The Achehnese/Volume 1/Chapter 1

CHAPTER I.

DISTRIBUTION OF THE PEOPLE, FORMS OF GOVERNMENT

AND ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE.

§ 1. Introduction.

Boundaries of Great-Acheh.The limits of the kingdom of Acheh[1] in Sumatra are placed by the Achehnese themselves at Teumiëng (Tamiang) on the East Coast, but far more to the South on the Western Coast, viz. at Baros or whatever other point they regard as marking the boundary between the territory of the princes of Menangkabau and that of the Sultans of Acheh. Far more restricted, however, is the territory they describe as "Acheh" proper, or as we are wont to term it, "Great Acheh".

This kernel of the kingdom, which has supplied the outlying districts with a considerable portion of their inhabitants, and has constantly striven to exercise more or less dominion over them, is according to the Achehnese idea bounded by a line extending from Kluang on the West, to Kruëng Raya on the North Coast, and passing through Reuëngreuëng, Pancha and Janthòë[2].

The form of this, the true Acheh, the Achehnese delight to compare to that of a winnowing-basket (jeuʿèë), as may be seen in the

JEUʿÉË (WINNOWING BASKET). THE ACHEHNESE COMPARE THE FORM OF TRUE ACHEH TO THIS.

illustration[3]. The debouchement of the Acheh river (kuala Acheh) suggests to their fancy the somewhat sharply pointed mouth of the winnower, whence all unclean particles adhering to the husked rice are shaken out.

Proceeding down stream, we have the territory of the XXV Mukims[4] on the left and that of the XXVI Mukims on the right, the intervening space up to the broad belt of outlying country being occupied by the XXII Mukims. A comparison with the three angles of a triangle has still more deeply engrafted itself into the language; these three confederations or congeries of mukims are called the thèë sagòë (Mal. tiga sagi) i. e. the three angles of Acheh, and the three ulèëbalangs or chieftains who stand or are supposed to stand at the head of these three districts, are called panglima sagòë, or heads of sagi or angles.

History of Acheh.The history of this “triangular kingdom” and of the coast-states and islands which constituted its dependencies remains yet to be written. European sources of information, such as accounts of travels and extracts from old archives, can only furnish us with very fragmentary materials; yet it is to these that we should have to look for the basis of such a work. Malayan chronicles and the native oral tradition, though furnishing us with much of interest as regards the methods of thought of the writers and their coëvals, cannot be relied on as the groundwork of history. They are but collections of fabulous genealogies, legends and tales dressed up to suit the author’s fancy, which must be subjected to a careful process of filtration before they can be brought into unison with more solid materials.

Our present purpose is to describe how the Achehnese live and how they are governed, what they think and what they believe. As the present has ever its roots in the past, a retrospective glance over the earlier history of Acheh might be of great service to us in this enquiry were it not that, for the reasons just stated, this history is to a great extent wrapped in obscurity. As regards history, then, we limit ourselves to what our discussion of existing institutions brings to light en passant and for further information refer our readers to Prof. Veth's Atchin pp. 60 et seq., where the principal historical traditions are set forth in detail.

In the present chapter we propose to give a review of the distribution of population, the government and administration of justice as they existed before the Achehnese war introduced an element of confusion.

As a matter of fact, however, the disorder thus created has left the main features untouched; and anyone who has some knowledge of the public institutions of other kindred nations will if he follow our description be brought to the conclusion that these institutions in Acheh are in a large measure genuinely indigenous and of very great antiquity.

Significance of the manuscript documents respecting the institutions of the country.Our purpose differs from that aimed at by Mr. K. F. H. Van Langen in his essay on the system of government in Acheh under the Sultanate[5]. He takes as his chief sources of information one or two manuscript documents, known in Acheh under the name of sarakata. They contain decrees having the force of law and are ascribed to Sultans Meukuta Alam or Iskandar Muda (1607–1636) and to Shamsulalam, who reigned for a period of one month only (1726–27) according to the Achehnese chronicles. The writer has illustrated and completed the contents of these documents from the oral tradition of the Achehnese.

To assign their true value to these documents we must allow ourselves a slight digression.

It is abundantly clear from all the sources of Achehnese history, be they native or European, that there has never been an opportunity in Acheh for a regulated and normal development of forms of government or administration of justice. In vain do we seek in any period of her history for order and repose. It is not to be found even during the reigns of those princes who shed the greatest prosperity and lustre over the land, such as Alaudin al-Qahar[6], known also as Sidi Mukamil or Mukamal (1540–67), Eseukanda (Iskandar) Muda or Meukuta Alam (1607–36)[7], not to mention their successors.

Examined closely, this show of royal grandeur is found to consist in some enlargements of territory, increase of authority over the ports (which are the seats of civilization and wealth in all Malayan countries) and consequent increase of revenue, which gave rise to greater splendour at court, but no serious effort towards the establishment of solid institutions such as survive the overthrow of dynasties.

The only attempts at centralization of authority, or reformation whether social, political or religious, are precisely these very edicts which we have just referred to. Of the contents of these by no means ample political fragments it may be said that hardly a single one of the innovations they comprise has passed from document into actuality, but simply that the state of things they reveal as already in being has continued its existence.

It is not difficult to distinguish in these edicts the old and already established conditions from the new ones which they purport to introduce.

The principal features of this old status were the great independence of the numerous chiefs and the all-prevailing influence of traditional custom.

The new elements may be classified as follows:

1°. Attempts at an extension of the authority of the Sultan by allotting to him, the king of the port, a certain control over the succession of the other chieftains of the land—a matter which for the rest is treated in these edicts as inviolable—over the disputes of these chiefs with one another, or those between the subjects of different chiefs, and over the interests of strangers. In a word, some very moderate efforts at centralization of authority, having it for their object to make the Sultan primus inter pares; the establishment of a kind of indication of fealty, meant to serve as an open and visible reminder of the existence of such a relation between Sultan and chiefs.

2°. Certain rules intended to bring about a stricter observance of Muhammedan law.

3°. Regulations dealing with trade (then confined to the capital) the shares of certain officials established in the capital in the profits drawn from this trade by the king of the port, the court ceremonial, the celebration of great religious festivals etc.

During my residence in Acheh I obtained copies of a number of other sarakatas not included among those published by Van Langen. They were as a rule lengthy documents and most of them bore dates. The following are examples: one of Meukuta Alam or Eseukanda (Is-Muda, dated 1607, revived by the princess Sapiatōdin in 1645, intended kandar) to regulate the court ceremonial and solemnities at festivals (very rich in details); two of Meukuta Alam = Eseukanda (Iskandar) Muda, dated respectively 1635 and 1640 (sic); one of Jamalul-Alam (in Achehnese Jewumaloj) dated 1689, revived by Alaédin Juhan, the second prince of the latest dynasty, in 1752; one of Alaédin Mahmut dated 1766; and certain undated edicts of Sapiatōdin, Amat Shah Juhan (the first prince of the latest dynasty) and Badrudin Asém (Hashim), all dealing with commercial and port regulations as affecting different nationalities and different kinds of merchandise, and the collection and distribution of taxes. In these we even find detailed customs-tariffs[8].

These documents are identical in spirit and intention with those published by Van Langen; but they contain much more information as regards the ceremonial of court and festival and the collection and disposal of taxes on imports, and are occasionally at variance with the latter as regards details.

What has been the practical development of the three new elements introduced by these edicts?

The rules noticed under heading 3° above are those which have had most significance in actual practice. Of these we may say that they exercised, during the reign of their promulgator at least, some degree of authority over life and trade in the seaport town. To assert more than this is to go outside the bounds of probability and to come into conflict with unimpeachable data. Perpetual dynastic struggles leading to the death or downfall of the rulers, the unstable character of these rulers themselves, the endeavours of chiefs and officials even in the capital to promote their own authority and profit, the want of a proper machinery of government based on other principles than "might is right", all this and much more serves to establish the fact that in the history of Acheh no period can be pointed out in which even these regulations affecting the capital have passed current as the living law of the land.

The religious elements mentioned under heading 2° were certainly not introduced into the edicts through the zeal of the princes of Acheh, any more than the proclamations of appointments of Achehnese chiefs (as drawn at the Court down to the present time) can be said to owe their almost entirely religious contents to the piety of the princes or of the appointed chiefs themselves. A Moslim prince augments his prestige vastly by such concessions to the law of his creed, albeit a serious and strict application of the latter would greatly curtail his power and impede his actions. Besides (and this is a most important factor) the supporters of the sacred law have in such countries no inconsiderable influence over the people, so that it might be dangerous for the princes and chiefs to disregard their wishes and requirements[9]. This is fully understood by these potentates, most of whom, while they follow their own devices in the actual administration of government, are wont outwardly to show all possible honour to the upholders of religion, to declare verbally that they set the highest value on their wisdom, and now and then, merely as a matter of form, to grant them access to their councils.

Such has been the system of the Achehnese sovereigns. Ulamas and other more or less sacred persons enjoyed considerable distinction in their country and at their court. They used even to "give orders" for the compiling of manuals of theology and law, which in plain language meant that they made a money payment to the writer of such a book. They would even allow themselves occasionally to be persuaded by some person of unusual influence to undertake a persecution of heretics, which however generally proved quite abortive. In their legislative edicts, which are almost all devoted to questions of trade and court affairs, they have in a fashion of their own rendered unto God the things that are God's, and so far as these ordinances confine themselves to what we should call a purely religious sphere, we have no reason to doubt the good intentions of the law-givers. Though their fleshly weakness was apparent from their irreligious life, their spirit was willing enough to remember the life hereafter, when the question came up of the building of mosques, the apportioning of money for religious purposes, the dispensing of admonitions or even the threatening of punishment for neglect of religious duties. But of any effort to introduce a system of government and administration of justice in harmony with the Mohammedan law we can gather nothing from the language of the edicts. They render in a purely formal manner due homage to the institutions ordained of Allah, which are everywhere as sincerely received in theory as they are ill-observed in practice[10].

Still more exclusively formal are the admonitions dispensed to the chiefs in the royal deeds of appointment. One might almost assert that the raja of Acheh who sanctioned the form of these documents must have charged his ulamas with the acceptable task of drawing them up.

Thus Acheh had sovereigns who were lauded to the skies, especially after their death, by ulamas and other pious persons who basked in the sun of their good deeds and who actually saw some of their own devout wishes realized; yet religion had little influence on the formation of her political system, less even than might be assumed from the dead letter of isolated edicts of the port-kings.

It requires no proof to show that not one of these cautious efforts at centralization of authority mentioned above under head 1°, seriously enough meant though they were, was eventually crowned with success. The most powerful sultans dared not go further than to claim a certain right of interference, constituting themselves as it were a supreme court of arbitration. It may at once be concluded how far the rest of the petty rulers of both sexes progressed in this direction, weak and indolent as they were in disposition and fully taken up with anxiety to maintain their authority in their own immediate circle. So far from lording it over the Achehnese chiefs, they were compelled to seek their favour so as not to lose their own position as kings of the ports.

Besides this it must be considered that though the Achehnese sovereigns might have gained some increase of prestige from the establishment of their authority in the interior, still this was not of sufficient importance to induce them to make great sacrifices to win it. It is the ports, let it be repeated, that constitute the wealth and strength of states such as these.

Where a port-king possesses the means and the energy to extend what he has already got, he prefers to stretch his covetous hand towards other ports, and tries to divert their trade to himself or to render them tributary. This he finds much better than meddling with the districts, desert and inhospitable both in a spiritual and material sense, which hide the sources of his kualas or river-mouths.

Nor do these rulers endeavour to ensure the permanence of their dominion in other ports which they have subdued by taking as its basis the introduction of an orderly form of government. The conquerors are content with the recognition of their supremacy and the payment of dues.

Thus it is very easy to show how the rajas of Acheh during the short-lived period of prosperity of their kingdom, kept the trading ports within a wide compass in subjugation with their fleets, but never got any further in the control of the interior than the issue of a few edicts on paper.

We must not then allow ourselves to be misled by these edicts, valuable as they are as sources of information as to the history of the kings of Acheh. The danger of such error presents itself in two ways.

In the first place, the Achehnese himself, when questioned as to the institutions of his country, will refer with some pride to these documents, notwithstanding that most Achehnese have never seen copies of them and are almost entirely unacquainted with their contents.

The ordinary Achehnese does this, because all that recalls to him the greatness of his country is closely connected with the names of those very princes who are generally regarded as the authors of the sarakatas. He firmly believes that all that he reveres as the sacred institutions of his country (albeit not mentioned in a single one of the edicts) is adat[11] Meukuta Alam or at any rate adat pòten meureuhōm, "adat of defunct royalties", and he is convinced that information respecting them is of a certainty contained in some one or other of the sarakatas.

The Achehnese chiefs have a secondary aim when they refer with a certain emphasis to these edicts as the laws of Acheh. All that is contained therein respecting court ceremonial, festivals, religion etc., they regard with complete indifference; but every one of them is skilful in making quotations from the adats of the old sovereigns handed down in writing or by word of mouth, which may go to show that his power, his territory, or his privileges should in reality be much greater than what he enjoys at the present time.

The European who comes into contact only superficially with the native community, is too apt to think that the adat among them is an almost unchangeable factor of their lives, surrounded on every side with religious veneration. Yet it does not require much philosophic or historical knowledge to be convinced that such invariable elements subsist just as little in the native world as in our own, although among them the conscious reverence for all that is regarded as old and traditional is stronger than in our own modern societies. In contrast to the changeableness of the individual, the adat presents itself as something abiding and incontrovertible, with which that individual may not meddle; yet the adat changes like all other worldly things with every successive generation,—nay, it never remains stationary for a moment. Even natives, whose intelligence is above the ordinary, know this well and use it to further their own purposes.

The slowly but surely changing institutions of their society are thus revered as fixed and unchangeable by its individual units. But it is precisely in this connection that opportunity is given for continual disputes as to the contents of the adat[12]. What is, in fact, the real and genuine adat, that which according to unimpeachable witnesses was formerly so esteemed, or that which the majority follow in practice at the present day, or that which many, by an interpretation opposed to that of the majority, hold to be lawful and permitted?

Most questions of importance give rise to this three-fold query, and the answer is, as may be readily supposed, prompted by the personal interest of him who frames it.

Our object being to arrive at some knowledge of the institutions of the country, it is impossible for us to accept the reference of the Achehnese to the edicts of the kings of olden times, which are absolute mysteries to most of them, whilst others construe them to suit themselves.

Even apart from the danger of accepting such reference as gospel, the European is exposed to a further risk, namely of misunderstanding the true signification of such edicts. Accustomed to the idea that all law should be suitably drawn in writing, he is apt to be overjoyed at coming on the track of a collection of written ordinances, especially in a place characterized by such hopeless confusion as the Achehnese states. So when he perceives that there is now little or no actual observance of these laws, he rushes to the conclusion that at an earlier period order and unity preceded the present misrule. The very contrary of this can be proved to be the case as far as Acheh is concerned. As a general rule we do not sufficiently reflect that in countries of the standard of civilization reached by the Malayan races, the most important laws are those which are not set down in writing, but find their expression, sometimes in proverbs and familiar sayings, but always and above all in the actual occurrences of daily life which appeal to the comprehension of all.

Speaking of Acheh only, there will be found described hereafter laws which control the relation of chief to subject, of man to wife and children, laws which everyone in Acheh observes and every village headman has at his fingers' ends; and yet of all these living laws no single written document testifies[13], though every single sentence of an Achehnese judge bears witness to their existence.

Such has been the case all over the East Indian Archipelago. Whoever would introduce by force an alteration in existing legal institutions found it necessary to reduce his innovation to writing, but those who were content to leave things as they were, seldom resorted to codification of the customary law. Whether changes such as these are abiding or disappear after a brief show of life, the writing remains as their witness; it is the life of the people alone that testifies of institutions which have withstood the attack of external change and modify themselves intrinsically by almost imperceptible degrees.

One might even assert that where codification of the customary law has been purposely resorted to (as in the undang-undang[14] of certain Malay states) this embodiment in writing is a token that the institutions in question are beginning to fall into decay[15]. Collections of documents of this sort offer to the conscientious enquirer a string of conundrums impossible of solution, unless he be thoroughly conversant with the actual daily life of native society, of the traditions of which such legal maxims form but a small part.

What we have said above perhaps renders it superfluous to add that we should be wandering altogether off the right track in seeking for the laws and institutions of countries such as Acheh in lawbooks of foreign (e. g. Arabic) origin. Such works are it is true, translated, compiled and studied in the country, but their contents have only a limited influence on the life of its people[16]. It is owing to a misconception of this very obvious truth that the entirely superficial enquiry of Mr. der Kinderen (or his secretary Mr. L. W. C. Van den Berg) has proved abortive, as may be seen from his "explanatory memorandum" just referred to. To any one who has made himself acquainted with the political and social life of the Achehnese, his remarks on pp. 17–18 of his memorandum will sound as audacious as they are untrue: "Nor indeed is there any trace of ancient popular customs in conflict with Islam, at least in the sense that would indicate a customary law having its existence in the consciousness of the people, as is the case for example with the characteristic institutions regarding the law of person and inheritance which we meet with among the Malays on the west coast of Sumatra. The native chiefs when questioned as to such popular customs, either gave evasive answers, or quoted as such certain rules for the ceremonial in the Kraton, the distinctive appellations of various chiefs etc., all of course institutions of a wholly different sort from what was intended by the enquirer. Apparently they misunderstood the drift of the question and confused the material with the formal and administrative law. Only one of them, who, it may be remarked was no Achehnese by birth, but of Afghan descent, absolutely denied the existence of any legal institutions conflicting with the Mohammedan law.

| · | · | · | · | · |

No one could have recorded in a more naive manner the want of intelligence which he brought to bear on his enquiry.

The Achehnese in general and their chiefs in particular will have themselves Mohammedans and nothing else. Within a few years previous to the visit of Mr. der Kinderen to Acheh, they had for the first time come under the control of a non-Mohammedan power, and regarded their new masters with distrust, all the more as a rumour had gone abroad that the "Gōmpeuni"[18] was everywhere endeavouring to introduce its Christian laws and to draw the Mohammedans away from their own religion. No wonder then that the chiefs "gave an evasive answer", or imparted little pertinent information in reply to the foolish query of Mr. der Kinderen and his friends (who had never come into contact with the people) as to whether there were ancient customs prevalent in Acheh conflicting with the law of Islam. Supposing it to be true that they "did not understand the meaning of the question", the blame for this rests on him who asked it. It is undoubtedly the easiest way to conduct an enquiry to address a sort of catechism to some individuals, and then to accept as of solid worth any follies they may choose to retail to you in reply, but to do so is to trifle with a serious subject.

The chiefs were naturally afraid that an affirmative answer might give rise to all kinds of new enactments "in conflict with the law of Islam". Besides, they would be very slow to admit that any of their institutions was in conflict with Islam, and indeed are as a rule quite ignorant as to whether such is the case or not, being neither jurists nor theologians. They are all trained up in the doctrine that adat (custom law) and hukōm (religious law) should take their places side by side in a good Mohammedan country—not in the sense inculcated by the Moslim law-books[19], that they should fall back on the adat whenever the hukōm is silent or directs them to do so—, but in such a way that a very great portion of their lives is governed by adat and only a small part by hukōm. They are well aware that the ulamas[20] often complain of the excessive influence of the adat and of its conflict with the kitabs or sacred books, but they do not forget that they have themselves cause to complain of the ambition of these ulamas. They account for this conflict by the natural passion all men feel for extending their authority, a passion they believe would be reduced to a minimum or altogether extinguished if all men tried to be just. They see herein no conflict between Mohammedan and non-Mohammedan elements, but between Moslim rulers who "maintain the adat" according to the will of God, and Moslim pandits who "expound the hukōm", both of which parties, however, sometimes overstep their proper limits.

They have no touchstone to distinguish exactly between what is in accordance with Islam and what conflicts therewith. All their institutions they regard as those of a Mohammedan people and thus also Mohammedan, and these they wish to guard against the encroachments of the kāfir[21].

That Mr. Der Kinderen and his friends found "no trace of popular customs in conflict with Islam" or of "a customary law having its existence in the consciousness of the people", is as natural as the disappointment of an angler who tries to catch salmon in a wash-tub. They exist all the same, these adats, they control the political and social life of Acheh, but—pace all dogmatic jurists and champions of facile methods—they are nowhere to be found set down in black and white. We arrive at them only after painstaking and scientific research and not through the putting of questions which the questioned "apparently do not understand".

To be explicit and avoid all misunderstanding, we should add that Mr. Der Kinderen in a later part of his memorandum (pp. 10 et seq.) states the case as though this faithful observance of Mohammedan law had existed originally in Acheh at an earlier epoch, while the few adats conflicting therewith had crept in later on during the period of anarchy and corruption. "The Achehnese chiefs", he goes on to say, "with whom we conferred, unanimously desired the maintenance of Islam and nothing more".

We shall see later on, when we come to examine the question in detail, that this comparison between an orderly past resting on the basis of the Mohammedan law and a disorderly present, is entirely chimerical and rests on false or inexactly stated data. These premisses for instance are false, that in earlier times many works on Mohammedan law were composed by Achehnese, that general ignorance now prevails as to the contents of these or that the wholly unlettered Teuku Malikōn Adé was supreme judge of the kingdom of Acheh. The ignorance of the chiefs in regard to Mohammedan law is wrongly explained; it is in fact an ignorance which they share with the rulers of most Mohammedan countries.

Nature of the popular and political institutions of Acheh.We postpone for the present the closer refutation of these extravagances. Let us now fix our attention on the fact that the non-Mohammedan institutions of the Achehnese, which we are now about to describe, and which taken together form a well-rounded whole, exhibit themselves to the scientific observer after comparison with those of other kindred peoples, as really indigenous and wholly suitable to the state of civilization in which the Achehnese have moved as long as we have known them. In vain shall we seek for any period in the history of Acheh in which we should be justified in surmising the existence of a different state of things. All that we know further of that history makes it patent that neither the efforts of the ulamas to extend the influence of the Mohammedan law, nor the edicts of certain princes whose authority over the interior was very limited and of short duration, were able to exercise more than a partial or passing influence on the genuinely national and really living unwritten laws.

The golden age of Acheh in which "the Mohammedan law prevailed" (see p. 16 of Mr. Der Kinderen's memorandum), or in which the Adat Meukuta Alam may be regarded as the fundamental law of the kingdom, belongs to the realms of legend. If we wish to become acquainted with the institutions of Acheh we must, in default of any written sources of information, devote ourselves to the study of their political and judicial systems and family life as they subsist at the present time. In these we can easily discover some traces of the centralizing activity of one or two powerful princes, an important measure of influence exercised by Islam and a still more important basis of indigenous adat law.

It must be borne in mind that even the most primitive societies and the laws that govern them never remain stationary. Keeping this in view it becomes easy to trace here and there efforts after change, and elsewhere again institutions which have already passed into disuse and owe their continued existence in a rudimentary form simply to the force of human conservatism. This makes us careful in forming judgments as to the antiquity of any given institution taken by itself, as we are not fully acquainted with the factors which may in earlier times have exercised a modifying influence. Still we are able with one glance over the whole existing customary law of Acheh to assert without fear of error that the institutions of that country do not date from yesterday but that, (disregarding alterations in details), they have in all main essentials existed for centuries past.

§ 2. Elements of Population.

In Acheh we have to deal, not with an originally powerful monarchy which gradually split up into small parcels, but with a number of little states barely held together by the community of origin of their citizens and the nominal supremacy of the port-king. We must obviously therefore, in describing the political fabric of Acheh, work upwards from below; and as in that country all authority of the higher classes over the lower is exceedingly limited, we must first devote our attention to the people who inhabit Great Acheh[22].

Origin of the Achehnese.We have at our disposal no single historical datum from which we can deduce any likely conclusion as to the origin of the Achehnese. We can only allege on various grounds that it must have been of a very mixed description.

A comparison of the Achehnese language (which exhibits noteworthy points of difference from the kindred tongues of neighbouring peoples), with those of Cham and Bahnar[23] has at the very outset given important results, but we must for the present refrain from deciding what may be deduced therefrom as regards the kinship or historical connection between the peoples.

Of the information supplied by the Achehnese themselves as to their descent, we furnish here only such particulars as may be classed as popular tradition. Outside the limits of this tradition every Achehnese chief and ulama who takes any interest in the question has his own conjectures, partly in conflict with the traditions and partly grafted on to them.

Achehnese theories.To the sphere of these conjectures belongs almost all that can be gathered from the Achehnese as to the Hindu element in their origin. It is past all doubt that Hinduism exercised for a considerable time a direct or indirect influence on the language and civilization of Acheh, though there is but little trace of such influence remaining in her present popular traditions and institutions. Even in Mohammedan times there are numerous indications of contact with the inhabitants of India; it is indeed more than probable that Acheh, like other countries of the Indian Archipelago, was mohammedanized from Hindostan. Not only Mohammedan Klings and people from Madras and Malabar, but also heathen Klings, Chetties[24] and other Hindus, have carried on trade in Acheh down to the present time, and there has been from first to last no serious opposition to the permanent establishment in the country of such kafirs, harmless as they were from a political point of view. For all that, the question as to what Hindus or people with Hindu civilization[25] they were, who exercised a special influence in Acheh, or what the period was when this influence made itself felt, remains enveloped in doubt. Still less is it certain in what degree Hindu blood flows in the veins of the Achehnese.

How these conjectures sometimes originate and gain credit in Acheh may be illustrated by an experience of my own in that country. The well-known Teungku Kutakarang, an ulama and leader in war [died November 1895] upholds, among other still more extraordinary notions, the view that the Achehnese are composed of elements derived from three peoples, the Arabs, the Persians and the Turks. Both in conversation and in his fanatical pamphlets against the "Gōmpeuni" he constantly refers to this theory.

Though he has absolutely no grounds for this absurd idea, those who look up to him as a great scholar think that he must have a good foundation for it, and accept his ethnological theories without hesitation. While I was engaged in collecting Achehnese writings and was making special efforts to secure copies of one or two epic poems based on historic facts, an Achehnese chief suggested to me that I should not find what I wanted in these. He declared himself ready to write me out a short abstract of the history of Acheh containing a clear account of the origin of the Achehnese from Arab, Persian and Turkish elements! "Of this", said he, "you will find no mention in the poems you seek for".

The only fact that popular wisdom can point to as regards the Hindus, is that the inhabitants of the highlands of the interior are manifestly of Hindu origin, since they wear their hair long and twist it into a top-knot (sanggōy) on the back of the head in the Hindu fashion.

ManteThere are other stories in circulation about the Mante or Mantras[26], but these are equally undependable. They remind me of what I once heard said of the tailed Dyaks reputed to exist in Borneo; the existence of these people, my informant remarked, appeared quite probable from what one heard of them all over Borneo, but they always seem to live one day further inland from the point reached by the traveller.

These Mantes are supposed to go naked and to have the whole of their bodies thickly covered with hair, and are believed to inhabit the mountains of the XXII Mukims; but all our informants know them only by hearsay. One here and there will tell you that in his grandfather's time a pair of Mantes, man and wife, were brought captive to the Sultan of Acheh. These wild denizens of the woods, however, in spite of all efforts, refused either to speak or eat and finally starved themselves to death.

In Achehnese writings and also in the speech of everyday life, rough clownish and awkward people are compared with the Mante. The word is also used in the lowlands as a nickname for the less civilized highlanders, and is applied in the same sense to the people of mixed descent on the West Coast.

Malay and Kling elements.Another contemptuous appellation of the West Coast people is aneuʾ jamèë (descendants of strangers or guests), or aneuʾ Rawa, (people from the province of Rawa), to which latter nickname the epithet "tailed" (meuʾiku) is also added[27]. That these tailed or tail-less strangers contributed their quota to the composition of the Achehnese race is as little doubted as that the multitude of Klings (Kléug, ureuëng dagang[28]) in Great Acheh and on the East Coast have brought more half-caste progeny into the world than now commands recognition as such. There have been within the memory of man a large number of Klings in the highlands of Great Acheh (XXII Mukims) living entirely as Achehnese and engaged in agriculture. There were even gampōngs, such as Lam Aliëng, the entire population of which consisted of such hybrid Klings. In Great-Acheh the word ureuëngdagang = stranger is employed without any further addition to indicate a Kling.

The shares contributed by all these foreign elements and also the Arabs, Egyptians and Javanese are rightly regarded as having a merely incidental influence on the Achehnese race. In the capital and the coast towns of tributary states, they form an item of greater importance, for it is precisely the most influential families that are of foreign origin. All the holy men and most of the noted scholars of the law in Acheh were foreigners. So too with many great traders, shahbandars, writers and the trusted agents of princes and chiefs; nay, the very line of kings which has ruled with some interruptions since 1723 is according to tradition of Bugis origin.

Nias slaves.Slaves are a factor of importance in the development of the Achehnese race. Most of these slaves come from Nias (Niëh), whence they were kidnapped in hundreds up to a few years ago, and are still surreptitiously purchased in smaller numbers.

It is worthy of note that the story current in Acheh as to the origin of the Niasese resembles that which prevails among the Javanese as to the Kalangs[29]. The same story in a modified form is popular in Bantén, but in the absence of Kalangs it is there applied to the Dutch.

A princess who suffered from a horrible skin-disease was for this cause banished to Niëh. (Achehnese pronunciation of Nias), with only a dog to bear her company. On that island she found many peundang plants, and gradually became acquainted with the curative properties of the peundang root[30].

It is not clearly stated what the circumstances were which induced her to marry her dog[31]; but we are informed that from this wedlock a son was born. When he grew up he wished to marry; but Nias was uninhabited. His mother gave him a ring to guide him in his search for a bride; the first woman he met whom the ring fitted was to be his destined wife.

He wandered throughout the whole island without meeting a single woman; finally he found his mother again and the ring fitted her! So they wedded and from this incestuous union is descended the whole population of Nias.

In this legend typifying the vileness of the origin of the Niasese there is wanting one feature which characterizes the Javanese myth of the Kalangs. Both have in common the dog and the incestuous marriage, but the Kalangs have in addition to this as their ancestress the most unclean of all animals, the swine. The princess who lived in the wilderness is in the Kalang legend the offspring of a wild sow, which became her mother in a miraculous manner[32].

Thus although no swine appears in the genealogical legend as forming part of the family tree of the Niasese, the story goes that they are the descendants of dogs and swine, and there is a doggerel verse in ridicule of the Niasese or persons of mixed Nias descent which runs as follows;—

"Niëh kumudèë—uròë bèë buy, malam bèë asèë i. e. "Niasese, that eats běngkudu fruits[33], smells like a pig in the daytime and like a dog at night".

In spite of all these sayings and stories (to which may be added the fact that kurab or ringworm is still very prevalent among the Niasese), the Achehnese set a high value on these people as slaves. They describe them as tractable, obedient, zealous and trustworthy. The women are more highly prized for their beauty than those of the dominant race, and many of the boys who as sadati (dancers) or otherwise are made to minister to the unnatural lusts of the Achehnese are of Niasese origin.

Later on when we come to describe the family life of the Achehnese, we shall see that he lays great stress on descent from the mother's side. Thus no Achehnese willingly becomes the father of children by his female slaves, although such a practice is freely admitted by Moslim law. It is for this reason that the intercourse of masters with their female slaves is very limited in comparison with other Mohammedan countries, and where it does take place, recourse is had to various methods to avert or nullify its natural consequences. All the same there is a certain proportion of children born of such concubinage.

There are, however, other channels through which Niasese blood has found its way into the veins of the Achehnese. For instance it not uncommonly occurs that a man who makes a long stay in a particular place, marries the slave of one of his friends or patrons. It even happens at times that an Achehnese makes such a marriage at or in the neighbourhood of his own home, setting at defiance the reproaches and hatred of his next of kin for the sake of the beauty of the woman he has chosen.

According to the Moslim law children born of such unions are the slaves of the owner of the mother, for when the question is one of slavery or freedom the children follow the mother as a matter of course. The Achehnese adat, on the other hand, treats them as free; but their origin is indicated by the name aneuʾ meuïh ("children of gold", i. e. of proprietorship), and thus not at once lost sight of. A generation or two later the name aneuʾ meuïh is dropped, and their descendants become Achehnese.

Children born of marriages between slaves (generally of the same master) are themselves slaves in Acheh; but many owners set their slaves free in later life. Such free Niasese do not except in rare cases intermarry with Achehnese women; their children, however, may take wives of mixed Achehnese and Niasese descent, and in the third generation they too are Achehnese, though with a slight Nias taint.

Those who can only keep one or two male slaves generally let these remain unmarried their whole life long, the supposition being that they will find frequent opportunities of intercourse with their own countrywomen.

The Achehnese are on their own confession indolent and little fitted for regular work. This is the reason they give for the occasional importation of rice into a country possessing vast tracts of uncultivated ground[34]. There is no doubt that in days gone by they used to get their work done for them by the Niasese. Not only did they employ them for ordinary tillage and for pepper cultivation, but also as soldiers in the endless little wars that divided the country against itself. Thus it is said that during the civil war of 1854–58 of between Raja Sulòyman (Suléman) and his guardian Raja Ibrahim[35], the supporters of the latter in particular usually employed Niasese to carry out all operations against the enemy.

Bataks.In comparison with the Niasese, the number of slaves of other races in Acheh is inconsiderable. Male Bataks[36] (but very seldom females) are occasionally kept as slaves, but the character given them is as bad as that of the Niasese is good. The Bataks are spoken of as unwilling, lazy and revengeful. Every Achehnese can furnish plentiful examples of this either from his own experience or what he has heard from others—how one Batak has treacherously murdered his master through anger at a trifling chastisement, and another after having been treated with the utmost kindness has made himself scarce after putting his masters children to death, and so on[37].

Other elements.Some few persons of position have permitted themselves the luxury of importing Chinese female slaves from the Straits Settlements as concubines[38]. Still more common is it to see slaves brought home from Mekka by those who have performed the Hajj. These Africans are known by the Achehnese under the generic name of Abeusi[39] (Abyssinians) irrespectively of what may be the land of their birth. Concubinage with female slaves of such origin is extremely rare; they are allowed to marry among themselves or with Niasese slaves. It is considered a mark of distinction to have such Abeusis as household servants[40].

Achehnese slave-law.As we noticed above, the Achehnese slave-law is not wanting in departures from the Mohammedan code. To these may be added the fact that it is everywhere thought natural and permissible for all who acquire slaves at once to violate their female captives. Even in Arabia the prescribed period of abstention in regard to purchased female slaves is seldom or never observed[41], but in Acheh no disgrace whatever attaches to its violation, and most of the transgressors are absolutely ignorant that they are sinning against that very law which they look upon as sanctioning kidnapping.

In the highlands far fewer slaves are kept than in the lowlands, as in the former there is less to be found of all that tends to make life easy or pleasant.

What has been said suffices to indicate the races which have in historic times contributed to ennoble or degrade the people of Acheh. Apart from this we must accept that people as an established unity, and conjectures regarding its remoter origin would at this point be premature.

Highlanders and lowlanders.The people of the various divisions of Great Acheh differ from one another, as may well be imagined, in numerous local peculiarities of language, manners, superstition, dress etc. Most of these local distinctions, when compared with the agreement in essential features are too insignificant to be noticed here. We should however note the differences between the highlanders (ureuëng tunòng), by which must be especially understood the people of the Sagi of the XXII Mukims, and the lowlanders (ureuéng barōh) who inhabit the greater part of the two remaining sagis, including the capital.

Some portions of these last two sagis have almost the same language and customs as the ureuëng tunòng, as for instance the ureuëng Buëng inhabiting the VII Mukims Buëng[42] in the Sagi of the XXVI Mukims.

Banda and dusōn.As regards language and manners the lowlanders have followed the people of the capital[43]. The Dalam or residence of the Sultan, which we incorrectly term Kraton, and which is also known as Kuta Raja or "the king's fort" (a name which we improperly apply to the whole capital) formed before our war with Acheh the nucleus of a number of fine and prosperous gampōngs. The centre of these with its mosque and market-place was called Banda Acheh i. e. the capital or trading mart of Acheh, and gave the tone to the whole country in matters of custom, dress etc. The most important of these gampōngs were Gampōng Jawa, Pandé, Peunayōng, Lam Bhuʾ, Luëng Bata, Lam Seupeuëng, Ateuëng, Batòh and Meuraʾsa. The inhabitants of these and the neighbouring villages together with their language and customs were distinguished by the epithet banda, that is, town-bred or civilized, and the people of other districts who conformed as much as possible to the tone of the capital enjoyed the same title. In contrast with these, all others who spoke in their own local dialects and were unacquainted with the manners of the town, were called dusōn (like dusun in Sundanese) i. e. countrified, uncivilized. From their position the lowlanders in general came most closely into contact with the influence of the trading centre, whilst ureuéng dusōn and ureuëng Tunòng became practically synonymous; but with this distinction, that families of standing in the Tunòng conformed as far as possible to the manners of the capital, whilst in the more distant of the lowland districts the influence of the Banda Acheh is scarcely traceable.

§ 3. Dress, Food, Luxuries, Dwellings and Household equipment.

Clothing.In dress and deportment to begin with, there is a difference between the true Tunòng folk and those of the lowland districts[44].

The peculiar Achehnese trousers (silueuë or lueuë Achèh) of prodigious width are characteristic of both, and both alike regard the fullness in the fork of this garment as an indication of Mohammedan dress in contradistinction with the tight forks of the trousers of infidels. Those worn by the lowlanders on the other hand are longer, and the materials most in use differ from those employed in the Tunòng. The loin-cloth (ija pinggang) is similarly in the eyes of both a shibboleth of Islam, as it is only infidels that feel no shame in exhibiting themselves in close-fitting trousers without further covering of the space between navel and knee. But while the Tunòng man lets his loincloth hang down to below the knees with a flap in the centre, with the lowlander it barely extends to just above the knees and its lower edge is aslant.

The lowlanders usually wear bajus or jackets (bajèë), either the bajèë Achèh[45] with long narrow sleeves and a big gold button (dōʾma) in the middle, or the bajèë ᶜèt sapay (short-sleeved baju) the dōʾma of which is at the neck. The highlanders make comparatively little use of this garment and wear in its place simply a kerchief (ija) thrown over the shoulder or fastened round the middle or else laid on the head. The head, however, is not always covered, for the Achehnese carry loads almost exclusively thereon, which method of transport they call seuʾōn.

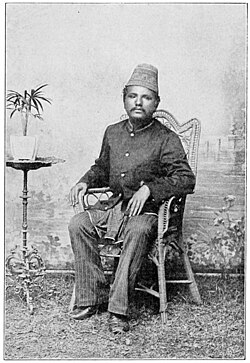

GROUP OF MEN FROM THE XXV MUKIMS.

The usual form of headgear is the kupiah[46], which greatly resembles the Mekka cap in colour. The body of the cap, which is cylindrical in shape, is made of close-pressed tree-cotton divided into narrow vertical ribs by stitching on the lining. On this thin strips of silk or cotton stuffs of various colours are worked together in such a manner as to give the impression when seen from a distance of a piece of coarse European worsted-work. Between these ribs is often fastened gold thread spreading at the top into ornamental designs. The centre of the crown is adorned with a prettily-shaped knot of gold or silver thread. In contradistinction to the Mekka cap, which is much lower in the crown, the Achehnese call theirs kupiah meukeutōb; a kerchief is sometimes wound round its lower edge as turban (tangkuloʾ), but it is just as often left uncovered. The highlander draws his long hair into a knot on the top of his head, and covers it with his cap, while the lowlander, if he do not shave his head from pious motives, lets his hair hang down loose on his neck from beneath it. In the lowland districts, too, the single headcloth or tangkuloʾ is more worn than in the Tunòng, and as in Java the origin of the wearer may be inferred from the manner of folding it. The prevailing fashion in such matters is however very liable to change. During my stay in Acheh a new method of wearing the headcloth was in vogue amongst the younger men. It was carried forward in the form of a cornucopia, a fashion said to have been set by the young pretender to the sultanate.

The reunchōng or rinchōng, a dagger with one sharp edge, and the bungkōih ranub or folded kerchief are alike indispensable to the Achehnese when he walks abroad. In the latter are placed all requisites for betel-leaf chewing, in ornamental and often costly little boxes or cases. Its four corners are held together by gold or copper bòh ru[47], and it also forms the receptacle of sundry pretty little toilet requisites, keys etc.

Persons of position or those who are going on a journey carry in addition the Achehnese sword (sikin panyang) which is the ordinary weapon used in fighting. It is of uniform width from end to end, and is placed in a sheath. The gliwang (klewang) which is carried for show by the followers of chiefs, or taken on expeditions to market or nightly walks in the gampōng, is worn without a sheath.

The Tunòng folk take with them on a journey in addition to the above, two javelins (kapfaʾ) and a spear (tumbaʾ), as well as a firearm of some description[48].

The dress of the women, while in the main identical in the Tunòng and Barōh, presents one or two points of difference. In both districts they wear over the Achehnese trousers an ija pinggang, but in the

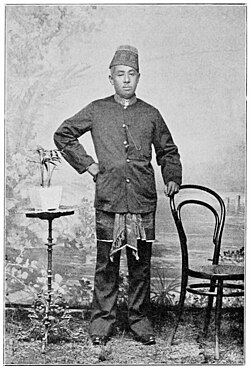

PEOPLE FROM THE XXVI MUKIMS.

lowlands this hangs down to the feet, while in the highland districts it comes hardly lower than that of the men. Women in general wear a bajèë, but its sleeves are comparatively narrower in the Tunòng, and the edging (keureuyay) at neck and sleeves is more ornamental in the lowlands. A cloth (ija sawaʾ) is thrown over the shoulders in the same way as the Javanese slendang or scarf. The women of the lowlands use another cloth (ija tōb ulèë) of the same description to cover the head when going out of doors. Locks of hair (kundè) are generally worn hanging in front of both ears. The chignon (sanggōy) is among the lowland women placed on the centre of the crown, and divided into two portions suggesting a pair of horns[49], while the Tunòng women either carry the topknot entirely to one side, or let it hang down behind in the form of a sausage[50].

The remaining articles of personal adornment exhibit few differences. Girls and women who have not yet had more than one child, wear

MAN FROM THE XXII MUKIMS WITH HIS WIFE.

armlets and anklets (gleuëng jaròë and gaki) made of suasa, which are forged on to their limbs; also chain bracelets of silver or suasa on their arms (talòë jaròë). On their necks they have metal collars, the separate portions of which closely resemble the almost circular bòh ru on the four corners of the betel-leaf kerchief, and necklaces hanging down over the breast (srapi) composed of small diamond-shaped gold plates. In their ears they wear large subangs (earrings) of gold or of buffalo-horn with a little piece of gold in the centre, by the weight of which the holes pierced in the ears are gradually widened to the greatest possible extent. Round the waist, either next the skin or over the ija pinggang they wear a chain formed of several layers (talòë kiʾiëng) fastened in front with a handsome clasp (peundéng)[51]; and on their fingers a number of rings (eunchiën or nchiën).

Food.In the remaining material necessaries of life also, the chief distinction between the Tunòng and the Barōh lies in the fact that the highlanders are more frugal and simple in their requirements. We need not here go into exact details. The staple form of food, eaten twice a day at 8–9 a.m. and at 5–6 p.m., is rice (bu) well cooked in water. With the rice is taken gulè (the sayur of the Malays), of which there are three kinds in common use; 1°. gulè masam keuʾeuëng (half-sour, half-pungent gulè) consisting of leaves or fruits[52] boiled in water mixed with onions, pepper, chilis (champli), salt, broken rice and as sour constituents bòh slimèng (blimbing) or sunti; 2°. gulè leumaʾ (rich gulè, from the cocoanut milk used in preparing it). With this is mixed a larger quantity of fragrant herbs, (such as halia or ginger and sreuë); its basis is either dried fish[53] (eungkōt thō) or karéng (small fish of the kinds biléh or awō, also dried), or the stockfish imported from the Maldives (keumamaïh) or sliced plantains or brinjals. The sour elements are the same as in 1°, above. Teumeuruy leaves are also frequently mixed with it, and cocoanut milk (santan) is an indispensable ingredient. 3°. Gulè pi u (gulè of decayed cocoanut). In this the sour elements and herbs are the same as in the other kinds, but an important additional ingredient is rotten cocoanut, from which the oil has been expressed; also some unripe nangka or jackfruit (bòh panaïh), unripe plantain, dry fish and karéng.

Besides rice and vegetables a principal article of food with the Achehnese is the stockfish (keumamaïh) imported in large quantities from the Maldives. This is prepared in two different ways; 1°. Keumamaïh cheunichah;[54] the keumamaïh is cut up into small pieces and with these are mixed ripe slimèng (blimbing)[55] pounded fine, chilis, onions and sreuë (sěrai)[56]; 2°. keumamaih reundang or tumèh, the ingredients of which differ little from those just described, but which is not eaten raw but fried in oil.

A fourth article of food, which is greatly relished by the Achehnese is boiled fresh fish from the sea or the rivers (eungkōt teunaguën). To this is added a considerable quantity of the juice of various sorts of limes (e. g. bòh munteuë, kruët, kuyuën, makén and sréng), with chilis and various savoury herbs. The whole is set on the fire in a pot with water, and not taken off until the water boils.

At kanduris (religious feasts) and suchlike occasions glutinous rice (bu kunyèt) coloured yellow with turmeric is a favourite dish. To this are always added either tumpòë (a sort of pancakes, six or seven of which are laid on top of the rice) and cheuneuruët, a gelatinous network formed of the same kind of rice, or else grated cocoanut mixed with red sugar (u mirah), or long strips of stockfish boiled in cocoanut milk, called keumamaih teunaguën.

At weddings, funeral feasts, receptions of distinguished guests and other ceremonious occasions, it is customary to serve up the rice and its accessories[57] in a definite traditional manner on dalōngs or trays. This manner of service is called meuʾidang, and we shall have occasion to notice it more fully later on. An adjunct of every idang, after the rice, fish and gulé, is the tray of sweetmeats, containing a dish of glutinous rice (bu leukat), this time without turmeric, and a dish of pisang peungat—ripe plantains sliced thin and boiled with cloves, cinnamon, sugar and some pandan-leaves. To these is often added sròykaya—eggs with cocoanut milk and herbs well cooked by steaming.

Fruits (bòh kayèë) are constantly eaten, but do not form the special accessories of any feast. After a funeral those who are present at the burial ground eat plantains and such other fruits as are for sale in the market.

Sweetmeats are called peunajōh (which properly means simply „victuals”), and are as in Java very various in form and name[58], though they differ but little in actual ingredients. The constituents of these are almost always grated cocoanut or cocoanut milk, glutinous rice or flour made therefrom, sugar and certain herbs, eggs and oil. They are eaten at odd times and are only set before guests when (as for example at recitations of the Qurān) they are assembled for hours together, so that a single great meal is insufficient to while away the time. On such occasions tea and coffee are also served, though the use of these beverages is generally restricted to invalids.

Small kanduris or religious feasts are of very common occurrence. At these yellow glutinous rice forms the pièce de resistance, though a goat is sometimes slaughtered for the guests. Otherwise buffaloes, oxen, goats and sheep are seldom killed except at the great annual festivals or in fulfilment of a vow.

Luxuries. The use of the betel-leaf (ranub) with its accessories (pineung, gapu, gambé[59], bakōng and sundry odoriferous herbs) is absolutely universal. Many both in the highland and lowland districts make an intemperate use of opium, but to nothing like the same extent as in the colonies of pepper-planters on the East and West Coasts, where all the vices of the Achehnese reach their culminating point. The prepared opium or chandu is smoked (piëb) from the ordinary opium-pipes (gò chandu) with the aid of little lamps called panyòt. In the days of Habib Abdurrahman and similar religious zealots, the smoking went on only indoors and by stealth. The opium-sheds (jambō chandu) which certain persons in the more distant plantations had built in order to enjoy this luxury in company, were burnt down by that sayyid.

On the West Coast especially, the practice of smoking opium in company still prevailed, and was marked by some characteristic customs. The votaries of the habit sit together in a prescribed position, and the pipe passes round. Each must in his turn take two pulls so strong as to extinguish the lamp; he then hands the pipe to his right-hand neighbour with a seumbah or respectful salute. The opium used in such assemblages is mixed with tobacco or other leaves and is called madat[60]. The Achehnese (of course wrongly) try to associate this word with adat, and assert that it means "the smoking of opium in conformity with certain adat or customs". In Great-Acheh, however, such public opium-smoking has always been exceptional. Every opium-smoker, be he small or great, is sure to be known as such, yet he prefers to perpetrate the actual deed in the solitude of his inner chamber.

Some Achehnese smoke opium in order, as they assert, to prolong the pleasure of coition.

The use of strong drink, which usually degenerates into excess, is especially to be met with among the lowlanders, but is restricted to the upper classes or those who come much into contact with Europeans. For the ordinary Achehnese water is almost his only drink; occasionally he takes some sugarcane juice, squeezed out of the cane by means of a very primitive press. Hence it comes that ngòn blòë ië teubèë "to buy sugarcane juice" is the ordinary name for a douceur.

It was an honoured tradition in Acheh that a member of the Sultan's family who had the reputation of being even a moderate opium-smoker should be excluded from the succession. Intoxicating liquors on the other hand were, as is well known, always to be found in the Dalam. I learned from a widow of Sultan Ibrahim Mansur Shah[61], (1858–70) that the latter had once murdered his own child in a fit of drunken frenzy[62].

The Achehnese colonists on the East and West Coasts who live there sometimes for years at a time in a society where there are no women, develop every vice of the nation to its highest pitch. The true highlanders are reputed not indeed more virtuous (for with them theft and robbery are the order of the day) but less weak and effeminate than the lowlanders. Among them opium, drink and unnatural crime exercise less influence than in the coast provinces. Unreasoning fanaticism, contempt for all strangers and self conceit are all more strongly marked in the upper country than in the lowland districts, which have grown somewhat "civilized" through contact with foreigners. The highlanders esteem themselves (and the lowlanders do not deny it)

GROUP OF MEN FROM THE XXII MUKIMS.

braver men than their brethren of the two remaining "angles" (sagòë) of the country. A hero is in common speech as well as in literature, often spoken of as aneuʾ tunòng kruëng= "a son of the upper reaches of the river."

The house and its equipment.In the arrangement of their dwellings there is but little difference between Tunòng and Barōh. The plate and explanation given at the end of this volume show clearly the principal features of the Achehnese dwelling-house[63]. It must be remembered that these houses are posed of either three or (as in the plate) five rueuëngs or divisions between the main rafters. In the first case the number of pillars supporting the main body of the house is 16, in the second 24. To form an idea of a house of three rueuëngs it is only necessary to cut off from that depicted in the plate all that lies to one side or the other of the central passage (rambat).

It has further to be noted that the back verandah (sramòë likōt) sometimes also serves as kitchen, and in that case the extension of the house for this purpose as shown in our plate is omitted. The gable-ends always face East and West, so that the main door and the steps leading up to it must have a northerly or southerly aspect.

Further additions are often made to the house on its East or West side, when the family is enlarged by the marriage of a daughter. These are as regards their floor-level (aleuë) tached on as annexes to the back verandah. Some new posts are set up along the side of the verandah to support an auxiliary roof, the inner edge of which projects from the edge of the main roof. Parents who are not wealthy enough to build for their daughters a separate house close by, retire, as far as their private life is concerned, into the temporary building we have just described (anjōng)[64] and leave the inside room (jurèë) to the young married couple.

We shall now make a survey of the Achehnese house and its belongings, not with the object of giving a full description of its subordinate parts (which may be found in the plate), or a complete inventory of all its equipment, but to show the part played by the various portions of the house in the lives of its inmates[65].

Round about each dwelling is a court-yard, generally supplied with the necessary fruit-trees etc. and sometimes cultivated so as to deserve the name of a garden (lampōïh). Regular gardens, in which are planted sugarcane, betelnuts, cocoanuts etc., are sometimes to be found in this enclosure, sometimes in other parts of the gampōng. The courtyard is surrounded by a strong fence (pageuë) through which a door leads out on to the narrow gampōng-path (jurōng); this in its turn leads through the gampōng to the main road[66] (rèt), which runs through rice-fields, gardens and uncultivated spaces, and unites one gampōng with another. The whole gampōng, like each courtyard, is surrounded with a fence.

A good fence is generally formed of two rows of glundōng or keudundōng trees or the like, set at a uniform distance apart, leaving a slight intervening space which is filled with triëng or thorny bamboo. The two rows are united firmly together by bamboos fastened horizontally from tree to tree as crosspieces. There are usually from three to five of these cross bamboos in the length of the fence.

Sometimes trees or bushes of other sorts which are themselves furnished with thorns, such as the daréh, are employed to fence in gardens, courtyards or gampōngs.

In many courtyards[67], as appears from what we have said above, more than a single dwelling house is to be found. As a rule each additional house is the habitation of one of the married daughters of the same family or in any case belongs to women descended from the same ancestress.

An indispensable item is the well (mòn), from which the women draw water for household use in buckets (tima) made of the spathe of the betel-palm (seutuë)ʾ, where they wash their clothes and utensils, bathe (so far as the uncleanly Achehnese deem it necessary to do so) and perform other needs. A gutter (salōran) carries off the water etc. to an earthenware conduit, which conducts both water and dung to a manure-heap (adén or jeuʾa) which is always very wet. Into this also falls by means of another gutter all the wet refuse that is thrown out from the back part of the house and kitchen. A screen (pupalang) shuts off those who are using the well from the gaze of the passers-by.

The space underneath the house (yub mòh or yub rumòh) serves as the receptacle of various articles. The jeungki or see-saw rice-pounder for husking rice; the keupōʾ[68], a space between four or six posts, separated off by a partition of plaited cocoanut leaves (bleuët) or similar material thrown round the posts, and in which the newly harvested rice is kept till threshed, and the threshing itself takes place; the krōngs, great tun-shaped barrels made of the bark of trees or plaited bamboo or rattan, wherein is kept the unhusked rice after threshing, which barrels are also sometimes placed in separate open buildings outside the house; the press (peuneurah) for extracting the oil[69] from decayed cocoanuts (piʾ u), and a bamboo or wooden rack (prataïh or panteuë) on which lies the firewood cleft by the women; these are the principal inanimate objects to be met with in the yub mòh.

Should the space beneath the house happen to be flooded in the rainy season, the store of rice is of course removed indoors.

Dogs, goats, sheep, ducks and fowls are also housed in the yub mòh. The brooding hens are kept under a cage-shaped seureukab[70], the others at night in a sriweuën or eumpung (fowl-run), while the fighting-cocks are in the daytime fastened up here by strings to the posts, though at night these favourite animals are brought into the front verandah[71].

Cows and buffaloes are housed in separate stalls or weuë, while ponies are tied up here and there to trees. The Achehnese however seldom possess the latter animals; those who have them use them but little and treat them with scant care[72].

All the small live stock huddled together in the yub mòh naturally render the place somewhat the reverse of wholesome. To this it must be added that much of the refuse from the house is simply thrown in there instead of being conveyed to the dung-heap by the gutter above referred to. Most contributions of this sort come through the guha[73], a hole pierced in the floor of the back verandah to receive odds and ends of refuse wet and dry, but which also serves as a latrine for children and invalids! Besides this, the floor of every inner room (jurèë) is furnished with a long open fissure over which the dead are laid to be washed, so as to let the water used in the ablution flow off easily.

Notwithstanding all this, the yub mòh is also used as a temporary resting-place for human beings. If there are children in the house, a large swinging cradle is hung here for their use. Here too the women set up their cloth on the loom and perform other household duties, for which purpose a certain portion is partitioned off by a screen (pupalang). At festivals some of the guests are entertained in the same place; and here it is customary to receive visits of condolence for a death. Some chiefs keep imprisoned in the yub mòh those who refuse to pay the fines imposed on them.

At the foot of the steps leading up to the house (gaki reunyeun) there always stands a great earthenware water-jar (guchi). Close to this is a hooked stick planted in the ground to hold a bucket (seuneulat tima) and a number of stones rather neatly arranged. Anyone who wishes to enter the house places his dusty or muddy feet on these stones and pours water over them from the bucket till they are clean.

Where there is a separate kitchen (rumòh dapu), a flight of steps leading down from this allows the inmates to quit the house from the back, but as a rule the steps in front are the only means of egress, so that the women must traverse the front verandah every time they go out of doors.

Some houses have a wooden platform surrounding the foot of the steps and protected by the penthouse roof which covers the latter. It is set against the side of the house and stands a little lower than the floor of the front verandah. This serves the inmates as an occasional place to sit and laze in and also for the pursuit of parasites in one another's hair, a practice as necessary and popular among the Achehnese as among the Javanese[74]. Here too the little children play.

By the house door access is gained to the front verandah or as the Achehnese call it, the stair verandah (sramòë reunyeun), which is separated from the rest of the house by a partition in which are the doors of the inner chambers (jurèë) and the aperture leading into the central passage, filled generally either by a curtain or a door.

This is the portion of the Achehnese dwelling to which the uninitiated are admitted. Here guests are received, kanduris or religious feasts are given and business discussed. Part of the floor (aleuë) is covered with matting; on ceremonial occasions carpets (plumadani or peureumadani) are spread over this, and on top of these again each guest finds an ornamentally worked square sitting-mat (tika duëʾ) placed ready for him. A sort of bench made of wood or bamboo called prataïh sometimes serves the master of the house as a bedstead during part of the night, when he finds the heat excessive within. Here too are to be found a number of objects which betray the calling or favourite sport of their owner, some on shelves or bamboo racks (sandéng) against the wall, some stuck in the crevices of the wall itself. There the fisherman hangs his nets (jeuë or nyaréng), the huntsman his snares (taròn), all alike their weapons; there too are kept certain kinds of birds such as the leuëʾ (Mal. těkukur, a kind of small dove), which are much used for fighting-matches.

The passage (rambat) is at one side in a house of three sections, but in one of five it is right in the middle between the two bedrooms. It is entered by none but women, members of the household or the family, or men on very intimate terms of acquaintanceship, as it only gives access to the back verandah, the usual abode of the women, who there perform their daily household tasks.

Some provisions are stored in the rambat, as for instance a guchi or earthenware jar of decayed cocoanut (pi u) for making oil, and a jar of vinegar made from the juice of the arèn (ië jōʾ) or the nipah. Here too stands the tayeuën, a smaller portable earthenware jar in which the mistress of the house or her maidservant fetches water from the well to fill the guchi which stands in the back verandah and contains the supply of water for household use.

Some short posts (rang) extending only from the roof to the floor are furnished with small pieces of plank on which are hung the brass plates with stands of the same metal on which food is served to guests, the trays (dalōng) big enough to hold an idang for four or five persons and the smaller ones (krikay) on which are dished the special viands for the most distinguished visitors. Either in the rambat or the sramòë likōt stands a chest (peutòë) containing the requisite china and earthenware.

Porcelain dishes (pingan) and plates or small dishes (chipé) are to be found in these chests almost everywhere in the lowland districts, but when there are no guests the simpler ware common in the Tunòng is here also used, viz. large earthenware or wooden plates called chapah and smaller ones known as chuèʾ.

The back verandah serves as it were as a sitting-room and as we have seen often answers the purpose of a kitchen as well. It contains a sitting mattress (tilam duëʾ) with a mat on it especially intended for the use of the master, when he comes here to eat his meals or to repose; while a low bench (prataïh) similarly covered with a mat serves as a resting-place for small children. Here are to be found, on shelves or racks fixed against the wall, plates, earthen cooking-pots (blangòng), circular earthen or brass saucepans (kanèt)[75] in which rice is boiled[76], earthen frying-pans with handles (sudu) for frying fish ete., the curry-stone (batèë neupéh) for grinding spices etc., with the grater (aneuʾ) that appertains to it, and earthenware or brass lamps (panyòt) in the form of round dishes with four or seven mouths (mata) in each of which a wick is placed. Some of these lamps are suspended by cords from above (panyòt gantung), others rest on a stand (panyòt dòng). From the rafters and beams hang at intervals little nets called salang, neatly plaited of rattan, for holding dishes which contain food, so as to protect their contents to some extent from the attacks of various domestic animals.

Drinking vessels of brass (mundam) or earthenware (peunuman) are to be found in all the different apartments. They have as covers brass drinking-cups which are inverted and replaced after use.

Cooking is performed in a very simple manner. Five stones arranged almost exactly in this form ⁙ constitute two teunungèës[77] or primitive chafing-dishes in which wood fires are lit, one for the rice and the other for the vegetables (gulè). The use of iron chafing-dishes (kran) on three legs is a mark of a certain degree of luxury.

The holy of holies in the house is the one part of it that may be really called a room, the jurèë, to which access is had by a door leading out on to the back verandah. Here the married couple sleep, here takes place the first meeting of bride and bridegroom at the mampleuë (inf. chapter III, § 1) and here the dead are washed. These rooms are seldom entered by any save the parents, children and servants.

The floor is as a rule entirely covered with matting. The roofing is hidden by a white cloth (tirè dilangèt) and the walls are in like manner covered with tirè or hangings. Round the topmost edge of the tirè runs a border formed of diamond-shaped pieces of cloth of various colours; these when stitched together form the pattern called in Acheh chradi or mirahpati. Such disguising of roof and walls is resorted to in the other parts of the house only on festive occasions. On a low bench or platform (prataïh) is placed a mattress (tilam éh) with a mat over it, and this couch is usually surrounded with a mosquitonet (kleumbu).

Besides this there is spread on the floor a sitting-mattress (tilam duèʾ) of considerable size, but intended only for the man's use, and thus provided with a sitting mat. On both mattresses are piles of cushions (bantay susōn) shaped like bolsters and adorned at either end with pretty and often costly trimming. A sitting mattress has about four, a sleeping mattress as many as fifteen cushions of this description.

The clothing and personal ornaments are kept in a chest which stands in the jurèë. Well-to-do people generally have for this purpose chests the front of which is formed of two little doors opening outwards. These are called peutòë dòng or standing chests to distinguish them from the chests with covers. When the Achehnese learned to use European cupboards, they gave them the same name.

Along the small posts (rang) inside the house there is usually fastened a plank set on edge on the floor. This serves as a specious screen for all manner of untidiness, concealing all such rubbish as the inmates may choose to throw between it and the wall.