The Aborigines of Victoria/Volume 1/Chapter 10

The coverings and ornaments used and worn by the Australian natives—male and female—are fully described in the notes prepared at my request by the late Mr. William Thomas, and in the letters and memorandums furnished in reply to questions put by me, by Mr. John Green, of Coranderrk, the Rev. Mr. Bulmer, of Lake Tyers, in Gippsland, and Dr. Giuiimow, J.P., of Swan Hill.

The males paid attention to their weapons rather than to their dress; and the females relied more on the attractions presented by their forms unadorned than on the necklaces and feathers which they carried. The proper arrangement of their apparel, the ornamentation of their persons by painting, and attention to deportment, were important only when death struck down a warrior, when war was made, or when they assembled for a corrobboree.

In ordinary life little attention was given to the ornamenting of the person. Different from the women of Polynesia, the Australian females seem to have no love for flowers. The rich blossoms of red, purple, and yellow, so abundant in the forests, are never, or very rarely, twined in their hair, or worn in rich garlands around the neck: nor do they deck themselves with the bright plumage of birds. A warrior may wear a plume, but his daughters are content with the grey, hair-like feathers of the emu for the slight covering which decency demands. Nor did they use in Victoria—as far as I can gather—the gaily-colored shells of the sea-shore for necklaces, as the Tasmanians did.[1]

The men had no ear-rings of gold, nor armlets of silver: none of the metals were known to them; and no precious stone—not a piece of jade even—was worn by them: yet their rugs of skin; their aprons of feathers or skins; their necklaces of reeds or teeth; their head-bands of fibre; their dresses of boughs for the dance—are not without interest.

I believe I have gathered together all that is known of the dress and ornaments of this people; and my correspondents have been careful in making enquiries and exact in giving information. The dress and ornaments of the Aborigines of the Yarra tribe were, according to the information afforded by the late Mr. Thomas, as follows:—

1. The opossum rug, called Waller-wal-lert. It hung loosely about the body, had a knot at each upper corner, and was fastened by a small stick thrust through holes made by the bone-needle—Min-der-min. It could be cast off in a moment. It was carried or worn when travelling, but in the camp it was usually kept in the miam. In making an opossum rug some skill and knowledge are employed. In the first place, it is necessary to select good, sound, well-clothed skins. These, as they are obtained, are stretched on a piece of bark, and fastened down by wooden or bone pegs, and kept there until they are dry. They are then well scraped with a mussel-shell or a chip of basalt, dressed into proper shape, and sewn together. In sewing them the natives worked from the left to the right—not as Europeans do—and the holes were made with the bone awl or needle, and instead of thread they used the sinews of some animal—most often the sinews of the tail of the kangaroo.

The rug was usually ornamented on the inside. Lines straight, of herring-bone pattern, or sometimes representing men and animals, were drawn with a sharp bone-needle, and filled in with color.

2. The band around the forehead, called Leek-leek. In this band is placed a feather from the native companion, the eagle, or the lyre-bird. Sometimes the native put his tomahawk, or some other small article, in this band; but the tomahawk was usually carried in the belt that is worn about the waist.

The Leek-leek was usually made of the sinews of the tail of the kangaroo, but often of the sinews of other animals, if these could not be obtained. The Leek-leek was fashioned by the women, as a rule; but young men often amused themselves by making this ornament.

3. The bone, or a piece of reed, worn in the septum of the nose, called Noute-kower. The bone of some animal—generally a bone somewhat curved—three or more inches in length, was passed through a hole made in the septum of the nose, and carried joyfully, as something likely to gain favor with both sexes.

4. The reed-necklace. Reeds cut into short pieces—of different lengths and different diameters—were strung on twine made of the wool of the opossum, or of some fibre, and hung round the neck in many folds, falling in some cases quite down to the chest. The reed-necklace was called Kourn-burt. Another necklace, worn sometimes, was made of the sinews of the legs of the emu. This was formed into a kind of net, and was called Kour-ur-run.

|

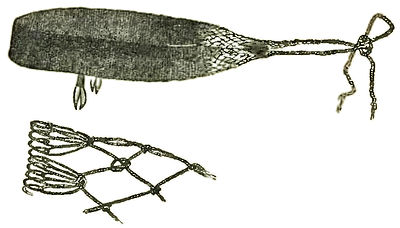

| FIG. 22. |

5. The ornaments worn around the loins. Strips of the skin of some animal, fashioned as shown in Fig. 22, were tied with some fibre around the loins, so as to conceal the lower parts of the body in front and behind. These ornaments were called Murri-guile.

6. The band around the arm, called Yel-un-ket-ur-uk. A band made of the skin of a small flying squirrel (Tuin-tuin) was fastened around the arm to give strength.

7. The hunger-belt. The native used occasionally a belt, made of the skin of the native dog (Wer-ren-Willum), which was worn round the waist, and so arranged as to admit of its being tightened when required. The fur of the animal was outside, and the skin pressed against the body. This belt was called Ber-buk, and it was used chiefly when travelling rapidly, or on some expedition requiring secresy, in the course of which the native might have difficulty in procuring food or water. When oppressed by hunger, the belt was tightened.

In traversing country occupied by a hostile tribe, the native might be afraid of even taking an opossum from a tree. The noise made by cutting steps with his tomahawk would be sufficient to attract attention in a still night. Fearful and anxious, yet bent on performing what he conceived to be his duty, resorting to many stratagems—walking backwards in soft sand or loamy ground; crouching in the day time, and making rapid journeys in the night—hunger and thirst would have overcome him but for his belt. Tightening it more and more, and having still a craving appetite, he would doubtless deal with his enemy, when he found him, with less mercy by reason of such sufferings.[2]

Mr. Thomas has given but little information respecting the dress and ornaments of the females. In his notes I find that the band tied round the forehead of the females was called Murra-kul. It was made of the fur of the opossum or the hair of the native cat. The fur was twisted into threads by the hand, in the same manner as the material for net-bags was prepared.

The young females wore, not as a garment but for preserving decency, a skirt or girdle (composed of the fur of the opossum) called by them Leek-leek.

|

| FIG. 23. |

The Til-bur-nin, or apron (Fig. 23), worn by adult females when dancing, is made of the feathers of the emu. The feathers are attached to a strong cord, generally made of the sinews of the tail of the kangaroo, and they are worked in, six or more together, by fine sinews or fine cord made either of some fibre or of the fur of the opossum. It forms a thick but short apron, in length six feet or more, and when wound round the waist descends not quite half-way to the knee. It is fastened by a knot. One specimen in my possession is very well fashioned. The cord, made of the fur of the opossum, is double, and the shafts of the feathers are bound and secured to the cord by extremely fine sinews. The whole is neatly wrought, and the feathers are so arranged as to hang gracefully, even when the cord is twisted.[3]

The kangaroo bag, carried by the males, sheltered them from storms at times, and therefore may be described here. The large kangaroo bag, Bool-la-min-in or Moo-gro-moo-gro, is used and carried by the males only. When not engaged in hunting, the Aboriginal keeps his tools and implements in this bag, his Leange-walert, teeth of animals, mussel-shells, bits of quartz and black basalt, &c., &c. When engaged in hunting, he starts in the morning with the bag almost empty. It contains only his tomahawk, waddy, and wonguim; and all the game he secures during the day is put into the bag. If successful, he has a heavy load to carry back to his miam, the bag itself not being very light. The bag is made of the skin of the kangaroo, which is taken from off the animal with the greatest care, cleaned with a basalt-chip and mussel-shell, and stretched on pegs and dried in the sun. The ends are brought together and tied with strings made of grass, and a grass rope is attached to the ends, so as to enable him to sling the bag over his shoulder. The kangaroo-skin bag is now rarely seen south of the River Murray.

Mr. John Green says the full dress of an Aboriginal man, when prepared for the dance in the corrobboree, was as follows:—Around the head and crossing the forehead a piece of the skin of the ringtail opossum was worn, the ornament being called by them Jerr-nging; a feather of the tail of the lyre-bird was inserted between the band and the forehead (named Kan-kano), and around the neck and the biceps of each arm were worn ornaments made of reeds, like necklaces (Tarr-goorrn). Suspended from the loins by a cord, and hanging in front, was a strip of opossum skin (Barran-jeep). Each ankle was decorated with small boughs (Jerrang), and in the hands were held two sticks (Nanalk) for beating time. The body was painted with white clay. The double line of horizontal stripes on the chest was named Bikamnop, and the straight lines from the cord around the loins to the ankles were called Beek-jerrang.

The ornaments worn by a female of the Yarra tribe were few and simple. In the septum of the nose was inserted a piece of the bone of the leg of a kangaroo, called Ellejerr; around the neck was worn a very long reed-necklace (Tarr-goorrn), and around the loins was fastened the usual apron made of emu feathers and sinews, called Jerr-barr-ning (Til-bur-nin).

The Rev. Mr. Bulmer has given me a description of the ornaments which were worn by the natives of Gippsland in the olden time. The natives, he says, were fond of ornaments of their own manufacture, and, not able to decorate themselves with articles made of gold, silver, or other metals, or with precious stones, they strove to make their appearance agreeable by using such adornments as the materials within their reach enabled them to fashion. Round the forehead (Nern) the males wore a piece of network, made of the fibre obtained from the bark of a small shrub which grows plentifully near Lake Tyers. The length of the band was from nine inches to one foot, and the breadth about two inches. It was called Jimbirn. It was worn sometimes by females, but very seldom; and was always regarded as belonging to men. The Jimbirn was useful as well as ornamental, as it kept the hair from falling over the eyes.[4] To the Jimbirn was attached an ornament, made of the teeth of the kangaroo—Nerndoa jirrah (nerndoa, teeth; jirrah, kangaroo)—and string formed of the wool of the opossum, which was so arranged as to cause the teeth to hang on each temple. At the back of the head was suspended from the string which fastened the Jimbirn a wild dog's tail—Wreka baanda (wreka, tail; baanda, dog). This much resembled the cue, which was thought becoming some few years ago in Europe. Over the ears and pointing to the front was placed the fur of the tips of the ears of a native bear (Koola), called by the natives Kinanga Koola. Over the forehead was worn sometimes the feather of the eagle, a tuft of emu feathers, or the crest of a cockatoo. This ornament answers to the tuft of feathers with which military men decorate their hats and helmets. The hair was always well greased, and plentifully sprinkled with ruddle, called by the natives Ni-le. Mr. Bulmer says he has never seen any ear-ornaments. They never, he thinks, pierced the ears. But it was considered proper to bore the septum of the nose. Indeed it was ordained that the septum should be pierced, and that each person should wear in it a piece of bone, a reed, or the stalk of some grass, the name of the ornament being Boon-joon. The old men used to predict to those who were averse to this mutilation all kinds of evils. If it were omitted at the proper time, the sinner would suffer—not in this world, but in the next. As soon as ever the spirit—Ngowk—left the body, it would be required, as a punishment, to eat Toorta gwanang (filth—not proper for translation). To avert a punishment so horrible, each one gladly submitted, and his or her nose was pierced accordingly.[5] Around the neck were worn a few strings of beads, made of reeds called Thaqui, or of opossum fur (Kyoong). Wrapped around the right arm were worn a few strips of the skin of the ring-tail opossum (Yunda-bla-ang). This list includes all the ordinary articles of adornment used by the natives of Gippsland.

Mr. Bulmer once asked a native why he wore such things, and he replied that he wore them in order to look well, and to make himself agreeable to the women—a motive that, in Mr. Bulmer's opinion, is not confined to the blacks. Many will agree with Mr. Bulmer.

When prepared for the corrobboree, the men had suspended from their waist-belts bunches of strips of skin, both before and behind; but usually they had no covering of any sort. What they did wear was not as clothing, but as ornament. They painted themselves for this dance. Ordinarily, they smeared their cheeks with ruddle, but for the dance they painted their bodies. They seemed to desire to make themselves as hideous as possible. They marked each rib with a streak of white pipeclay (marlo), and streaks were drawn on their legs and arms and on their faces, so as to make themselves appear, in the flickering and flaming of the camp-fires, as moving skeletons. Mr. Bulmer believes that they so painted their bodies with the design of making themselves terrible to the beholders, and not beautiful or attractive. An Australian native is wise: that man who could make himself appear very hideous at a corrobboree—who could by his art attract all eyes—was not likely to be forgotten on the next day. And as much care would be employed to attain this as the other position depending on the milder efforts of the toilette.

The ornaments worn by the females were not much regarded by the men.The woman did little to improve her appearance. She was the worker, the carrier, often the food-winner; and if her physical aspect was such as to attract admirers, she was content. Her chief ornament was the string of beads—Thaqui. From her waist was suspended—not so much for ornament as for a covering—a piece of fringe about four inches in depth. This was called Kyoong, and was worn by girls until they attained a marriageable age. While she wore the Kyoong she was called Kyoongal Woor-kut—that is, a girl who wears the Kyoong. It was the duty of the mother, at the proper time, to remove the Kyoong; but it frequently happened that the girl would elope with some young man, and take it off herself—which invariably gave rise to scandal, base suggestions, and quarrels. Nearly all the ornaments, Mr. Bulmer says, were made by the females.

The dress of the male Aboriginal of the Lower Murray, according to information furnished by Dr. Gummow, of Swan Hill, consisted only of the opossum rug, called Pir-ri-wee. The female also used a rug as a covering; but by both males and females it was worn only on cold days, or when moving from camp to camp. On ordinary occasions the females wore nothing more as a dress than the apron of emu feathers, called by the natives of the Lower Murray Mor-i-uh. This was cast aside after the birth of a child.[6]

The young males wore wallaby skins, cut into shreds and fastened by a string around the loins. It was worn until the whiskers grew, and the upper incisors—Wid-don-wo-ri—were knocked out.

The women, when travelling, carried a bag made of the leaves of some aquatic plant or flag, in which their fish, game, and yams were placed. The bag was called Koorn-goo. Each man also had a bag, but larger, in which he carried kangaroo and emu meat. This bag, too, was called Koorn-goo.

Dr. Gummow has sent me specimens of the ornaments worn by the natives of the Lower Murray:—

|

| FIG. 24. |

The band tied round the head, extending from the occiput over the parietal bones to the place of the frontal suture, called Mar-rung-nul, is shown in Fig. 24. This specimen was obtained by Dr. Gummow from one of the old natives. This ornament is closely woven, and to the eye resembles a thick coarse cloth, but it is really soft and pleasant to the touch. It is made of the fibrous root of the wild clematis (Mo-u-ee). It is exceedingly strong. The length of the band is twelve inches, and the breadth one inch and a quarter. Dr. Gummow says that these bands are usually made by the women. Wing feathers of the cockatoo are stuck in the band, one on each side of the head. The feathers are called Wyrr-tin-nay. This band is worn by males only.

Mr. A. F. Sullivan, of Bulloo Downs, Cuunamulla (Queensland), gave me a specimen of the Mar-rung-nul, made of the fur of the opossum. It is very soft, and well and closely woven. The band is fourteen inches in length. When worn by the natives, it is made white with clay or burnt gypsum.

|

| FIG. 25. |

The band of network (Fig. 25) Dr. Gummow says is named Moolong-nyeerd. It is worn across the forehead, with the kangaroo teeth as pendants, which, when lashed together, are known as Leangerra. When stretched, as it would be when on the head, the broader part of the network is nearly twelve inches in length and three inches in breadth. The open network on each side up to the knot is four inches in length. The material is the fibre of some aquatic plant, twisted and formed into a fine, hard, durable twine. The teeth are fastened neatly with the tail sinews of the kangaroo (Wirr-ran-nee). It would not be easy to find anywhere a more highly-finished piece of work of its kind than this. The wider part is beautifully knitted. This band was worn both by males and females.

|

| FIG. 26. |

The sash or band of network, called Ni-yeerd (Fig. 26), is worn as a belt round the loins. In it the native carries the Wan-nee (boomerang), or the tomahawk or other weapon. This specimen, which was sent to me by Dr. Gummow, is not inferior to any other piece of network I have seen. The twine, formed of the fibre of some flag, is uniform in thickness and evenly twisted; and the meshes are all of the same size. It is very strong and elastic, and as well fitted for the purpose desired by the native as if it had been manufactured expressly to his order by the most accomplished of Europeans. It is six feet four inches in length. Its general character, and the manner in which it is knitted, are shown in the engraving.

Dr. Gummow has carefully described the several ornaments worn by the natives of the Lower Murray in the letters, memorandums, and drawings which he has sent to me. He thus speaks of the bone, Mellee-mellee-u, which is carried in the septum of the nose:—"Enclosed is a sort of awl made from the thigh-bone of the emu, called Pin-kee, which is used for boring the septum of the nostrils, also for perforating opossum skins when sewing them together to form rugs (Pirri-wee). The sinews of the kangaroo tail were used as thread, and called Wirr-ran-nee. After using the perforator called Pin-kee for piercing the septum of the nose, a piece of reed is slipped on to the point as a canula, and as the Pin-kee is withdrawn, with the reed as a sheath, the latter is left to act as a tent, so as to dilate the opening. Gradually increasing the size of the reeds until the opening is sufficiently large, the Mellee-mellee-u—a piece of bone from the leg of the emu or the kangaroo—is finally inserted, and this remains in the septum of the nostrils of the males until the front teeth are knocked out. The females undergo the same treatment, and wear during their lives a ring of bone, cut from the wing of the bustard (Narroo-vee). The ring, called Kolko, is rather more than one-third of an inch in length, and the diameter is two-thirds of an inch. The aperture in the ring forms a foramen between the nostrils."

Dr. Gummow's specimens of the ornaments described by him are very valuable; and as he has obtained from old natives the names and uses of the several specimens, his contributions are of more than ordinary interest.

The natives of Cooper's Creek, according to Mr. Howitt, sometimes place feathers in the nose, instead of a bone.

|

| FIG. 27.—(Scale ⅓) |

This necklace (Fig. 27) was very common many years ago; but the only examples I have seen have been obtained in the western districts of Victoria. It is formed of a long strip of well-dressed kangaroo skin, to which are attached the teeth (incisors) of the kangaroo.[7] Each tooth is fastened to a small piece of skin by the tail sinews, and is neatly fixed to the long strip by knots passed through incisions. The skin is stained with red-ochre; and the contrast of colors is not unpleasing. The specimen here figured is in the possession of Mr. E. von Guerard, the well-known landscape painter.

|

| FIG. 28. |

The reed-necklace (Fig. 28) commonly worn by the Australian females (and not seldom by the males) is named Jah-kul by the natives of Lake Hindmarsh, and Kor-boort or Tarr-goorrn by the natives of the Yarra. The reed is called Djarrk. Pieces of reed—in length from a half to three-quarters of an inch— are strung on twine made either of some fibre or the hair of the opossum; and, when extended, the necklace is thirty feet or more in length. In the example here figured there are four hundred and seventy-eight pieces of reed. This light and not inelegant ornament is greatly prized by the young females, and they expend a great portion of their time in making necklaces of this pattern. A reed-necklace, worn both by males and females, and named by the natives of the Lower Murray Kill-lid—formed of pieces of reed half an inch in length, and little more than a sixteenth of an inch in diameter—was presented to me by Dr. Gummow. It is well made. The fibre on which the sections of reed are strung is very fine indeed, and I cannot conjecture how it was manufactured. Dr. Gummow says that this kind of necklace was of different sizes—according as it was intended for the male or the female.

|

| FIG. 29. |

This necklace (Fig. 29) was found in a basket, described in another place, which was dropped by a woman of the Burdekin tribe, when surprised by a party of whites. The string is made of the fibre of some root, wrought into a very strong but thin twine. On this twine are strung short sections of a reed. The pendant is composed of twine coated with gum, on which are fastened human hair, feathers, and shells (unio), by a wrapping of twine made of the fur of the opossum. This ornament exhibits in its manufacture more of neatness and delicacy than is usually seen in native work. It was sent to me with the native bag in which it was found by the late Mr. Matthew Hervey.

|

| FIG. 30. |

|

| FIG. 31. |

I have received from Mackay, in Queensland, through the kindness of Mr. Bridgman, an ornament which is used as a decoration by the natives of the Far North. It is worn round the forehead, and is named Ngungy-ngungy. The shells—fragments of the nautilus—are ground into form and strung on a fine twine made of the fibre of some plant.—(Fig. 30.) Larger pieces of shell—also of the nautilus—are worn on the breast, suspended from the neck, and are called Carr-e-la. These are also strung on twine of the same kind as that used for the stringing the smaller pieces.—(Fig. 31.)

|

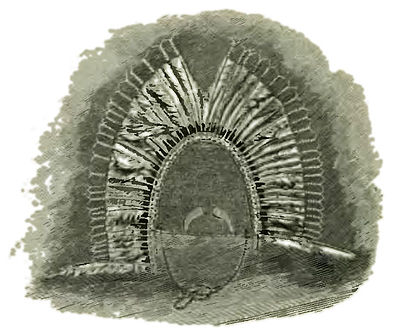

| FIG. 32. |

Mr. J. A. Panton has sent me a very curious head-dress (Oogee)—(Fig. 32)—which is worn in the corrobboree dance by the men of Cape York. It is formed on a framework of sticks. The feathers of the cockatoo are notched at the ends (except the lower feather at each side), and the quills are turned over the curved stick, and very neatly tied with twine. The inner arch is strengthened at the back by sticks, and the cloth which covers them is exactly like canvas. The two spaces which would appear just above the eyes when the head-dress was worn have a border of thick twine. They are colored with red-ochre, as is also the edge of the inner circle. The whole is ingeniously constructed; and the white and yellow of the feathers, and the red paint, must have appeared hideous by the light of the corrobboree fires.

Mr. Wilhelmi says that in the north-west the men decorate their heads after a strange fashion, on occasions of rejoicings and when engaged in their mystic ceremonies. They place in the head-band, behind the ears, two small pieces of green wood, decorated from one end to the other with very thin shavings, which appear like a plume of white feathers. The sticks are so placed as to admit of their being tied together in front, and at a distance they resemble two long horns. The Port Lincoln blacks get white birds' down, and make a sort of wreath, which looks not unlike a woman's cap.

A head-dress of feathers is also worn by the old men at Cooper's Creek.

On the Macleay River, at the ceremony of initiation, the men wear high top-knots of grass, while others tie the hair in a knot, and cover the head with the snowy down of the cockatoo.[8]

In other parts a plume of white cockatoo feathers is worn. Sir Thomas Mitchell saw, near the River Bogan, some rather curious decorations. One had a kind of network, confining his hair in the form of a round cap, from the front of which arose a plume of white feathers. A short cloak of opossum skin was drawn tight round his body with one hand, and with the other he grasped his boomerangs and waddy. At another spot he saw two natives with hideous countenances, and savagely painted with crimson-red on the abdomen and right shoulder, the nose and cheek-bones were also gules, and some blazing spots were daubed like drops of gore on the brow. The most ferocious wore round his brow the usual band newly whitened.[9]

Some were seen by the same explorer with the nose and brow painted with yellow-ochre; and a boy, led by a man, was so dressed with green boughs that only his head and legs remained uncovered. Emu feathers were mixed with the wild locks of his hair, and he presented altogether a strange spectacle. On the Darling, at a native dance, the men were hideously painted, so as to resemble skeletons.

As far as I have been able to learn, yellow is most commonly used for purposes of decoration in the north and north-eastern parts of Australia.

Mr. Samuel Gason gives the following list of ornaments worn by the Dieyerie tribe:—

| Kultrakultra | Necklace made of reeds, strung on woven hair, and suspended round the neck. |

| Yinka | A string of human hair, ordinarily three hundred yards in length, and wound round the waist. This ornament is greatly prized, owing to the difficulty of procuring the material of which it is made. |

| Mundamunda | A string made from the native cotton-tree, about two or three hundred yards long; this is worn round the waist, and adorned with variously-colored strings wound round at right-angles. These are worn by the women, and are very neatly made. |

| Kootcha | Bunch of hawk's, crow's, or eagle's feathers, neatly tied with the sinews of the emu or wallaby, and cured in hot ashes. This is worn either when fighting or dancing, and also used as a fan. |

| Wurtawurta | A bunch of the black feathers of the emu, tied together with the sinews of the same bird, worn in the Yinka (girdle) near the waist. |

| Chanpoo | A band about six inches long, and two inches broad, made from the stems of the cotton-bush, painted white, and worn round the forehead. |

| Koorie | A large mussel-shell pierced with a hole, and attached to the end of the beard or suspended from the neck. Also used in circumcision. |

| Oonamunda | About ten feet of string, made from the native cotton-bush, and worn round the arm. |

| Oorapathera | A bunch of leaves tied at the feet, and worn when dancing, causing a peculiar noise. |

| Unpa | A bunch of tassels, made from the fur of rats and wallaby, worn by the natives for the sake of decency. They are from six inches to three feet in length, according as they are intended to be worn. |

| Thippa | Used for the same purpose as Unpa. A bunch of tassels made from tails of the native rabbit, and, when washed in damp sand, very pretty, being white as snow. It takes about fifty tails to make an ordinary Thippa, but some Mr. Gason has seen consisting of three hundred and fifty. |

| Aroo | The large feathers from the tail of the emu, used only as a fan. |

| Wurdwurda | A circlet or coronet of emu feathers, worn only by the old men. |

- ↑ The Tasmanian necklace is described elsewhere. The late Mr. Thomas states in one of his papers (referred to in another part of this work) that Aboriginal girls are sometimes decked with flowers when they dance together. I have never seen the natives use flowers for ornamenting their persons. Careful enquiries have been made, and it would appear that they are not so used commonly in any part of Australia.

- ↑ Speaking of the Moors of Africa, Winwood Reade says that they are remarkably hardy, and can pass days without eating or drinking. On such occasions they wear, like the Red Indians, a hunger-belt, which they gradually tighten.—Savage Africa, by W. Winwood Reade, p. 444.

- ↑ The ancient Egyptians used the Til-bur-nin. Young girls wore "a girdle, or rope, of twisted hair, leather, or other materials, decorated with shells, round the hips."—The Ancient Egyptians, Wilkinson, vol. II., p. 335.

- ↑ The fillet was used by the Egyptians, but whether to bind the natural hair or the wig is not clear.—(See Wilkinson: The Ancient Egyptians, vol. II., p. 325.)

The Chaldæans wore "a band of camel's hair—the germ of the turban which has now become universal throughout the East."

Amongst the Assyrians, "if the hair was very luxuriant, it was confined by a band or fillet, which was generally tied behind the back of the head" (like the Egyptian fillet).

The rich worshippers who brought offerings to the gods in Babylonia "had a fillet, or head-band—not a turban—round the head."—Rawlinson: The Five Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World.

Some of the Ancient Persians wore round the head a twisted band, which resembled a rope.

The Greeks and the Romans wore fillets.

Dido bids Barce bind her head in these words—

The infulæ and vittæ—a sort of white fillets—were used in Roman sacrifices. The Italian lista, the French bande, and the English bandeau, or brow-band, are little different from the Aboriginal head-band. Shoemakers wear a band round the head, so as to keep the hair from falling over their eyes when they are at work; and until lately the bandeau was worn by English ladies. It is certain that the Jimbirn is more ancient than these.

"Tuque ipsa piâ tege tempora vitta."

- ↑ It is very singular, says Mr. Bulmer, that the natives, who have no form of religion, should have a distinct idea of a spiritual existence. They think that the soul, as soon as it leaves the body, goes off to the east, where there is a land abounding in sow-thistles (Thallak), which the departed eat and live. The spirits are sometimes prevented from reaching the happy land by the moon, which devours them if they encounter it, and indeed feeds on stray mortals and spirits of departed men and women. When the moon is red, they see proof that it has eaten plentifully of its favorite food.

- ↑ Some article of dress or ornament worn for the purpose of distinguishing the maiden from the wife seems to be necessary to a people in a state of savagery or barbarism. The snood used by maidens in Scotland is no doubt very ancient.

- ↑ Dr. Gummow informs me that the incisor teeth of the lower-jaw of the kangaroo—such as are used for a necklace of this kind—are named Lean-now.

- ↑ From Port Macquarie to Moreton Bay, by C. Hodgkinson

- ↑ Eastern Australia, by Major T. L. Mitchell.