The American Cyclopædia (1879)/Nebula

NEBULA (Lat., mist, vapor), an aggregation of stars or stellar matter having the appearance, through an ordinary telescope, of a small, cloud-like patch of light. An enlargement of telescopic power usually converts this appearance into a cluster of innumerable stars, besides bringing to light other nebulæ before invisible. These in turn yield to augmented magnifying power; and thus every increase in the capacity of the telescope adds to the number of clusters resolved from nebulae, and of nebulae invisible to lower powers.

Nebulæ proper, or

those which have not been definitely resolved,

are found in nearly every quarter of the firmament,

though abounding especially near those

regions which have fewest stars. Scarcely

any are found near the milky way, and the

great mass of them lie in the two opposite

spaces furthest removed from this circle. Their

forms are very various, and often undergo

strange and unexpected changes as the power

of the telescope with which they are viewed

is increased, so as not to be recognizable in

some cases as the same objects. The spiral

nebulae are an example of this transformation.

This class was recognized by Lord Rosse

through the use of his six-foot reflector. Many

of them had been long known as nebulæ,

but their characteristic spiral form had never

been suspected. They have the appearance of

a maelstrom of stellar matter, and are among

the most interesting objects in the heavens.

|

|

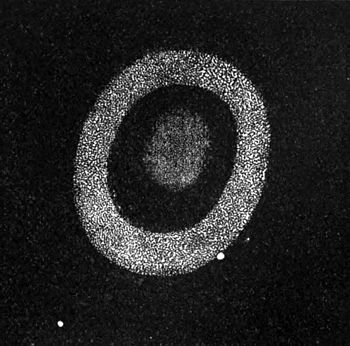

| Fig. 2. — Stellar Nebula. | Fig. 3. — Planetary Nebula. |

There is another class of nebulæ which bear

a close resemblance to planetary disks, and are

hence called planetary nebulæ. They are very

rare. Some of them present remarkable

peculiarities of color. Sir John Herschel has

described a beautiful example of this class,

situated in the southern cross. But in telescopes

of the highest power some of the so-called

planetary nebulæ assume a totally different

appearance; and many of them are singularly

complicated in structure, instead of being

simple globes of nebulous matter, as was formerly

supposed. There are several which

have perfectly the appearance of a ring, and

are called annular nebulæ. A conspicuous and

beautiful example is situated in Lyra. Some

appear to be physically connected in pairs like

double stars. Most of the small nebulæ have

the general appearance of a bright central

nucleus enveloped in a nebulous veil. This

nucleus is sometimes concentrated as a star and

sometimes diffused. The enveloping veil is

sometimes circular and sometimes elliptical,

with every degree of eccentricity between a circle

and a straight line. There are some which,

with a general disposition to symmetry of form,

have great branching arms or filaments with

more or less precision of outline. An example

of this is Lord Rosse's Crab nebula. Another

remarkable object is the nebula in Andromeda,

which is visible with the naked eye, and is

the only one which was discovered before the

invention of the telescope. Simon Marius

(1612) describes its appearance as that of a

candle shining through horn.

Besides the

above, which have comparatively regular forms,

there are others more diffused, and devoid

of symmetry of shape. A remarkable

example is the great nebula in Orion, discovered

by Huygens in 1656. This nebula and

that in Andromeda have been admirably

delineated by the professors Bond of Harvard

observatory. (See “Memoirs of the American

Academy of Arts and Sciences,” new

series, vol. iii.) The great nebula in Argo,

which Sir John Herschel has charted with

exquisite care and elaborateness in his “Cape

Observations,” is another example of this class.

In the southern firmament there are two

extensive nebulous tracts known as the

Magellanic clouds; the greater called Nubecula

Major, and occupying an area of 42 square

degrees; the smaller called Nubecula Minor,

and covering about 10 square degrees. In

these tracts are found multitudes of small

nebulæ and clusters. The number of these

wonderful objects which have been recognized

in all the heavens is upward of 5,000. Of

these fewer than 150 were known prior to the

time of Sir William Herschel. In 1786 he

communicated to the royal society a catalogue

of 1,000 new nebulæ and clusters; in 1789 a

second catalogue of the same number of new

objects; and in 1802 a third which included

500 more. In 1833 Sir John Herschel

communicated to the royal society a catalogue of

2,306 nebulæ and clusters in the northern

hemisphere observed by him, 500 of which were

new. In 1847 appeared his “Cape Observations,”

which contained catalogues of 1,708

nebulæ and clusters in the southern heavens.

—

The application of spectroscopic analysis to

these objects, by Huggins, Secchi, Vogel, and

others, has resulted in the noteworthy discovery

that while some among the nebulæ are

really clusters of stars, others consist in the

main of gaseous matter. The former give

spectra resembling in their general characteristics

the spectra of stars; the latter give a

spectrum of three bright lines (occasionally

four), one line corresponding in position to a

line in the spectrum of hydrogen, another

corresponding to a line in the spectrum of nitrogen.

The resolvable nebulæ mostly give spectra

of the former class, while the bright-line

spectrum is given by all the irregular nebulæ

hitherto examined, and by the planetary nebulæ.

Of about 70 nebulæ examined by Huggins,

nearly one third gave the spectrum indicative

of gaseity, the rest giving a stellar spectrum. —

As to the nature of nebulæ, two chief theories

have been advanced. It was first suggested by

Wright of Durham, and afterward maintained

by Kant and Lambert, that the nebulæ are

stellar galaxies similar to our own star system.

Sir W. Herschel, at the beginning of his

researches into the constitution of the universe,

adopted this view as respects certain nebulæ

which he regarded as external, while holding

(contrary to the usual statement in our text

books of astronomy) that many nebulæ form

parts of our own star system. At a later stage

of his labors he advanced the hypothesis

commonly known as Herschel's nebular hypothesis,

which however related only to certain

orders of nebulæ. At this stage Herschel for

the first time indicated his ideas respecting the

arrangement of all orders of stellar aggregations

and nebulous matter. At the lower

extremity of the scale he placed widely spread

luminosity, such as he had first described in

1802. He passed from this irregularly spread

luminosity, through all the orders of gaseous

nebulæ (irregular nebulæ, planetary nebulæ,

nebulous stars) formed by the gradual

condensation of the gaseous matter, until the star

itself is formed; then he entered on the part of

the series he had before recognized, passing on

to the various orders of stellar aggregation,

diffused clusters, ordinary stellar nebulæ, and

more and more condensed groups of stars, up

to the richest star clusters. At this period

(1814) we no longer find him speaking of

external nebulæ; not, it is to be presumed, that

he no longer recognized the probability that

other stellar galaxies besides our own exist,

but that he no longer found it possible to

discriminate those nebulæ which are external

from the far greater number which

unquestionably form component parts of our own

sidereal system. The researches of the present

writer into the subject dispose him to

believe that our sidereal system extends far

beyond the limits which have ordinarily been

assigned to it, and that there are no nebulæ

which can be regarded as external to it.