The Aborigines of Victoria/Volume 1/Chapter 14

Some six years ago I asked Mr. H. Y. L. Brown, who was then engaged in making a geological survey of part of the Colony of West Australia, to procure for me some of the weapons of the natives of the west and north-west coast of Australia; and he was good enough to send me a very valuable collection, which I have used in preparing this brief account of some of the more important implements employed by the blacks in this part of the continent. In order that accurate descriptions of them might be given, I applied to the Honorable Fred. Barlee, the Colonial Secretary at Perth, to supply information respecting some of them; and with his usual kindness, and with an alacrity in the promotion of scientific investigations not always found in gentlemen occupying similar exalted positions, he furnished valuable notes, made by himself, from statements communicated to him by an intelligent native.

No one but a person who has engaged in such labors as have occupied me for many years knows how difficult it is to ascertain the facts respecting even the commoner implements and utensils used by the natives. I have had the most positive statements respecting the use of one kind of spear absolutely contradicted by other statements apparently equally trustworthy; and in all such cases it has been necessary to apply to the blacks themselves for an explanation. A spear of a peculiar form is employed in one locality almost exclusively as a weapon of war; in another it is commonly used for striking fish; and in a district not far distant perhaps it is altogether unknown.

With such difficulties to encounter, it was with peculiar satisfaction that I was able to avail myself of the aid of gentlemen of culture and experience in procuring some few data for this necessarily imperfect description of the West Australian weapons and utensils.

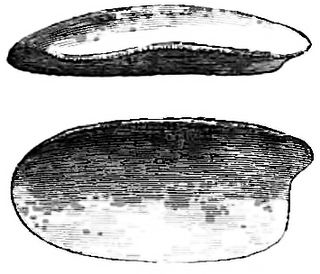

Perhaps the most interesting of all the offensive weapons used by the natives of the western part of the continent is the Kylie or boomerang. It is essentially the same as that found in the southern and eastern colonies, but it is somewhat different in form, and is exceedingly thin and leaf-like. Some of those in my possession are scarcely three-tenths of an inch in thickness in the thickest parts, and they have knife-like edges. The weight of the heaviest is four and three-quarter ounces and the lightest a little under four ounces. The extreme length varies from twenty inches to twenty-three inches, and the breadth is from one and three-quarters to two inches. At first sight they appear to be quite flat; but a close examination shows that there is a slight twist; and in weapons so thin as these a very small deflection is sufficient to ensure their true flight and their return to the thrower. They are made by the natives with wonderful precision and accuracy, and they are dangerous weapons in their hands. Common forms of the Kylie are shown in Fig. 140.

|

| FIG. 140.–(Scale 1/10.) |

Some years ago, as already stated, I took one of the West Australian boomerangs to Coranderrk, and showed it to the natives. They were much surprised, and seemed at first scarcely to believe it to be a boomerang made by an Australian; but "Tommy Farmer," an intelligent fellow, handled it carefully, and sought to discover whether it was one that would come back. He then threw it, and it made a large circuit, and returned to him. All the West Australian boomerangs seem to fly further than those used by the natives of the east.

The wood of which my specimens are made appears to be that of some species of acacia, and in forming them advantage has been taken of a natural curve of the wood. They are not carved or artificially colored; but they are, nevertheless, very beautiful implements, on account of the natural tints and veins of the wood. Some are of a rich reddish-brown, with streaks of dark-brown, and the edges are cream-colored.

| FIG. 141. | FIG. 142. |

The most common form of spear in use in West Australia is that shown in Fig. 141, where the head alone is given. It is named Gid-jee, Gee-jee, or Borral (spear-stone). It is about eight feet in length, and is thrown with the Meero (or Womerah). The heads of those in my collection are coated with a hard gum, forming a ridge on one side, in which pieces of glass are impacted, and the whole is stained with the gum of the xanthorrhœa, to render it smooth and impervious to moisture. They weigh from six and a half ounces to seven ounces. The woods used for making this weapon are Boordono, which is the best; Woonarra, which is good; and Goodgidgee, which is common. Mr. Barlee could not ascertain the botanical names of the trees from which these woods are procured. The cutting tools used in making the spear are shells and quartz, or glass, if it can be procured. The point is very sharp. When threatening an enemy, a native will say, Ngad-jol nhynueen daanaga—"I will you spear!"

The light spear (Fig. 142) is formed entirely of very hard wood, and is eight feet in length. It is sharpened at both ends, and each end is brought to a very fine point. It cannot, of course, be thrown with the Womerah. In the thickest part the diameter does not exceed four-tenths of an inch, and it weighs eight ounces. The only specimen from West Australia that I have in my possession was obtained by Mr. H. Y. L. Brown, and it is conjectured that it is used both in hunting and in war. It is a light and well-balanced spear; and great skill must have been employed in shaping it and in bringing the ends to such fine hard points as they present. The wood of which it is made has dark veins in it, and it appears to have been polished and rubbed or varnished with some sort of gum or resin.

|

|

| FIG. 143.–(Scale: ⅓.) | FIG. 144. |

A rather remarkable spear, Fig. 143, is the only one brought from West Australia by Mr. Brown which is in any way ornamented. The shaft from the point downwards is scraped smooth for a length of nearly nine inches, and marked with black bands; and the wood being white, the effect is peculiar. Below the scraped or polished part the wood is in the same state as when the bark was peeled off, except that it has been rubbed with a gum or resin to protect it from the wet.

The spear is nearly eight feet in length. One weighs five and three-quarter ounces, and another six and a half ounces. The barb is formed of very hard white wood, and is exceedingly thin and sharp. It is firmly fixed to the head by some kind of string or sinew, and further strengthened by a coat of the gum of the xanthorrhœa. The lower end is hollowed for the reception of the point of the Womerah, and one is tied (as shown in the figure), to strengthen it. As a weapon of offence, it would be highly dangerous. It resembles the barbed spear of the Cape York natives.

The double-barbed spear—Pillara—(Fig. 144)—is thrown from the Womerah like the Gid-jee, but is employed more commonly in close combat, when it is thrust at the enemy. The wood from which this weapon is made is not known, and it is not used within a distance of four hundred miles north of Perth. It is about nine feet in length. It is stated by the Rev. J. G. Wood[1] that this spear is in use at Port Essington; and this agrees with the information furnished by the Honorable Mr. Barlee.

The four-pronged spear (Fig. 145) is about six feet in length, the tapering heads being apparently of the same kind of wood as the shaft. The barbs on each side project outwards. Though this is named as a West Australian weapon, it is not known, as far as could be ascertained by the Honorable Mr. Barlee, to any of the natives of Perth. It is supposed to be a weapon in use at Port Darwin, or on some part of the north or north-west coast.

A three-pronged spear, barbed at each point, somewhat similar in construction to this, is in use amongst the natives of Cape York.

|

| FIG. 145. |

|

| FIG. 147. |

|

| FIG. 146. |

The Meero or Womerah, the lever for propelling the spear, differs in form from those in use in Victoria, though the principle is the same. The flat, shield-like Womerahs (Fig. 146) in my collection are made of djarrah, and are very thin and well polished. They are not ornamented in any way. The point for receiving the end of the spear is made of very hard white wood, and is fastened to the head with gum; and there is a lump of gum at the end, so placed as to prevent the implement from slipping in the hand. The length is one foot ten inches, and the greatest breadth five inches. The weight varies from seven and three-quarter ounces to ten ounces. Mr. Barlee informs me that this implement is usually made of Mang-art, a species of wattle, called raspberry-jam, from the scent of the wood being like that preserve. The natives carve the wood into proper form with the stone-chisel, and smooth it with a rasp made of the rough bark of any forest tree.

Fig. 147 is another form of the throwing-stick in common use amongst the natives of the north-west coast. I have in my possession a good specimen sent to me from Port Darwin by Mr. J. G. Knight.

The wooden shield (Woonda) of West Australia (Fig. 148) is two feet nine inches in length, and six inches in breadth. It is made of the wood of a species of bastard cork-tree (botanical name not known), and the hole for the hand is cut out of the solid block. Its weight is thirty ounces. Is is curiously ornamented. The grooved ridges, forming straight lines from the points, take a sudden turn near the middle, where they unite. The dark lines in the engraving represent the ridges which are hollowed or grooved, and these grooves are filled in with ruddle. The hollow parts between the ridges are painted white, thus forming alternate stripes of bright-red and white. Why the shields are ridged and grooved has not been ascertained. As only one form of shield is known in West Australia, it must be inferred that it is used both as a guard against spears and clubs; and Mr. Barlee says that the natives consider it a sufficient protection for their bodies when in a half-kneeling or stooping position. It is rough-hewn with the stone-chisel, and carved and finished with the teeth of the opossum or kangaroo-rat.[2] The red color for ornamenting it is prepared from a yellow clay (Wilgee), which is burnt into red-ochre, and the white from a sort of pipeclay (Durda-ak).

|

| FIG. 148. |

All the shields from West Australia are ornamented in the same manner, and the form, as far as I am able to ascertain, is the same everywhere on the west and north-west coast.

It is somewhat strange that we should find in Central Africa a shield very closely resembling that used by the natives of West Australia. The Neam-nam, in the Nile district, just under the Equator, have a weapon nearly of the same size and form as that of the West Australians, and, like it, the hole for the hand is scooped out of the solid block.[3] The Neam-nam shield is usually covered with the skin of an antelope, but it appears some are carved and colored. Mr. Alexander Williams, in Notes and Queries, says that the late Mr. Christy called his attention to the exact similarity of the shields of the West Australian blacks to those used by the natives of Central Africa—"a similarity not only in shape and pattern but actually in the succession of colors in the pattern."[4]

It is certainly remarkable that the shields of the natives of the west of Australia should differ so much in their character from those of the natives of the south and the east.

The Kadjo or Koj-jer—native hammer or tomahawk—(Fig. 149)—differs from all others known on the continent of Australia, and indeed an implement exactly similar has not been found, it is believed, in any part of the world. I have two specimens, and they are alike. One edge is chipped, so as to be of use in cutting and chopping, and the other is blunt, and may be employed as a hammer. The stone is a fine-grained granite—one is almost pure quartz—and the edge and the head are formed by percussion. They are not ground. The wooden handle is formed of hard wood like that used for spears, namely, Boondono or Mang-art, and is about four-tenths of an inch in diameter and seven inches in length. The handle is fixed to the stone by gum obtained from the tough-top xanthorrhœa, being stronger and more adhesive than that got from the brittle-top xanthorrhœa. It is said that two stones are used in forming the head, and it is not unlikely from the manner in which the handle is inserted that this is so; but the only way in which I could ascertain the mode of construction would be by breaking a tomahawk, and that I should hesitate to do. The Kadjo is usually painted a red color with Wilgee.

|

| FIG. 149. |

The end of the handle is brought to a sharp point, and in climbing trees, the native, after he has cut a hole for his foot, reaches up as high as he can, sticks the sharp end into the bark, and draws himself up with the hold thus obtained.

If the stone forming the head of a West Australian tomahawk were found anywhere divested of the gum and handle, it is doubtful whether it would be recognised by any one as a work of art. It is ruder in its fashioning, owing principally to the material of which it is composed, than even the rude unrubbed chipped cutting-stones of the Tasmanians. There is much to be learnt from the study of a West Australian tomahawk.

The stone-chisel, Fig. 150, is called by the natives Dow-ak or Dun-ah.[5] It is two feet four inches in length, and about one inch in diameter. The cutting edge projects about two-tenths of an inch, and the stone is securely fastened to the head by gum.

|

| FIG. 150.–(Scale 1/10.) |

In two specimens I possess the stone is pure quartz. Below the lump of gum in which the stone is fixed the implement for the length of an inch and a half is smooth; then there is a hollow, and below that the round stick is grooved longitudinally, so as to enable the mechanic to obtain a firm hold of it. The wood is not heavy, but very hard, and of a dark reddish-brown color. It is used for cutting and shaping boomerangs, shields, clubs, &c., and is employed also in war and in hunting. It is thrown in such a manner as to turn over in its flight, and if it strike a man or a kangaroo, death is certain. It closely resembles the stone chisel or gouge used by the natives of the Grey Ranges (lat. 29° 30’ S., long. 141° 30’ E.), but is a neater if not a better tool than theirs.

The meat-cutter or native knife—Dabba—(Fig. 151)—is made by fixing to a short hard piece of wood (such as that used for spears), with the gum of the xanthorrhœa, fragments of quartz. It looks like a saw, but it is really a knife, and is employed by the natives to cut or jag flesh. This implement is mentioned by the Rev. J. G. Wood, and its uses, I think, have been misunderstood.[6]

|

| FIG. 151. |

The native scoop or spade—Waal-bee—(Fig. 152)—is used for digging roots and holding water. It is made of the outside wood of trees of the eucalyptus tribe, and is formed first by burning it so as to hollow it roughly, and is finished by scraping it with sharp stones and shells, and polishing it with a rasp made of the bark of the Banksia. It is a kind of Tarnuk, but is thinner and better formed, somewhat like a kava bowl without the feet. It is spoon-shaped, and is sixteen inches in length and seven and a half inches in breadth. Mr. Barlee says that this implement is not at all common in West Australia.

|

| FIG. 152. |

The other implements used by the natives are a waddy or club, formed of the same kind of wood as the spears, and a large war club (Weerba). The latter is made of very heavy wood, and is found only amongst the natives of the north-west coast.

Amongst their ordinary implements are bone-needles or skewers, and awls or piercers, also of bone; and they use likewise shells, sand, and rough rasps made of the bark of trees.

Mr. H. Y. L. Brown sent me a ball of twine (Noom-bine) composed of the wool of the opossum, which the natives wrap round the head or the arms or the body. A warrior places a bright-colored feather in this when it is wound round his head; and with his cloak of opossum skins, his spear, throwing-stick, and tomahawk, he is ready for peace or war.

- ↑ Natural History of Man, vol. II., p. 41.

- ↑ See Leange-walert, used for carving by the natives of Victoria.

- ↑ Natural History of Man, vol. I., p. 493.

- ↑ Quoted in Nature, 20th July 1871, p. 230.

- ↑ Mr. Philip Chauncy informs me that the stone-chisel is named Dhabba. The Dow-ak is a stick that is thrown, and is rounded at both ends.

- ↑ Natural History of Man, vol. II., p. 35.