brown, approaching to black; hair, black, rather coarse and curling, not woolly; black eyes; thick nose, rather rounded; lips rather thick, but not projecting."[4]

The late Dr. Ludwig Becker, an artist and a man of science, thus writes:—"The prevailing complexion is a chocolate-brown. Hair, jet-black, and when combed and oiled, falls in beautiful ringlets down the cheeks and neck. Beard, black, strong, curly; eyes, deep-brown, black, the white of a light-yellowish hue."

The hair of the head, in both men and women, is coarser and stronger than the hair of Europeans, and it is usually far more abundant.

I have never seen in any native of Victoria that peculiar bluish or leaden tint which in some lights appears so distinctly in the complexion of the Maori of New Zealand and the lighter-colored races of Polynesia. The eye and the skin of the Australian exhibit invariably warm tints, however deep may be the color.

Some children of full-blooded blacks are nearly of the same color as European children when born, and all of them are generally light-red.[5] As regards form, they do not differ very much from children of other races. But when they arrive at the age of two, four, six, or eight years, they are generally very dark, and in form differ much from Europeans. The head is generally well shaped and well placed, the eyes are large, and the body is well formed, though the limbs are long, and in some individuals thin, and the face is not agreeable. The under-jaw is large, and the lips are heavy and hanging. Some children are prognathous to such a degree as to present a profile anything but pleasing. The cheeks of both males and females are hairy in the places where the beard grows in man; and the neck and in some the back are covered with short hair, always thickest in those parts which in most Europeans are shown obscurely by streaks of hair coming down the neck from the head, and following the line of the vertebræ. The arms and hands exhibit a thin covering of coarse hair.

Little boys of five and six years of age show sometimes as much hair on the cheeks as a European of seventeen or eighteen, but the hair is not crisp and curly as the hair of a beard generally is, but straight and clinging closely to the face. It is of the same character as the hair on the arms or hands, but thicker and closer.[6] I am not acquainted with a single case of albinism amongst the natives of Australia.

Odour.

There is little doubt that there is a peculiar odour attached to the persons of the natives even when they are clean in their habits. Some have a most offensive odour, due to their want of cleanliness and to their sleeping in their clothes. It is a different odour from that of Europeans of filthy habits, and as strong, or perhaps stronger. Dr. Strutt says that several of the natives have no peculiar odour when well washed and clean; others, however, in hot weather have a very perceptible odour.

The late Dr. Ludwig Becker noticed a peculiar odour, not depending on want of cleanliness, and resembling that of the negro, but not so strong. It appeared to him "as if phosphorus was set free during the process of perspiration. It is very likely this odour which enables the horses to discover the proximity of Aborigines, and thus saving many times the members of exploring expeditions from being surprised. Leichhardt, Gregory, and others describe sufficiently the mode in which the horse shows its uneasiness."[7]

Cattle and dogs, as well as horses, exhibit alarm when they are approached by a black for the first time, and when his vicinity could be known only from the odour.

Senses.

The sight and hearing of the natives are excellent, but it is questionable whether as regards touch, taste, and smell they are the equals of Europeans. Short-sight is not known amongst the people of Victoria.

Many of the natives are skilful trackers, and their services are frequently required by the police, who speak highly of their quickness and intelligence. The native trackers have on many occasions rendered important services to the Government, and when any one is lost in the bush the whites rely with the utmost confidence on the sagacity and skill of the "black-tracker."

Capt. Grey relates how his watch was recovered by a native. It had fallen from his pocket when galloping through the bush. "The ground we had passed over," says Grey, "was badly suited for the purpose of tracking, and the scrub was thick; nevertheless, to my delight and surprise, within the period of half an hour my watch was restored to my pocket. This feat of Kaiber's surpassed anything of the sort I had previously seen performed by the natives."[8]

"Their sight," says Collins, "is peculiarly fine; indeed their existence very often depends upon the accuracy of it; for a short-sighted man (a misfortune unknown among them, and not yet introduced by fashion, nor relieved by the use of a glass) would never be able to defend himself from their spears, which are thrown with amazing force and velocity."[9]

Physical Powers.

Many of the natives have great strength in the arms and shoulders, and the manner in which they throw the spear, the boomerang, and the woit-woit shows that they can exert their strength to the best advantage. But their hands are small, and, as a rule, they are not capable of performing such heavy labors as a white man. They are soon fatigued; and the mind, in sympathy with the body, disinclines them to continuous labor of any kind.

In their natural state they were accustomed to the use of their weapons only; hunting and fighting were their employments. The women carried the burdens, and did the most of the work that was to be done.

They are good walkers, they can run very fast, and jump to an amazing height; but when they have to travel day after day, they soon show that in endurance they are not the equals of Europeans. This, at any rate, is the impression left on the minds of many who have had to travel on foot with the natives. No doubt a strong and healthy native would exhibit superiority to any untrained European, both as regards speed and endurance; but a strong white man, accustomed to walk fast and far, would soon outstrip the native.

They ride well and sit often gracefully, and manage a horse with temper and judgment; but it has been remarked by those accustomed to ride with the natives that they will never put a horse at a fence. Whether they are deficient in courage or whether it is because they find no pleasure in the exercise is not known.

Using the Feet and Toes.

The natives use their toes in dragging their spears, when they wish to conceal their weapons, and they use them also in ascending trees, in such a manner as to suggest that the joints of the great toe are more pliable and the muscles more under the command of the will than is the case with Europeans. The women also make use of the great toe of the right foot when they are twining rushes for their baskets, and it is believed there is some reason to suppose that the great toe is opposable.[10]

They use their feet, too, in many ways. A man will draw up his foot and use it as a rest when he is shaping a piece of wood with his hatchet. FIG. 1.

Boom-bul-wa and Quar-tan-grook, his wife.

To face page 9, vol. I.

Races.

Two natives of Gippsland—Boom-bul-wa and Quar-tan-grook, his wife (Fig. 1), are characteristic types of the natives of the eastern parts of Victoria. Boom-bul-wa was rather above the average height, and was a strong well-made man. Both the man and woman were full-blooded blacks.

The portraits shown in Fig. 2 are those of natives of different parts of the colony. The woman in mourning, and the woman and child, are natives of

FIG. 2.

the Western district (Hopkins River); the girl with the raised scars on her breast and shoulders, the boy to the left of the central figure, and the man and woman immediately below, belong to the river Yarra Yarra. The last-named— Wonga, the principal man of the Yarra tribe, and his wife—are two well-known natives. Wonga has a mild disposition, and is always gentle and courteous. He is a good speaker, and has much influence with his people. The man to the right of the central figure is Nathaniel, generally regarded as highly intelligent. He was educated at the Lake Hindmarsh Station. The man holding a spear is Whyate, a black from the western coast. He is of a type that is by no means common. The central figure shows a native in ordinary attire.

|

| FIG. 3. |

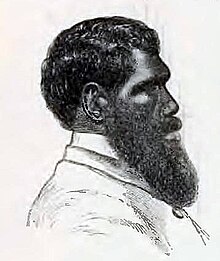

The likeness in profile (Fig. 3) is that of a full-blooded black of the ordinary type. The form and expression are strongly characteristic of the natives of the south. The portrait of a woman (Fig. 4) shows the more marked features that are commonly found amongst the females of the Yarra. These portraits exhibit with sufficient distinctness the general character of the features of the natives of Victoria. The eyebrows are broad and prominent, over-hanging deep-set and not very small eyes; the head narrows rapidly towards the vertex; the mouth is large, and arched, as if the corners were purposely drawn down; the lips are full. The under-jaw of the males is, in many instances, massive and square; in others, owing to the size and shape of the mouth and teeth, it is retreating. The nose is depressed at the upper part, and wide at the base, and in some the wings are elevated; the space between the nose and the mouth is great, and the alveolar process is much developed. The cheek-bones are high. The teeth are large and regular, and when set, meet closely, the cusps being usually worn off, owing to their modes of cookery and feeding. In many the neck is short and pretty thick, but thin necks are not uncommon.

|

| FIG. 4. |

When in repose, the expression of the countenance is not pleasing. It is rather sullen than melancholy. But when anything occurs to arouse the curiosity of the native, his face lights up at once, and the sour, morose expression gives place to one that is far from disagreeable. He can indicate by his features discontent, dislike, hatred, affection, satisfaction, curiosity, and appreciation of humour, with unmistakable effect. In like manner he can show by his gait and his gestures fear, respect, obedience, courage, defiance, and contempt. Those who have lived long amongst the natives and are acquainted with their habits are not readier than those who see them for the first time in comprehending what is expressed by their attitudes.

The natives of Brisbane (Queensland) differ a good deal in appearance. The accompanying drawings (Figs. 5 and 6) represent the ordinary Australian type. That of the man was selected because of the extraordinary character of the scars on his back.

|

|

| FIG. 5. | FIG. 6. |

I have seen some blacks from the north, and I never could detect any very striking difference in their aspect. Generally, they looked like Victorian blacks; but amongst the large number of photographs I have received of natives of the north-east coast, it is easy to put aside many that certainly bear no very close resemblance to the ordinary Australian native. The hair of some is frizzled, and the beard is scanty, appearing only as a small moustache, and a slight frizzled tuft on the chin. The eyebrows do not project very much, the nose is nearly straight, and not very broad at the base, and the brow is rounder and smoother than that commonly seen. The hair of some of the girls falls in long, very small ringlets; but the faces of nearly all the females are of the usual Australian type. The marked differences of feature appear only amongst the males.

It was intended that portraits showing the types of natives of all the islands adjacent to Australia, and those of the negro, and the natives of India, should have been given here, in order that the reader might have compared them with those of the Australians; but owing to the haste with which this volume has been completed, this part of my design is unfulfilled. A few portraits accompany those of the Australians; and as these, as well as the latter, have been carefully drawn from excellent photographs, it is hoped that these fresh materials for a proper study of the races they represent will be appreciated by ethnologists.

The Australian natives have been harshly dealt with in nearly all the works that treat of ethnology. In many their faces are made to appear as like those of baboons as possible; and though it must be confessed that, as a rule, neither the men nor the women have pleasing countenances, they are as thoroughly human in their features and expression as the natives of Great Britain.

At first they appear to resemble each other very much; and a stranger, even after seeing them frequently, is often unable to distinguish one man from another.

Though unlike the Australian natives in many respects, the Tasmanians still exhibit in their countenances a resemblance to them; and years ago, when it would have been possible to have made a selection from a large number, it is probable that some individuals could have been found not differing at all in features from the rather lighter colored natives of Victoria. William Lanny, whose portrait is given here (Fig. 7), and who is described as the last of the Tasmanians, is not unlike many natives that are seen in the eastern parts of Australia. The eyebrows do not project much, the head is round, the hair is frizzled, and, but for the full beard, he might be mistaken for a native of the north-eastern coast.

FIG. 7.

At the time the photograph from which the wood-cut is drawn was taken, William Lanny was 26 years of age. He was a native of the Coal River tribe.

There are marked differences of form in the head and features of the two races in New Zealand—the Maori, and the Pokerekahu or black Kumara.[11] Hale, the ethnologist who accompanied the United States Exploring Expedition in 1838-42, seemed, however, to disbelieve in this distinction, regarding the yellow Polynesians and the so-called Papuans as the same; the one class being idle and luxurious, and the other workers, half-starved and ill-clad. That there is a striking difference in appearance is admitted; and though it is true that in many of the islands in the South Seas different modes of life largely affect the appearance of the natives—the chiefs being tall, well-made men, of a light complexion, and the workers smaller, thinner, and dark in color—it is conclusively proved by the Rev. Richard Taylor that the Melanesian preceded the Maori in the occupation of New Zealand.

The accompanying portraits of New Zealanders have been selected with the view of affording some information on this point. Fig. 8 represents a native chief, Tomati Hapimana Wharehinaki, whose family name was, he said, Tapuika, and that of the land he once owned, Maketu. When I saw him, in November 1870, he was about fifty-seven years of age. He is, I believe, now dead. His head was small, his forehead narrow, his eyebrows rather prominent, but, on looking at the full face, not coarse; his skin light-brown, and his eyes a not very dark-brown. His hair was soft, dry, and black in color. He was very talkative, and used odd little gestures to eke out his meaning. Though he had been an actor in a theatre, and had lived long with Englishmen, he spoke the English language with diffieulty. Many words he could not pronounce at all; and though belonging to the better class of his people, he appeared to me to be far inferior to the Australian in the power of acquiring language, and in intelligence generally. In talking to a clever Australian native one feels that one is speaking to a person who has all the faculties (though undeveloped) of a European, and he is generally quiet and dignified in his manner; but the Polynesian, the Malay, and some others, have always seemed to me to belong to raccs having little or nothing in common with the European.

|

|

| FIG. 8. | FIG. 9. |

Tomati Hapimana's skin showed in some lights the peculiar leaden-blue tint so characteristic of the Malayo-Polynesians.

|

|

| FIG. 10. | FIG. 11. |

The portrait of a man with a feather in his hair (Fig. 9) was sent to me as a specimen of the Indo-European type of the Maori; Fig. 10, as one exhibiting Mongolian features; and Fig. 11, as a man of the Papuan type.

The Mongolian features are better shown in the photographs of the women, some of whom are much like the Chinese females. The eyes are slightly oblique, but the cheek-bones are not high; and in some examples the face is oval and the contour almost beautiful.

|

| FIG. 12. |

The portrait (Fig. 12) is that of a son of a chief of the Island of Mauti or Mauke—one of the Cook or Hervey's Group. In appearance generally he resembles the Maori of New Zealand, but he is not tattooed. His face, when animated, exhibited a culture, intelligence, and refinement not usually seen, I believe, amongst the Maories. This young man, who wrote his name Tomanu, came on a visit to Melbourne. He could speak but little English—only a few words—but he had evidently been well educated by the Missionaries. The skin of his face was rough and coarse, his complexion a deep yellowish-olive, his eyes horizontal and dark-brown, the "whites" pretty clear; his hair black, with here and there a white hair; he had rather scanty indications of a beard, and a retreating forehead, but a not unshapely head. His neck was strong, and he was a tall, large, rather heavy man. He may be regarded as a fine specimen of the Malayo-Polynesian. It is said that in the islands where he lives the lower classes are very dark, and inferior in stature and in appearance to the chiefs. He spoke with a slight lisp.

He gave me a few words of his native tongue. They are as follow:—

| Head | Mowk-ke. |

| Eyes | M'atta. |

| Nose | Put-i-u. |

| Mouth | Vah-vah. |

| Teeth | Ne-o. |

| Chin | Tangla. |

| Beard | Oo-roo-roo. |

| Tongue | Lillah. |

| Hand | Dimang. |

| Feet | Vah-veer. |

| Fingers | Mong-ah Mong-ah. |

| Nails of fingers | Mikeah. |

I could not ascertain whether or not the numerals in his language went beyond five. He gave me the following only:—

| One | Kotti. |

| Two | Karoo-ah. |

| Three | Kaderooh. |

| Four | Ka-ah. |

| Five | Kerimang. |

One of the words for head in the language of the New Zealanders is Makawe; the word for eye in the dialect of De Peyster's Islands, the Marquesas, and Cocos Islands, is mata; that for nose in the Marquesas and in the Kanaka dialect of the Sandwich Islands is ihu; and at Satawal it is poiti. Mouth in the Marquesas is fa fa, and tooth is niho; and in the Kanaka of the Sandwich Island the tongue is lelo, and the foot is vae.

In the dialects of Polynesia and Micronesia there are some words that have the same sound as words in the language of the Australians; but the meanings attached to them are not always the same. Such coincidences would point to conclusions of great importance if supported by other circumstances.

|

| FIG. 13. |

Rather a favorable specimen of the Chinese, who are numerous in Victoria, is represented in Fig. 13. His head greatly contrasts that of the Australian. The smooth rounded contours and the arched brow are characteristic of the race. Many of them have well-developed foreheads, but the oblique eyes, the laterally projecting cheek-bones, and the form and small size of the nose, make no very pleasing picture in the sight of a European. Very few have beards, and some show only a few scattered hairs on the upper lip and chin.

The Chinese in Melbourne—I speak only of the laboring classes—are fond of gambling and indulge in opium smoking; but they are otherwise sober in their habits and very industrious. They will carry very heavy burdens all through the hottest day of summer without appearing to be fatigued. They are good traders and most excellent gardeners. Many are married to European women, and their children exhibit, I think, invariably a stronger likeness to the father than to the mother.

It is not known from what part of China this person whose portrait is given here came.

The descriptions of the natives of Australia, as given by various observers, are instructive.

Mr. Stanbridge thus describes them:—"Unlike the Aborigines of Tasmania, whose color is black, with black woolly hair, those of Victoria have complexions of various shades of dark olive-brown, and in some instances so light that a tinge of red is perceptible in the cheeks of the young, with slightly curly black hair; but there are isolated cases of woolly hair amongst the men and dark-brown hair amongst the women. This difference in the color of the skin appears distinctly marked in the half-breeds, the Australian being invariably of a brown or gipsy tinge, while the only Tasmanian known to the writer was of a black or negro hue. They are straight-limbed, square-shouldered, slightly but compactly made; occasionally an individual of herculean proportions is met with. There are none amongst them who are deformed, except those who have become so by accident. The men vary in stature from five to, in a few cases, upwards of six feet. They have thick beards, high cheek-bones, rather large black eyes, protruding eyebrows, which make the forehead appear to recede more than it really does, as high foreheads are not uncommon amongst them; thickish noses, which are sometimes straight and sometimes curved upwards; very large mouths and teeth; the size of the latter and the squareness of the jaw are probably caused by continually tearing food with the teeth, as young children have not that squareness of jaw, neither have boys who have lived almost entirely with white people. Their mode of whistling, which consists in drawing the lower lip with the finger and thumb tightly on one side, has its influence, no doubt, on the size of the lips. The men of the Coorong, who subsist almost wholly upon fish, have much smaller mouths and thinner lips; their eyebrows also are not so heavy. In appearance they much resemble the New Zealanders."[12]

Dr. Strutt says of the natives of the River Murray:—"The face is generally round, rather broad, chin round and well formed, mouth large."[13]

Mr. Taplin writes thus:—"There is a remarkable difference in color and cast of features. … Some natives have light complexions, straight hair, and a Malay countenance; while others have curly hair, are very black, and have the features of the Papuan or Melanesian. It is therefore probable that there are two races of Aborigines; and, most likely, while some tribes are purely of one race or the other, there are tribes consisting of a mixture of both races."[14]

Mr. Carl Wilhelmi observes that the "striking peculiarities in the appearance of their body are their miserably thin arms and legs, wide mouths, hollow, deep-sunken eyes, and flat noses; if the latter are not naturally so formed, they make them so by forcing a bone, a piece of wood, or anything else, through the sides of the nose, which causes them to stretch. They generally have a well-arched front, broad shoulders, and a particularly high chest. The men possess a great deal of natural grace in the carriage of their body; their gait is easy and erect, their gestures are natural under all circumstances—in their dances, their fights, and while speaking; and they certainly surpass the European in ease and rapidity of their movements. With respect to the women we cannot speak so favorably by a great deal; their bodies are generally disfigured by exceedingly thin arms and legs, large bellies, and low hanging breasts, a condition sufficiently accounted for by their early marriages, their insufficient nourishment, their carrying of heavy burdens, and the length of time they suckle their children, for it is by no means uncommon for children to take the breast for three or four years, or even longer."[15] Mr. Wilhelmi adds, that there are considerable varieties not only of countenances and forms of body, but also of colors and skins. The skin of the tribes of the north is dark and dry in appearance, and that of the people of the south approaches a copper-color.

The Rev. Mr. Schürmann believes that the best fed and most robust natives are of the lighter colors.

Capt. Grey, writing of the natives of North-Western Australia, says:—"They closely resemble the other Australian tribes, with which I have since become pretty intimately acquainted; whilst in their form and appearance there is a striking difference. They are in general very tall and robust, and exhibit in their legs and arms a fine, full development of muscle, which is unknown to the southern races. … A remarkable circumstance is the presence amongst them of a race, to appearance totally different, and almost white, who seem to exercise no small influence over the rest. … I saw but three men of this fair race myself, and thought they closely resembled Malays; some of my men observed a fourth." Grey, quoting Usberne, refers to the appearance of the people of Roebuck Bay:—"They were about five feet six inches to five feet nine in height, broad shoulders, with large heads and overhanging brows. … Their legs were long and very slight. … There was an exception in the youngest, who appeared of an entirely different race; his skin was a copper-color, whilst the others were black; his head was not so large and more rounded; the overhanging brow was lost; the shoulders more of a European turn, and the body and legs much better proportioned; in fact, he might be considered a well-made man at our standard of figure."[16]

Capt. Stokes gives the following account of the people of the north-west coast:—"The natives seen upon this coast during our cruise, within the limits of Roebuck Bay to the south and Port George the Fourth to the north, an extent of more than two hundred miles, with the exception that I shall presently notice, agreed in having a common character of form, feature, hair, and physiognomy, which I may thus describe. The average height of the males may be taken to be from five feet five inches to five feet nine inches, though, upon one occasion, I saw one who exceeded this height by an inch. They are almost black; in fact, for ordinary description, that word, unqualified by the adverb, serves the purpose best. Their limbs are spare and light, but the muscle is finely developed in the superior joint of the arm, which is probably owing to their constant use of it in throwing the spear. … Their hair is always dark, sometimes straight and sometimes curled, and not unfrequently tied up behind; but we saw no instance of a negro or woolly head among them. They wear the beard upon the chin, but not upon the upper lip, and allow it to grow to such a length as enables them to champ and chew it when excited by rage, an action which they accompany with spitting it out against the object of their indignation or contempt. They have very overhanging brows and retreating foreheads, large noses, full lips, and wide mouths."[17]

The natives of King George's Sound are thus described by Péron:—"Ces hommes sont grands, maigres et très-agiles; ils ont les cheveux longs, les sourcils noirs, le nez court, épaté et renfoncé à sa naissance, les yeux caves, la bouche grande, les lèvres saillantes, les dents très belles et très blanches. L'intérieur de leur bouche paroissoit noir comme l'extérieur de leur corps. Les trois plus âgés d'entre eux qui pouvoient avoir de quarante à cinquante ans, portoient une grande barbe noire; ils avoient les dents comme limées, et la cloison des narines percée; leur cheveux étoient taillés en rond et naturellement bouclés. Les deux autres que nous jugeâmes être âgés de seize à dix-huit ans, n'offroient aucune espèce de tatouage; leur longue chevelure étoit réunie en un chignon poudré, d'une terre rouge dont les vieux avoient le corps frotté."[18]

Collins observed in New South Wales natives as black as the African negro, others of a copper or Malay color. Black hair was general, but some had hair of a reddish cast.[19]

Major Mitchell saw in some places "fine-looking men." Some of the men of the Bungan tribe had straight brown hair, others Asiatic features, much resembling Hindoos, with a sort of woolly hair. The natives of the Darling, however, were not pleasing. "The expression of their countenances," he says, "was sometimes so hideous, that after such interviews I have found comfort in contemplating the honest faces of the horses and sheep; and even in the scowl of the patient ox I have imagined an expression of dignity, when he may have pricked up his ears, and turned his horns towards these wild specimens of the 'lords of the creation.'"[20]

Lieut.-Col. Mundy found some well-made men amongst the natives of New South Wales. One man—the chief of a tribe, the only old man belonging to it—is thus described:—"He was of much superior stature to the others, full six feet two inches in height, and weighing fifteen stone. Although apparently approaching threescore years, and somewhat too far gone to flesh, the strength of 'the old Bull,' for that was his name, must still have been prodigious. His proportions were remarkably fine; the development of the pectoral muscles and the depth of chest were greater than I had ever seen in individuals of the many naked nations through which I have travelled. A spear laid across the top of his breast as he stood up, remained there as on a shelf. Although ugly, according to European appreciation, the countenance of the Australian is not always unpleasing. Some of the young men I thought rather well-looking, having large and long eyes with thick lashes, and a pleasant, frank smile. Their hair I take to be naturally fine and long, but from dirt, neglect, and grease, every man's head is like a huge black mop. Their beards are unusually black and bushy. … The gait of the Australian is peculiarly manly and graceful; his head thrown back, his step firm; in form and carriage at least he looks creation's lord—

'erect and tall,

Godlike erect, in native honor clad.'

In the action and 'station' of the black there is none of the slouch, the stoop, the tottering shamble, incident all upon the straps, the braces, the high heels, and pinched toes of the patrician, and the clouted soles of the clodpole white man."[21]

Many of the natives of the eastern seaboard, like those of the Murray in Victoria, are remarkably stout and strong. Mr. Hodgkinson found a fine specimen on the Bellingen, in Queensland:—"One man in particular had been pre-eminently remarkable (in outrages on whites) from his tallness and herculean proportions; the sawyers up the Nambucca had distinguished him by the name of 'Cobbaun (big) Bellingen Jack.' I never saw a finer specimen of the Australian Aborigines than this fellow; the symmetry of his limbs was faultless, and he would have made a splendid living model for the students of the Royal Academy. The haughty and dignified air of his strongly-marked and not unhandsome countenance, the boldly-developed muscles, the broad shoulders, and especially the great depth of his chest, reminded me of some antique torso."[22]

Jardine gives no very flattering account of the natives of Cape York. "The only distinction," he says, "that I can perceive, is that they appear to be in a lower state of degradation, mentally and physically, than any of the Australian tribes which I have seen. Tall, well-made men are occasionally seen, but these almost invariably show decided traces of a Papuan or New Guinea origin, being easily distinguished by the 'thrum' like appearance of the hair, which is of a somewhat reddish tinge, occasioned, no doubt, by constant exposure to the sun and weather. The color of their skin is also much lighter, in some individuals approaching almost to a copper-color. The true Australian Aborigines are perfectly black, with, generally, woolly heads of hair; I have, however, observed some with straight hair and features prominent, and of a strong Jewish cast."[23]

Macgillivray says that the Australians of Cape York differ in no respect from those of other parts of the continent; but they do not, it appears, strike out the upper incisors, nor do they practise circumcision or any similar rite. Amongst the Aborigines of Port Essington he observed no striking peculiarity. The septum of the nose is invariably perforated, and the right central incisor—rarely the left—is knocked out during childhood. Both sexes are more or less ornamented with large raised cicatrices, on the shoulders and across the chest, on the abdomen and buttocks, and outside of the thighs. They wear no clothing; and their ornaments consist chiefly of wristlets, made of the fibres of a plant, and armlets of the same, wound round with cordage. They have necklaces formed of fragments of reed strung on a thread, or of cordage, passing under the arms and crossed over the back. Girdles of finely-twisted human hair are occasionally worn by both sexes. The men sometimes add a tassel of the hair of the opossum or flying squirrel suspended in front. A piece of stick or bone, thrust into the perforation in the nose, completes the costume. They paint themselves with red, yellow, white, and black, in different styles, appropriate to dancing, fighting, or mourning.

Speaking of the Papuans, which Macgillivray states includes, in his work, merely the woolly or frizzled haired inhabitants of the Louisiade, south-east coast of New Guinea, and the islands of Torres Strait, he says:—"They appear to me to be resolvable into several indistinct types, with intermediate gradations; thus occasionally we met with strongly-marked negro characteristics, but still more frequently with the Jewish cast of features, while every now and then a face presented itself which struck me as being perfectly Malayan. In general the head is narrow in front, and wide and very high behind, the face broad from the great projection and height of the cheek-bones and depression at the temples; the chin narrow in front, slightly receding, with prominent angles to the jaw; the nose more or less flattened and widened at the wings, with dilated nostrils, a broad, slightly arched and gradually rounded bridge, pulled down at the tip by the use of the nose-stick; and the mouth rather wide, with thickened lips, and incisors flattened on top as if ground down. Although the hair of the head is almost invariably woolly, and, if not cropped close or shaved, frizzled out into a mop, instances were met with in which it had no woolly tendency, but was either in short curls, or long and soft, without conveying any harsh feeling to the touch. In color, too, it varied, although usually black, and when long, pale or reddish at the tips [caused perhaps by the use of lime-water]; yet some people of both sexes were observed having it naturally of a bright-red color, but still woolly. The beard and moustache, when present, which is seldom the case, are always scanty, and there is very little scattered hair upon the body. The color of the skin varies from a light to a dark copper-color, the former being the prevailing hue; individuals of a light-yellowish brown hue are often met with, but this color of the skin is not accompanied by distinctive features. The average stature of these Papuans is less than our own, being only about five feet four inches."[24]

In what manner the natives of Australia impressed the earlier voyagers is told by Dampier:—"They have great bottle-noses, pretty full lips, and wide mouths. The two fore teeth of their upper-jaw are wanting in all of them, men and women, old and young; whether they draw them out I know not; neither have they any beards. They are long-visaged, and of a very unpleasing aspect, having no one graceful feature in their faces. Their hair is black, short, and curled, like that of the negroes, and not long and lank like the common Indians. The color of their skins, both of their faces and the rest of their body, is coal-black, like that of the negroes of Guinea."[25]

The French who accompanied La Perouse said, after visiting the coast of New South Wales, that in their whole voyage they nowhere found so poor a country nor such miserable people; and yet how rich is the country! and how interesting are the natives that once peopled it! Until the white man invaded their shores they were happy.

Half-castes.

Many of the half-castes in Victoria present peculiarities that are of great interest. The complexion of the females is generally a pale-brown (usually called olive), and they do not often show much red on the cheeks, though there are marked exceptions to this. The boys, on the other hand, have, as a rule, bright, clear complexions, with red cheeks; and some could not be distinguished from children of European parents. There are ordinarily patches of light-brown hair mixed with the dark-brown hair of their heads; but I have never seen any peculiarities of color in the eye. Amongst Europeans we see occasionally persons having differently colored eyes—the iris of one eye being brown, with the "white" quite clear, and that of the other deep brown-black, with the "white" flecked and streaked with bluish and brownish colors.

The young half-castes partake in their form, features, and color more of the character of the male parent than that of the Aboriginal female. It is rare to see one that strikingly resembles the black mother. The nose is usually broad, the wings of the nose are in some elevated, the mouth is large, and the lips are thick, but seldom is any one feature very strongly or coarsely marked.

A few show finely-cut features, the delicate outlines of which greatly contrast those seen amongst the natives of pure blood. Their cheek-bones do not project; the superciliary ridges are not prominent; the eyes are large, liquid, and have a soft expression; and their aspect, though somewhat foreign, is not so much so as to excite comment. They are very like the people of Southern Europe, and many would be passed by without remark in a crowd of English children.

When the half-castes attain maturity they exhibit, however, the admixture of Aboriginal blood more strongly. They become fleshy and coarse, their countenances are heavy—and some are almost repulsive.

Both the males and the females deteriorate after they have passed the age of twelve or fourteen years.

The children of a half-caste female and a white man are not to be distinguished from children of European parents. What peculiarities they may display when they arrive at maturity is not known.

Some half-castes very quickly adopt European customs, and others prefer the society of the blacks—depending on the manner in which they have been situated in their youth. A half-caste young woman from the north was living for some time in a gentleman's family in Melbourne. She was educated, had been taught music, and appeared to be more than usually intelligent.

- ↑ Report of the Select Committee of the Legislative Council, 1858-9.

- ↑ The English Colony in New South Wales, by Lieut-Col. Collins, 1804.

- ↑ Report of the Select Committee of the Legislative Council, 1858-9, p. 227.

- ↑ Report of the Select Committee of the Legislative Council, 1858-9.

- ↑ Mr. John Green says, "The baby is like a white when newly born, and pale; but in the course of a few hours it becomes dark; and in two weeks or so becomes as black as its parents."

- ↑ "Boys—full-blooded—begin to show a beard at the age of fifteen; and have a strong beard when nineteen. Half-castes show a beard at seventeen, and have not a strong beard until they are about twenty-four years old. There are several full-blooded children on the Coranderrk Station from six to ten years of age with hair on their backs one inch long and more, and as close as it can sit. There is also a third-caste white boy, about twelve years of age, with the same kind of hair on the back."–MS., Mr. John Green.

- ↑ Report of the Select Committee of the Legislative Council, 1858-9.

- ↑ North-West and Western Australia, vol. I., p. 315.

- ↑ English Colony in New South Wales, 1804, p. 359.

- ↑ "They are very expert at stealing with their toes, and while engaged in talking with any one, will, without moving, pick up the smallest thing from the ground. By means of their toes, they will also carry as many as six long spears through the grass without allowing any part of them to be seen. Some time after this I had an opportunity of testing the nimbleness of their toes. It was with a Murray black. I told him what I wanted to see, and he was very willing to display his cleverness. I put a sixpence on the ground and placed him by my side. Watching his operations, I saw him pick up the thin coin with his great and first toe, just as we should with thumb and forefinger; bend his leg up behind him, deposit the money in his hand, and then pass it into mine, without moving his body in the very slightest degree from the vertical."—Flinders Land and Sturt Land, by W. R. H. Jessop, M.A., vol. II., p. 283.

- ↑ Te Ika A Maui, p. 13.

- ↑ Tribes in the Central part of Victoria, by W. E. Stanbridge, F.E.S.

- ↑ The Report of the Select Committee of the Legislative Council of Victoria.

- ↑ The Narrinyeri, p. 84.

- ↑ Natives of the Port Lincoln District, South Australia.

- ↑ North-West and Western Australia, vol. I., pp. 253-5.

- ↑ Discoveries in Australia, by Capt. Stokes, R.N., vol. I., pp. 88-9.

- ↑ Voyage de Découvertes aux Terres Australes, 1800-4.

- ↑ English Colony in New South Wales, by Lieut.-Col. Collins, 1804.

- ↑ Interior of Eastern Australia, by Major (Sir Thomas) Mitchell, 1838.

- ↑ Our Antipodes, by Lieut.-Col. Mundy, 1857, p. 46.

- ↑ From Port Macquarie to Moreton Bay, 1845.

- ↑ Overland Expedition from Rockhampton to Cape York, 1867, p. 82.

- ↑ Narrative of the Voyage of H.M.S. Rattlesnake, by John Macgillivray, F.R.G.S., 1852.

- ↑ Dampier's Voyages, vol. I., p. 464.