The Aborigines of Victoria/Volume 1/Chapter 16

The stone implements used by uncivilized races are necessarily regarded by archæologists and geologists with great interest. In many parts of Europe there are no traces of the ancient race that once occupied soil now the sites of luxurious cities but such as can be gathered from the stone axes and flint flakes which explorations from time to time discover.

The archæologist, by comparing these implements with others found in neighbouring lands, where they are associated with remains more perishable, but which happily have not altogether gone to decay, gains hints for his guidance in the endeavour to discern something of the life and habits and character of the men who made and used them. And he gains help too by comparing the celts with the instruments now used by savages.

The geologist finds that he has not embraced all that comes within the scope of his labors if he omits to give a distinct place in his system to those drifts where occur chips and flakes of flint and stones bearing the marks of an art which civilized men cannot practise with success.[1]

Whether regarded as objects which, if studied with care, may throw light on the condition of the ancient races who once peopled Europe and Asia long prior to the dawn of civilization, or as helping the geologist to a clearer view of the history of the earth's crust during the most recent period—in his eyes, as compared with former periods, but the records of yesterday's changes; in the eyes of the archæologist, a day so far past that the lapse of time can scarcely be measured by years—:in what way soever these implements are looked at, it cannot be denied that they have a higher significance and a greater value than perhaps any other weapons or tools used by savages.

Knowing full well the importance of the questions involved, I have exerted my best energies to gather together stone implements from all parts of Australia. These will be described, and such information respecting them will be given as, it is hoped, may clear up some points now obscure.

The stone implements used by the natives are as follows:—

(a) Hatchets.

(b) Knives.

(c) Adzes.

(d) Chips of basalt for jagged spears.

(e) Chips of basalt for cutting and scraping skins of animals, &c.

(f) Stones for pounding roots, seeds, &c.

(g) Stones for sharpening spears and hatchets.

(h) Stones for fishing.

(i) Stones used by women in making baskets.

(j) Stones from which ruddle, &c., are obtained.

(k) Sacred stones kept by priests and others.

The hatchets are of various forms, and differ in size and weight; but those of the Victorian natives are nearly all of the same general character. They are provided with wooden handles, as a rule; and the handles are, in Victoria, all of the same shape, and they are fastened to the stone uniformly with cord and gum.[2]

The rocks used for making tomahawks are granite, porphyry, diorite, basalt, lava, metamorphosed sandstone, hard sandstone, dense quartzite resembling hornstone, and granular quartzite. I have seen but few implements made of vein-quartz. The porphyries and diorites are preferred, and nearly all the best tomahawks in my collection are of diorite.

According to Mr. G. H. F. Ulrich, F.G.S., sixty-four tomahawks in my collection may be classed as follows:—

| Greenstone and dense diorite | 18 |

| Aphanite | 13 |

| Nephritic greenstone | 2 |

| Porphyritic rock | 4 |

| Dense black anamesite | 1 |

| Black basalt | 1 |

| Felspathic granite (leptynite) | 1 |

| Metamorphic rock | 14 |

| Quartzite | 8 |

| Hard siliceous sandstone | 2 |

Of those composed of metamorphic rock, four specimens are from Gippsland, two from the River Powlett (on the borders of Gippsland), one from Western Port, one from the Goulburn Valley, three from the Yarra, one from Swan Hill, one from Bacchus Marsh, and one from a locality unknown. It would seem, therefore, that the natives of Gippsland either preferred the hard pebbles of metamorphic rock, which are to be found abundantly in the beds of their streams, or had little commerce with the Western tribes, amongst whom the greenstone axes were common. The natives of Gippsland were always regarded by their neighbours as "wild blacks;" and it is possible that the interchange of weapons and implements, which in early times was quite an important business between the natives of the south and those of the north, was not carried on with the Gippsland people. Other facts well known to the early settlers support this view.

In some places in Victoria there are seen the quarries where in former times the natives broke out the trappean rocks for their hatchets. Large areas are covered with the debris resulting from their labors; and it is stated, on good evidence, that natives from far distant parts were deputed to visit these quarries, and carry away stone for implements. When one or two natives were selected by a distant tribe to make a journey for the purpose of procuring diorite or basalt from such quarries, they carried with them credentials, showing exactly their object. If they faithfully pursued that object, and tarried no longer in any place than was necessary, they appear to have been allowed to proceed without molestation, and to have been treated as guests—not always as welcome guests, but with such protection as the host gives to those that, perhaps unwillingly, he entertains. If, however, they interfered in the quarrels of any tribe, violated any custom, or seemed not really anxious to hasten the journey, they were treated as enemies, and sometimes pursued and killed.

It is not to be supposed, however, that the native tribes of Victoria within the boundaries of whose lands there was neither diorite nor basalt were altogether dependent on their neighbours for supplies of stone. Many of them made hatchets of the rocks which they broke out of sandstone quarries, and, though far inferior to those made of trappean rocks, were nevertheless effective on ordinary occasions.

It is certain that the natives often bartered skins, spears, shields, and other things for stone.

Hatchets made of diorite are possessed by tribes occupying the wide Tertiaries which stretch north of the River Murray, where for many miles no rock is to be seen. These, or the material of which they are made, could have been obtained only by favor or by barter, or from enemies captured or slain in battle. Their young men may have been permitted to visit the quarries in the south or east, and to take away stone, but it is at least probable that they paid something for the privilege.[3]

In the extensive tracts occupied by sands and clays, and in which no stone fit for tools is to be obtained, the natives must have cast wistful eyes towards the more favored localities where all the best materials for stone implements are to be found; and one may conjecture how they would humble themselves and entreat those who could supply them with good materials. Their best feathers, their best woods, their favorite skins, and even their wives and daughters, would be offered in exchange for the basalts and diorites which occur on and in the neighbourhood of the Great Range.

The stone tomahawk is all-important to the native, and in some districts he could scarcely maintain existence without it.

The natives of Victoria, according to the information I have obtained, appear to have used the one-edged tomahawk exclusively.[4] I have not found a single example of the two-edged tomahawk in Victoria. Their Merring, Karr-geing, Kal-baling-elarek, or Kul-bul-en-ur-uk, in this respect, and also in its being ground and sharpened, differs from the tomahawk of the West Australian natives, which is made of granular quartzose granite or of quartz-rock, and fashioned by repeated blows until the desired shape is attained. It will be seen, too, that the wooden handle is different.

The opinion entertained by many archaeologists that ground and polished tools belong to the Neolithic period, and those made by successive blows to the Palæolithic period, is reasonable enough, and probably, as regards some extinct races, true; but we have here in Australia, on the east, highly-polished implements, and on the west, in districts where rocks susceptible of polish are not to be obtained, rude stone axes made by a succession of blows. There is no method by which we can distinguish a difference of period if we examine stone implements. In the hands of a native of Australia you see a highly-polished stone axe of diorite and a knife or adze of granular quartzite or porcelainite made by blows, and which could not be easily ground by any contrivance available to him. Some of the axes are merely large pebbles, sharpened and polished at one end; others are evidently from a quarry, and made by blows given with skill and precision, so as to knock off flakes one by one until a scalpriform implement was obtained. The end of the stone was ground, the handle fitted to it, and the axe was then ready for use. Some of the axes made of sandstone appear to have been formed by grinding only.

In addition to the ordinary tomahawk, the natives of some parts of Victoria had large stone axes made of basaltic rock, which were used for splitting trees. One in my possession is eight inches in length, five inches in breadth, and two inches in thickness. It weighs four pounds eight and a half ounces. Implements of this size are very rare. One was found in trenching a garden at Ballarat by Mr. Samuel Hutson, on the 16th March 1864. It is described and figured in Dicker's Mining Record. Its length was eight inches, its largest diameter a little under four inches, and its weight about five pounds avoirdupois. Like that in my collection, it was of basaltic rock, and grooved for receiving the wooden handle.

It is scarcely possible to disturb any large area of the natural surface in Victoria without lighting on some of these weapons. In ploughing the ground they are often found and cast aside. In a small garden on the banks of the River Powlett in the County of Mornington, on the edge of the dense forest, four tomahawks were discovered; and indeed many of the old implements in my collection were got in digging or ploughing. And all over the country flakes of black basalt used for cleaning skins and for fitting into spear-heads are abundant. I have in some places collected in half an hour, from an old Mirrn-yong or midden near the sea-coast, as many small flakes (broken off in making tomahawks) as would fill a pint measure. Mr. Geo. H. F. Ulrich found a great number when engaged in making geological surveys. He says:—

"During the prosecution of the Geological Survey over the Castlemaine, Yandoit, and Mount Tarrangower districts, my attention was frequently attracted by the occurrence on the surface of small angular chips of a dense black rock that very much resembled Lydian stone, but on closer examination proved to be basalt.[5] The only place where this peculiar dense variety of basalt has as yet been observed in situ is near the Little Coliban River, about seven miles west of Kyneton, and it forms there apparently irregular thin layers and disconnected patches in the common grey vesicular doleritic basalt of the district.[6]

Concerning the mode of occurrence of the chips—I observed them most abundantly on the slopes of softly-rising hills, in some places several inches beneath the surface, but also on the surface and in crevices of outcropping rocks on the tops of the highest Silurian ranges in the Fryer's Creek, Yandoit, Mount Tarrangower, and other districts—quite into the dense forest. In fact they appear so generally distributed that any one, I believe, whose attention has been directed to them, could not fail to find one or more or several of these chips on any route he might choose through the ranges mentioned. Their mode of transport to such heights and distances, exceeding thirty miles from the Little Coliban River, was an interesting puzzle to me for a long time. The wild idea of considering them as having been carried over the country in consequence of submersion and tilting of the strata beneath the sea first presented itself, and was, of course, soon discarded; and the proposition for some time gained favor that they might have been transported and scattered by emus, whose proclivity for swallowing hard angular bodies to aid digestion is well known. However, the finding near the Muckleford Creek of a pretty large piece of the rock, and near it a number of smaller ones, all with at least one, and some with two sharp knife-like edges, solved the riddle, in proving conclusively that human hands had been at work there.

No doubt these chips have, during past generations, been carried about, and lost or thrown away by the Aboriginals of the country, who used them instead of knives for fashioning their wooden weapons, skinning opossums, and other work requiring cutting and scraping."

Any one who will take the trouble to examine the country as Mr. Ulrich has done will corroborate the statements made by him. Most of the flakes and fragments are such as were struck off by the Aboriginals when shaping their tomahawks; but not a few were made expressly for scraping the skins of beasts taken in the chase, for fitting into the heads of spears, and for knives or adzes.

When Mr. Ulrich was examining the mineral districts of South Australia, he observed that chips and flakes of basalt were to be found in almost every locality. He sent me one—a chip struck off in forming a tomahawk, as suggested by the natives to whom I submitted it for examination—which he picked up on a low rise twelve miles north of Pekina, about three hundred miles north of Adelaide. Broken tomahawks, broken adzes, chips and flakes of basalt, and near the coast old Mirrn-yong heaps, which for ages have been covered with drift-sand, are from time to time discovered. All these show that the Aboriginals, living in exactly the same state as they were found when Australia was first discovered by Europeans, have been for periods incalculable the possessors of the soil.[7]

|

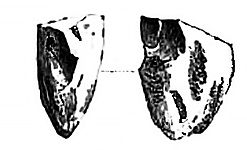

| FIG. 175. (Longitudinal section at right-angles to the cutting edge.) |

Mr. E. J. Dunn made a large and valuable collection of stone implements when engaged in geological researches. He says:—"When connected with the Geological Survey at Maldon, Clunes, and other places, I took great interest in the relics of the blacks, and spent many days in hunting about the low ranges for tomahawks, in which pursuit I was moderately successful. I have between forty and fifty broken and whole ones, several sharpening-stones, and some pounds weight of chips of a great variety of rocks, though black basalt predominates. The tomahawks are nearly all of greenstone; the others are of porphyry or metamorphic sandstone. Nine- tenths of the broken heads have the shape shown in Fig. 175. When no stone was available in the immediate neighbourhood fig. 175. of their haunts, they carried thither pieces of a few pounds weight for many miles."

Mr. Reginald A. F. Murray, a Geological Surveyor employed by the Government, informs me that he has found stones in the Mirrn-yong heaps near Shelford. The stones were basalt, and those in some ovens on Silurian ground had been carried thither by the blacks, who had evidently recognised the superior heat-enduring and heat-retaining properties of that rock. Mr. Etheridge, formerly of the Geological Survey, noticed the same facts in the McIvor district, and stated that he saw there, in ovens, fragments of basalt that must have been carried several miles.

The stone implements used by the natives of Tasmania are described in another place. From information most kindly communicated by Ronald Gunn, Esq., F.R.S., Dr. Agnew, the Honorary Secretary of the Royal Society of Tasmania, and the Rev. Mr. Kane, it appears that the natives of that island had no stone implements that can be regarded as tomahawks. They used stones roughly shaped by blows, so as to get a cutting edge, for skinning animals, cleaning skins, shaping clubs, &c.; but they were not fastened to wooden handles, as the Australian axes are.

It will be seen, on referring to the detailed descriptions of the Australian axes, that many of them are very beautiful implements, well-formed, well-balanced, and with cutting edges of equal finely-executed curves. They indeed, in the best examples, greatly resemble, in the form of the cutting edge, the American axe, which is considered by woodmen the best implement of this kind that has yet been invented.

It is remarkable that no stone hatchet, chip of basalt, or stone knife has been found anywhere in Victoria except on the surface of the ground or a few inches beneath the surface. It is true that fragments of tomahawks and bone-needles have been dug out of Mirrn-yong heaps on the sea-coast, covered wholly or partially by blown sand; but though some hundreds of square miles of alluvia have been turned over in mining for gold, not a trace of any work of human hands has been discovered. Some of the drifts are not more than three or four feet in thickness (from the surface to the bed-rock), and the fact that no Aboriginal implement, no bone belonging to man, has been met with, is startling and perplexing.

Within quite recent periods—at various times since the colony was occupied by the white race—large rivers, like the Snowy River in Gippsland, have in some places changed their beds; creeks have cut through bends of a horseshoe shape, and rivulets have made for themselves new channels. Such old beds and channels in many parts have been completely dug over by gold-miners, and the detritus and debris have been washed; but, as far as I know, there has not been recorded any discovery of native implements. In much older gravels, clays, and sands, underlying Recent Volcanic rocks, where occur fossil fruits belonging to genera now found only in the northern parts of Australia, the miner has carried his explorations; but nothing belonging to man has been seen. More recent deposits, in which are imbedded trunks of trees, and where the cones of the Banksia, leaves of several species of eucalypts, and remains of marsupials, are of common occurrence, are likewise barren. The tracts where, over a large area, volcanic ash, some thirty or forty feet in thickness, overlies a grass-clad surface once trod by the native dog, and on which his bones are found, retain no trace of the native. Even the caves which have been explored exhibit no other than very recent evidences of the existence of the race. All this is the more extraordinary, when we take into consideration the fact, already stated, that old tomahawks, chips of basalt, &c., are widely scattered over the surface of every part of Australia that has yet been visited by Europeans.

If only small portions of the alluvia in Victoria had been excavated—if the country had not been occupied for twenty years by many thousands of miners, who have washed the gravels down to the bed-rock in innumerable shallow gullies—the non-discovery of relics might have been easily accounted for; but in this country the spots most likely to conceal them have been laid bare.[8]

Dr. Day, of Geelong, sent me, through Mr. J. A. Panton, a collection of bone-needles found in the garden of Mr. Currie, near Camperdown. They are evidently very ancient, and it was supposed at first that they had been obtained from some one of the younger Tertiaries; but on making enquiries, Dr. Day ascertained that they had been uncovered by Mr. Currie's gardener when trenching, and that with them were numerous human skulls and other bones—proving that the spot had been an ancient burial-place of one of the Western tribes.

Hatchets.

|

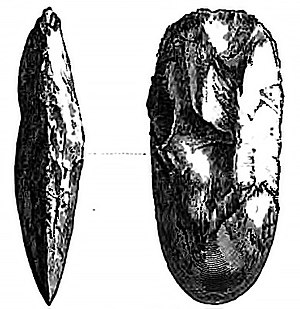

| FIG. 176.—(Scale ¼.) |

The tomahawk shown in Fig. 176 (a and b) is that commonly used by the Aborigines of the Yarra. The stone is a dense quartzite, resembling hornstone, with a splintery fracture. It appears to have been shaped by well-directed blows. It has a keen, well-polished cutting edge. The stone is five inches in length, two in breadth, and about three-quarters of an inch in thickness. The wooden handle is fifteen inches in length, and is well and firmly fixed to the stone. Though the gum used in fixing the head to the handle is now cracked and crumbling, the union is perfect, the wood having been originally well heated and moistened and made to grasp the stone closely. The handle, near the head, is strongly bound with the fibres of the stringybark. The weight of this implement is thirteen and a half ounces.

|

| FIG. 177.—(Scale ¼.) |

In Fig. 177 is shown a well-made tomahawk from Lake Tyers in Gippsland. The stone is greenstone (dense diorite), of very even texture, and appears to have been taken nearly in the form in which it is seen now from a river-bed. The cutting edge has been ground and polished, but in other respects it has not been altered. It is six inches in length, two and a half inches in breadth, and one inch in thickness. The wooden handle is fifteen inches in length; and the weight of the whole is one pound five and a quarter ounces. As the handle could not be made to embrace the stone so closely as to prevent some movement, pieces of stringybark have been inserted between the wood and the stone, and near the head the handle is bound with the sinews of some animal. No gum was used in effecting a junction.

|

| FIG. 178.—(Scale ¼.) |

Another tomahawk from Lake Tyers (Fig. 178) is also an excellent implement. The stone is a hard metamorphic schist, very dense and heavy. It is more or less polished all over the surface, and it is now difficult to say whether it was found originally nearly in the shape in which we see it or was wrought into form by hand. It has a good cutting edge, and the curves are as good as those of the best American axes. It is six and a half inches in length, three and a quarter inches in breadth at the broadest part, and nearly one inch and a quarter in thickness. The wooden handle is firmly fixed to the stone without gum or stringybark wedges. The weight is one pound twelve and a half ounces.

A Victorian tomahawk, exactly like many of those used in the north-western parts of New South Wales and in Queensland, is shown in Fig. 179. The wooden handle is stout, and is fastened with gum and cord. The part grasped with the hand is also tied for better security.

|

| FIG. 179.—(Scale ¼.) |

|

| FIG. 180.—(Scale ¼.) |

Fig. 180 represents a stone tomahawk from the Burdekin River, North-Eastern Australia. It was in the possession of the late Mr. Matthew Hervey, and is an excellent, well-made implement, worthy of preservation. The stone is an altered slate. It has been made by striking off flakes; and the cutting edge is beautifully formed and highly polished. The head where the handle grasps it is covered with a gum obtained perhaps from the xanthorrhœa, and the junction is perfect. The wooden handle has been split from the strong runner of some creeping plant. It is tough, very strong, and somewhat elastic. The cord which binds the two parts of the handle near the head is made of fibres obtained from the root of a plant resembling the lily, and is neatly and well twisted. This implement is, I believe, named Karra-gain by the natives of the Burdekin. This is one of the best native tomahawks I have seen. It was obtained from a wild tribe quite unacquainted with the arts of Europeans.

A large and rather remarkakle tomahawk (Fig. 181) was brought from the Munara district by Mr. J. A. Panton. The stone is a hard, very dense, dark-green aphanite (a fine-grained variety of diabase). It is beautifully polished quite up to the handle. The breadth is four inches and three-quarters, the length is five inches, and the thickness about an inch and a half. The handle is apparently of light wood, coarsely fashioned; and the twisted cord with which it is tied is made of the fibres of some bulbous root. The gum is hard, and resembles that got from the xanthorrhœa. It is heavy and clumsy, but the grinding and polishing of the stone must have given much trouble to the artist. The weight of the implement is two pounds four and a quarter ounces. It is probable that it was used for splitting large trees; and in handling it and proving its strength, one is justified in supposing that it had been made for rough work of this kind, and not for cutting holes in climbing.

|

| FIG. 181.–(Scale ¼.) |

|

| FIG. 182.–(Scale ⅛.) |

A very large stone implement (Fig. 182), in the possession of Mr. W. E. Stanbridge, is one of the most remarkable of all the stone weapons yet found in Victoria. It was discovered in a field at Daylesford. It is supposed to have been used for digging roots, and in sinking holes to get at the wombat. It was made by striking off flakes; but the cutting part is ground and polished. It appears to be a piece of metamorphosed sandstone. It is about fourteen inches in length, five inches in breadth, and rather more than one inch and three-quarters in thickness.

|

| FIG. 183.–(Scale ¼.) |

The tomahawks in my collection which have been found at various times in the soil of gardens, in fields when they have been ploughed, or in Mirrn-yong heaps, or on the surface of the ground, or in the beds of streams, are of course without handles. Many of them, as will be seen from the figures and descriptions, are remarkably well made; and the differences in form and mode of manufacture are so great as to make one regard them with much interest. Only those which illustrate most completely the art of this people are figured; others are described in words only.

One large axe-head in my collection (Fig. 183) was dug out of a Mirrn-yong heap at Lake Condah by Mr. John Green. Its weight is four pounds eight and a half ounces. Its length is eight inches, its breadth five inches, and its thickness rather more than two inches. It is grooved so as to admit of the wooden handle being firmly attached to it. It is so much decomposed on the surface as to be easily scratched with the nail, and must have lain covered by the charcoal and the soil of the Mirrn-yong heap for an immense period of time. The thickness of the decomposed outer layer (clay ironstone) is about one-sixteenth of an inch; and when a small portion of this was removed, the rock proved to be a basalt or greenstone. Wye-wye-a-nine, a native of the Murray, informs me that axes of this kind were used for splitting open large trees, so as to get out opossums from the hollows, when it was impossible to reach them in any other way. The name of the implement is Pur-ut-three. Fitted with a suitable handle, the weight would not be less than six or seven pounds. This is a rare form of the tomahawk, and the specimen here figured is undoubtedly very ancient.

The stone axe (Fig. 184) from Coranderrk looks like a pebble from a brook. It seems to have been formed, not by striking off flakes, but by notching it. It is a hard, dense, black greenstone (like aphanite), and how it was notched I cannot imagine. Its weight is one pound one and a half ounces. Its length is six inches and a half, its breadth two inches and a quarter, and its thickness one inch and a half. In section it is lenticular. The cutting edge has symmetrical curves, and the lower part is highly polished. There is a hollow on one side of the upper part of the stone, made probably for attaching the handle with security. This is in all respects an implement of a highly-interesting character. It is in excellent preservation, and the edge is very sharp.

|

|

|

| FIG. 184.—(Scale ¼.) | FIG. 185.—(Scale ¼.) | FIG. 186.—(Scale ¼.) |

The implement from Lake Tyers (Fig. 185) is a piece of hard granular metamorphic sandstone. Its length is six inches and a half, its breadth two inches and a half, and its thickness one inch and a quarter. Its surfaces are flat, but at the cutting edge it has the usual curves. Its weight is one pound two and a quarter ounces. It is evidently a very old implement. When this instrument was shown to Wye-wye-a-nine, he said it was Tal-kook—very good—and one of the best in the collection.

Another axe from Lake Tyers (Fig. 186) is a hard, nearly black, metamorphic sandstone, from the vicinity, probably, of some mass of granite. It weighs one pound, and is six iuches in length, two inches and a half in breadth, and one inch in thickness. It is a clumsy, ill-made weapon. The cutting edge is roughly formed and not symmetrical, though highly polished. It appears to have been a water-worn fragment obtained from a river-bed.

A mutilated tomahawk, with a beautifully-curved cutting edge (Fig. 187), was obtained by Major Couchman when engaged in surveying Pental Island, on the River Murray. It is a fine granular—nearly dense—quartzite.

A small tomahawk obtained from the Yarra tribe (Fig. 188) is rudely fashioned from a block by striking off flakes. The cutting part is well ground and polished, and when fitted with a handle it must have been a handy and useful instrument. The rock is aphanite, and the axe is only three inches and a quarter in length. Its weight is seven and a quarter ounces.

|

|

|

| FIG. 187.—(Scale ¼.) | FIG. 188.—(Scale ¼.) | FIG. 189.—(Scale ¼.) |

A very small greenstone axe, found in the neighbourhood of Kilmore (Fig. 189), has a polished cutting edge; but the edge itself is much chipped and jagged, perhaps because the grinding and polishing were never completed, or because of rough usage after completion. Its weight is three ounces. Its length is only two inches and a half, its breadth in the broadest part less than two inches, and its thickness no more than three quarters of an inch. This is the smallest tomahawk in the collection.

In Fig. 190 is shown a tomahawk of greenstone (resembling serpentine), roughly shaped by chipping, and partly ground in one part. It was found in the neighbourhood of the quarry at Lancefield, where stone suitable for these implements was in former times dug out by the natives. It appears to have been partly formed, and then, being found unsuitable, thrown away by the natives. Its weight is ten and three-quarter ounces. It is interesting as showing the form which these implements presented after chipping, and before being ground and polished, and affords a notion of the immense labor the natives must have bestowed in giving to a roughly-chipped axe the proper shape and polish. To shape this fragment into a good axe would, without mechanical appliances, require the hard labor of many days.

|

|

| FIG. 190.—(Scale ¼.) | FIG. 191.—(Scale ¼.) |

Another roughly-shaped axe (Fig. 191) was found in the same locality. No attempt has been made to grind or polish it. The upper part appears to have been accidentally broken off, probably when chipping it. The material is a metamorphic siliceous sandstone (knotted sandstone).

Fragments of highly-polished stone axes, such as are commonly found in the low ranges running down towards creeks and in scrubby lands, are shown in Figs. 192, 193, and 194. These have been struck off when axes have been used with violence, or have accidentally struck a rock when a blow has been aimed at a branch lying on the ground, or at some animal when the native has failed to capture it. Great numbers of such fragments are found in nearly all parts of the colony. The stones are greenstone, of fine, even texture. The largest fragment is not more than two inches in length, and one inch and a half in breadth. These are altogether different from the flakes struck off in forming tomahawks, which are still more numerous.

|

|

|

| FIGS. 192, | 193, | 194. |

| (Scale ¼.) |

A very thin axe, of dense siliceous metamorphic rock, about three inches and a half in length, and two inches and a half in breadth, was presented to me by Mr. John Saunders, of Bacchus Marsh. He states that it was found in a native oven (Mirrn-yong), on the banks of the River Werribee, by Mr. C. Mahoney, about twenty-four years ago. There were found also in the same heap some human bones, which were recognised as part of the skull and the lower-jaw of an Aboriginal, and with these remains were bones of the kangaroo, &c. The implement has a sharp cutting edge, and when fitted with a handle must have been a very good instrument, and useful in cutting holes in the bark when climbing trees, and for shaping shields, spears, &c. It is a very ancient instrument, though not nearly so old as some others in my collection.

A beautiful axe, of dense aphanite, made by striking off flakes, was given to me by Mr. Alfred Chenery, of Delatite. It is four inches in length, an inch and a half in breadth, and rather more than an inch in thickness. The curves of the cutting edge are symmetrical and highly polished. There is no implement in my collection which more completely exhibits the skill of the Aborigines than this; but as another equally good and of the same character is figured in this work, it is unnecessary to give a drawing of it. It is a light and very good tomahawk.

A tomahawk of aphanite greenstone, in part slightly fine granular, rudely formed, and with an unsymmetrical cutting edge, was presented by the same gentleman. It was found near the River Delatite, and belonged probably to the men of the same tribe who had fashioned the axe above described.

Mr. Reginald A. F. Murray, one of the Geological Surveyors employed by the Department of Mines, found near Alexandra, in the same district in which Mr. Alfred Chenery's tomahawks were discovered, a small axe of very fine, dense, metamorphic micaceous rock, much resembling a variety of gneiss called cornubianite. It is pitted, owing to the Fahlunitic minerals on the surface having decomposed. The edge is not sharp, but an effort has been made to polish the whole of the surface of it. It is a fragment; but it shows that the natives experimented with different stones, and, when necessities were great, took those that were most easily to be got. Mr. Murray says that the fragment was probably broken off during use, and that it must have been carried many miles, as no stone of a similar character is found in the district.

An axe of an unusual form (Fig. 195) was dug out of a garden at Winchelsea. It is much weathered and decomposed on the surface, and is exactly like a piece of Mesozoic sandstone, but on taking off a small portion of the crust it is seen to be a bluish-grey dioritic rock. It is polished all over, and must at one time have had a very keen cutting edge. It is deeply grooved in the place to be grasped by the wooden handle, and for greater security there is a projecting point or shoulder on that side where the wooden handle would be fastened with sinews. It is four inches in length, three inches and three-quarters in breadth, and one inch and three-quarters in thickness. On one side the groove is highly polished by the friction of the wooden handle. It must have lain in the soil a very long time. The whole surface is decomposed to the depth of one-sixteenth of an inch. Its weight is fourteen ounces.

A tomahawk, in shape somewhat like that shown in Fig. 195, but not grooved for the handle, and of a smaller size, was found near Geelong. It is a hard, dense, nearly black, quartzite, resembling greenstone. The curved surfaces of the cutting edge are good, and highly polished. It is three inches in length, and rather more than two in breadth. It is one inch and a half in thickness, and weighs eight ounces and a half.

|

| |

| FIG. 195.—(Scale ⅓.) | FIG. 196.—(Scale ⅓.) |

Mr. Alfred Howitt sent me a well-formed axe (Fig. 196), which was found in cutting a race on the Dargo River. Mr. Browne, the claimholder, who discovered this and another tomahawk in making excavations for the race, informed Mr. Howitt that they were buried about a foot deep in the soil and fine gravel. The locality is the crest of a steep spur immediately below a capping of volcanic rock, and a dense scrub covers the whole place. It is not possible to form an estimate of the age of the tomahawks, but it is certain that they must be very ancient. The implement is five inches in length, two inches and a half in breadth, and nearly two inches in thickness. The cutting edge, like that of others of the best kind, exhibits beautiful curves, and it is now so sharp as to cut hard wood easily. It looks like a water-worn stone from a river-bed, and has not been altered at all except at the cutting edge, which is ground and highly polished. The stone resembles hornfels, and is, in all probability, a water-worn fragment of metamorphic rock from the near neighbourhood of granite. This axe was much admired by Wye-wye-a-nine, who, when he saw it, said—Tal-kook—very good. Its weight is one pound three ounces and a quarter; and, when fitted with a good handle, it must have been a most excellent implement.

|

| FIG. 197.–(Scale ⅓.) |

A large stone tomahawk, in the possession of Mr. G. C. Darbyshire, which he has permitted me to examine and figure for this work (Fig. 197), is, it is believed, from the Darling district. It has been formed by striking off flakes, and the skill and precision with which this has been done cannot be properly represented by any drawing. It is a beautiful implement, with a highly-polished and very sharp cutting edge. The gum used in fixing the handle still adheres to it, and the stone is not in the least decomposed in any part. The material is a dense dark-green quartzite, resembling hornstone. It is seven inches in length, three inches and a quarter in breadth, and the greatest thickness is one inch and a half. It weighs one pound nine ounces and three-quarters. Though it may be said that this axe is roughly hewn, the blows have been given with so much precision as to excite surprise, having regard to the material of which it is composed. With all the help of good tools, I question whether any European could make a better axe if he had a rough block of quartzite given to him for the experiment.

When I was at Mr. Fehan's out-station on the River Powlett, I asked the manager, Mr. Bees, whether any stone implements had been found in the district, and on his informing me that some had been turned up in digging the garden (a piece of land about a quarter of an acre in extent, and having a steep slope towards the river), I wrote to Mr. Fehan asking him to procure, if possible, any specimens of this kind. He replied promptly and courteously, and sent me five stone axes, all of which, I understand, had been found in the garden. The area now known as the Wild Cattle Run must have been, in past times, a favorite resort of the natives. It was probably debatable land, and certainly, if the oldest accounts given by the natives are to be trusted, the scene of many battles between the Western Port blacks and the tribes of South-Western Gippsland. In these encounters it is not unlikely that implements were often lost, but still it is remarkable that so many as five stone axes should have been found in digging up the surface of a small area.

One of the axes is evidently very ancient. It has been split in using it, and then thrown away. It has lain so long in the ground that it is now pitted all over, both on the polished side and on that which has been broken. It is a piece of metamorphic nodular schist, and the Fahlunitic minerals are decomposed and washed out. The siliceous base alone is left on the surface.

Another, of felsite porphyry, is also ancient. It is almost perfect. A small piece is broken off the cutting edge.

A flat, nearly square axe of very fine granular dense diorite greenstone has a good cutting edge, but the grinding extends over a surface no more than half an inch on each side. This implement is altogether different from the hatchets now used.

The fourth—of metamorphic sandstone, like quartzite—has been formed by striking off flakes. It is well ground, has a good edge, and is evidently more recent than any of the others found in the garden.

The fifth—of dense quartzite—is an excellent implement, and from the appearance of the upper part, where the wooden handle was fixed, has probably been disused but for a comparatively short time. Its weight is one pound nine and three-quarter ounces—nearly double the weight of any of the others.

A very small tomahawk, of fine-grained dense siliceous metamorphic sandstone, was found by one of Mr. Robert Anderson's servants in the "Cups," at Cape Schanck. It has a remarkably good edge. It is one of the best axes in my collection.

Three small, neatly made axes, with well-polished cutting edges, sent to me by the Honorable Theodotus J. Sumner, M.L.C., were found near Tyabb, on the western shore of Western Port. One is of aphanite, and two of metamorphic rock.

One sent from Coranderrk is of aphanite—small, ill-shaped, but with a keen edge; and another, of very fine-grained siliceous sandstone, is triangular, and when fitted with a handle must have been a very useful implement.

At Green Hills, near Mooroolbark, Mr. William Turner found two axes—one somewhat flat, and made by striking off flakes, but with the usual well-ground cutting edge; and another nearly round, and with a narrow sharp edge. The latter is a piece of hard, dense, tough metamorphic rock.

The Honorable W. A. C. à'Beckett has sent me a small axe, found near Cranbourne. It is a dense aphanite, with, in places, a porphyritic texture. It has a cutting edge, and one side is flat and beautifully polished. One cannot say why this side was polished. The stone may have been used for grinding and polishing other axes. It is the only specimen of the kind I have seen.

Of the axes found near Melbourne I possess only two specimens. One—a very neatly-formed implement—was found in a paddock near my house. It is composed of fine-grained laminated felspathic granite, resembling leptynite or white stone. The edge is highly polished and very sharp. The other is unfinished. I picked it up many years ago in the bed of the Moonee Ponds (a creek). It is a fragment of metamorphic sandstone, chipped and shaped, but not ground.

I have obtained from Mr. Oct. Lloyd a small axe of very fine-grained hard greenstone, which he found near the Red Bluff at Brighton. It is a moderately good axe.

From the Mirrn-yong heaps on the shores of Cape Otway, Mr. Reginald A. F. Murray has sent me, together with other Aboriginal implements, two ancient stone axes. One, a fragment—much discolored, by having lain a great length of time in a mass of charcoal, burnt bones, and the like—is of black basalt. It is broken and disfigured, but one side of the cutting edge is well polished. The other—evidently, from its condition, from a Mirrn-yong heap, being blackened with charcoal—was found in a cart-rut. It is a good weapon, and the edge is very sharp. One side is nearly flat and slightly polished; the other side is convex. It is a dense black anamesite—intermediate between dolerite and basalt. Where the material for such axes was obtained one can but conjecture.

Mr. Geo. C. Darbyshire found at Audley, near Hamilton, in the western part of Victoria, a well-shaped, chipped, and partially ground axe of aphanite porphyry (felspar porphyrite). It is an unfinished implement, of a material rarely used.

In Section 3, Yarram Yarram, near the Jack Rivulet, in Gippsland, and on the site of an old native camp, Mr. John Ferres found an axe of aphanite. It is a rude hatchet with a heavy head. It has been made by chipping. The cutting edge is highly polished, but not sharp.

In the excavated gravel, near the site of the dam at Malmsbury, Mr. Davies found an axe of dense greenstone, with a ground cutting edge. The upper part is broken off. It is similar in shape to the axes used by the Loddon tribes. It is evidently an old implement, thrown away when it had become useless. One side is much flatter than the other, and it would appear to have been used in shaping and grinding other axes.

A large hatchet, weighing one pound seven and three-quarter ounces, was sent to me by Mr. John Filson, of Flemington. It was found at Kerang, on the Lower Loddon. It is formed of dense, hard, tough, nephritic greenstone. Its length is five and a half inches, and its breadth two and three-quarter inches. The corners are not rounded. The cutting edge is quite straight and well polished, and as keen as when it was finished. It is not as well shaped, but is as good an implement as any in my collection. The curves on each side of the straight cutting edge are not surpassed by the best American tools.

Mr. Clement Johnstone, Mining Surveyor, sent me what appears to be only a fragment of a stone axe of porphyry from Albury, on the River Murray. It has a well-rounded and exceedingly sharp edge. The polished surface at the edge is nowhere more than two-tenths of an inch in extent, and the greatest thickness of the stone is only three-tenths of an inch. One would suppose, at first sight, that the sides had been split off, but it may be a rare form adapted to some particular purpose.

Another axe—from Chiltern, a little lower down on the River Murray—was found by Mr. R. Arrowsmith, Mining Surveyor. It is, like that just described, a hard, dense, nearly black, siliceous porphyry. It is six inches in length, two inches and a quarter in breadth, and about six inches and a quarter in circumference. It is a very heavy and beautifully-finished implement. The polishing extends more than two inches from the cutting edge on each side, and the curves are symmetrical. Its weight is one pound seven and a quarter ounces.

Mr. Suetonius H. Officer, of Murray Downs, has collected three axes on the Lower Murray. One is of dense greenstone, one of porphyritic rock, and the third a quartzite with felspar enclosed—a kind of felspathic granite. They are all good axes, with excellent cutting edges. The axe of porphyritic rock is six inches in length and two inches in breadth. It has a sharp curved cutting edge, no more than an inch and a quarter in breadth. This is apparently a very old weapon, and somewhat resembles the axe found by Mr. Arrowsmith.

Mr. Reginald A. F. Murray found on the banks of the River Leigh a fragment of an axe, of which little more than the polished cutting edge remains, greatly resembling in form the stone axes used in the western parts of Queensland. It is a piece of greenstone.

Lieut.-Col. Champ has added to my collection a small well-finished axe of black siliceous porphyry, also from the Leigh, which has a very fine edge; and a portion of an ancient tomahawk, showing only the half of the cutting edge, of very hard metamorphic rock.

Mr. John Lynch, the Mining Surveyor at Smythesdale, obtained from a miner at Bottle Hill, near Carngham, a very well-made tomahawk of aphanite, which was found in a puddling machine. It had been lying, as suggested by Mr. Lynch, on or very near the surface of the ground where the wash-dirt was deposited, and had been thrown with the wash-dirt into the machine. The cutting edge, less than an inch in breadth, is well polished, and very sharp.

Two axes from the River Darling are interesting. One, of very dense, tough, granular greenstone, resembles that obtained by Mr. Panton in the Munara district.—(Fig. 181.) It is five inches and a half in length, four inches in breadth, and in the middle about one inch and a half in thickness. It weighs one pound fifteen ounces. It has a very fine and rather pointed cutting edge. It was found by Mr. William Hoffmann.

The other, brought to Victoria by Mr. Darbyshire, is of prase-like quartzite, very tough and hard, and with a good edge. The edge is highly polished, but otherwise it is rudely formed. It is a small axe, not larger than those commonly used in Victoria.

Mr. Molesworth Greene has allowed me to make a fac-simile of an axe of great size, which was lately brought from the Paroo, in Queensland, by Mr. A. Sullivan. It is eight inches in length, six inches in breadth in the broadest part, and two inches in thickness. It is an oval-shaped weapon, highly finished, and, for a great extent around the cutting edge, well polished. The wooden handle is not attached, but the place of attachment is apparent, and on one side there is a mass of gum adhering to it. It is as large and as heavy as the implement (Fig. 183) found at Lake Condah.

Another tomahawk, of dense greenstone, shaped somewhat like the American axes made by Collins and Co., was obtained by Mr. A. Sullivan on the Bulloo Downs, Paroo. From the appearance of the surface, one would suppose that it had been buried in the earth for a long period.

A curious axe, sent to me by Mr. J. McDonnell, of Brisbane, Queensland, is an example of those used in the Moreton Bay district. It is a rude rhomboidal block, evidently occurring naturally. It is five inches in length, two and three-quarters in breadth, and an inch and a half in thickness. It is of hard, dense greenstone. It has an irregular, ill-formed cutting edge, and an attempt has been made to polish the whole surface of the stone.

There are four other axes in my collection very similar to those already described. One with the wooden handle attached by sinews and gum is, I believe, from the Far North. It is exactly like the tomahawks used by the men of the Yarra. One, of aphanite, is not finished, being polished only in one or two places, but is instructive as showing at what stage the polishing was begun. It is apparent that the axe was, in the first instance, pretty well formed by chipping; but the labor of reducing the uneven surface to smoothness and polish, with symmetrical curves, must have been very great. Another imperfect axe, of greenstone, shows in like manner the method employed by the Aboriginal artist. The last is a fragment of an axe that probably had been broken in using it.

I have to add to these descriptions an account of what is believed to be a spurious tomahawk, but which is so like in form to many that are figured in this work as to have deceived some who are well acquainted with Aboriginal stone implements. It is an oval-shaped piece of basalt, picked up by me from a cart-rut, where it may have been rubbed by the wheels of passing vehicles. I cannot say whether or not it was formed by hand; but the character of the rock, and the grinding, seem to favor the view that it is a fragment shaped by accident in the manner suggested. There are doubts respecting this stone; and the fact that it is not easy to determine its character should teach caution to those who are inclined too hastily to ascribe to accident that which is really the work of human hands; and to others who, without proper consideration, regard as the work of extinct races stones whose form is due to the operation of unknown forces.

|

| FIG. 198.–(Scale ½.) |

The axe Fig. 198 was in the possession of the late Mr. A. F. A. Greeves; and it is figured because it is in itself a remarkable implement, and contrasts with the axes made by the natives of Australia. This axe, of a mineral resembling jade, well-shaped, with a good cutting edge, but not highly polished, was picked up many years ago in Pitcairn's Island. It is not known whether it is a relic of a colored race that once peopled that island, or whether it was taken to the island by the Tahitians who accompanied the mutineers, or was fashioned by some of the mutineers who reached the island in 1789. It is worthy of preservation. At the present time the history of our species is being eagerly investigated by learned men, and this implement may prove of value: if an ancient axe, it is of surpassing interest; if made by the mutineers, an instance of the recurrence to habits of the uncivilized which teaches an important lesson.

Getting Stone for Tomahawks, etc.

Mr. John Green, in reply to my questions on this subject, says that the stones used for making tomahawks were dug out of the quarries with a pole of hard wood. The stones were found in blocks, not much larger than the ordinary tomahawks, and shape was given to the blocks by striking off flakes with an old tomahawk. The cutting edge was formed and polished by grinding and rubbing on a piece of sandstone. Sometimes a stone was found in the bed of a creek or river, or on the sea-shore, of the desired form, and this was ground and sharpened, and used as a tomahawk; but such a stone was considered as very inferior to the tomahawk of greenstone shaped in the manner above described. Pebbles were never used by the men of the Yarra tribe if they could get the greenstone blocks. The greenstone was brought from a quarry near Kilmore, on a range called Mount Hope by the Europeans, and known as Wil-im-ee Moor-ring (Tomahawk-house) amongst the natives.

The flakes of basalt, &c., used for skinning animals, were struck off by blows given with an old tomahawk or some other suitable stone.

The wood of the silver wattle (Acacia dealbata) was used for making the handles of tomahawks. The native name of this wood is Ur-root. The piece of a bough chosen for a handle was pared on one side as far as the pith; it was then heated in the ashes of a fire, and bent with the hands. The gum used for fastening the handle to the stone was obtained from the silver wattle. The handle was tied with sinews (Berreep) from the tail of a kangaroo.

The Rev. Mr. Bulmer informs me that the natives of Gippsland never, as far as he can learn, got stones from a quarry for their tomahawks. They selected suitable stones amongst those lying on the sea-beach or in the bed of a stream. They shaped the cutting edge either with an old tomahawk or a piece of stone. They did this by striking it near the edge, so as to cause pieces in the form of flakes to fall off. As soon as the edge was thin enough, it was ground and polished on sandstone. The flakes called Kra-gan, used for jagged spears, skinning animals, &c., were made in the same way, namely, by striking the edge of a block of stone with an old tomahawk.

The old tomahawks from Gippsland in my collection seem to have been formed in the manner described by Mr. Bulmer.

He says that the natives often used pieces of reed, sharpened at the end, for skinning animals. Reeds are plentiful in many parts of Gippsland, and being easily obtained and readily fashioned, and quite as effective as the flakes of stone, it may be supposed that they were, as a rule, preferred. Broken spears, and reeds not suitable for spears, are always found at a camping place, and when quite dry and sharpened at the end, would be as good as a sharp flake for skinning the kangaroo, &c. It is not known whether reeds were used in other parts of Victoria for this purpose.

Uses of the Tomahawk.

The tomahawk—(Figs. 176-7-8-9, and 180)—called by the natives of the Yarra Merring, or Kul-bul-en-er-uk, or Galbiling n' garrook; by the men of Lake Condah Kar-rak-ing; and on the Lower Murray Pur-ut-three—is one of the most useful implements possessed by the Aborigines. A man never leaves his encampment without his hatchet. With its help he ascends trees almost as rapidly as the native bear can climb. He cuts a notch for his toes, and placing the hatchet between his teeth, so as to set free his arms, ascends one step, cuts another notch, and so on until the height he desires to reach is attained. The rapidity with which he climbs and his dexterity would surprise a stranger. With the stone axe he cuts open limbs of trees to get opossums out of the hollows; splits open trunks to take out honey or grubs or the eggs of insects; cuts off sheets of bark for his miam or for canoes; cuts down trees, and shapes the wood into shields or clubs or spears; cuts to pieces the larger animals of the chase, if necessary; and strikes off flakes of stone for inserting in the heads of spears and for skinning beasts and cleaning the skins. With an old tomahawk he will shape from a rough block of stone a new tomahawk. Its uses are so many and so various that one cannot enumerate them. It is sufficient to say that a native could scarcely maintain existence in Australia if deprived of this implement. It is not a weapon of offence; but in battle a man would not scruple to use it either for striking his enemy or in warding off blows. In secret expeditions, and when using the noose (Nerum) for strangling a victim, he would of course have his club or tomahawk ready for any emergency; and the tomahawk would be the easiest to carry, and the more certain to do execution.

|

| FIG. 199.—(Scale ¼.) |

Knives and Adzes.

The stone chisel or gouge (Fig. 199), of which there is more than one example in my collection, is formed of a fragment of quartzite, firmly set into the end of a rough handle of wood, and secured in its place by gum. The instrument is seventeen inches in length, and altogether is a good strong piece of work. Those I possess could be used effectively in hollowing a tarnuk or shaping a shield.

Mr. J. A. Panton says that this instrument is commonly used by the natives inhabiting the country north-east of the Grey Ranges (lat. 29° 30’ S., long. 141° 30’ E.).

I have not found it in Victoria; and I am indebted to Mr. Panton for the specimens I possess.

The stone knife (Fig. 200) is also from the north. Mr. Panton says it is used by the Aborigines of Booloo and Cooper's Creek. The stone is a hard, dense, rather granular quartzite. It has not been ground or polished—that is impracticable with such a stone—but it has been so skilfully fractured as to present a fine serrated cutting edge. The implement is altogether nearly eight inches in length. The stone is firmly fixed to the wooden handle by gum. With it one can easily cut wood, and in the hands of the natives it must have been a useful tool.

|

| FIG. 200.–(Scale ¼.). |

|

| FIG. 201.–(Scale ¼.) |

The stone knife (Fig. 201) is also formed of quartzite and by percussion. It would be almost impossible to grind or polish it. It is used by the natives of the Paroo. It is not provided with a wooden handle, but one end is encased in opossum skin (the fur outwards), so as to admit of its being grasped firmly and used easily.

This implement is in the possession of Capt. Rothwell, R.A., formerly Private Secretary to the late Lord Canterbury.

The people of New Zealand have axes and adzes not differing very much from those of the Australians; but in general the stone-head is nephrite. The head of one in my collection—a specimen which formerly belonged to Mr. A. Tighe—is exactly like the Australian stone axe. It has been formed by striking off flakes, and the cutting part has been ground. The wooden handle, however, is different. A notch has been cut in it, and the stone is inserted in the notch and tied with strong twine. It is a beautiful implement.

The stone-head is four inches in length, and rather more than two and a half inches in breadth, and it has a sharp edge. The wooden handle is nineteen inches in length.

Chips for Spears.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FIGS. 202, | 203, | 204, | 205, | 206, | 207. |

(Scale ⅓.)

Figs. 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, and 207 represent fragments of black basalt exactly similar, mineralogically, to the basalt which occurs at Malmsbury, and identified by Wye-wye-a-nine as chips that the Australians used in making jagged spears. The name of the chip amongst his people is Ped-th—(pronounced with a lisp).

These fragments were picked up in parts of the colony formerly frequented by the natives, but at great distances apart, and are undoubtedly pieces lost accidentally when the spears were in use, or dropped from bags when the Aborigines were travelling. They are to be found on the low schistose ranges which are almost bare of soil, in all parts; but where the deeper soils occur, they are, of course, concealed.

Chips for Cutting Scars, etc.

The chips Figs. 208 and 209 were shown to Wye-wye-a-nine with a great number of other fragments. When he had attentively examined them, he said that they had been used for cutting the flesh when the natives wished to raise scars. The name is the same as that given to the chips used in making jagged spears—Ped-th.

|

| ||

| FIGS. 208, | (Scale ⅓.) | 209. |

They are pieces of hard, dense basalt, and might be used, one would suppose, for inserting in spears; but Wye-wye-a-nine insisted that they were cutting instruments and nothing else.

In all cases where I had the opportunity of testing his statements by other evidence (and I had opportunities of doing this very often), I found him to be strictly accurate, and the discrimination displayed in selecting these as cutting instruments, from amongst a great number of other chips, which to the eye appear to be alike, is a proof that this native is possessed of faculties of a high order.

Chips for Skinning Opossums, etc.

This stone (Fig. 210) is used for skinning the opossum and other animals. It was at once identified by Wye-wye-a-nine. The name is simply Lah—a stone.

| FIG. 210.–(Scale ⅓.) |

Fragments of Tomahawks, etc.

|

| FIG. 211.–(Scale ⅓.) |

The stone shown in Fig. 211 is a piece of greenstone. A part of one side is highly polished, and the other is the rough surface of a fracture. This Wye-wye-a-nine recognised as a fragment of a tomahawk. It was found on the ranges; and its character was not known until Wye-wye-a-nine examined it.

The chips shown in Figs. 212-l6 were collected by Mr. Ulrich, and are thus described by Wye-wye-a-nine:—

Fig. 212 represents a fragment of a tomahawk (Pur-ut-three). It is a piece of hard, dense, black basalt.

Fig. 213 is also a piece of a tomahawk; it is, like Fig. 212, composed of black basalt, and certainly more resembles a chip which would be used for a jagged spear than anything else.

|

|

|

|

|

| FIGS. 212, | 213, | 214, | 215, | 216. |

| (Scale ⅓.) |

Fig. 214 is a chip for a chisel (Wot-thun).

Fig. 215 is a chip used in scraping spears. With this instrument the natives remove the bark and cut away excrescences. The name is Wallen-jah.

Fig. 216 is a chip for a jagged spear.

Chips for Skinning, Cutting Open, and Dressing Animals Killed in the Chase.

This chip (Fig. 217) was dug out of a Mirrn-yong heap by Mr. John Green, and he and others believed it had been used for skinning animals. It has a tolerably sharp cutting edge, and appears to be a fragment of chert. It has not been ground or polished, and the fracture is semi-conchoidal. I was quite sure it was an ancient chip that had been used in cutting open and skinning animals taken in the chase; but when Wye-wye-a-nine saw it he appeared to recognise it at once as a fragment struck off in making a tomahawk.

|

| FIG. 217.—(Scale full size.) |

Stones for Pounding and Grinding Seeds, etc.

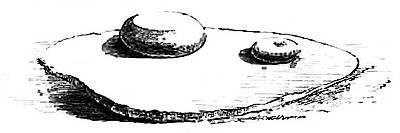

The grinding-stones (Fig. 218) used by the natives of the Darling are of the following description:—The slab, generally of sandstone, is about twenty-two inches in length, fourteen inches in breadth, and about one inch in thickness. The hand-stones (Wallong) are round, or of an oval form, and vary in size. One is four inches and a half in length, three inches and a half in breadth, and one inch and three-quarters in thickness; and another is six inches in length, four inches and a half in breadth, and three inches in thickness. The Wallong have hollows cut in them, so as to be more easily held by the hand.

Mr. Howitt says the stones here figured are like those usually seen at Cooper's Creek. In the flat stone there is a depression which leads out to the edge by a channel. In grinding grass or portulae seed a little water is sprinkled in by the left hand, and the seeds being ground with the stone in the right hand form a kind of porridge, which runs out of the channel into a wooden bowl (Peechee), or a piece of bark. It may then be baked in the ashes, or eaten as it is, by using the crooked forefinger as a spoon. The term used for grinding seeds is Bowar dakoneh.

Nardoo seeds are pounded by the above, placing a few in at a time with the left hand. The "tap-tap" of the process may be heard in the camp far into the night at times.

|

| FIG. 218. |

The slabs of sandstone used are, he was told, brought by the Cooper's Creek blacks from somewhere below the parallel of Mount Perll, out on the edge of the western plains (Flinders Range, South Australia).

In the Museum in Melbourne there are two stones—a slab and a stone—in shape like two cones placed base to base, which I am assured are used in some parts of the Darling for grinding nardoo. They are different altogether from the stones ordinarily employed for this purpose, and resemble those made by the Kaffirs. The round grinding-stone is very soft, and, owing to its shape, could be used in no other way than as the Kaffir women use it for reducing boiled corn to paste.

I have made careful enquiries, and I cannot learn that these stones are used anywhere in Australia.

Several sorts of stones are used for pounding roots and seeds. I have seen on the banks of creeks in Victoria hollows in isolated outcropping rocks which may have been used for the reception of seeds or roots. Certainly the stones I observed were hollowed by man, and probably have been employed for some such purpose.

Sharpening-stones.

|

| FIG. 219.—(Scale ¼.) |

Mr. E. J. Dunn collected a large number of stone implements in Victoria, and amongst them several sharpening-stones. These sharpening-stones are nearly all of the same shape.—(Fig. 219.) They are from four to six inches in length, two and a half to three inches and a half in breadth, and about one inch in thickness. They are dish-shaped, and the part used for polishing is smooth, and in some specimens much hollowed. In one case both sides of the stone have been used for sharpening. Some are of dense sandstone—nearly all quartz—and others of micaceous schists and sandstones of various degrees of hardness.

These stones were used for polishing the edges of tomahawks, and for finishing clubs, shields, &c. They are found occasionally on or a little beneath the surface of the ground all over the colony. When much worn, they are liable to break in the middle, and the half of a sharpening-stone of this kind is often seen.

Mr. Turner, of Mooroolbark, says that when polishing a tomahawk with a stone of this kind the native holds the stone between the toes of one foot, and slowly sharpens his axe, which he has in his right hand, by gently rubbing the edges in the hollow.

Wye-wye-a-nine says that amongst his people the men were accustomed to grind and polish their axes on any suitable stone that they could find, and that this was done day by day, as opportunity served. The same native saw an oval-shaped piece of rough gritty sandstone in my collection, which was sent to me by Mr. John Green as a specimen of the stone (Yourri-urrok) used for sharpening the heads of spears. He recognised it at once, and told me that the name of it in his tribe was Mirg-ma-rook, and that it was commonly employed for the purpose stated.

Another piece of stone—(Fig. 220)—a weather-worn fragment of micaceous sandstone, hard and gritty—was used for rasping the sapling and shaping it into the form of a spear. The name of this stone is Wallen-jah; and though bearing the same name as the fragment shown in Fig. 215, has not exactly the same use. The latter is used for scraping the sapling, the former for rasping and shaping it; the one is a cutting instrument, the other a sharpening-stone. This specimen was found by one of the Geological Surveyors in the basin of the River Loddon.

|

|

| FIG. 220.—(Scale ¼.) | FIG. 221.—(Scale ⅓.) |

This fragment (Fig. 221) was used for sharpening the points of the wooden spears. It also is named Wallen-jah in the Lower Murray district. It would appear that the natives had several stone implements all called Wallen-jah, which were employed in making spears at different stages of the operation.

The stone shown in Fig. 215—a chip of basalt with a cutting edge—was used for scraping off the bark and removing excrescences from the sapling; that shown in Fig. 220—a piece of rough sandstone of irregular form—as a rasp for giving a round form to it, and for smoothing it; and the fragment here figured (Fig. 221)—a chip of basalt—for polishing the points and in finishing it.

I have met with great difficulties in the endeavour to ascertain the uses of the several fragments which are in my collection. At one moment the statements of the natives seemed to be altogether irreconcilable with facts gathered from them respecting stone implements that to the eye of a European did not differ in character; but patience, and a careful attention to the explanations given by Aboriginals and others well acquainted with their tools and implements, have enabled me to place each in its proper position, and to discover how it was employed and for what purposes.

Stones used in Fishing.

This stone (Fig. 222) is said to be used by the natives of the River Murray when engaged in fishing with nets. When the nets are placed in the right position, the diver goes into the water at some point below the nets, and holding in each hand a stone of this kind, he makes a noise, by striking them together, which frightens the fish, and they rush up stream and are caught. Wye-wye-a-nine tells me that the stone has no name indicating the use to which it is put. It is simply Lah—a stone. The specimen in my collection is a hard, dense greenstone, with one face highly polished. The small indentation in the back for the reception of the point of the middle finger enables the diver to hold it securely in his hand. Wye-wye-a-nine grasped the stone as soon as he saw it, and showed me how it was used by the divers. Stones of a similar form are used for pounding roots, &c., and the stone here figured may have been used for such purposes when not required by the fishermen.

|

| FIG. 222.—(Scale ¼.) |

Stones used in making Baskets.

In making baskets the women commence by plaiting that part which is to form the centre of the bottom, and having completed this, they work around it, adding plait after plait until the full size of the bottom is attained. To steady and fix the work thus done, so that their hands may be free for weaving the sides of the basket, they use an implement named Weenamong. This most often is merely a flat smooth pebble picked out of the bed of a brook. It is usually about four inches in diameter, but for large baskets heavier stones are used. Whether large or small, the stone must be dense, and diorites and fine quartzites are accordingly employed.

I have often watched the women when engaged in this work. They use the stone adroitly, turning it from time to time in such a manner as to fix the bottom of the basket in the desired position while they weave a part of the side. To signify the beginning of the basket, they use the word Moom-newk, which is literally Moom, the bottom, and newk, the basket begun.

For Ruddle.

A piece of trap rock, named Boo-boorrn by the natives of the Murray, is put in the fire and kept there until it becomes red-hot. When taken out, the native scrapes from the surface a red powder, with which he makes a paint to color his shields and other weapons, to dye his rug, and, if necessary, to ornament his person. The native name of the stone is, on the Lower Murray, Noor-in-yoo-rook, and the name of the ruddle obtained from it is the same.

Pigments of various kinds were used by the natives, the character and composition of which are described in another place.

Bulk.

A stone—believed by the natives to possess extraordinary powers, and held in great estimation by the sorcerers—was presented to me by Mr. A. W. Howitt, who obtained it from an old man in Gippsland. It is egg-shaped, about four inches in length, and two and a half inches in breadth. It is thickly covered with oxyd of iron, and it is impossible to say, without breaking it, what its mineral composition is; but on clearing one small part of the thick coating of red oxyd, it presented an appearance like that of a trap rock. It must have had given to it the form which it now shows many, many years ago, and may indeed have been a treasure in the tribe to which the old man belonged before Australia was known to Europeans. The name of the stone is Bulk, and with it and other stones the priests work enchantment. It weighs twenty-seven and a half ounces.

Stones of this character are described by Grey. He says:—

"The natives of South-Western Australia likewise pay a respect, almost amounting to veneration, to shining stones or pieces of crystal, which they call Teyl. None but the sorcerers or priests are allowed to touch these, and no bribe can induce an unqualified native to lay his hand on them. The accordance of this word in sound and signification with the Baetyli mentioned in the following extract from Burder's Oriental Customs (vol. I., p. 16) is remarkable:—

"'And Jacob rose up early in the morning, and took the stone that he had put for his pillow, and set it up for a pillar, and poured oil upon the top of it, and he called the name of that place Be-thel.—Genesis XXVIII., 18. From this conduct of Jacob and this Hebrew appellation, the learned Bochart, with great ingenuity and reason, insists that the name and veneration of the sacred stones called Baetyli, so celebrated in all Pagan antiquity, were derived. These Baetyli were stones of a round form; they were supposed to be animated by means of magical incantations with a portion of the Deity, they were consulted on occasions of great and pressing emergency as a kind of divine oracle, and were suspended either round the neck or some other part of the body.'

"That this veneration for certain pieces of quartz or crystal is common over a very great portion of the continent is evident from the following extracts from Threlkeld's Vocabulary, p. 88:—

"'Mur-ra-mai, the name of a round ball, about the size of a cricket-ball, which the Aborigines carry in a small net suspended from their girdles of opossum yarn. The women are not allowed to see the internal part of the ball. It is used as a talisman against sickness, and it is sent from tribe to tribe for hundreds of miles on the sea-coast, and in the interior. One is now here from Moreton Bay, the interior of which a black showed me privately in my study, betraying considerable anxiety lest any female should see its contents. After unrolling many yards of woollen cord, made from the fur of the opossum, the contents proved to be a quartz-like substance of the size of a pigeon's egg. He allowed me to break it and retain a part. It is transparent, like white sugar-candy. They swallow the small crystalline particles which crumble off as a preventive of sickness. It scratches glass, and does not effervesce with acids. From another specimen, the stone appears to be agate of a milky hue, semi-pellucid, and strikes fire. The vein from which it appears broken off is one inch and a quarter thick. A third specimen contains a portion of cornelian, partially crystallized, a fragment of chalcedony, and a fragment of a crystal of white quartz.'

"And again, in Mitchell's Expeditions into Australia, vol. II., p. 338:—

"'In these girdles the men, and especially their coradjes or priests, frequently carry crystals of quartz or other shining stones, which they hold in high estimation, and very unwillingly show to any one, invariably taking care, when they do unfold them, that no woman shall see them.'"[9]

- ↑ "Indeed," as Professor Steenstrup well says, "these flakes are the result of such a small number of blows, they are so simple in appearance, that the art shown in their manufacture has generally been much underrated. Any one, however, who will try to make some for himself, while he will probably be very unsuccessful, will at least learn a valuable lesson in the appreciation of flint implements."—Pre-Historic Times (Lubbock), p. 193. "Many of the stone weapons and implements made by the Australian Aborigines are far superior in construction to the rude flint implements found in the European drift. The spear-heads in particular of some of the tribes are beautifully-finished articles, and conclusively prove that those who made them must have possessed an almost marvellous manual dexterity. In Captain King's account of his visit to Hanover Bay, he says:—'What chiefly attracted our attention was a small bundle of bark, tied up with more than usual care; and upon opening it we found it contained several spear-heads, most ingeniously and curiously made of stone; they were about six inches in length, and were terminated by a very sharp point. Both sides were serrated in a most surprising way. The serrature was evidently made by a sharp stroke with some instrument; but it was effected without leaving the least mark of the blow. The stone was covered with red pigment, and appeared to be a flinty slate. These spear-heads were ready for fixing; and the careful manner in which they were preserved plainly showed their value; for each was separated by slips of bark, and the sharp edges protected by a covering of fur. Their hatchets were also made of the same stone, the edges of which were so sharp that a few blows served to chop off the branches of a tree.'"—Australian Discovery and Colonization, by Samuel Bennett, p. 280.

- ↑ Mr. A. W. Howitt informs me that the natives of Cooper's Creek do not fasten wooden handles to the stone. They grasp the tomahawk with the fingers and thumb, holding the blunt end in the hollow of the hand, and use it in cutting exactly as the Tasmanians used the chips of chert which served them as hatchets.

- ↑ In the Life and Adventures of William Buckley the tomahawks used by the natives of Victoria and the mode in which the stone was obtained are thus described:—"The heads of these instruments are made from a hard black stone, split into a convenient thickness, without much regard to shape. This they rub with a very rough granite stone until it is brought to a very fine, thin edge, and so hard and sharp as to enable them to fell a very large tree with it. There is only one place that I ever heard of in that country where this hard and splitting stone is to be had. The natives call it Kar-heen, and say that it is at a distance of three hundred miles from the coast inland. The journey to fetch them is therefore one of great danger and difficulty—the tribes who inhabit the immediate localities being very savage and hostile to all others. … They vary in weight from four to fourteen pounds; the handles being thick pieces of wood split and then doubled up, the stone being in the bend and fixed with gum, very carefully prepared for the purpose, so as to make it perfectly secure when bound round with sinews."